Open health data is one of the most valuable assets of our society. Well managed and shared responsibly, they can save lives, drive medical discoveries, or even optimize hospital resources. However, for decades, this data has remained fragmented in institutional silos, with incompatible formats and technical and legal barriers that made it difficult to reuse. Now, the European Union is radically changing the landscape with an ambitious strategy that combines two complementary approaches:

- Facilitate open access to statistics and non-sensitive aggregated data.

- Create secure infrastructures to share personal health data under strict privacy guarantees.

In Spain, this transformation is already underway through the National Health Data Space or research groups that are at the forefront of the innovative use of health data. Initiatives such as IMPACT-Data, which integrates medical data to drive precision medicine, demonstrate the potential of working with health data in a structured and secure way. And to make it easier for all this data to be easy to find and reuse, standards such as HealthDCAT-AP are implemented.

All this is perfectly aligned with the European strategy of the European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS), officially published in March 2025, which is also integrated with the Open Data Directive (ODD), in force since 2019. Although the two regulatory frameworks have different scopes, their interaction offers extraordinary opportunities for innovation, research and the improvement of healthcare across Europe.

A recent report prepared by Capgemini Invent for data.europa.eu analyzes these synergies. In this post, we explore the main conclusions of this work and reflect on its relevance for the Spanish open data ecosystem.

-

Two complementary frameworks for a common goal

On the one hand, the European Health Data Space focuses specifically on health data and pursues three fundamental objectives:

- Facilitate international access to health data for patient care (primary use).

- Promote the reuse of this data for research, public policy, and innovation (secondary use).

- Technically standardize electronic health record (EHR) systems to improve cross-border interoperability.

For its part, the Open Data Directive has a broader scope: it encourages the public sector to make government data available to any user for free reuse. This includes High-Value Datasets that must be published for free, in machine-readable formats, and via APIs in six categories that did not originally include "health." However, in the proposal to expand the new categories published by the EU, the health category does appear.

The complementarity between the two regulatory frameworks is evident: while the ODD facilitates open access to aggregated and non-sensitive health statistics, the EHDS regulates controlled access to individual health data under strict conditions of security, consent and governance. Together, they form a tiered data sharing system that maximizes its social value without compromising privacy, in full compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Main benefits computer by user groups

The report looks at four main user groups and examines both the potential benefits and challenges they face in combining EHDS data with open data.

-

Patients: Informed Empowerment with Practical Barriers

European patients will gain faster and more secure access to their own electronic health records, especially in cross-border contexts thanks to infrastructures such as MyHealth@EU. This project is particularly useful for European citizens who are displaced in another European country. .

Another interesting project that informs the public is PatientsLikeMe, which brings together more than 850,000 patients with rare or chronic diseases in an online community that shares information of interest about treatments and other issues.

-

Potential health professionals subordinate to integration

On the other hand, healthcare professionals will be able to access clinical patient data earlier and more easily, even across borders, improving continuity of care and the quality of diagnosis and treatment.

The combination with open data could amplify these benefits if tools are developed that integrate both sources of information directly into electronic health record systems.

3. Policymakers: data for better decisions

Public officials are natural beneficiaries of the convergence between EHDS and open data. The possibility of combining detailed health data (upon request and authorisation through the Health Data Access Bodies that each Member State must establish) with open statistical and contextual information would allow for much more robust evidence-based policies to be developed.

The report mentions use cases such as combining health data with environmental information to assess health impacts. A real example is the French Green Data for Health project, which crosses open data on noise pollution with information on prescriptions for sleep medications from more than 10 million inhabitants, investigating correlations between environmental noise and sleep disorders.

4. Researchers and reusers: the main immediate beneficiaries

Researchers, academics and innovators are the group that will most directly benefit from the EHDS-ODD synergy as they have the skills and tools to locate, access, combine and analyse data from multiple sources. In addition, their work already routinely involves the integration of various data sets.

A recent study published in PLOS Digital Health on the case of Andalusia demonstrates how open data in health can democratize research in health AI and improve equity in treatment.

The development of EHDS is being supported by European programmes such as EU4Health, Horizon Europe and specific projects such as TEHDAS2, which help to define technical standards and pilot real applications.

-

Recommendations to maximize impact

The report concludes with four key recommendations that are particularly relevant to the Spanish open data ecosystem:

- Stimulate research at the EHDS-open data intersection through dedicated funding. It is essential to encourage researchers who combine these sources to translate their findings into practical applications: improved clinical protocols, decision tools, updated quality standards.

- Evaluate and facilitate direct use by professionals and patients. Promoting data literacy and developing intuitive applications integrated into existing systems (such as electronic health records) could change this.

- Strengthen governance through education and clear regulatory frameworks. As EHDS technical entities become operationalized, clear regulation defining common regulatory frameworks will be essential.

- Monitor, evaluate and adapt. The period 2025-2031 will see the gradual entry into force of the various EHDS requirements. Regular evaluations are recommended to assess how EHDS is actually being used, which combinations with open data are generating the most value, and what adjustments are needed.

Moreover, for all this to work, the report suggests that portals such as data.europa.eu (and by extension, datos.gob.es) should highlight practical examples that demonstrate how open data complements protected data from sectoral spaces, thus inspiring new applications.

Overall, the role of open data portals will be fundamental in this emerging ecosystem: not only as providers of quality datasets, but also as facilitators of knowledge, meeting spaces between communities and catalysts for innovation. The future of European healthcare is now being written, and open data plays a leading role in that story.

Do you know why it is so important to categorize datasets? Do you know the references that exist to do it according to the global, European and national standards? In this podcast we tell you the keys to categorizing datasets and guide you to do it in your organization.

- David Portolés, Project Manager of the Advisory Service

- Manuel Ángel Jáñez, Senior Data Expert

Listen to the full podcast (only available in Spanish)

Summary / Transcript of the interview

1. What do we mean when we talk about cataloguing data and why is it so important to do so?

David Portolés: When we talk about cataloguing data, what we want is to describe it in a structured way. In other words, we talk about metadata: information related to data. Why is it so important? Because thanks to this metadata, interoperability is achieved. This word may sound complicated, but it simply means that systems can communicate with each other autonomously.

Manuel Ángel Jañez: Exactly, as David says, categorizing is not just labeling. It is about providing data with properties that make it understandable, accessible and reusable. For that we need agreements or standards. If each producer defines their own rules, consumers will not be able to interpret them correctly, and value is lost. Categorizing is reaching consensus between the general and the specific, and this is not new: it is an evolution of library documentation, adapted to the digital environment.

2. So we understand that interoperability is speaking the same language to get the most out of it. What references are there at global, European and national level?

Manuel Ángel Jáñez: The way to describe data is in an open way, using standards or reference specifications, of frames.

-

Globally: DCAT (a W3C recommendation) allows you to model catalogs, datasets, distributions, services, etc. In essence, all the entities that are key and that are then reused in the rest of the profiles.

-

At the European level: DCAT-AP, the application profile in data portals in the European Union, particularly those corresponding to the public sector. This is essentially what is used for the Spanish profile, DCAT-AP-ES.

-

In Spain: DCAT-AP-ES, is the context in which more specific restrictions are incorporated at the Spanish level. It is a profile based on the 2013 Technical Standard for Interoperability (NTI). This profile adds new features, evolves the model to make it compatible with the European standard, adds features related to high-value sets (HVDs), and adapts the standard to the present of the data ecosystem.

David Portolés: With a good description, the reuser can search, retrieve and locate the datasets that are of interest to them and, on the other hand, discover other new datasets that they had not contemplated. The standards, the models, the shared vocabularies. The main difference between them is the degree of detail they apply. The key is to reach the compromise between being as general as possible so that they are not restrictive, but, on the other hand, it is necessary to be specific, it is necessary that they are also specific. Although we talk a lot about open data, these standards also apply to protected data that can be described. The universe of application of these standards is very broad.

3. Focusing on DCAT-AP-ES, what help or resources are there for a user to implement it?

David Portolés: DCAT-AP-ES is a set of rules and basic application models. Like any technical standard, it has an application guide and, in addition, there is an online implementation guide with examples, conventions, frequently asked questions and spaces for technical and informative discussion. This guide has a very clear purpose, the idea is to create a community around this technical standard, with the purpose of generating a knowledge base accessible to all, a transparent and open support channel for anyone who wants to participate.

