At the crossroads of the 21st century, cities are facing challenges of enormous magnitude. Explosive population growth, rapid urbanization and pressure on natural resources are generating unprecedented demand for innovative solutions to build and manage more efficient, sustainable and livable urban environments.

Added to these challenges is the impact of climate change on cities. As the world experiences alterations in weather patterns, cities must adapt and transform to ensure long-term sustainability and resilience.

One of the most direct manifestations of climate change in the urban environment is the increase in temperatures. The urban heat island effect, aggravated by the concentration of buildings and asphalt surfaces that absorb and retain heat, is intensified by the global increase in temperature. Not only does this affect quality of life by increasing cooling costs and energy demand, but it can also lead to serious public health problems, such as heat stroke and the aggravation of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

The change in precipitation patterns is another of the critical effects of climate change affecting cities. Heavy rainfall episodes and more frequent and severe storms can lead to urban flooding, especially in areas with insufficient or outdated drainage infrastructure. This situation causes significant structural damage, and also disrupts daily life, affects the local economy and increases public health risks due to the spread of waterborne diseases.

In the face of these challenges, urban planning and design must evolve. Cities are adopting sustainable urban planning strategies that include the creation of green infrastructure, such as parks and green roofs, capable of mitigating the heat island effect and improving water absorption during episodes of heavy rainfall. In addition, the integration of efficient public transport systems and the promotion of non-motorised mobility are essential to reduce carbon emissions.

The challenges described also influence building regulations and building codes. New buildings must meet higher standards of energy efficiency, resistance to extreme weather conditions and reduced environmental impact. This involves the use of sustainable materials and construction techniques that not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also offer safety and durability in the face of extreme weather events.

In this context, urban digital twins have established themselves as one of the key tools to support planning, management and decision-making in cities. Its potential is wide and transversal: from the simulation of urban growth scenarios to the analysis of climate risks, the evaluation of regulatory impacts or the optimization of public services. However, beyond technological discourse and 3D visualizations, the real viability of an urban digital twin depends on a fundamental data governance issue: the availability, quality, and consistent use of standardized open data.

What do we mean by urban digital twin?

An urban digital twin is not simply a three-dimensional model of the city or an advanced visualization platform. It is a structured and dynamic digital representation of the urban environment, which integrates:

-

The geometry and semantics of the city (buildings, infrastructures, plots, public spaces).

-

Geospatial reference data (cadastre, planning, networks, environment).

-

Temporal and contextual information, which allows the evolution of the territory to be analysed and scenarios to be simulated.

-

In certain cases, updatable data streams from sensors, municipal information systems or other operational sources.

From a standards perspective, an urban digital twin can be understood as an ecosystem of interoperable data and services, where different models, scales and domains (urban planning, building, mobility, environment, energy) are connected in a coherent way. Its value lies not so much in the specific technology used as in its ability to align heterogeneous data under common, reusable and governable models.

In addition, the integration of real-time data into digital twins allows for more efficient city management in emergency situations. From natural disaster management to coordinating mass events, digital twins provide decision-makers with a real-time view of the urban situation, facilitating a rapid and coordinated response.

