Open data portals are experiencing a significant growth in the number of datasets being published in the transport and mobility category. For example, the EU's open data portal already has almost 48,000 datasets in the transport category or Spain's own portal datos.gob.es, which has around 2,000 datasets if we include those in the public sector category. One of the main reasons for the growth in the publication of transport-related data is the existence of three directives that aim to maximise the re-use of datasets in the area. The PSI directive on the re-use of public sector information in combination with the INSPIRE directive on spatial information infrastructure and the ITS directive on the implementation of intelligent transport systems, together with other legislative developments, make it increasingly difficult to justify keeping transport and mobility data closed.

In this sense, in Spain, Law 37/2007, as amended in November 2021, adds the obligation to publish open data to commercial companies belonging to the institutional public sector that act as airlines. This goes a step further than the more frequent obligations with regard to data on public passenger transport services by rail and road.

In addition, open data is at the heart of smart, connected and environmentally friendly mobility strategies, both in the case of the Spanish "es.movilidad" strategy and in the case of the sustainable mobility strategy proposed by the European Commission. In both cases, open data has been introduced as one of the key innovation vectors in the digital transformation of the sector to contribute to the achievement of the objectives of improving the quality of life of citizens and protecting the environment.

However, much less is said about the importance and necessity of open data during the research phase, which then leads to the innovations we all enjoy. And without this stage in which researchers work to acquire a better understanding of the functioning of the transport and mobility dynamics of which we are all a part, and in which open data plays a fundamental role, it would not be possible to obtain relevant innovations or well-informed public policies. In this sense, we are going to review two very relevant initiatives in which coordinated multi-national efforts are being made in the field of mobility and transport research.

The information and monitoring system for transport research and innovation

At the European level, the EU also strongly supports research and innovation in transport, aware that it needs to adapt to global realities such as climate change and digitalisation. The Strategic Transport Research and Innovation Agenda (STRIA) describes what the EU is doing to accelerate the research and innovation needed to radically change transport by supporting priorities such as electrification, connected and automated transport or smart mobility.

In this sense, the Transport Research and Innovation Monitoring and Information System (TRIMIS) is the tool maintained by the European Commission to provide open access information on research and innovation (R&I) in transport and was launched with the mission to support the formulation of public policies in the field of transport and mobility.