Manuel Ángel Jañez: The available resources do not start from zero. Everything is aligned with European initiatives such as SEMIC, which promotes semantic interoperability in the EU. We want a living and dynamic tool that evolves with the needs, under a participatory approach, with good practices, debates, harmonisation of the profile, etc. In short, the aim is for the model to be useful, robust, easy to maintain over time and flexible enough so that anyone can participate in its improvement.

4. Is there any existing thematic implementation in DCAT-AP-ES?

Manuel Ángel Jáñez: Yes, important steps have been taken in that direction. For example, the model of high-value sets has already been included, key for data relevant to the economy or society, useful for AI, for example. DCAT-AP-ES is inspired by profiles such as DCAT-AP v2.1.1 (2022) that incorporates some semantic improvements, but there are still thematic implementations to be incorporated into DCAT-AP-ES, such as data series. The idea is that thematic extensions will enable modelling for specific datasets.

David Portolés: As Manu says, the idea is that he is a living model. Future possible extensions are:

- Geographical data: GeoDCAT-AP (European).

- Statistical data: StatDCAT-AP.

In addition, future directives on high-value data will have to be taken into account.

5. And what are the next objectives for the development of DCAT-AP-ES?

David Portolés: The main objective is to achieve full adoption by:

-

Vendors: To change the way they offer and disseminate their metadata relative to their datasets with this new paradigm

-

Reusers: that integrate the new profile in their developments, in their systems, and in all the integrations they have made so far, and that they can make much better derivative products.

Manuel Ángel Jáñez: Also to maintain coherence with international standards such as DCAT-AP. We want to continue to be committed to an agile, participatory technical governance model aligned with emerging technologies (such as protected data, sovereign data infrastructures and data spaces). In short: that DCAT-AP-ES is useful, flexible and future-prepared.

Interview clips

1. Why is it important to catalog data?

2. How can we describe data in open formats?

Collaborative culture and citizen open data projects are key to democratic access to information. This contributes to free knowledge that allows innovation to be promoted and citizens to be empowered.

In this new episode of the datos.gob.es podcast, we are joined by two professionals linked to citizen projects that have revolutionized the way we access, create and reuse knowledge. We welcome:

- Florencia Claes, professor and coordinator of Free Culture at the Rey Juan Carlos University, and former president of Wikimedia Spain.

- Miguel Sevilla-Callejo, researcher at the CSIC (Spanish National Research Council) and Vice-President of the OpenStreetMap Spain association.

Listen to the full podcast (only available in Spanish)

Summary / Transcript of the interview

1. How would you define free culture?

Florencia Claes: It is any cultural, scientific, intellectual expression, etc. that as authors we allow any other person to use, take advantage of, reuse, intervene in and relaunch into society, so that another person does the same with that material.

In free culture, licenses come into play, those permissions of use that tell us what we can do with those materials or with those expressions of free culture.

2. What role do collaborative projects have within free culture?

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: Having projects that are capable of bringing together these free culture initiatives is very important. Collaborative projects are horizontal initiatives in which anyone can contribute. A consensus is structured around them to make that project, that culture, grow.

3. You are both linked to collaborative projects such as Wikimedia and OpenStreetMap. How do these projects impact society?

Florencia Claes: Clearly the world would not be the same without Wikipedia. We cannot conceive of a world without Wikipedia, without free access to information. I think Wikipedia is associated with the society we are in today. It has built what we are today, also as a society. The fact that it is a collaborative, open, free space, means that anyone can join and intervene in it and that it has a high rigor.

So, how does it impact? It impacts that (it will sound a little cheesy, but...) we can be better people, we can know more, we can have more information. It has an impact on the fact that anyone with access to the internet, of course, can benefit from its content and learn without necessarily having to go through a paywall or be registered on a platform and change data to be able to appropriate or approach the information.

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: We call OpenStreetMap the Wikipedia of maps, because a large part of its philosophy is copied or cloned from the philosophy of Wikipedia. If you imagine Wikipedia, what people do is they put encyclopedic articles. What we do in OpenStreetMap is to enter spatial data. We build a map collaboratively and this assumes that the openstreetmap.org page, which is where you could go to look at the maps, is just the tip of the iceberg. That's where OpenStreetMap is a little more diffuse and hidden, but most of the web pages, maps and spatial information that you are seeing on the Internet, most likely in its vast majority, comes from the data of the great free, open and collaborative database that is OpenStreetMap.

Many times you are reading a newspaper and you see a map and that spatial data is taken from OpenStreetMap. They are even used in agencies: in the European Union, for example, OpenStreetMap is being used. It is used in information from private companies, public administrations, individuals, etc. And, in addition, being free, it is constantly reused.

I always like to bring up projects that we have done here, in the city of Zaragoza. We have generated the entire urban pedestrian network, that is, all the pavements, the zebra crossings, the areas where you can circulate... and with this a calculation is made of how you can move around the city on foot. You can't find this information on sidewalks, crosswalks and so on on a website because it's not very lucrative, such as getting around by car, and you can take advantage of it, for example, which is what we did in some jobs that I directed at university, to be able to know how different mobility is with blind people. in a wheelchair or with a baby carriage.

4. You are telling us that these projects are open. If a citizen is listening to us right now and wants to participate in them, what should they do to participate? How can you be part of these communities?

Florencia Claes: The interesting thing about these communities is that you don't need to be formally associated or linked to them to be able to contribute. In Wikipedia you simply enter the Wikipedia page and become a user, or not, and you can edit. What is the difference between making your username or not? In that you will be able to have better access to the contributions you have made, but we do not need to be associated or registered anywhere to be able to edit Wikipedia.

If there are groups at the local or regional level related to the Wikimedia Foundation that receive grants and grants to hold meetings or activities. That's good, because you meet people with the same concerns and who are usually very enthusiastic about free knowledge. As my friends say, we are a bunch of geeks who have met and feel that we have a group of belonging in which we share and plan how to change the world.

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: In OpenStreetMap it is practically the same, that is, you can do it alone. It is true that there is a bit of a difference with respect to Wikipedia. If you go to the openstreetmap.org page, where we have all the documentation – which is wiki.OpenStreetMap.org – you can go there and you have all the documentation.

It is true that to edit in OpenStreetMap you do need a user to better track the changes that people make to the map. If it were anonymous there could be more of a problem, because it is not like the texts in Wikipedia. But as Florencia said, it's much better if you associate yourself with a community.

We have local groups in different places. One of the initiatives that we have recently reactivated is the OpenStreetMap Spain association, in which, as Florencia said, we are a group of those who like data and free tools, and there we share all our knowledge. A lot of people come up to us and say "hey, I just entered OpenStreetMap, I like this project, how can I do this? How can I do the other?"And well, it's always much better to do it with other colleagues than to do it alone. But anyone can do it.

5. What challenges have you encountered when implementing these collaborative projects and ensuring their sustainability over time? What are the main challenges, both technical and social, that you face?

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: One of the problems we find in all these movements that are so horizontal and in which we have to seek consensus to know where to move forward, is that in the end it is relatively problematic to deal with a very diverse community. There is always friction, different points of view... I think this is the most problematic thing. What happens is that, deep down, as we are all moved by enthusiasm for the project, we end up reaching agreements that make the project grow, as can be seen in Wikimedia and OpenStreetMap themselves, which continue to grow and grow.

From a technical point of view, for some things in particular, you have to have a certain computer prowess, but we are very, very basic. For example, we have made mapathons, which consist of us meeting in an area with computers and starting to put spatial information in areas, for example, where there has been a natural disaster or something like that. Basically, on a satellite image, people place little houses where they see - little houses there in the middle of the Sahel, for example, to help NGOs such as Doctors Without Borders. That's very easy: you open it in the browser, open OpenStreetMap and right away, with four prompts, you're able to edit and contribute.

It is true that, if you want to do things that are a little more complex, you have to have more computer skills. So it is true that we always adapt. There are people who are entering data in a very pro way, including buildings, importing data from the cadastre... and there are people like a girl here in Zaragoza who recently discovered the project and is entering the data they find with an application on their mobile phone.