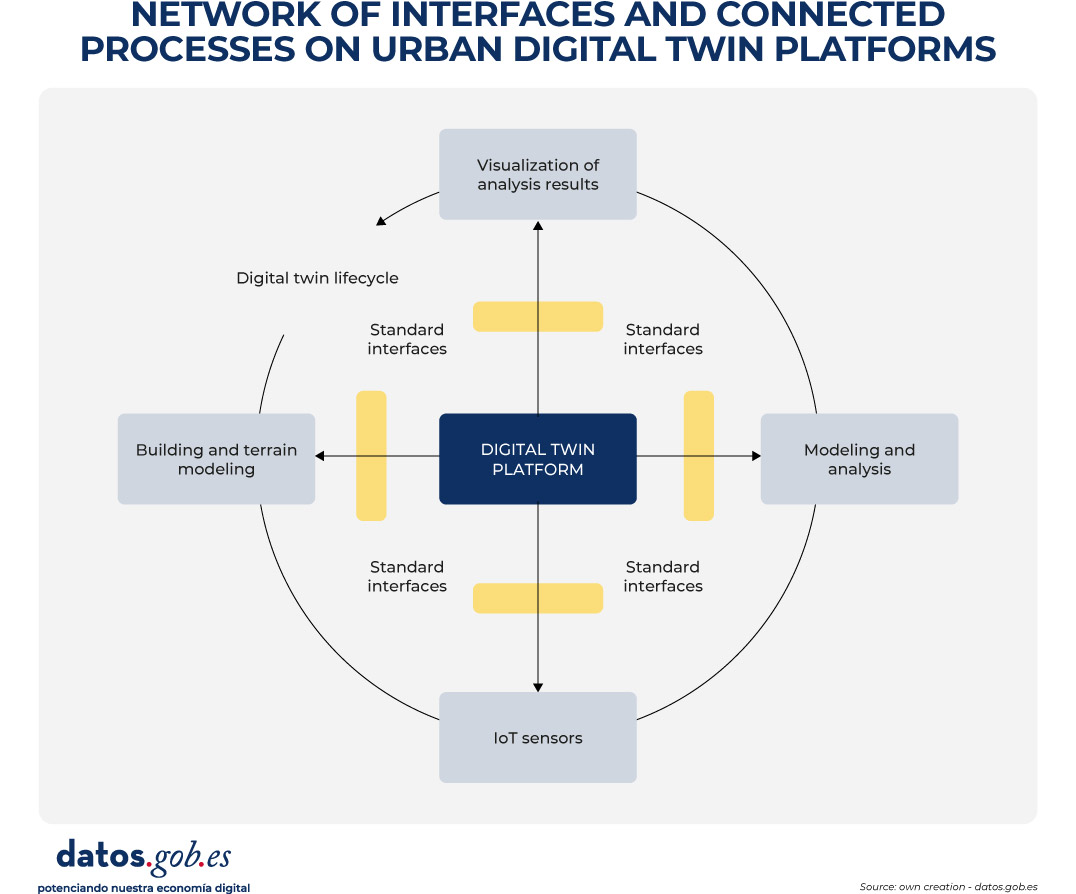

In order to contextualize the role of standards and facilitate the understanding of the inner workings of an urban digital twin, Figure 1 presents a conceptual diagram of the network of interfaces, data models, and processes that underpin it. The diagram illustrates how different sources of urban information – geospatial reference data, 3D city models, regulatory information and, in certain cases, dynamic flows – are integrated through standardised data structures and interoperable services.

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram of the network of interfaces and connected processes in urban digital twin platforms. Source: own elaboration – datos.gob.es.

In these environments, CityGML and CityJSON act as urban information models that allow the city to be digitally described in a structured and understandable way. In practice, they function as "common languages" to represent buildings, infrastructures and public spaces, not only from the point of view of their shape (geometry), but also from the point of view of their meaning (e.g. whether an object is a residential building, a public road or a green area). As a result, these models form the basis on which urban analyses and the simulation of different scenarios are based.

In order for these three-dimensional models to be visualized in an agile way in web browsers and digital applications, especially when dealing with large volumes of information, 3D Tiles can be incorporated. This standard allows urban models to be divided into manageable fragments, facilitating their progressive loading and interactive exploration, even on devices with limited capacities.

The access, exchange and reuse of all this information is usually articulated through OGC APIs, which can be understood as standardised interfaces that allow different applications to consult and combine urban data in a consistent way. These interfaces make it possible, for example, for an urban planning platform, a climate analysis tool or a citizen viewer to access the same data without the need to duplicate or transform it in a specific way.

In this way, the diagram reflects the flow of data from the original sources to the final applications, showing how the use of open standards allows for a clear separation of data, services, and use cases. This separation is key to ensuring interoperability between systems, the scalability of digital solutions and the sustainability of the urban digital twin over time, aspects that are addressed transversally in the rest of the document.