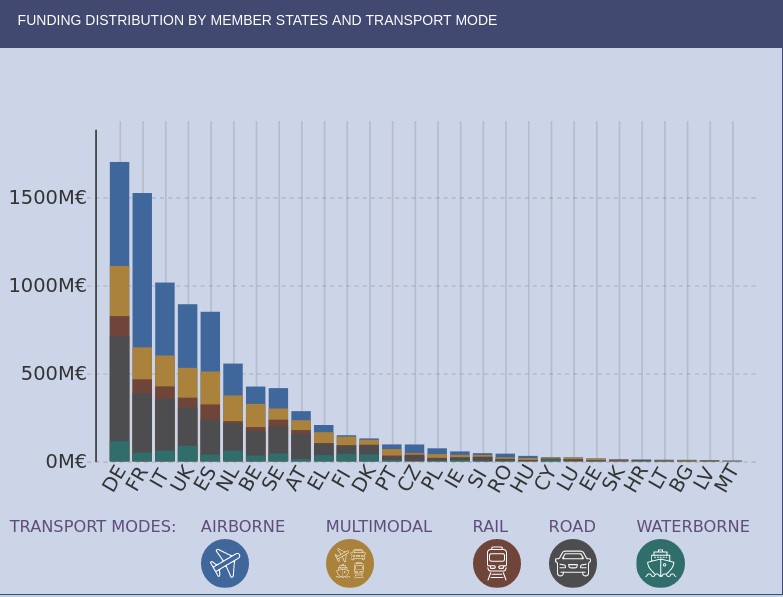

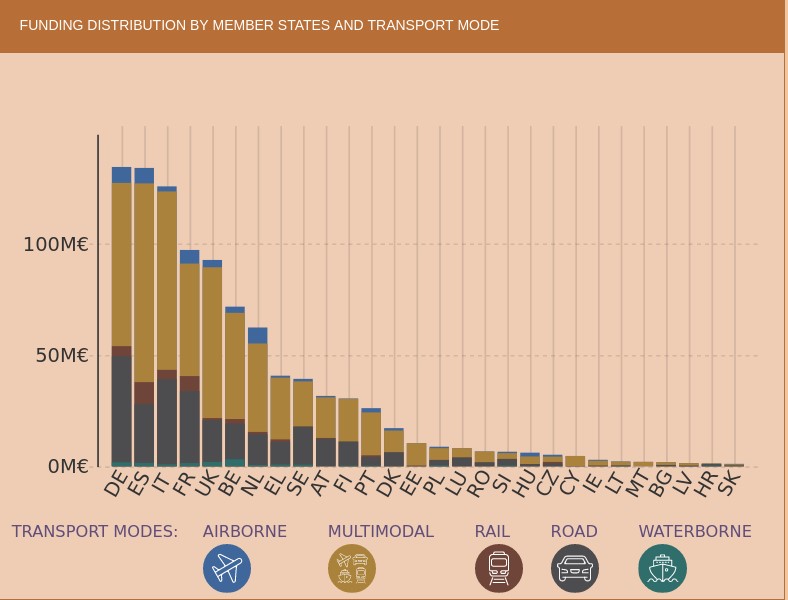

TRIMIS maintains an up-to-date dashboard to visualise data on transport research and innovation and provides an overview and detailed data on the funding and organisations involved in this research. The information can be filtered by the seven STRIA priorities and also includes data on the innovation capacity of the transport sector.

If we look at the geographical distribution of research funds provided by TRIMIS, we see that Spain appears in fifth place, far behind Germany and France. The transport systems in which the greatest effort is being made are road and air transport, beneficiaries of more than half of the total effort.

However, we find that in the strategic area of Smart Mobility and Services (SMO), which are evaluated in terms of their contribution to the overall sustainability of the energy and transport system, Spain is leading the research effort at the same level as Germany. It should also be noted that the effort being made in Spain in terms of multimodal transport is higher than in other countries.

As an example of the research effort being carried out in Spain, we have the pilot dataset to implement semantic capabilities on traffic incident information related to safety on the Spanish state road network, except for the Basque Country and Catalonia, which is published by the General Directorate of Traffic and which uses an ontology to represent traffic incidents developed by the University of Valencia.

The area of intelligent mobility systems and services aims to contribute to the decarbonisation of the European transport sector and its main priorities include the development of systems that connect urban and rural mobility services and promote modal shift, sustainable land use, travel demand sufficiency and active and light travel modes; the development of mobility data management solutions and public digital infrastructure with fair access or the implementation of intermodality, interoperability and sectoral coupling.

The 100 mobility questions initiative

The 100 Questions Initiative, launched by The Govlab in collaboration with Schmidt Futures, aims to identify the world's 100 most important questions in a number of domains critical to the future of humanity, such as gender, migration or air quality.

One of these domains is dedicated precisely to transport and urban mobility and aims to identify questions where data and data science have great potential to provide answers that will help drive major advances in knowledge and innovation on the most important public dilemmas and the most serious problems that need to be solved.

In accordance with the methodology used, the initiative completed the fourth stage on 28 July, in which the general public voted to decide on the final 10 questions to be addressed. The initial 48 questions were proposed by a group of mobility experts and data scientists and are designed to be data-driven and planned to have a transformative impact on urban mobility policies if they can be solved.

In the next stage, the GovLab working group will identify which datasets could provide answers to the selected questions, some as complex as "where do commuters want to go but really can't and what are the reasons why they can't reach their destination easily?" or "how can we incentivise people to make trips by sustainable modes, such as walking, cycling and/or public transport, rather than personal motor vehicles?"

Other questions relate to the difficulties encountered by reusers and have been frequently highlighted in research articles such as "Open Transport Data for maximising reuse in multimodal route": "How can transport/mobility data collected with devices such as smartphones be shared and made available to researchers, urban planners and policy makers?"