I do really find a certain gender bias in the project. That within OpenStreetMap worries me a little, because it is true that a large majority of the people we are editing, including the community, are men and that in the end does mean that some data has a certain bias. But hey, we're working on it.

Florencia Claes: In that sense, in the Wikimedia environment, that also happens to us. We have, more or less worldwide, 20% of women participating in the project against 80% of men and that means that, for example, in the case of Wikipedia, there is a preference for articles about footballers sometimes. It is not a preference, but simply that the people who edit have those interests and as they are more men, we have more footballers, and we miss articles related, for example, to women's health.

So we do face biases and we face that coordination of the community. Sometimes people with many years participate, new people... and achieving a balance is very important and very difficult. But the interesting thing is when we manage to keep in mind or remember that the project is above us, that we are building something, that we are giving something away, that we are participating in something very big. When we become aware of that again, the differences calm down and we focus again on the common good which, after all, I believe is the goal of these two projects, both in the Wikimedia environment and OpenStreetMap.

6. As you mentioned, both Wikimedia and OpenStreetMap are projects built by volunteers. How do you ensure data quality and accuracy?

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: The interesting thing about all this is that the community is very large and there are many eyes watching. When there is a lack of rigor in the information, both in Wikipedia – which people know more about – but also in OpenStreetMap, alarm bells go off. We have tracking systems and it's relatively easy to see dysfunctions in the data. Then we can act quickly. This gives a capacity, in OpenStreetMap in particular, to react and update the data practically immediately and to solve those problems that may arise also quite quickly. It is true that there has to be a person attentive to that place or that area.

I've always liked to talk about OpenStreetMap data as a kind of - referring to it as it is done in the software - beta map, which has the latest, but there can be some minimal errors. So, as a strongly updated and high-quality map, it can be used for many things, but for others of course not, because we have another reference cartography that is being built by the public administration.

Florencia Claes: In the Wikimedia environment we also work like this, because of the mass, because of the number of eyes that are looking at what we do and what others do. Each one, within this community, is assuming roles. There are roles that are scheduled, such as administrators or librarians, but there are others that simply: I like to patrol, so what I do is keep an eye on new articles and I could be looking at the articles that are published daily to see if they need any support, any improvement or if, on the contrary, they are so bad that they need to be removed from the main part or erased.

The key to these projects is the number of people who participate and everything is voluntary, altruistic. The passion is very high, the level of commitment is very high. So people take great care of those things. Whether data is curated to upload to Wikidata or an article is written on Wikipedia, each person who does it, does it with great affection, with great zeal. Then time goes by and he is aware of that material that he uploaded, to see how it continued to grow, if it was used, if it became richer or if, on the contrary, something was erased.

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: Regarding the quality of the data, I find interesting, for example, an initiative that the Territorial Information System of Navarre has now had. They have migrated all their data for planning and guiding emergency routes to OpenStreetMap, taking their data. They have been involved in the project, they have improved the information, but taking what was already there [in OpenStreetMap], considering that they had a high quality and that it was much more useful to them than using other alternatives, which shows the quality and importance that this project can have.

7. This data can also be used to generate open educational resources, along with other sources of knowledge. What do these resources consist of and what role do they play in the democratization of knowledge?

Florencia Claes: OER, open educational resources, should be the norm. Each teacher who generates content should make it available to citizens and should be built in modules from free resources. It would be ideal.

What role does the Wikimedia environment have in this? From housing information that can be used when building resources, to providing spaces to perform exercises or to take, for example, data and do work with SPARQL. In other words, there are different ways of approaching Wikimedia projects in relation to open educational resources. You can intervene and teach students how to identify data, how to verify sources, to simply make a critical reading of how information is presented, how it is curated, and make, for example, an assessment between languages.

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: OpenStreetMap is very similar. What's interesting and unique is what the nature of the data is. It's not exactly information in different formats like in Wikimedia. Here the information is that free spatial database that is OpenStreetMap. So the limits are the imagination.

I remember that there was a colleague who went to some conferences and made a cake with the OpenStreetMap map. He would feed it to the people and say, "See? These are maps that we have been able to eat because they are free." To make more serious or more informal or playful cartography, the limit is only your imagination. It happens exactly the same as with Wikipedia.

8. Finally, how can citizens and organizations be motivated to participate in the creation and maintenance of collaborative projects linked to free culture and open data?

Florencia Claes: I think we have to clearly do what Miguel said about the cake. You have to make a cake and invite people to eat cake. Seriously talking about what we can do to motivate citizens to reuse this data, I believe, especially from personal experience and from the groups with which I have worked on these platforms, that the interface is friendly is a very important step.

In Wikipedia in 2015, the visual editor was activated. The visual editor made us join many more women to edit Wikipedia. Before, it was edited only in code and code, because at first glance it can seem hostile or distant or "that doesn't go with me". So, to have interfaces where people don't need to have too much knowledge to know that this is a package that has such and such data and I'm going to be able to read it with such a program or I'm going to be able to dump it into such and such a thing and make it simple, friendly, attractive... I think that this is going to remove many barriers and that it will put aside the idea that data is for computer scientists. And I think that data goes further, that we can really take advantage of all of them in very different ways. So I think it's one of the barriers that we should overcome.

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: It didn't happen to us that until about 2015 (forgive me if it's not exactly the date), we had an interface that was quite horrible, almost like the code edition you have in Wikipedia, or worse, because you had to enter the data knowing the labeling, etc. It was very complex. And now we have an editor that basically you're in OpenStreetMap, you hit edit and a super simple interface comes out. You don't even have to put labeling in English anymore, it's all translated. There are many things pre-configured and people can enter the data immediately and in a very simple way. So what that has allowed is that many more people come to the project.

Another very interesting thing, which also happens in Wikipedia, although it is true that it is much more focused on the web interface, is that around OpenStreetMap an ecosystem of applications and services has been generated that has made it possible, for example, to appear mobile applications that, in a very fast, very simple way, allow data to be put directly on foot on the ground. And this makes it possible for people to enter the data in a simple way.

I wanted to stress it again, although I know that we are reiterating all the time in the same circumstance, but I think it is important to comment on it, because I think that we forget that within the projects: we need people to be aware again that data is free, that it belongs to the community, that it is not in the hands of a private company, that it can be modified, that it can be transformed, that behind it there is a community of voluntary, free people, but that this does not detract from the quality of the data, and that it reaches everywhere. So that people come closer and don't see us as a weirdo. I think that Wikipedia is much more integrated into society's knowledge and now with artificial intelligence much more, but it happens to us in OpenStreetMap, that they look at you like saying "but what are you telling me if I use another application on my mobile?" or you're using ours, you're using OpenStreetMap data without knowing it. So we need to get closer to society, to get them to know us better.

Returning to the issue of association, that is one of our objectives, that people know us, that they know that this data is open, that it can be transformed, that they can use it and that they are free to have it to build, as I said before, what they want and the limit is their imagination.

Florencia Claes: I think we should somehow integrate through gamification, through games in the classroom, the incorporation of maps, of data within the classroom, within the day-to-day schooling. I think we would have a point in our favour there. Given that we are within a free ecosystem, we can integrate visualization or reuse tools on the same pages of the data repositories that I think would make everything much friendlier and give a certain power to citizens, it would empower them in such a way that they would be encouraged to use them.

Miguel Sevilla-Callejo: It's interesting that we have things that connect both projects (we also sometimes forget the people of OpenStreetMap and Wikipedia), that there is data that we can exchange, coordinate and add. And that would also add to what you just said.

Subscribe to our Spotify profile to keep up to date with our podcasts

Interview clips

1. What is OpenStreetMap?

2. How does Wikimedia help in the creation of Open Educational Resources?

AI systems designed to assist us from the first dives to the final bibliography.

One of the missions of contemporary artificial intelligence is to help us find, sort and digest information, especially with the help of large language models. These systems have come at a time when we most need to manage knowledge that we produce and share en masse, but then struggle to embrace and consume. Its value lies in finding the ideas and data we need quickly, so that we can devote our effort and time to thinking or, in other words, start climbing the ladder a rung or two ahead.

