The Manifesto for a public data space has recently been published. The document raises the need to reinforce the importance of data in the current digital transformation process in this area. The document has been drawn up within the State Technical Committee of the Electronic Judicial Administration and was subsequently ratified by the competent Public Administrations in matters of Justice, i.e. the General State Administration through the Ministry of Justice and the Autonomous Communities that have assumed competence in this field, as well as the General Council of the Judiciary and the General State Prosecutor's Office.

Specifically, as is expressly recognised, it is "an instrument that seeks to improve the efficiency of Justice through data processing and to design public policies in the field of Justice, based on the consideration of data as a public good, in such a way as to guarantee both its production and its free access".

What are the main objectives to be achieved?

The document is part of a wider initiative called Data-driven Justice which, within the broader framework of the transformation of the public service of Justice, is conceived as a priority project for the Administration of Justice. Its main purpose is the creation of a secure, interoperable and reuse-oriented public data space. Specifically, it aims to:

- Promote a data-driven management model underpinning the transformation of Justice.

- Given that data must be considered a public good, it is considered a priority to guarantee free access to them.

- To promote a secure, interoperable and reuse-oriented public data space, which implies the need to address technical, organisational and, ultimately, legal challenges and problems. To this end, a governance model is proposed based on the configuration of access to data as a right, the promotion of interoperability, as well as, among other principles, the promotion of data literacy and the rejection of practices that prevent the re-use of data or, where appropriate, imply the recognition of exclusive rights.

- Ensure innovation in the field of Justice with a solution-oriented approach to concrete problems, in particular to promote cohesion and equality.

Difficulties and challenges from an open data and re-use perspective

This is undoubtedly a suggestive approach which, nevertheless, faces important challenges that go beyond the mere approval of formal documents and the promotion of legislative reforms.

Firstly, it is necessary to start from the existence of a plurality of subjects involved. To this end, the existence of a dual perspective in the public management of the judicial sphere must be emphasised. On the one hand, the Ministry of Justice or, as the case may be, the Autonomous Communities with transferred powers are the administrations that provide the material and personal resources to support management and, therefore, are responsible for exercising the powers relating to access and re-use of the information linked to their own sphere of competence. On the other hand, the Constitution reserves the exercise of the judicial function exclusively to judges and courts, which implies a significant role in the processing and management of documents. In this respect, the legislation grants an important role to the General Council of the Judiciary as regards access to and re-use of judicial decisions. Undoubtedly, the fact that the judicial governing body has ratified the Manifesto represents an important commitment beyond the legal regulation.

Secondly, although there has been significant progress since the approval in 2011 of a legislative framework aimed at promoting the digitisation of Justice, nevertheless, the daily reality of courts and tribunals often demonstrates the continued importance of paper-based management. Furthermore, major interoperability problems sometimes persist and, ultimately, the interconnection of the different technological tools and information systems is not always guaranteed in practice.

In order to address these challenges, two major initiatives have been promoted in recent months. On the one hand, the reform intended to be carried out by the Draft Act on Procedural Efficiency Measures in the Public Justice Service shows, in short, that the modernisation of the judiciary is still a pending objective. However, it should be borne in mind that this is not simply a purely technological challenge, but also requires important reforms in the organisational structure, document management and, in short, the culture that pervades a highly formalised area of the public sector. A major effort is therefore needed to manage the change that the Manifesto aims to promote.

With regard to open data and the re-use of public sector information, it is necessary to distinguish between purely administrative management, where the competence corresponds to the public administrations, as mentioned above, and judicial decisions, the latter being in the hands of the General Council of the Judiciary. In this respect, the important effort made by the judges' governing body to facilitate access to statistical information must be acknowledged. However, access to judicial decisions for re-use has significant restrictions which should be reconsidered in the light of European regulation. Even taking into account the progress made at the time with the implementation of the service of access to judicial decisions available through the CENDOJ, it is true that this is a model with significant limitations that may hinder the promotion of advanced digital services based on the use of data.

