In the last fifteen years we have seen how public administrations have gone from publishing their first open datasets to working with much more complex concepts. Interoperability, standards, data spaces or digital sovereignty are some of the trendy concepts. And, in parallel, the web has also changed. That open, decentralized, and interoperable space that inspired the first open data initiatives has evolved into a much more complex ecosystem, where technologies, new standards, and at the same time important challenges such as information silos to digital ethics and technological concentration coexist.

To talk about all this, today we are fortunate to have two voices that have not only observed this evolution, but have been direct protagonists of it at an international level:

- Josema Alonso, with more than twenty-five years of experience working on the open web, data and digital rights, has worked at the World Wide Web Foundation, the Open Government Partnership and the World Economic Forum, among others.

- Carlos Iglesias, an expert in web standards, open data and open government, has advised administrations around the world on more than twenty projects. He has been actively involved in communities such as W3C, the Web Foundation and the Open Knowledge Foundation.

Interview Summary / Transcript

1. At what point do you think we are now and what has changed with respect to that first stage of open data?

Carlos Iglesias: Well, I think what has changed is that we understand that today that initial battle cry of "we want the data now" is not enough. It was a first phase that at the time was very useful and necessary because we had to break with that trend of having data locked up, not sharing data. Let's say that the urgency at that time was simply to change the paradigm and that is why the battle cry was what it was. I have been involved, like Josema, in studying and analyzing all those open data portals and initiatives that arose from this movement. And I have seen that many of them began to grow without any kind of strategy. In fact, several fell by the wayside or did not have a clear vision of what they wanted to do. Simple practice I believe came to the conclusion that the publication of data alone was not enough. And from there I think that they have been proposing, a little with the maturity of the movement, that more things have to be done, and today we talk more about data governance, about opening data with a specific purpose, about the importance of metadata, models. In other words, it is no longer simply having data for the sake of having it, but there is one more vision of data as one of the most valuable elements today, probably, and also as a necessary infrastructure for many things to work today. Just as infrastructures such as road or public transport networks or energy were key in their day. Right now we are at the moment of the great explosion of artificial intelligence. A series of issues converge that have made this explode and the change is immense, despite the fact that we are only talking about perhaps a little more than ten or fifteen years since that first movement of "we want the data now". I think that right now the panorama is completely different.

Josema Alonso: Yes, it is true that we had that idea of "you publish that someone will come and do something with it". And what that did is that people began to become aware. But I, personally, could not have imagined that a few years later we would have even had a directive at European level on the publication of open data. It was something, to be honest, that we received with great pleasure. And then it will begin to be implemented in all member states. That moved consciences a little and moved practices, especially within the administration. There was a lot of fear of "let's see if I put something in there that is problematic, that is of poor quality, that I will be criticized for it", etc. But it began to generate a culture of data and the usefulness of very important data. And as Carlos also commented in recent years, I think that no one doubts this anymore. The investments that are being made, for example, at European level and in Member States, including in our country, in Spain, in the promotion and development of data spaces, are hundreds of millions of euros. Nobody has that kind of doubt anymore and now the focus is more on how to do it well, on how to get everyone to interoperate. That is, when a European data space is created for a specific sector, such as agriculture or health, all countries and organisations can share data in the best possible way, so that they can be exchanged through common models and that they are done within trusted environments.

2. In this context, why have standards become so essential?

Josema Alonso: I think it's because of everything we've learned over the years. We have learned that it is necessary for people to be able to have a certain freedom when it comes to developing their own systems. The architecture of the website itself, for example, is how it works, it does not have a central control or anything, but each participant within the website manages things in their own way. But there are clear rules of how those things then have to interact with each other, otherwise it wouldn't work, otherwise we wouldn't be able to load a web page in different browsers or on different mobile phones. So, what we are seeing lately is that there is an increasing attempt to figure out how to reach that type of consensus in a mutual benefit. For example, part of my current work for the European Commission is in the Semantic Interoperability Community, where we manage the creation of uniform models that are used across Europe, definitions of basic standard vocabularies that are used in all systems. In recent years it has also been instrumentalized in a way that supports, let's say, that consensus through regulations that have been issued, for example, at the European level. In recent years we have seen the regulation of data, the regulation of data governance and the regulation of artificial intelligence, things that also try to put a certain order and barriers. It's not that everyone goes through the middle of the mountain, because if not, in the end we won't get anywhere, but we're all going to try to do it by consensus, but we're all going to try to drive within the same road to reach the same destination together. And I think that, from the part of the public administrations, apart from regulating, it is very interesting that they are very transparent in the way it is done. It is the way in which we can all come to see that what is built is built in a certain way, the data models that are transparent, everyone can see them participate in their development. And this is where we are seeing some shortcomings in algorithmic and artificial intelligence systems, where we do not know very well the data they use or where it is hosted. And this is where perhaps we should have a little more influence in the future. But I think that as long as this duality is achieved, of generating consensus and providing a context in which people feel safe developing it, we will continue to move in the right direction.