AI-based systems academic research as well as trend studies in the business world. AI analytics tools can analyse thousands of papers to show us which authors collaborate with each other or how topics are grouped, creating an interactive, filterable map of the literature on demand. The Generative AI,the long-awaited one, can start from a research question and return useful sub-content as a synthesis or a contrast of approaches. The first shows us the terrain on the map, while the second suggests where we can move forward.

Practical tools

Starting with the more analytical ones and leaving the mixed or generative ones for last, we go through four practical research tools that integrate AI as a functionality, and one extra ball.

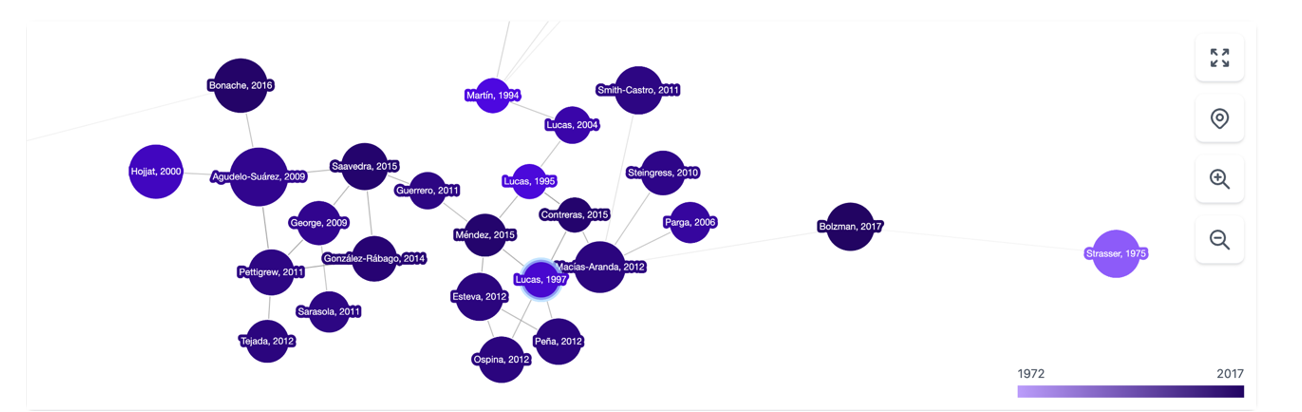

It is a tool based above all on the connection between authors, topics and articles, which shows us networks of citations and allows us to create the complete graph of the literature around a topic. As a starting point, Inciteful asks for the title or URL of a paper, but you can also simply search by your research topic. There is also the possibility to enter the data of two items, to show how they are connected to each other.

Figure 1. Screenshot in Inciteful: initial search screen and connection between papers.

Figure 2. Screenshot on Inciteful: network of nodes with articles and authors.

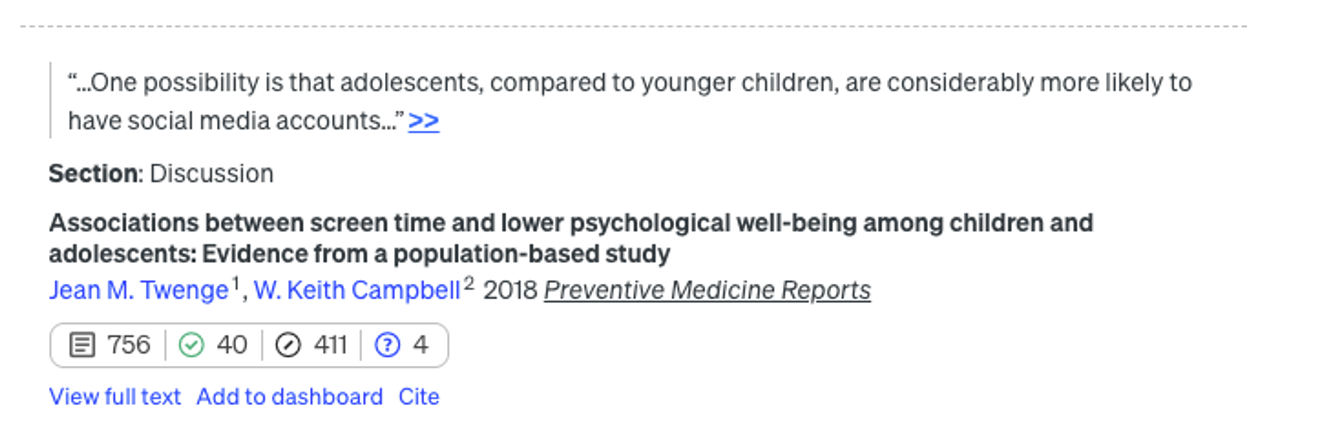

In Scite, AI integration is more obvious and practical: given a question, it creates a single summary answer by combining information from all references. The tool analyses the semantics of the papers to extract the nature of each quote: how many quotes support it ( check symbol), question it (question mark) or just mention it (slash). This allows us to do something as valuable as adding context to the impact metrics of an article in our bibliography.

Figure 3. Screenshot in Scite: initial search screen.

Figure 4. Screenshot in Scite: citation assessment of an article.

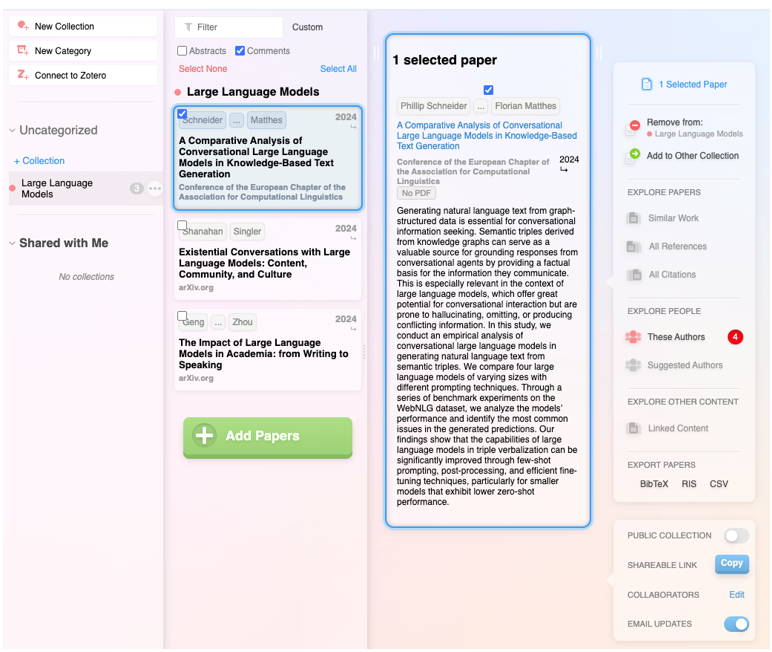

In addition to integrating the functionalities of the previous ones, it is a very complete digital product that not only allows you to navigate from paper to paper in the form of a visual network, but also makes it possible to set up alerts on a topic or an author you follow and create lists of papers. In addition, the system itself suggests which other papers you might be interested in, all in the style of a recommendation system like Spotify or Netflix. It also allows you to make public lists, as in Google Maps, and to work collaboratively with other users.

Figure 5. Screenshot on Research Rabbit: customised list of items.

It has the backing of the British government, Stanford University and NASA, and is based entirely on generative AI. Its flagship functionality is the ability to ask direct questions to a paper or a collection of articles, and finally get a targeted report with all the references. But actually, the most striking feature is the ability to improve the user's initial question: the tool instantly evaluates the quality of the question and makes suggestions to make it more accurate or interesting.

Figure 6. Screenshot in Elicit: suggestions for improvement for the initial question..

Extra ball: Consensus.

What started as a humble customised GPT within the Plus version of ChatGPT has turned into a full-fledged digital research product. Based on a question, attempt to synthesise the scientific consensus on that topic, indicating whether there is agreement or disagreement between studies. In a simple and visual way it shows how many support a statement, how many doubt it and which conclusions predominate, as well as providing a short report for quick guidance.