Even though the last attempt to regulate the singularities of the re-use of judicial information by the General Council of the Judiciary ended up being annulled by the Supreme Court, the aforementioned Draft Act contemplates a relevant measure in this respect. Specifically, within the framework of the electronic archiving of documents and files, it entrusts the General Council of the Judiciary with the regulation of "the re-use of judgments and other judicial decisions by digital means of reference or forwarding of information, whether or not for commercial purposes, by natural or legal persons to facilitate access to them by third parties".

More recently, at the end of July, the Council of Ministers approved a second legislative initiative that is already being processed in the Spanish Parliament and which incorporates some measures specifically dedicated to the promotion of digital efficiency. Specifically, in relation to the electronic judicial file, the reform aims to go beyond the document-based management model and proposes a paradigm shift based on the establishment of the general principle of a data-based justice system that, among other possibilities, facilitates "automated, proactive and assisted actions". With regard to open data and the reuse of information, the draft legislation includes a specific title that provides for the publication of open data on the Justice Administration Portal according to interoperability criteria and, whenever possible, in formats that allow automatic processing.

In short, data-driven management in the judicial sphere and, in particular, access to judicial information for reuse purposes requires a process of in-depth reflection in which not only the competent public bodies and legal publishers offering access to jurisprudence but, with a broader scope, the various legal professions and society in general can participate. Beyond the promotion of suggestive initiatives such as the Forum on the Digital Transformation of Justice, the first edition of which took place a few months ago, and the timely organisation of academic events where this debate can take place, such as the one held last October, ultimately we must start from an elementary principle: the need to promote a management model based on the opening up of information by default and by design. Only on this premise can the effective re-use of information in the public service of Justice be promoted definitively and with the appropriate legal guarantees.

Therefore, in view of the important legal reforms that are being processed, the time seems to have come to make a definitive commitment to the value of data in the judicial sphere under the protection of the objectives that the aforementioned Manifesto intends to address.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec).

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

Digital transformation affects all sectors, from agriculture to tourism and education. Among its objectives is the optimization of processes, the improvement of the customer experience and even the promotion of new business models.