In some cases it is foreseeable that the datasets needed to answer the questions may not be available or may belong to private companies, so an attempt will also be made to define what new datasets should be generated to help fill the gaps identified. The ultimate goal is to provide a clear definition of the data requirements to answer the questions and to facilitate the formation of data collaborations that will contribute to progress towards these answers.

Ultimately, changes in the way we use transport and lifestyles, such as the use of smartphones, mobile web applications and social media, together with the trend towards renting rather than owning a particular mode of transport, have opened up new avenues towards sustainable mobility and enormous possibilities in the analysis and research of the data captured by these applications.

Global initiatives to coordinate research efforts are therefore essential as cities need solid knowledge bases to draw on for effective policy decisions on urban development, clean transport, equal access to economic opportunities and quality of life in urban centres. We must not forget that all this knowledge is also key to proper prioritisation so that we can make the best use of the scarce public resources that are usually available to meet the challenges.

Content written by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Current approaches to public policy-making that respond quickly to changing trends in technology are too often unsuccessful. Policy makers are often pressured to develop and adopt laws or guidelines without the evidence needed to do so safely and without the opportunity to consult affected experts and users - meaning that they will not be designed with the needs of those who will be directly affected by them later in life in mind.

This problem is particularly acute in the case of emerging technologies, where, in addition, some companies often actively resist regulation by using their own lobbying, or simply by occupying the regulatory vacuum by setting de facto standards through their own practices.

For all these reasons, policymakers are beginning to adopt some alternative approaches to public policymaking in the technological environment. Among these alternatives is the rise of laboratories of innovation on public policy, whose main objective is to offer a tool that facilitates the agile creation of such policies by ensuring that they are oriented towards the public interest while at the same time enabling innovation and the development of enterprises.

What is a public policy laboratory?

A Policy Lab is a space where different stakeholders are invited to work together, each contributing their particular skills to find solutions to common problems. This is done through an open and iterative process in which possible solutions are experimented with, while maintaining a permanent focus on the needs and expectations of the individuals concerned. The work of these laboratories is based on evidence to address issues that are of particular social relevance, often in very dynamic and growing areas such as technology, climate change or finance.

Policy labs are therefore becoming increasingly popular mechanisms for building bridges between experts, public administration and society in order to solve outstanding challenges while taking advantage of the opportunities offered by emerging areas of knowledge. Such laboratories have been flourishing profusely lately, both in Europe and in the United States. Technology policy labs in particular aim to advance technology policies through research, education and thought leadership, thereby restoring confidence in the design and decision-making mechanisms needed to make such policies successful. Some current examples are:

- The Tech Policy Lab at the University of Washington focuses on Artificial Intelligence and influences both state and federal legislation.

- The Digital Technologies Policy Laboratory at University College London (UCL), whose current projects address the Internet of Things and online privacy.

- The EU Policy Lab, of the European Commission, which experiments with the design of services in priority thematic areas for the EU - such as shared economy, blockchain technologies or health.

Open Data Policy Labs

Within the technology policy labs it is also common to find some specialised in more specific subjects, as is the case of the Open Data Policy Labs. The aim here is to support decision makers in their work to accelerate the responsible re-use and exchange of data for the benefit of society and the equitable dissemination of social and economic opportunities associated with such data.

A clear example is the Open Data Policy Lab, recently launched by Microsoft and the GovLab to help government agencies at all levels identify best practices to improve the availability, reuse and usefulness of the data they manage - from developing effective legislative models to addressing the challenge of identifying and publishing high-value datasets needed to help address critical societal challenges.

Its work is to facilitate collaboration between governments, the private sector and society to address a number of obstacles that currently stand in the way of accessing data responsibly - including the absence of an enabling governance model, lack of internal capacity, or limited access to external knowledge and resources. To this end, the Open Data Policy Lab focuses on four main activities:

- Analysis: through research to identify best practices in the field of open data and inform about the development of data initiatives that contribute to economic and social development.

- Guidance: by developing methodologies, guidelines, toolkits and other materials to facilitate more effective data sharing and promote evidence-based decision making when addressing public policy issues.