Figure 7. Screenshot on Consensus: impact metrics from a question

The depth button

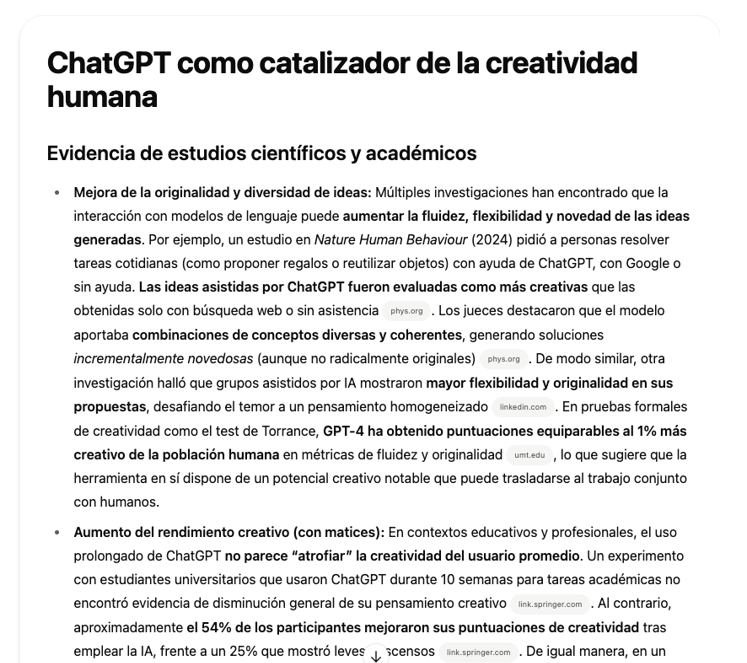

In recent months, a new functionality has appeared on the platforms of large commercial language models focused on in-depth research. Specifically, it is a button with the same name, "in-depth research" or "deep research", which can already be found in ChatGPT, Plus version (with limited requests) or Pro, and in Gemini Advanced, although they promise that it will gradually be opened to free use and allow some tests without cost.

Figure 8. Screenshot in ChatGPT Plus: In-depth research button.

Figure 9. Screenshot in Gemini Advanced: Deep Research button.

This option, which must be activated before launching the prompt, works as a shortcut: the model generates a synthetic and organised report on the topic, gathering key information, data and context. Before starting the investigation, the system may ask additional questions to better focus the search.

Figure 10. Screenshot in ChatGPT Plus: questions to narrow down the research

It should be noted that, once these questions have been answered, the system initiates a process that may take much longer than a normal response. In particular, in ChatGPT Plus it can take up to 10 minutes. A progress bar indicates progress.

Figure 11. Screenshot in ChatGPT Plus: Research start and progress bar

What we get now is a comprehensive, considerably accurate report, including examples and links that can quickly put us on the track of what we are looking for.

Figure 12: Screenshot of ChatGPT Plus: research result (excerpt).

Closure

The tools designed to apply AI for research are neither infallible nor definitive, and may still be subject to errors and hallucinations, but research with AI is already a radically different process from research without it. Assisted search is, like almost everything else when it comes to AI, about not dismissing as imperfect what can be useful, spending some time trying out new uses that can save us many hours later on, and focusing on what it can do to keep our focus on the next steps.

Content prepared by Carmen Torrijos, expert in AI applied to language and communication. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Open knowledge is knowledge that can be reused, shared and improved by other users and researchers without noticeable restrictions. This includes data, academic publications, software and other available resources. To explore this topic in more depth, we have representatives from two institutions whose aim is to promote scientific production and make it available in open access for reuse:

- Mireia Alcalá Ponce de León, Information Resources Technician of the Learning, Research and Open Science Area of the Consortium of University Services of Catalonia (CSUC).

- Juan Corrales Corrillero, Manager of the data repository of the Madroño Consortium.

Listen to the full podcast (only available in Spanish)

Summary / Transcript of the interview

1. Can you briefly explain what the institutions you work for do?

Mireia Alcalá: The CSUC is the Consortium of University Services of Catalonia and is an organisation that aims to help universities and research centres located in Catalonia to improve their efficiency through collaborative projects. We are talking about some 12 universities and almost 50 research centres.

We offer services in many areas: scientific computing, e-government, repositories, cloud administration, etc. and we also offer library and open science services, which is what we are closest to. In the area of learning, research and open science, which is where I am working, what we do is try to facilitate the adoption of new methodologies by the university and research system, especially in open science, and we give support to data management research.

Juan Corrales: The Consorcio Madroño is a consortium of university libraries of the Community of Madrid and the UNED (National University of Distance Education) for library cooperation.. We seek to increase the scientific output of the universities that are part of the consortium and also to increase collaboration between the libraries in other areas. We are also, like CSUC, very involved in open science: in promoting open science, in providing infrastructures that facilitate it, not only for the members of the Madroño Consortium, but also globally. Apart from that, we also provide other library services and create structures for them.

2. What are the requirements for an investigation to be considered open?

Juan Corrales: For research to be considered open there are many definitions, but perhaps one of the most important is given by the National Open Science Strategy, which has six pillars.

One of them is that it is necessary to put in open access both research data and publications, protocols, methodologies.... In other words, everything must be accessible and, in principle, without barriers for everyone, not only for scientists, not only for universities that can pay for access to these research data or publications. It is also important to use open source platforms that we can customise. Open source is software that anyone, in principle with knowledge, can modify, customise and redistribute, in contrast to the proprietary software of many companies, which does not allow all these things. Another important point, although this is still far from being achieved in most institutions, is allowing open peer review, because it allows us to know who has done a review, with what comments, etc. It can be said that it allows the peer review cycle to be redone and improved. A final point is citizen science: allowing ordinary citizens to be part of science, not only within universities or research institutes.

And another important point is adding new ways of measuring the quality of science.

Mireia Alcalá: I agree with what Juan says. I would also like to add that, for an investigation process to be considered open, we have to look at it globally. That is, include the entire data lifecycle. We cannot talk about a science being open if we only look at whether the data at the end is open. Already at the beginning of the whole data lifecycle, it is important to use platforms and work in a more open and collaborative way.

3. Why is it important for universities and research centres to make their studies and data available to the public?

Mireia Alcalá: I think it is key that universities and centres share their studies, because a large part of research, both here in Spain and at European and world level, is funded with public money. Therefore, if society is paying for the research, it is only logical that it should also benefit from its results. In addition, opening up the research process can help make it more transparent, more accountable, etc. Much of the research done to date has been found to be neither reusable nor reproducible. What does this mean? That the studies that have been done, almost 80% of the time someone else can't take it and reuse that data. Why? Because they don't follow the same standards, the same mannersand so on. So, I think we have to make it extensive everywhere and a clear example is in times of pandemics. With COVID-19, researchers from all over the world worked together, sharing data and findings in real time, working in the same way, and science was seen to be much faster and more efficient.

Juan Corrales: The key points have already been touched upon by Mireia. Besides, it could be added that bringing science closer to society can make all citizens feel that science is something that belongs to us, not just to scientists or academics. It is something we can participate in and this can also help to perhaps stop hoaxes, fake news, to have a more exhaustive vision of the news that reaches us through social networks and to be able to filter out what may be real and what may be false.

4.What research should be published openly?

Juan Corrales: Right now, according to the law we have in Spain, the latest Law of science, all publications that are mainly financed by public funds or in which public institutions participatemust be published in open access. This has not really had much repercussion until last year, because, although the law came out two years ago, the previous law also said so, there is also a law of the Community of Madrid that says the same thing.... but since last year it is being taken into account in the evaluation that the ANECA (the Quality Evaluation Agency) does on researchers.. Since then, almost all researchers have made it a priority to publish their data and research openly. Above all, data was something that had not been done until now.

Mireia Alcalá: At the state level it is as Juan says. We at the regional level also have a law from 2022, the Law of science, which basically says exactly the same as the Spanish law. But I also like people to know that we have to take into account not only the state legislation, but also the calls for proposals from where the money to fund the projects comes from. Basically in Europe, in framework programmes such as Horizon Europe, it is clearly stated that, if you receive funding from the European Commission, you will have to make a data management plan at the beginning of your research and publish the data following the FAIR principles.