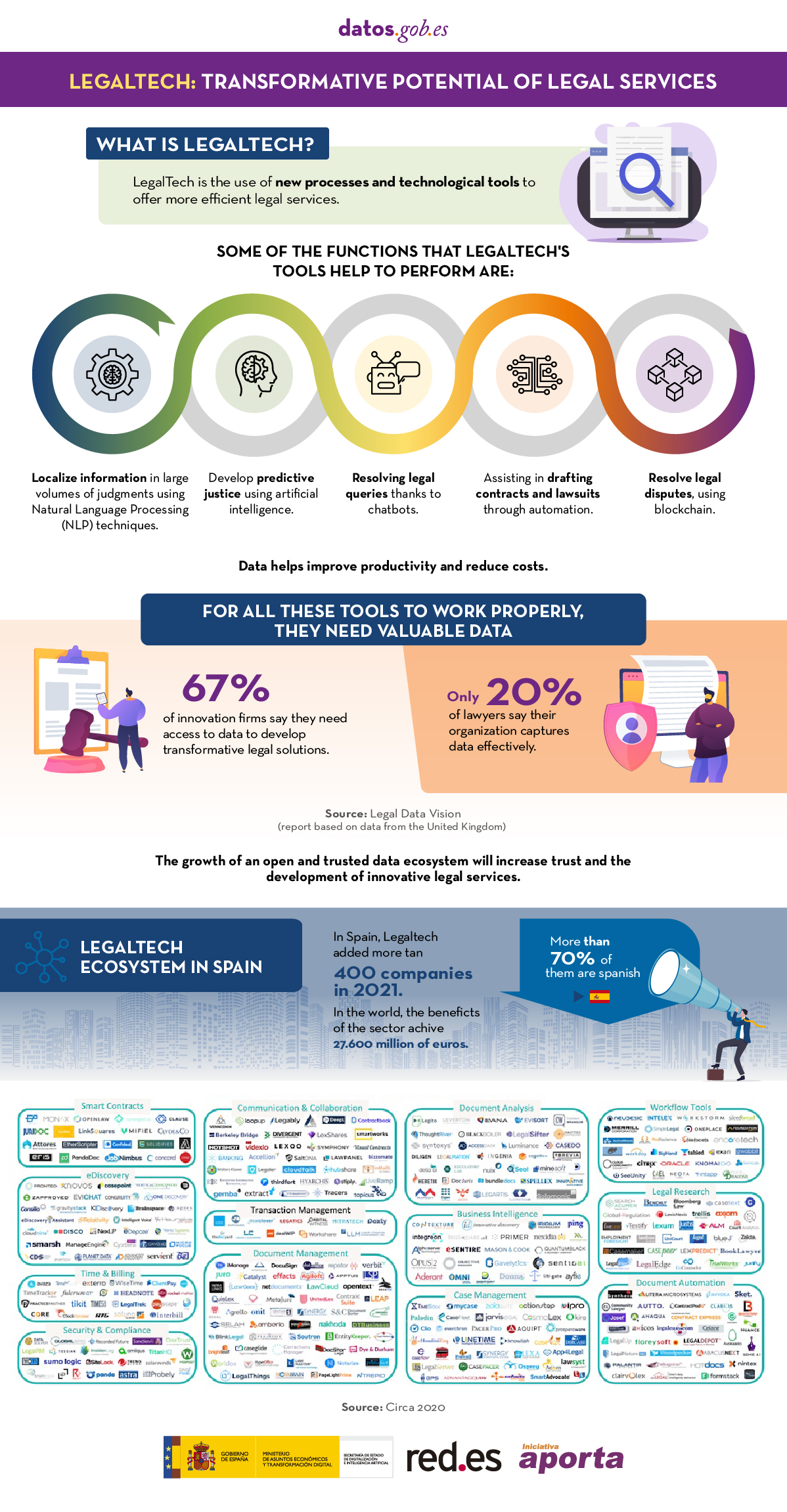

The legal sector is no exception, which is why in recent years we have seen a boom in solutions and tools aimed at helping lawyers to perform their work more efficiently. This is what is known as LegalTech.

What is LegalTech?

The LegalTech concept refers to the use of new technological processes and tools to offer more efficient legal services. It is therefore an extensive concept, applying both to tools that facilitate the execution of tasks (e.g. financial management) and to services that take advantage of disruptive technologies such as artificial intelligence or blockchain.

The term LawTech is sometimes used as a synonym for LegalTech. Although some legal scholars say that they are distinct terms and should not be confused, there is no consensus and in some places, such as the UK, LawTech is widely used as a substitute for LegalTech.

Examples of LegalTech or LawTech tools

Through the application of different technologies, these tools can perform different functions, such as:

- Locating information in large volumes of judgments. There are tools capable of extracting the content of court rulings, using Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. The aim of these tools is to facilitate the filtering and location of information of interest, as well as to make it available to the user in a visual way. This helps lawyers to carry out a better investigation and, consequently, to reduce the preparation time of cases and to define more solid procedural strategies. An example of a tool in this area is Ross Intelligence.

- Perform predictive analytics. In the market we also find tools aimed at analyzing sentences and making predictions that anticipate the behaviors and outcomes of, using artificial intelligence. These tools try to answer questions such as how long a judicial process will take, what is the most probable sentence or if there is a possibility of appeal. Tools of this type are LexMachina, Blue J, IBM's Watson or Jurimetria.

- Solving legal queries. Using AI-based conversational assistants (chatbots), answers can be given to various questions, such as how to overcome parking fines, how to appeal bank fees or how to file a complaint. These types of tools free lawyers from simple tasks, allowing them to devote their time to more valuable activities. An example of legal chatbots is DoNotPay.

- Assist in drafting contracts and lawsuits. LegalTech tools can also help automate and simplify certain tasks, generating time and cost savings. This is the case of Contract Express, which automates the drafting of standard legal documents.

- Resolving legal disputes. There are some disputes that can be resolved simply using open source technology tools such as Kleros, an online dispute resolution protocol o. Kleros uses blockchain to resolve disputes as fairly as possible.

The role of open data in Legal Tech

For all these tools to work properly, optimizing the work of jurists, it is necessary to have valuable data. In this sense, open data is a great opportunity.

According to the Legal Data Vision initiative, which uses UK data and was launched in March 2022, by LawtechUK and the Open Data Institute 67% of innovation companies claim to need access to data to develop transformative legal solutions and only 20% of lawyers claim that their organization captures data effectively. This initiative aims to promote responsible access to and use of legal data to drive innovation in the industry and deliver results that benefit society.