Real example: Urban regeneration project in Barcelona

An example of the impact of urban digital twins on urban construction and management can be found in the urban regeneration project of the Plaza de las Glòries Catalanes, in Barcelona (Spain). This project aimed to transform one of the city's most iconic urban areas into a more accessible, greener and sustainable public space.

Figure 2. General view. Image by the joint venture Fuses Viader + Perea + Mansilla + Desvigne.

By using digital twins from the initial phases of the project, the design and planning teams were able to create detailed digital models that represented not only the geometry of existing buildings and infrastructure, but also the complex interactions between different urban elements, such as traffic, public transport and pedestrian areas.

These models not only facilitated the visualization and communication of the proposed design among all stakeholders, but also allowed different scenarios to be simulated and their impact on mobility, air quality, and walkability to be assessed. As a result, more informed decisions could be made, contributing decisively to the overall success of the urban regeneration initiative.

The critical role of open data in urban digital twins

In the context of urban digital twins, open data should not be understood as an optional complement or as a one-off action of transparency, but as the structural basis on which sustainable, interoperable and reusable digital urban systems are built over time. An urban digital twin can only fulfil its function as a planning, analysis and decision-support tool if the data that feeds it is available, well defined and governed according to common principles.

When a digital twin develops without a clear open data strategy, it tends to become a closed system and dependent on specific technology solutions or vendors. In these scenarios, updating information is costly and complex, reuse in new contexts is limited, and the twin quickly loses its strategic value, becoming obsolete in the face of the real evolution of the city it intends to represent. This lack of openness also hinders integration with other systems and reduces the ability to adapt to new regulatory, social or environmental needs.

One of the main contributions of urban digital twins is their ability to base public decisions on traceable and verifiable data. When supported by accessible and understandable open data, these systems allow us to understand not only the outcome of a decision, but also the data, models and assumptions that support it, integrating geospatial information, urban models, regulations and, in certain cases, dynamic data. This traceability is key to accountability, the evaluation of public policies and the generation of trust at both the institutional and citizen levels. Conversely, in the absence of open data, the analyses and simulations that support urban decisions become opaque, making it difficult to explain how and why a certain conclusion has been reached and weakening confidence in the use of advanced technologies for urban management.

Urban digital twins also require the collaboration of multiple actors – administrations, companies, universities and citizens – and the integration of data from different administrative levels and sectoral domains. Without an approach based on standardized open data, this collaboration is hampered by technical and organizational barriers: each actor tends to use different formats, models, and interfaces, which increases integration costs and slows down the creation of reuse ecosystems around the digital twin.

Another significant risk associated with the absence of open data is the increase in technological dependence and the consolidation of information silos. Digital twins built on non-standardized or restricted access data are often tied to proprietary solutions, making it difficult to evolve, migrate, or integrate with other systems. From the perspective of data governance, this situation compromises the sovereignty of urban information and limits the ability of administrations to maintain control over strategic digital assets.

Conversely, when urban data is published as standardised open data, the digital twin can evolve as a public data infrastructure, shared, reusable and extensible over time. This implies not only that the data is available for consultation or visualization, but that it follows common information models, with explicit semantics, coherent geometry and well-defined access mechanisms that facilitate its integration into different systems and applications.

This approach allows the urban digital twin to act as a common database on which multiple use cases can be built —urban planning, license management, environmental assessment, climate risk analysis, mobility, or citizen participation—without duplicating efforts or creating inconsistencies. The systematic reuse of information not only optimises resources, but also guarantees coherence between the different public policies that have an impact on the territory.

From a strategic perspective, urban digital twins based on standardised open data also make it possible to align local policies with the European principles of interoperability, reuse and data sovereignty. The use of open standards and common information models facilitates the integration of digital twins into wider initiatives, such as sectoral data spaces or digitalisation and sustainability strategies promoted at European level. In this way, cities do not develop isolated solutions, but digital infrastructures coherent with higher regulatory and strategic frameworks, reinforcing the role of the digital twin as a transversal, transparent and sustainable tool for urban management.