5. Among other issues, both CSUC and Consorcio Madroño are in charge of supporting entities and researchers who want to make their data available to the public. How should a process of opening research data be? What are the most common challenges and how do you solve them?

Mireia Alcalá: In our repository, which is called RDR (from Repositori de Dades de Recerca), it is basically the participating institutions that are in charge of supporting the research staff.. The researcher arrives at the repository when he/she is already in the final phase of the research and needs to publish the data yesterday, and then everything is much more complex and time consuming. It takes longer to verify this data and make it findable, accessible, interoperable and reusable.

In our particular case, we have a checklist that we require every dataset to comply with to ensure this minimum data quality, so that it can be reused. We are talking about having persistent identifiers such as ORCID for the researcher or ROR to identify the institutions, having documentation explaining how to reuse that data, having a licence, and so on. Because we have this checklist, researchers, as they deposit, improve their processes and start to work and improve the quality of the data from the beginning. It is a slow process. The main challenge, I think, is that the researcher assumes that what he has is data, because most of them don't know it. Most researchers think of data as numbers from a machine that measures air quality, and are unaware that data can be a photograph, a film from an archaeological excavation, a sound captured in a certain atmosphere, and so on. Therefore, the main challenge is for everyone to understand what data is and that their data can be valuable to others.

And how do we solve it? Trying to do a lot of training, a lot of awareness raising. In recent years, the Consortium has worked to train data curation staff, who are dedicated to helping researchers directly refine this data. We are also starting to raise awareness directly with researchers so that they use the tools and understand this new paradigm of data management.

Juan Corrales: In the Madroño Consortium, until November, the only way to open data was for researchers to pass a form with the data and its metadata to the librarians, and it was the librarians who uploaded it to ensure that it was FAIR. Since November, we also allow researchers to upload data directly to the repository, but it is not published until it has been reviewed by expert librarians, who verify that the data and metadata are of high quality. It is very important that the data is well described so that it can be easily found, reusable and identifiable.

As for the challenges, there are all those mentioned by Mireia - that researchers often do not know they have data - and also, although ANECA has helped a lot with the new obligations to publish research data, many researchers want to put their data running in the repositories, without taking into account that they have to be quality data, that it is not enough to put them there, but that it is important that these data can be reused later.

6. What activities and tools do you or similar institutions provide to help organisations succeed in this task?

Juan Corrales: From Consorcio Madroño, the repository itself that we use, the tool where the research data is uploaded, makes it easy to make the data FAIR, because it already provides unique identifiers, fairly comprehensive metadata templates that can be customised, and so on. We also have another tool that helps create the data management plans for researchers, so that before they create their research data, they start planning how they're going to work with it. This is very important and has been promoted by European institutions for a long time, as well as by the Science Act and the National Open Science Strategy.

Then, more than the tools, the review by expert librarians is also very important. There are other tools that help assess the quality of adataset, of research data, such as Fair EVA or F-Uji, but what we have found is that those tools at the end what they are evaluating more is the quality of the repository, of the software that is being used, and of the requirements that you are asking the researchers to upload this metadata, because all our datasets have a pretty high and quite similar evaluation. So what those tools do help us with is to improve both the requirements that we're putting on our datasets, on our datasets, and to be able to improve the tools that we have, in this case the Dataverse software, which is the one we are using.

Mireia Alcalá: At the level of tools and activities we are on a par, because we have had a relationship with the Madroño Consortium for years, and just like them we have all these tools that help and facilitate putting the data in the best possible way right from the start, for example, with the tool for making data management plans. Here at CSUC we have also been working very intensively in recent years to close this gap in the data life cycle, covering issues of infrastructures, storage, cloud, etc. so that, when the data is analysed and managed, researchers also have a place to go. After the repository, we move on to all the channels and portals that make it possible to disseminate and make all this science visible, because it doesn't make sense for us to make repositories and they are there in a silo, but they have to be interconnected. For many years now, a lot of work has been done on making interoperability protocols and following the same standards. Therefore, data has to be available elsewhere, and both Consorcio Madroño and we are everywhere possible and more.

7. Can you tell us a bit more about these repositories you offer? In addition to helping researchers to make their data available to the public, you also offer a space, a digital repository where this data can be housed, so that it can be located by users.

Mireia Alcalá: If we are talking specifically about research data, as we and Consorcio Madroño have the same repository, we are going to let Juan explain the software and specifications, and I am going to focus on other repositories of scientific production that CSUC also offers. Here what we do is coordinate different cooperative repositories according to the type of resource they contain. So, we have TDX for thesis, RECERCAT for research papers, RACO for scientific journals or MACO, for open access monographs. Depending on the type of product, we have a specific repository, because not everything can be in the same place, as each output of the research has different particularities. Apart from the repositories, which are cooperative, we also have other spaces that we make for specific institutions, either with a more standard solution or some more customised functionalities. But basically it is this: we have for each type of output that there is in the research, a specific repository that adapts to each of the particularities of these formats.

Juan Corrales: In the case of Consorcio Madroño, our repository is called e-scienceData, but it is based on the same software as the CSUC repository, which is Dataverse.. It is open source software, so it can be improved and customised. Although in principle the development is managed from Harvard University in the United States, institutions from all over the world are participating in its development - I don't know if thirty-odd countries have already participated in its development.

Among other things, for example, the translations into Catalan have been done by CSUC, the translation into Spanish has been done by Consorcio Madroño and we have also participated in other small developments. The advantage of this software is that it makes it much easier for the data to be FAIR and compatible with other points that have much more visibility, because, for example, the CSUC is much larger, but in the Madroño Consortium there are six universities, and it is rare that someone goes to look for a dataset in the Madroño Consortium, in e-scienceData, directly. They usually search for it via Google or a European or international portal. With these facilities that Dataverse has, they can search for it from anywhere and they can end up finding the data that we have at Consorcio Madroño or at CSUC.

8. What other platforms with open research data, at Spanish or European level, do you recommend?

Juan Corrales: For example, at the Spanish level there is the FECYT, the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology, which has a box that collects the research data of all Spanish institutions practically. All the publications of all the institutions appear there: Consorcio Madroño, CSUC and many more.

Then, specifically for research data, there is a lot of research that should be put in a thematic repository, because that's where researchers in that branch of science are going to look. We have a tool to help choose the thematic repository. At the European level there is Zenodo, which has a lot of visibility, but does not have the data quality support of CSUC or the Madroño Consortium. And that is something that is very noticeable in terms of reuse afterwards.

Mireia Alcalá: At the national level, apart from Consorcio Madroño's and our own initiatives, data repositories are not yet widespread. We are aware of some initiatives under development, but it is still too early to see their results. However, I do know of some universities that have adapted their institutional repositories so that they can also add data. And while this is a valid solution for those who have no other choice, it has been found that software used in repositories that are not designed to handle the particularities of the data - such as heterogeneity, format, diversity, large size, etc. - are a bit lame. Then, as Juan said, at the European level, it is established that Zenodo is the multidisciplinary and multiformat repository, which was born as a result of a European project of the Commission. I agree with him that, as it is a self-archiving and self-publishing repository - that is, I Mireia Alcalá can go there in five minutes, put any document I have there, nobody has looked at it, I put the minimum metadata they ask me for and I publish it -, it is clear that the quality is very variable. There are some things that are really usable and perfect, but there are others that need a little more TLC. As Juan said, also at the disciplinary level it is important to highlight that, in all those areas that have a disciplinary repository, researchers have to go there, because that is where they will be able to use their most appropriate metadata, where everybody will work in the same way, where everybody will know where to look for those data.... For anyone who is interested there is a directory called re3data, which is basically a directory of all these multidisciplinary and disciplinary repositories. It is therefore a good place for anyone who is interested and does not know what is in their discipline. Let him go there, he is a good resource.

9. What actions do you consider to be priorities for public institutions in order to promote open knowledge?

Mireia Alcalá: What I would basically say is that public institutions should focus on making and establishing clear policies on open science, because it is true that we have come a long way in recent years, but there are times when researchers are a bit bewildered. And apart from policies, it is above all offering incentives to the entire research community, because there are many people who are making the effort to change their way of working to become immersed in open science and sometimes they don't see how all that extra effort they are making to change their way of working to do it this way pays off. So I would say this: policies and incentives.