According to Gartner, legal areas are set to increase spending on technology solutions by 200% by 2025. In countries such as France, a large number of start-ups focused on this area are already emerging, many of which reuse open data. In Spain we are also experiencing an expansion of the sector, which will enable improvements to be implemented in the processes and services of legal companies. In 2021 there were more than 400 companies operating in this field and, globally, according to figures from Stadista, the sector generated more than €27 billion.

However, for this field to make further progress, it is necessary to promote access to judgments in machine-readable formats that allow mass processing.

In short, this is a booming market, thanks to the emergence of disruptive technologies. Legal firms need access to up-to-date, quality information that will enable them to perform their work more efficiently. One of the methods to achieve this is to take advantage of the potential of open data.

(Click here to access the accessible version)

Content prepared by the datos.gob.es team.

Why a Royal Decree-Law?

In the plenary session of the Congress of Deputies held on December 2, 2021, Royal Decree-Law 24/2021, of November 2, on the transposition of several European Union directives, including Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of June 20, 2019, on open data and the reuse of public sector information, was validated. With this new regulation, the provisions of Law 37/2007, of November 16, on the reuse of public sector information have been modified.

What are the main novelties of this regulation?

The content of the new legal regulation is substantially focused on the incorporation of the provisions of the 2019 Directive to the text of the Spanish Law of 2017, although it is necessary to take into account that those precepts that could be directly applied were already in force since the end of the deadline for its transposition in July 2021. However, apart from updating some already outdated legal references -specifically on personal data protection, public sector legal regime and administrative procedure-, on the occasion of the transposition, some relevant novelties have been added that go beyond the mere adaptation of the European regulation. Thus:

- From the point of view of its subjective scope, the legislation will be applicable to all entities to which, according to the terms provided in their regulatory regulations, the regulations governing the common administrative procedure are applicable. This would be the case, for example, of private law entities linked to or dependent on Public Administrations when they exercise administrative powers.

- The reuse of documents to which access is excluded or limited for reasons of protection of sensitive information on critical infrastructures is expressly excluded from the legal regulation.

- As regards high-value data, alongside those established by the European Commission (i.e. geospatial, Earth observation and environment, meteorology, statistics, companies, as well as mobility), additional datasets may also be specified by the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation, specifically through the selection and updating carried out by the Data Office Division with the collaboration of the stakeholders, both public and private. In this regard it is important to recall that, as a general rule, these data will be freely available, machine-readable, provided through APIs and, where appropriate, provided in the form of bulk download.

- When making high-value data available free of charge could have a substantial impact on the budget of bodies and entities governed by public law that must obtain income to finance their public service activity, the Public Administration to which they are linked, or on which they depend, will be competent to exempt them from this obligation. Consequently, such bodies and entities would not be able to take this decision on their own.

- The scope of the reusable public information catalog is projected -at least potentially- beyond the scope of the General State Administration and its public bodies, so that other entities that decide to create their own catalogs that are interoperable with the national one are required to do so. This is an instrument whose practical relevance is reinforced by the fact that, through it, information will be provided on the rights legally provided for reuse, help systems will be offered and datasets will be made available in accessible, easy to locate and reusable formats.

- En cuanto al sometimiento a las normas legales sobre procedimiento de tramitación de solicitudes de reutilización, las sociedades mercantiles, centros de enseñanza, organismos de investigación o entidades que realicen actividades de investigación quedarán exentos.

- Regarding the submission to the legal rules on the procedure for processing requests for reuse, corporations, educational institutions, research organizations or entities that carry out research activities will be exempted.

- From the organizational point of view, each entity is required to designate a unit responsible for ensuring the availability of its information. Among the functions that will correspond to these units are those related to the coordination of reuse activities with existing policies on publications, administrative information and electronic administration; providing information on which bodies are competent in each area; promoting the updating and making information available in appropriate formats; as well as promoting awareness and training activities.

