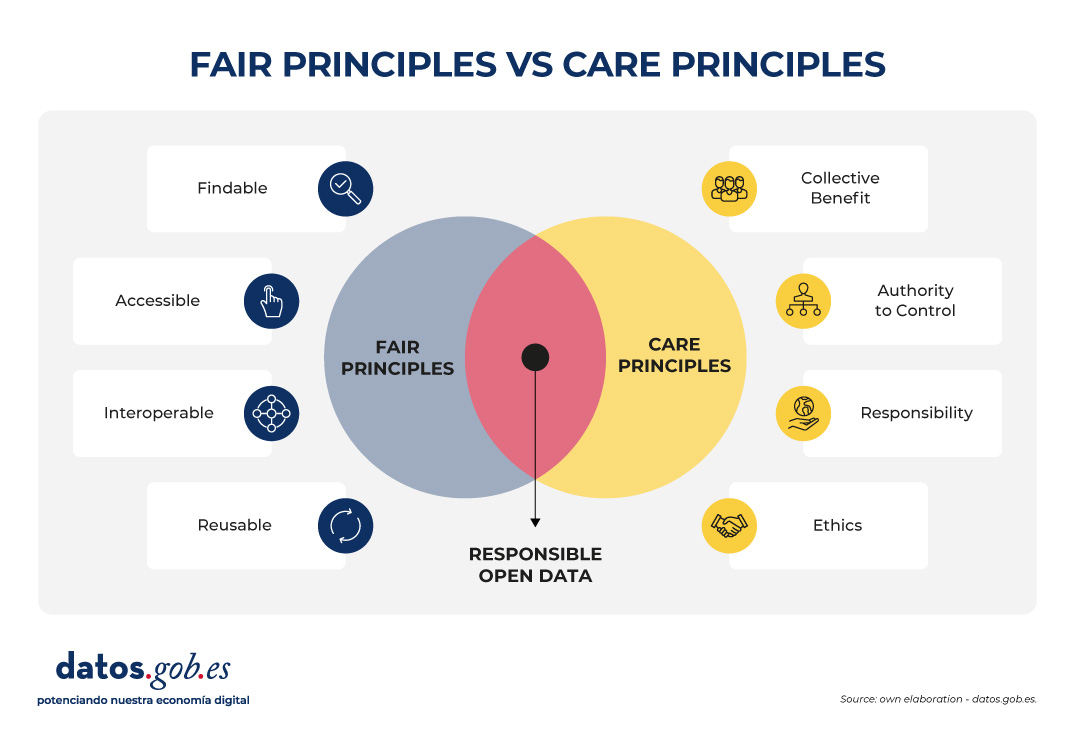

In recent years, open data initiatives have transformed the way in which both public institutions and private organizations manage and share information. The adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles has been key to ensuring that data generates a positive impact, maximizing its availability and reuse.

However, in contexts of vulnerability (such as indigenous peoples, cultural minorities or territories at risk) there is a need to incorporate an ethical framework that guarantees that the opening of data does not lead to harm or deepen inequalities. This is where the CARE principles (Collective Benefit, Authority to Control, Responsibility, Ethics), proposed by the Global Indigenous Data Alliance (GIDA), come into play, which complement and enrich the FAIR approach.

It is important to note that although CARE principles arise in the context of indigenous communities (to ensure indigenous peoples' effective sovereignty over their data and their right to generate value in accordance with their own values), these can be extrapolated to other different scenarios. In fact, these principles are very useful in any situation where data is collected in territories with some type of social, territorial, environmental or even cultural vulnerability.

This article explores how CARE principles can be integrated into open data initiatives generating social impact based on responsible use that does not harm vulnerable communities.

The CARE principles in detail

The CARE principles help ensure that open data initiatives are not limited to technical aspects, but also incorporate social, cultural and ethical considerations. Specifically, the four CARE principles are as follows:

-

Collective Benefit: data must be used to generate a benefit that is shared fairly between all parties involved. In this way, open data should support the sustainable development, social well-being and cultural strengthening of a vulnerable community, for example, by avoiding practices related to open data that only favour third parties.