Carlos Iglesias: If we look at the principles that made the website work in its day, there is also a lot of focus on the community part and leaving an open platform that is developed in the open, with open standards in which everyone could join. The participation of everyone was sought to enrich that ecosystem. And I think that with the data we should think that this is the way to go. In fact, it's kind of also a bit like the concept that I think is behind data spaces. In the end, it is not easy to do something like that. It's very ambitious and we don't see an invention like the web every day.

3. From your perspective, what are the real risks of data getting trapped in opaque infrastructures or models? More importantly, what can we do to prevent it?

Carlos Iglesias: Years ago we saw that there was an attempt to quantify the amount of data that was generated daily. I think that now no one even tries it, because it is on a completely different scale, and on that scale there is only one way to work, which is by automating things. And when we talk about automation, in the end what you need are standards, interoperability, trust mechanisms, etc. If we look ten or fifteen years ago, which were the companies that had the highest share price worldwide, they were companies such as Ford or General Electric. If you look at the top ten worldwide, today there are companies that we all know and use every day, such as Meta, which is the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and others, or Alphabet, which is the parent company of Google. In other words, in fact, I think I'm a little hesitant right now, but probably of the ten largest listed companies in the world, all are dedicated to data. We are talking about a gigantic ecosystem and, in order for this to really work and remain an open ecosystem from which everyone can benefit, the key is standardization.

Josema Alonso: I agree with everything Carlos said and we have to focus on not getting trapped. And above all, from the public administrations there is an essential role to play. I mentioned before about regulation, which sometimes people don't like very much because the regulatory map is starting to be extremely complicated. The European Commission, through an omnibus decree, is trying to alleviate this regulatory complexity and, as an example, in the data regulation itself, which obliges companies that have data to facilitate data portability to their users. It seems to me that it is something essential. We're going to see a lot of changes in that. There are three things that always come to mind; permanent training is needed. This changes every day at an astonishing speed. The volumes of data that are now managed are huge. As Carlos said before, a few days ago I was talking to a person who manages the infrastructure of one of the largest streaming platforms globally and he told me that they are receiving requests for data generated by artificial intelligence in such a large volume in just one week as the entire catalog they have available. So the administration needs to have permanent training on these issues of all kinds, both at the forefront of technology as we have just mentioned, and what we talked about before, how to improve interoperability, how to create better data models, etc. Another is the common infrastructure in Europe, such as the future European digital wallet, which would be the equivalent of the national citizen folder. A super simple example we are dealing with is the birth certificate. It is very complicated to try to integrate the systems of twenty-seven different countries, which in turn have regional governments and which in turn have local governments. So, the more we invest in common infrastructure, both at the semantic level and at the level of the infrastructure itself, the cloud, etc., I think the better we will do. And then the last one, which is the need for distributed but coordinated governance. Each one is governed by certain laws at local, national or European level. It is good that we begin to have more and more coordination in the higher layers and that those higher layers permeate to the lower layers and the systems are increasingly easier to integrate and understand each other. Data spaces are one of the major investments at the European level, where I believe this is beginning to be achieved. So, to summarize three things that are very practical to do: permanent training, investing in common infrastructure and that governance continues to be distributed, but increasingly coordinated.

At the crossroads of the 21st century, cities are facing challenges of enormous magnitude. Explosive population growth, rapid urbanization and pressure on natural resources are generating unprecedented demand for innovative solutions to build and manage more efficient, sustainable and livable urban environments.

Added to these challenges is the impact of climate change on cities. As the world experiences alterations in weather patterns, cities must adapt and transform to ensure long-term sustainability and resilience.