In any case, in the aforementioned parliamentary session, it was unanimously decided to proceed with the processing of the initiative as a bill through the urgency procedure, one of the possibilities provided for in Article 86 of the Constitution when it comes to validating decree-laws. Consequently, a legislative initiative will have to be processed following the regulatory channels established for this type of cases, which will allow the various parliamentary groups to propose amendments that, if approved, would be incorporated into the final text of the legislation on the reuse of public sector information and open data.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec).

The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

Just a few days ago has been officially presented the Digital Charter of Rights. It is an initiative that has had a wide representation of civil society since, on the one hand, a wide and diverse work team has been in charge of its drafting and, on the other, during the procedure of its preparation a public participation procedure so that the appropriate proposals and observations could be made from civil society.

What is the value of the charter?

In recent years, important advances have been made in Spain in regulating the use of technology in various fields. This has happened, for example, with the use of electronic means by Public Administrations, the protection of personal data, electronic trust services, the digital transformation of the financial sector or, without being exhaustive, the conditions for remote work. Numerous regulatory initiatives have also been promoted by the European Union in which the use of data plays a very relevant role. Among them are theDirective (EU) 2019/770 of the European Parliament and of the Council, of May 20, 2019, relating to certain aspects of the contracts for the supply of digital content and services, and the Directive 1024/2019, on open data and reuse of public sector information. Even, in the immediate future, the approval of two European regulations on data governance and Artificial intelligence, projects directly related to EU Digital Strategy which is promoted by the European Commission.

Given this panorama of intense normative production, it could be considered to what extent a new initiative such as the one represented by this Charter. In the first place, it must be emphasized that, unlike those previously mentioned, the Charter is not a legal norm in the strict sense, that is, it does not add new obligations and, therefore, its provisions lack normative value. In fact, as expressly stated in it, its objective is not "to discover digital rights by pretending that they are something different from the fundamental rights already recognized or that new technologies and the digital ecosystem are erected by definition as a source of new rights" but, rather, "outline the most relevant in the environment and digital spaces or describe the instrumental or auxiliary rights of the former."

Beyond the non-existent legal scope of its content, the Charter aims to highlight the impact and consequences that digital scenarios pose for the effectiveness of rights and freedoms, thus suggesting some guidelines in the face of the new challenges that said technological context poses for the interpretation and application of rights today, but also in their more immediate future evolution, which can already be predicted. Taking into account these claims, the call for regulatory compliance from the design in digital environments acquires singular relevance (section I.4),

What is the prominence that the Charter has given to data?

With regard to the digital rights of citizens in their relations with Public Administrations, in Section 3 (Rights of participation and conformation of the public space) some provisions have been established where the protagonism of the data is unquestionable (Section XVIII) :

- Thus, it is established that the principle of transparency and reuse of public sector data will guide the actions of the digital Administration, although its scope is conditioned by what the applicable regulations establish. In any case, this principle is reinforced with the promotion of publicity and accountability. Likewise, the portability of the data and the interoperability of the formats, systems and applications will be ensured, in the terms provided by the current legal system. Specifically (Section 5, Section XXI), the use for the common good of personal and non-personal data, whether they come from the public or private sector, is recognized, including among the purposes the archive in the public interest, research, statistics , as well as innovation and development. In this sense,

- The importance of transparency about the use of artificial intelligence instruments is also emphasized, in particular, about the data used, its margin of error, its scope of application and its decision-making or non-decision-making nature. Beyond its incidence in the public sector, non-discrimination regarding the use of data is generally prohibited (Section 5, Section XXV), and adequate conditions of transparency, auditability, explicability, traceability, supervision must be established. human rights and governance.

- Likewise, the need to carry out an impact assessment on digital rights is established when designing algorithms in the case of automated or semi-automated decision-making. It therefore seems inexcusable that such an evaluation pays special attention to the biases that may occur with regard to the data used and the treatment that may be carried out in the decision-making process. Impact assessment from the perspective of ethical principles and rights related to artificial intelligence is also specifically contemplated for the workplace (Section 4, Section XIX), with special attention to eventual discrimination and conciliation rights.

- Singular importance is given to the need for the Administrations to offer an understandable motivation in natural language for the decisions they adopt using digital means, having to justify especially what criteria for applying the standards have been used and, therefore, the data that have been used. been able to handle to that effect.