- Community networks: building a community of data managers and decision makers in the public and private sectors to share knowledge, conduct collaborative work and stimulate data exchange.

- Action: Identifying key societal challenges that can benefit from open data and implementing proof-of-concept initiatives that demonstrate how to harness the power of open data to solve those challenges.

In short, public policy laboratories are promising tools that can definitively contribute to taking the step towards the expected third wave in the movement of open data, since they have all the elements necessary to confront and provide solutions in an agile manner to the limitations in current data governance models through openness that is respectful of data, based on public interests and built on collaborative action.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultan, World Wide Web Foundation.

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

Young people have consolidated in recent years as the most connected demographic group in the world and are now also the most relevant actors in the new digital economy. One in three internet users across the planet is a child. Furthermore, this trend has been accelerating even more in the current context of health emergencies, in which young people have exponentially increased the time they spend online while being much more active and sharing much more information on social networks. A clear example of the consequences of this incremental use is the need of online teaching, where new challenges are posed in terms of student privacy, while we already know of some initial cases related to problems in the management of fairly worrying data.

On the other hand, young people are more concerned about their privacy than we might initially think. However, they recognise that they have many problems in understanding how and for what purpose the various online services and tools collect and reuse their personal information.

For all these reasons, although in general legislation related to online privacy is still developing throughout the world, there are already several governments that now recognise that children - and minors in general - require special treatment with regard to the privacy of their data as a particularly vulnerable group in the digital context.

Therefore, minors already have a degree of special protection in some of the legislative frameworks of reference in terms of privacy at a global level, as the European (GDPR) or US (COPPA) regulations. For example, both set limits on the general age of legal consent for the processing of personal data (16 years in the GDPR and 13 years in COPPA), as well as providing additional protection measures such as requiring parental consent, limiting the scope of use of such data or using simpler language in the information provided about privacy.

However, the degree of protection we offer children and young people in the online world is not yet comparable to the protection they have in the offline world, and we must therefore continue to make progress in creating safe online spaces that have strong privacy measures and specific features so that minors can feel safe and be truly protected - in addition to continuing to educate both young people and their guardians in good practice in terms of managing personal data.

The Responsible Management of Children's Data (RD4C) initiative, promoted by UNICEF and The GovLab, was born with this objective in mind. The aim of this initiative is to raise awareness of the need to pay special attention to data activities involving children, helping us to better understand the potential risks and improve practices around data collection and analysis in order to mitigate them. To this end, they propose a number of principles that we should follow in the handling of such data:

- Participatory processes: Involving and informing people and groups affected by the use of data for and about children

- Responsibility and accountability: Establishing institutional processes, roles and responsibilities for data processing.

- People-centred: Prioritising the needs and expectations of children and young people, their guardians and their social circles.

- Damage prevention: Assessing potential risks in advance during the stages of the data lifecycle, including collection, storage, preparation, sharing, analysis and use.

- Proportional: Adjusting the extent of data collection and the length of data retention to the purpose initially intended.

- Protection of children's rights: Recognizing the different rights and requirements needed to help children develop to their full potential.

- Purpose-driven: specifying what the data is needed for and how its use can potentially benefit children's lives.

Some governments have also begun to go a step further and favour a higher degree of protection for minors by developing their own guidelines aimed at improving the design of online services. A good example is the code of conduct developed by the UK which - similarly to the R4DC - also calls for the best interests of children themselves, but also introduces a number of service design patterns that include recommendations such as the inclusion of parental controls, limitations on the collection of personal data or restrictions on the use of misleading design patterns that encourage data sharing. Another good example is the technical note published by the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD) for the protection of children on the Internet, which provides detailed recommendations to facilitate parental control in access to online services and applications.

At datos.gob.es, we also want to contribute to the responsible use of data affecting young people, and we also believe in participatory processes. That is why we have included data security and/or privacy issues in the field of education as one of the challenges to be resolved in the next Aporta Challenge. We hope that you will be encouraged to participate and send us all your ideas in this and other areas related to digital education before 18 November.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultan, World Wide Web Foundation.

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.