One of the most direct manifestations of climate change in the urban environment is the increase in temperatures. The urban heat island effect, aggravated by the concentration of buildings and asphalt surfaces that absorb and retain heat, is intensified by the global increase in temperature. Not only does this affect quality of life by increasing cooling costs and energy demand, but it can also lead to serious public health problems, such as heat stroke and the aggravation of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

The change in precipitation patterns is another of the critical effects of climate change affecting cities. Heavy rainfall episodes and more frequent and severe storms can lead to urban flooding, especially in areas with insufficient or outdated drainage infrastructure. This situation causes significant structural damage, and also disrupts daily life, affects the local economy and increases public health risks due to the spread of waterborne diseases.

In the face of these challenges, urban planning and design must evolve. Cities are adopting sustainable urban planning strategies that include the creation of green infrastructure, such as parks and green roofs, capable of mitigating the heat island effect and improving water absorption during episodes of heavy rainfall. In addition, the integration of efficient public transport systems and the promotion of non-motorised mobility are essential to reduce carbon emissions.

The challenges described also influence building regulations and building codes. New buildings must meet higher standards of energy efficiency, resistance to extreme weather conditions and reduced environmental impact. This involves the use of sustainable materials and construction techniques that not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also offer safety and durability in the face of extreme weather events.

In this context, urban digital twins have established themselves as one of the key tools to support planning, management and decision-making in cities. Its potential is wide and transversal: from the simulation of urban growth scenarios to the analysis of climate risks, the evaluation of regulatory impacts or the optimization of public services. However, beyond technological discourse and 3D visualizations, the real viability of an urban digital twin depends on a fundamental data governance issue: the availability, quality, and consistent use of standardized open data.

What do we mean by urban digital twin?

An urban digital twin is not simply a three-dimensional model of the city or an advanced visualization platform. It is a structured and dynamic digital representation of the urban environment, which integrates:

-

The geometry and semantics of the city (buildings, infrastructures, plots, public spaces).

-

Geospatial reference data (cadastre, planning, networks, environment).

-

Temporal and contextual information, which allows the evolution of the territory to be analysed and scenarios to be simulated.

-

In certain cases, updatable data streams from sensors, municipal information systems or other operational sources.

From a standards perspective, an urban digital twin can be understood as an ecosystem of interoperable data and services, where different models, scales and domains (urban planning, building, mobility, environment, energy) are connected in a coherent way. Its value lies not so much in the specific technology used as in its ability to align heterogeneous data under common, reusable and governable models.

In addition, the integration of real-time data into digital twins allows for more efficient city management in emergency situations. From natural disaster management to coordinating mass events, digital twins provide decision-makers with a real-time view of the urban situation, facilitating a rapid and coordinated response.

In order to contextualize the role of standards and facilitate the understanding of the inner workings of an urban digital twin, Figure 1 presents a conceptual diagram of the network of interfaces, data models, and processes that underpin it. The diagram illustrates how different sources of urban information – geospatial reference data, 3D city models, regulatory information and, in certain cases, dynamic flows – are integrated through standardised data structures and interoperable services.

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram of the network of interfaces and connected processes in urban digital twin platforms. Source: own elaboration – datos.gob.es.

In these environments, CityGML and CityJSON act as urban information models that allow the city to be digitally described in a structured and understandable way. In practice, they function as "common languages" to represent buildings, infrastructures and public spaces, not only from the point of view of their shape (geometry), but also from the point of view of their meaning (e.g. whether an object is a residential building, a public road or a green area). As a result, these models form the basis on which urban analyses and the simulation of different scenarios are based.

In order for these three-dimensional models to be visualized in an agile way in web browsers and digital applications, especially when dealing with large volumes of information, 3D Tiles can be incorporated. This standard allows urban models to be divided into manageable fragments, facilitating their progressive loading and interactive exploration, even on devices with limited capacities.

The access, exchange and reuse of all this information is usually articulated through OGC APIs, which can be understood as standardised interfaces that allow different applications to consult and combine urban data in a consistent way. These interfaces make it possible, for example, for an urban planning platform, a climate analysis tool or a citizen viewer to access the same data without the need to duplicate or transform it in a specific way.