- With regard specifically to the health system (Section 5, Section XXIII), on the one hand, it is required to ensure interoperability, access and portability of patient information and, in relation to technological devices developed for therapeutic purposes or care, an attempt is made to prevent its free use from being conditioned on the transfer of the patient's personal data.

Thus, although the Charter of Digital Rights does not incorporate legal obligations by itself, it nevertheless offers interpretive criteria that may be relevant in the process of interpretation and application of the current legislative framework, as well as serve as guidance when promoting future regulatory projects.

On the other hand, even when it does not establish legally enforceable rights, its content establishes relevant measures aimed at the public powers, in particular with regard to the General State Administration and the entities of the state public sector since, ultimately, It is an initiative promoted and formally assumed by the state government.

In short, their forecasts are of particular importance with regard to open data and the reuse of public sector information given that in the coming months important regulations will have to be approved both at the state and European level, so that the content of the Charter can acquire a singular role in the development and application of these norms.

Content written by Julián Valero, professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec).

The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

In the more traditional conception of the right of access and transparency of public sector entities, obtaining information requires, in advance, the processing of an administrative procedure that ends with the corresponding resolution by which the requested information is granted or denied. However, in the model based on open data, a substantial change occurs: on the one hand, the request and corresponding resolution are only considered as a residual measure; and, on the other hand, access to the data will take place without the need for a formalised administrative act.

In this regard, Law 37/2007 contemplates both possibilities, expressly enabling public administrations and bodies to provide standard licenses in digital format that can be processed automatically. It also states a preference for those types of licenses that establish the minimum restrictions and establishes the minimum content that must be incorporated:

- information concerning the specific purpose for which the re-use is granted

- if reuse for commercial purposes is allowed

- the duration of the license

- the obligations of each party, as well as the responsibilities for use

- the free nature of the re-use or, where appropriate, the applicable fee

In the case of the General State Administration, the general rule is the availability of the data without any specific conditions, simply by complying with a series of general requirements:

- citing the source of the data

- indicate the date of the last update, where appropriate, via metadata

- not to distort the meaning of the information

- keep the metadata on the applicable conditions for reuse

Consequently, except in the exceptional cases in which it is necessary to make a request or there is a specific regime with certain additional requirements, the general conditions of re-use for the state public sector area will be applicable to those who intend to re-use data provided by entities in this area, including processing such as copying, dissemination, modification, adaptation, extraction, reordering and combination of information.

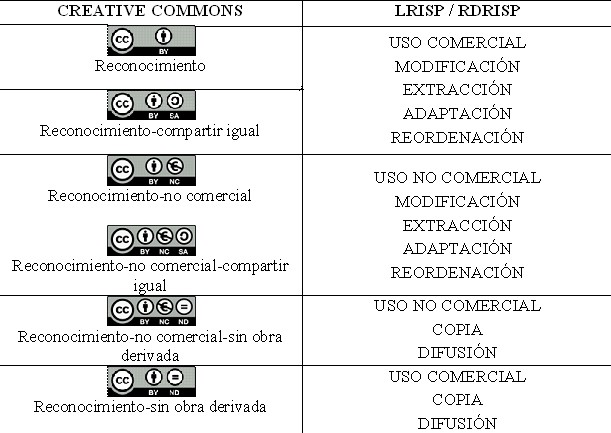

Despite the advantages of using licenses, there is no tradition in the Spanish public sector of standardizing the conditions for reusing information through this instrument. Rather, it is a figure typical of the Anglo-Saxon legal context which, through European Union law, has been incorporated into the regulation on the re-use of public sector information and open data. However, licences can be a very useful tool in facilitating the integration of data from different sources. Indeed, on the one hand, they allow to promote interoperability in legal terms, since they simplify the analysis and comparison from the perspective of the conditions to which the re-using agents are submitted. On the other hand, they make the automated processing of the conditions in which reuse can take place more dynamic and without greater formalities. Therefore, reducing the need to carry out manual checks on the viability of the use of the data in each specific case according to what each entity has established according to its own criteria.