Juan Corrales: From my point of view, the theoretical policies that we already have at the national level, at the regional level, are usually quite correct, quite good. The problem is that often no attempt has been made to enforce them. So far, from what we have seen for example with ANECA - which has promoted the use of data repositories or research article repositories - they have not really started to be used on a massive scale. In other words, incentives are necessary, and not just a matter of obligation. As Mireia has also said, we have to convince researchers to see open publishing as theirs, as it is something that benefits both them and society as a whole. What I think is most important is that: the awareness of researchers

Suscribe to our Spotify profile

Interview clips

1. Why should universities and researchers share their studies in open formats?

2. What requirements must an investigation meet in order to be considered open?

Citizen science is consolidating itself as one of the most relevant sources of most relevant sources of reference in contemporary research contemporary research. This is recognised by the Centro Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (CSIC), which defines citizen science as a methodology and a means for the promotion of scientific culture in which science and citizen participation strategies converge.

We talked some time ago about the importance importance of citizen science in society in society. Today, citizen science projects have not only increased in number, diversity and complexity, but have also driven a significant process of reflection on how citizens can actively contribute to the generation of data and knowledge.

To reach this point, programmes such as Horizon 2020, which explicitly recognised citizen participation in science, have played a key role. More specifically, the chapter "Science with and for society"gave an important boost to this type of initiatives in Europe and also in Spain. In fact, as a result of Spanish participation in this programme, as well as in parallel initiatives, Spanish projects have been increasing in size and connections with international initiatives.

This growing interest in citizen science also translates into concrete policies. An example of this is the current Spanish Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation (EECTI), for the period 2021-2027, which includes "the social and economic responsibility of R&D&I through the incorporation of citizen science" which includes "the social and economic responsibility of I through the incorporation of citizen science".

In short, we commented some time agoin short, citizen science initiatives seek to encourage a more democratic sciencethat responds to the interests of all citizens and generates information that can be reused for the benefit of society. Here are some examples of citizen science projects that help collect data whose reuse can have a positive impact on society:

AtmOOs Academic Project: Education and citizen science on air pollution and mobility.

In this programme, Thigis developed a citizen science pilot on mobility and the environment with pupils from a school in Barcelona's Eixample district. This project, which is already replicable in other schoolsconsists of collecting data on student mobility patterns in order to analyse issues related to sustainability.

On the website of AtmOOs Academic you can visualise the results of all the editions that have been carried out annually since the 2017-2018 academic year and show information on the vehicles used by students to go to class or the emissions generated according to school stage.

WildINTEL: Research project on life monitoring in Huelva

The University of Huelva and the State Agency for Scientific Research (CSIC) are collaborating to build a wildlife monitoring system to obtain essential biodiversity variables. To do this, remote data capture photo-trapping cameras and artificial intelligence are used.

The wildINTEL project project focuses on the development of a monitoring system that is scalable and replicable, thus facilitating the efficient collection and management of biodiversity data. This system will incorporate innovative technologies to provide accurate and objective demographic estimates of populations and communities.

Through this project which started in December 2023 and will continue until December 2026, it is expected to provide tools and products to improve the management of biodiversity not only in the province of Huelva but throughout Europe.

IncluScience-Me: Citizen science in the classroom to promote scientific culture and biodiversity conservation.

This citizen science project combining education and biodiversity arises from the need to address scientific research in schools. To do this, students take on the role of a researcher to tackle a real challenge: to track and identify the mammals that live in their immediate environment to help update a distribution map and, therefore, their conservation.

IncluScience-Me was born at the University of Cordoba and, specifically, in the Research Group on Education and Biodiversity Management (Gesbio), and has been made possible thanks to the participation of the University of Castilla-La Mancha and the Research Institute for Hunting Resources of Ciudad Real (IREC), with the collaboration of the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology - Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.

The Memory of the Herd: Documentary corpus of pastoral life.

This citizen science project which has been active since July 2023, aims to gather knowledge and experiences from sheperds and retired shepherds about herd management and livestock farming.

The entity responsible for the programme is the Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social, although the Museu Etnogràfic de Ripoll, Institució Milà i Fontanals-CSIC, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Universitat Rovira i Virgili also collaborate.

Through the programme, it helps to interpret the archaeological record and contributes to the preservation of knowledge of pastoral practice. In addition, it values the experience and knowledge of older people, a work that contributes to ending the negative connotation of "old age" in a society that gives priority to "youth", i.e., that they are no longer considered passive subjects but active social subjects.

Plastic Pirates Spain: Study of plastic pollution in European rivers.

It is a citizen science project which has been carried out over the last year with young people between 12 and 18 years of age in the communities of Castilla y León and Catalonia aims to contribute to generating scientific evidence and environmental awareness about plastic waste in rivers.

To this end, groups of young people from different educational centres, associations and youth groups have taken part in sampling campaigns to collect data on the presence of waste and rubbish, mainly plastics and microplastics in riverbanks and water.

In Spain, this project has been coordinated by the BETA Technology Centre of the University of Vic - Central University of Catalonia together with the University of Burgos and the Oxygen Foundation. You can access more information on their website.

Here are some examples of citizen science projects. You can find out more at the Observatory of Citizen Science in Spain an initiative that brings together a wide range of educational resources, reports and other interesting information on citizen science and its impact in Spain. do you know of any other projects? Send it to us at dinamizacion@datos.gob.es and we can publicise it through our dissemination channels.

There are a number of data that are very valuable, but which by their nature cannot be opened to the public at large. These are confidential data which are subject to third party rights that prevent them from being made available through open platforms, but which may be essential for research that promotes advances for society as a whole, in fields such as medical diagnosis public policy evaluation, detection or prosecution of criminal offences, etc.

In order to facilitate the extraction of value from these data, in compliance with the regulations in force and the rights attached to them, researchers have been provided with researchers secure processing environments, known as safe rooms, have been made available to researchers. The aim is to enable researchers to request and subsequently use and integrate the data contained in certain databases held by organisations to carry out scientific work in the public interest

All in a controlled, secure and privacy-preserving manner . Therefore, researchers and institutions having access to the data are obliged to maintain absolute confidentiality and not to disseminate any identifiable information.

In this context, the National Statistics Institute (INE), the State Tax Administration Agency (AEAT), various Social Security bodies, the State Public Employment Service (SEPE) and the Bank of Spain have signed an agreement with the National Statistics Institute (INE) have signed an agreement to boost controlled access to this type of data. The agreement is in line with the European Union's strategy and the Data Governance Regulation, as we explained in this article. One of the advantages of this agreement is that it facilitates the cross-referencing of data from different organisations through Es_Datalab.

Es_Datalab, joint access to multiple databases

ES_DataLab is a restricted microdata laboratory for researchers developing projects for scientific and public interest purposes. Access to the microdata takes place in an environment that guarantees the confidentiality of the information, as it does not allow the direct identification of the units, coming from different databases.

To access this environment, you must make an application as described here and access will only be valid for the specified period of the research. The process is as follows:

- The researcher must be recognised as a "research entity". There is currently a register of entities (universities, research institutes, research departments of public administrations, etc.) which will be expanded as new organisations apply to join.

- Once accredited, the entity must apply for access to microdata, which requires the submission of a research proposal .

Through Es_ Datalab, it is possible to access to several microdata, collected at this link. In this sense, ES_Datalab facilitates the cross-referencing of databases of the participating institutions, maximising the value that the data can offer to the development of research.

Below are some examples of the data provided by each of the agencies, either through ES_datalab for cross-checking with other sources, or in their own secure processing environments.

The National Institute of Statistics

It currently makes available microdata relating to INE datasets, including:

- Results of surveys that collect information on the labour market insertion of university graduates, the wage structure, the active population, living conditions, health in Spain, etc.

- Statistics on various social and economic aspects, such as marriages or deaths, environmental protection activities, subsidiaries of companies abroad, etc.

- Censuses, both general population and by economic activity (e.g. agricultural census).

The INE, in turn, has its own secure own secure room which facilitates access to confidential data for statistical analysis for scientific purposes in the public interest.