-

Authority to Control: vulnerable communities have the right to decide how the data they generate is collected, managed, shared, and reused. This principle recognises data sovereignty and the need to respect one’s own governance systems, rather than imposing external criteria.

-

Responsibility: those who manage and reuse data must act responsibly towards the communities involved, recognizing possible negative impacts and implementing measures to mitigate them. This includes practices such as prior consultation, transparency in the use of data, and the creation of accountability mechanisms.

-

Ethics: the ethical dimension requires that the openness and re-use of data respects the human rights, cultural values and dignity of communities. It is not only a matter of complying with the law, but of going further, applying ethical principles through a code of ethics.

Together, these four principles provide a guide to managing open data more fairly and responsibly, respecting the sovereignty and interests of the communities to which that data relates.

CARE and FAIR: complementary principles for open data that transcend

The CARE and FAIR principles are not opposite, but operate on different and complementary levels:

-

FAIR focuses on making data consumption technically easier.

-

CARE introduces the social and ethical dimension (including cultural considerations of specific vulnerable communities).

The FAIR principles focus on the technical and operational dimensions of data. In other words, data that comply with these principles are easily locatable, available without unnecessary barriers and with unique identifiers, use standards to ensure interoperability, and can be used in different contexts for purposes other than those originally intended.

However, the FAIR principles do not directly address issues of social justice, sovereignty or ethics. In particular, these principles do not contemplate that data may represent knowledge, resources or identities of communities that have historically suffered exclusion or exploitation or of communities related to territories with unique environmental, social or cultural values. To do this, the CARE principles, which complement the FAIR principles, can be used, adding an ethical and community governance foundation to any open data initiative.

In this way, an open data strategy that aspires to be socially just and sustainable must articulate both principles. FAIR without CARE risks making collective rights invisible by promoting unethical data reuse. On the other hand, CARE without FAIR can limit the potential for interoperability and reuse, making the data useless to generate a positive benefit in a vulnerable community or territory.

An illustrative example is found in the management of data on biodiversity in a protected natural area. While the FAIR principles ensure that data can be integrated with various tools to be widely reused (e.g., in scientific research), the CARE principles remind us that data on species and the territories in which they live can have direct implications for communities who live in (or near) that protected natural area. For example, making public the exact points where endangered species are found in a protected natural area could facilitate their illegal exploitation rather than their conservation, which requires careful definition of how, when and under what conditions this data is shared.

Let's now see how in this example the CARE principles could be met:

-

First, biodiversity data should be used to protect ecosystems and strengthen local communities, generating benefits in the form of conservation, sustainable tourism or environmental education, rather than favoring isolated private interests (i.e., collective benefit principle).

-

Second, communities living near or dependent on the protected natural area have the right to decide how sensitive data is managed, for example, by requiring that the location of certain species not be published openly or published in an aggregated manner (i.e., principle of authority).

-

On the other hand, the people in charge of the management of these protected areas of the park must act responsibly, establishing protocols to avoid collateral damage (such as poaching) and ensuring that the data is used in a way that is consistent with conservation objectives (i.e. the principle of responsibility).

-

Finally, the openness of this data must be guided by ethical principles, prioritizing the protection of biodiversity and the rights of local communities over economic (or even academic) interests that may put ecosystems or the populations that depend on them at risk (principle of ethics).

Notably, several international initiatives, such as Indigenous Environmental Data Justice related to the International Indigenous Data Sovereignty Movement and the Research Data Alliance (RDA) through the Care Principles for Indigenous Data Governance, are already promoting the joint adoption of CARE and FAIR as the foundation for more equitable data initiatives.

Conclusions

Ensuring the FAIR principles is essential for open data to generate value through its reuse. However, open data initiatives must be accompanied by a firm commitment to social justice, the sovereignty of vulnerable communities, and ethics. Only the integration of the CARE principles together with the FAIR will make it possible to promote truly fair, equitable, inclusive and responsible open data practices.

Jose Norberto Mazón, Professor of Computer Languages and Systems at the University of Alicante. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.