The preferential option of setting general conditions for reuse means that, except in the publishing field and in particular for journals, the use of licences by the public sector is not very widespread in Spain; perhaps because it is a legal figure that is alien to our cultural tradition based on formal institutions such as the act and the administrative procedure. That is, on the unilateral decision of the Administration that must take into account the circumstances of the specific case. In fact, the term license is normally used to refer to an administrative act by which a private activity is permitted or, in the case of public goods, its use under certain conditions.

Given the low level of implementation of licences in Spain in the field of re-use of public sector information - except for some regional and municipal initiatives - it could be asked to what extent the aforementioned general conditions are compatible with the most widespread licences, so that this analysis serves as a reference when assessing their approximate equivalence. The case of the Creative Commons licences is of particular interest, as these are the licences adopted by the European Commission following the comparative study carried out previously.

By way of example, the conditions established at the state level -given their greater projection- could be compared with the aforementioned licenses which, moreover, from version 4.0 onwards include not only content but also data. In this regard, as shown graphically in the table below, the possibilities granted by the Creative Commons licenses - summarized in the left column - must be contrasted with the conditions set by law - briefly explained in the right column - both in the articles of Law 37/2007 (LRISP) and in Royal Decree 1495/2011 (RDRISP):

Source: Clabo, N.; Ramos-Vielba, I. (2015). Reuse of open data in the public administration in Spain and use of model licenses. Revista Española de Documentación Científica, 38 (3): e097, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/redc.2015.3.1206

Therefore, even if the conditions established by the Spanish legislation for the re-use of public sector information have a wider scope in terms of content, it has been considered that there is a substantial equivalence between those conditions and the ones contemplated by these licenses, in particular version CC BY 4.0. In any case, the complete wizard of the European Data Portal is a very useful tool when it comes to making an exhaustive comparison of the conditions for reusing public sector information in Spain with each of the specific types of license that exist beyond the aforementioned.

In spite of the doubts raised by some of its provisions in this area, in view of the forthcoming transposition of Directive 2019/1024 and its clear commitment to the use of licences, it seems that the time has come to open up the legal debate in Spain once and for all on its use in the field of re-use of public sector information and open data.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec).

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

María Jesús González-Espejo is, with Laura Fauqueur, co-founder of the Institute of Legal Innovation (Instituto de Innovación Legal), a company specialized in supporting professionals, law firms and organizations in innovation and digital transformation projects. For this, they are based on 4 pillars: consulting, training, events and information.

Datos.gob.es has spoken with her to tell us the role of open data to get a more transparent judicial system.

What is the impact of data and new technologies in the legal sector? Why is it important to transform this sector?

Technology and data can and will transform the sector in many ways. On the one hand, technology and data impact on the legal framework. In effect, new technologies are demanding new regulations and also generating new business sources for lawyers who specialize and are able to advise on these topics.

On the other hand, technology allows jurists to better manage their work and their organizations. And nowadays, although later than other sectors, jurists know that they can be much more efficient if they use technology for certain tasks, especially those where data and its management are relevant: issues management; Customer Management; People Management; knowledge management; financial management and legal prediction. The impact of these technologies on legal professionals and their organizations is enormous.

Finally, there are legal services that can be offered through technology, improving its provision. For example, chatbots allow providing advice in a more efficient manner, and contract automation tools allow generate contract easily and without the need for professional support. These types of technologies will clearly impact the employment market.

The Institute of Legal Innovation seeks to help in the digital transformation of the sector through different projects. What is the role of open data in this transformation process?

I believe that the Institute of Legal Innovation has been one of the first private operators that has claimed the need for more open data. In the legal sector there is a series of data that are key to the development of more and better Legal Tech: judgments, resolutions and other information that result from legal procedures and that must be public. Many of the agencies that keep this information (CGPJ, CENDOJ, Registrars, Notaries, Ministry of Justice, Bar Associations, etc.) provide us with great reports and statistics, but not the data. In our opinion, that is the next step that must be taken to produce the real "Legal Tech Revolution", as I claimed during my speech in the Senate.

What is Legal Design Thinking? What advantages can it bring?