State Tax Administration Agency

The microdata relating to the databases provided by the AEAT include detailed information on:

- Data on the main items contained in various forms, such as form 100, relating to the annual personal income tax return, form 576, on vehicle registrations, or form 714, on wealth tax, among others.

- Foreign trade statistics, with both total data and data segmented by sector of activity.

Also noteworthy is the contribution of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, which draws on data from the State Tax Administration Agency (Agencia Estatal de la Administración Tributaria). Linked to the Ministry of Finance, it has made available to the public a Statistics Area of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (Instituto de Estudios Fiscales) as well as its own secure room. Its databases include, for example, personal income tax samples, household panels, income panels and the Spanish sector economic database (BADESPE). The product description and data request protocol is available here here.

Social Security

The Social Security grants access to microdata referring to databases such as:

- The Continuous Sample of Working Lives (MCVL), which includes individual, current and historical data on contribution bases, affiliations (working life), pensions, cohabitants, Personal Income Tax (IRPF), etc.

- Social Security affiliates with monthly information on labour relations, by dates of registration and deregistration of companies, type of contract, collective, regime, province, etc.

- Benefits recognised in the previous year, including retirement, permanent disability, temporary disability and childbirth and childcare pensions.

- Other databases such as various budget settlements, temporary redundancy procedures (ERTE) by COVID-19, medical examinations by theSocial Marine Institute (ISM), and the medical examinations of the Social Marine Institute (ISM) or data on maritime or data on student maritime training .

The social Security secure rooms available in Madrid, Barcelona and Albacete, allow the processing of this and other protected information by offering access to a series of secure workstations with various programmes and programming languages (SAS, STATA, R, Python and LibreOffice). Remote access is also allowed through secure devices (called "bastioned devices") that are distributed to researchers.

Thanks to these data, it has been possible to carry out studies on the impact of the retirement age on mortality o the use of paternity leave in Spain.

Bank of Spain

We can also find in Es_Datalab microdata related to the Bank of Spain and databases such as:

- Company databases, containing information on individual companies, consolidated non-financial corporate groups or the structure of corporate groups.

- Macroeconomic data, such as public sector debt or loans to legal entities.

- Other data relating to sustainability indicators or the household panel.

BELab is the secure data laboratory managed by the Banco de España, offering on-site (Madrid) and remote access. Its data have enabled the development of projects on the effects of the minimum wage on Spanish companies, technology management in the textile sector and machine learning applied to credit risk, among others. You can find out about all projects here both those that have been completed and those that are still in progress.

Boosting the re-use of data through the Data Governance Regulation

All these measures are part of the harmonised approach and processes carried out in implementation of the provisions of the Data Governance Regulation (DGA) to facilitate and encourage the use for scientific research purposes of data held by public sector bodies in the public interest. Likewise, in order to encourage the re-use of specific categories of data held by public sector bodies, the Single National Information Point has been set up at datos.gob.es and managed by the Directorate General for Data.

The aim is to contribute to the advancement of scientific research in our country, while protecting the confidentiality of sensitive data. Safe Rooms are an important resource for the re-use of protected data held by the public sector. They enable controlled processing of information, preserve privacy and other data rights, while facilitating compliance with the European Data Governance Regulation.

IMPaCT, the Infrastructure for Precision Medicine associated with Science and Technology, is an innovative programme that aims to revolutionise medical care. Coordinated and funded by the Carlos III Health Institute, it aims to boost the effective deployment of personalised precision medicine.

Personalised medicine is a medical approach that recognises that each patient is unique. By analysing the genetic, physiological and lifestyle characteristics of each person, more efficient and safer tailor-made treatments with fewer side effects are developed. Access to this information is also key to making progress in prevention and early detection, as well as in research and medical advances.

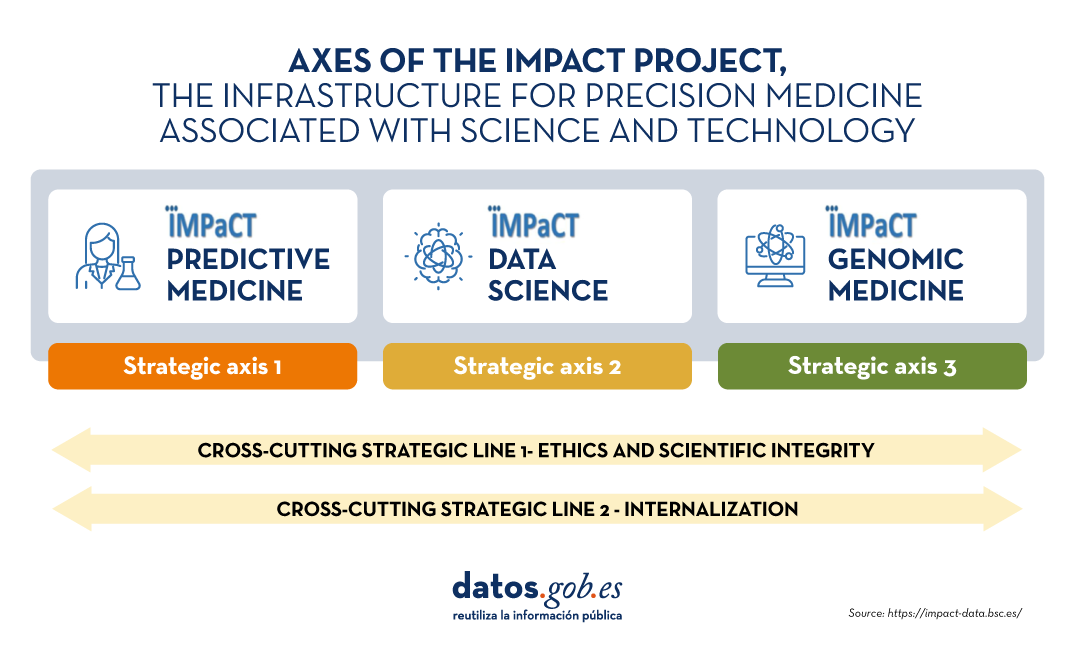

IMPaCT consists of 3 strategic axes:

- Axis 1 Predictive medicine: COHORTE Programme. It is an epidemiological research project consisting of the development and implementation of a structure for the recruitment of 200,000 people to participate in a prospective study.

- Strand 2 Data science: DATA Programme. It is a programme focused on the development of a common, interoperable and integrated system for the collection and analysis of clinical and molecular data. It develops criteria, techniques and best practices for the collection of information from electronic medical records, medical images and genomic data.

- Axis 3 Genomic medicine: GENOMICS Programme. It is a cooperative infrastructure for the diagnosis of rare and genetic diseases. Among other issues, it develops standardised procedures for the correct development of genomic analyses and the management of the data obtained, as well as for the standardisation and homogenisation of the information and criteria used.

In addition to these axes, there are two transversal strategic lines: one focused on ethics and scientific integrity and the other on internationalisation, as summarised in the following visual.

Source: IMPaCT-Data

In the following, we will focus on the functioning and results of IMPaCT-Data, the project linked to axis 2.

IMPaCT-Data, an integrated environment for interoperable data analysis

IMPaCT-Data is oriented towards the development and validation of an environment for the integration and joint analysis of clinical, molecular and genetic data, for secondary use, with the ultimate goal of facilitating the effective and coordinated implementation of personalised precision medicine in the National Health System. It is currently made up of a consortium of 45 entities associated by an agreement that runs until 31 December 2025.

Through this programme, the aim is to create a cloud infrastructure for medical data for research, as well as the necessary protocols to coordinate, integrate, manage and analyse such data. To this end, a roadmap with the following technical objectives is followed:

Source: IMPaCT-Data.

Results of IMPaCT-Data

As we can see, this infrastructure, still under development, will provide a virtual research environment for data analysis through a variety of services and products:

- IMPaCT-Data Federated Cloud. It includes access to public and access-controlled data, as well as tools and workflows for the analysis of genomic data, medical records and images. At this video shows how federated user access and job execution is realised through the use of shared computational resources. This allows for viewing and accessing the results in HTML and raw format, as well as their metadata. For those who want to go deeper into the user access options, please see this video another video where the linking of institutional accounts to the IMPaCT-Data account and the use of passports and visas for local access to protected data is shown.