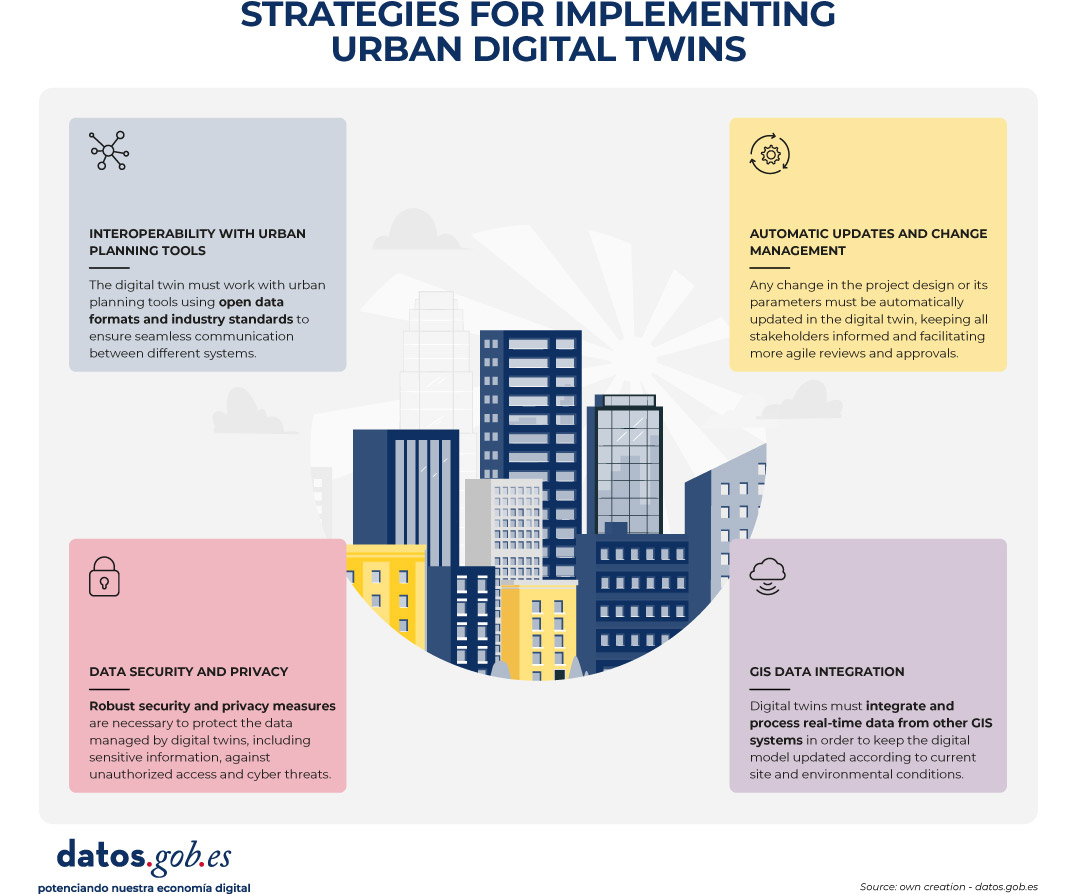

Figure 3. Strategies to implement urban digital twins. Source: own elaboration – datos.gob.es.

Conclusion

Urban digital twins represent a strategic opportunity to transform the way cities plan, manage and make decisions about their territory. However, their true value lies not in the technological sophistication of the platforms or the quality of the visualizations, but in the robustness of the data approach on which they are built.

Urban digital twins can only be consolidated as useful and sustainable tools when they are supported by standardised, well-governed open data designed from the ground up for interoperability and reuse. In the absence of these principles, digital twins risk becoming closed, difficult to maintain, poorly reusable solutions that are disconnected from the actual processes of urban governance.

The use of common information models, open standards and interoperable access mechanisms allows the digital twin to evolve as a public data infrastructure, capable of serving multiple public policies and adapting to social, environmental and regulatory changes affecting the city. This approach reinforces transparency, improves institutional coordination, and facilitates decision-making based on verifiable evidence.

In short, betting on urban digital twins based on standardised open data is not only a technical decision, but also a public policy decision in terms of data governance. It is this vision that will enable digital twins to contribute effectively to addressing major urban challenges and generating lasting public value for citizens.