Legal Design Thinking is a methodology, based on Design Thinking. The origin of Design Thinking is located in the 50s in Stanford University in the US, but it is really in the 90s, hand in hand with David Kelley, when Design Thinking begins to be conceived as we know it today. In the 90s, also professors of this university began to investigate the applications of this methodology to the legal field. Parallel to this North American school, in Helsinki, several researchers of different specializations (legal, design, etc.) develop projects focused on the so-called Visual Design Thinking and its application to the legal sector.

This methodology helps to solve legal problems, understanding as such, those that refer to the functioning of the legal system or legal service providers, Legal Design Thinking (LDC). The word "problem" must be understood not in the traditional sense, as something negative, but in a broader one, as a challenge or situation that can be improved through creativity. This activity is the core idea on which Design Thinking is articulated. The other main point of the Design Thinking discipline is the client, the user, the recipient of the service, the contract, the rule, the sentence. In summary, Legal Design Thinking is a discipline that fits into the heuristic and whose main objective is the search for solutions to problems through creativity, always putting people at the center of the activity.

This discipline is very useful for many of the needs that law firms and other organizations in the legal sector have nowadays, such as the revision of their business models; the identification and development of new products or services; the understanding of customer journey to better meet customer needs or the operation of equipment.

One of the challenges to address the digital transformation of the legal sector is the lack of personnel with technological skills and knowledge, something that also happens in other sectors. What are the necessary capabilities and how can they be acquired?

Acquiring technological knowledge is not easy, but it is possible. There are already some complete works that analyse the Legal Tech in depth. In addition, there are numerous conferences, congresses, etc. where you can learn about the subject.

However, it is more complex to acquire the necessary skills such as project management; leadership; change management; time management; etc. The reasons are that, on the one hand, our sector has its own idiosyncrasy and requires customized training; but at the same time jurists are usually short on time and, consequently, many courses do not achieve sufficient capacity. So it is not always easy to find suitable training offer.

You also organize hackathons, such as #HackTheJustice (2017) and JustiApps (2014). Among other issues, the aim is to develop applications that help improve the efficiency and transparency of the sector. How has the reception of these events been? What are the challenges to access and reuse legal public data?

The reception of these events has been very good. In fact, they have received support from many relevant institutions such as the Ministry of Justice, the General Council of Notaries and companies such as Amazon, Banco Santander, Ilunión, Everis, Thomson Reuters, WKE, etc. In both editions we counted on a sufficient number of participants who also had very different profiles: lawyers, judges, students, etc. For all of them, working for a weekend with designers and developers of apps has been a unique experience that has changed their lives. Several of our participants have decided to turn, in part, their professional lives around after participating in our hackathons.

When we organize the first hackathon, we realized that there were almost no legal datasets and we made a round of calls to try to get them. The answers were not very positive. Since our first hackathon, there have not been major changes. So there is still room for work to continue asking the institutions to open the data they own.

What measures do you consider necessary to encourage the opening and reuse of legal open data?

The most important measure seems simple at first sight: all administrations that are responsible for data susceptible to becoming datasets should open them. Beginning with the Ministry of Justice and continuing through the CENDOJ or Registrars. All datasets should be inventoried, so that whoever wants to locate them does not have to spend days on their location.

To encourage reuse, perhaps a Legal Datathon could be organized once a year. Of course, hackathons and such activities also help and it would be great if some public institution wanted to organize them. In addition, the creation of Legal Tech incubators in professional colleges would support entrepreneurs who reuse this data. Finally, training in data, big data, transparency, etc. to law students and even professionals is perhaps the most necessary and practical measure that could be implemented.

The Legal Innovation Institute is also an incubator of Legal Tech projects. Based on your experience, how is the situation in Spain regarding innovation in the legal sector? Could you tell us about some of the projects you have in hand?

The situation is better in some aspects and worse in others. Spain has a clear advantage: the potential of the Spanish-speaking market. And several disadvantages: lack of enterprising spirit in technology among jurists; lack of institutional support; lack of training in the necessary skills and knowledge; etc. However, I am optimistic and I think that, in Spain,we are becoming aware that we are facing a sector with great potential. In the coming years, I think that we can become the cradle of many Legal Tech that will transform professionals, legal organizations and how many legal services are provided today.

One of the most relevant projects that we have in hand is the launch of the first Legal Tech comparator. It will be a very useful tool for any firm or professional who wants to know what technology is available in the market.