In this way, the diagram reflects the flow of data from the original sources to the final applications, showing how the use of open standards allows for a clear separation of data, services, and use cases. This separation is key to ensuring interoperability between systems, the scalability of digital solutions and the sustainability of the urban digital twin over time, aspects that are addressed transversally in the rest of the document.

Real example: Urban regeneration project in Barcelona

An example of the impact of urban digital twins on urban construction and management can be found in the urban regeneration project of the Plaza de las Glòries Catalanes, in Barcelona (Spain). This project aimed to transform one of the city's most iconic urban areas into a more accessible, greener and sustainable public space.

Figure 2. General view. Image by the joint venture Fuses Viader + Perea + Mansilla + Desvigne.

By using digital twins from the initial phases of the project, the design and planning teams were able to create detailed digital models that represented not only the geometry of existing buildings and infrastructure, but also the complex interactions between different urban elements, such as traffic, public transport and pedestrian areas.

These models not only facilitated the visualization and communication of the proposed design among all stakeholders, but also allowed different scenarios to be simulated and their impact on mobility, air quality, and walkability to be assessed. As a result, more informed decisions could be made, contributing decisively to the overall success of the urban regeneration initiative.

The critical role of open data in urban digital twins

In the context of urban digital twins, open data should not be understood as an optional complement or as a one-off action of transparency, but as the structural basis on which sustainable, interoperable and reusable digital urban systems are built over time. An urban digital twin can only fulfil its function as a planning, analysis and decision-support tool if the data that feeds it is available, well defined and governed according to common principles.

When a digital twin develops without a clear open data strategy, it tends to become a closed system and dependent on specific technology solutions or vendors. In these scenarios, updating information is costly and complex, reuse in new contexts is limited, and the twin quickly loses its strategic value, becoming obsolete in the face of the real evolution of the city it intends to represent. This lack of openness also hinders integration with other systems and reduces the ability to adapt to new regulatory, social or environmental needs.

One of the main contributions of urban digital twins is their ability to base public decisions on traceable and verifiable data. When supported by accessible and understandable open data, these systems allow us to understand not only the outcome of a decision, but also the data, models and assumptions that support it, integrating geospatial information, urban models, regulations and, in certain cases, dynamic data. This traceability is key to accountability, the evaluation of public policies and the generation of trust at both the institutional and citizen levels. Conversely, in the absence of open data, the analyses and simulations that support urban decisions become opaque, making it difficult to explain how and why a certain conclusion has been reached and weakening confidence in the use of advanced technologies for urban management.

Urban digital twins also require the collaboration of multiple actors – administrations, companies, universities and citizens – and the integration of data from different administrative levels and sectoral domains. Without an approach based on standardized open data, this collaboration is hampered by technical and organizational barriers: each actor tends to use different formats, models, and interfaces, which increases integration costs and slows down the creation of reuse ecosystems around the digital twin.

Another significant risk associated with the absence of open data is the increase in technological dependence and the consolidation of information silos. Digital twins built on non-standardized or restricted access data are often tied to proprietary solutions, making it difficult to evolve, migrate, or integrate with other systems. From the perspective of data governance, this situation compromises the sovereignty of urban information and limits the ability of administrations to maintain control over strategic digital assets.

Conversely, when urban data is published as standardised open data, the digital twin can evolve as a public data infrastructure, shared, reusable and extensible over time. This implies not only that the data is available for consultation or visualization, but that it follows common information models, with explicit semantics, coherent geometry and well-defined access mechanisms that facilitate its integration into different systems and applications.

This approach allows the urban digital twin to act as a common database on which multiple use cases can be built —urban planning, license management, environmental assessment, climate risk analysis, mobility, or citizen participation—without duplicating efforts or creating inconsistencies. The systematic reuse of information not only optimises resources, but also guarantees coherence between the different public policies that have an impact on the territory.

From a strategic perspective, urban digital twins based on standardised open data also make it possible to align local policies with the European principles of interoperability, reuse and data sovereignty. The use of open standards and common information models facilitates the integration of digital twins into wider initiatives, such as sectoral data spaces or digitalisation and sustainability strategies promoted at European level. In this way, cities do not develop isolated solutions, but digital infrastructures coherent with higher regulatory and strategic frameworks, reinforcing the role of the digital twin as a transversal, transparent and sustainable tool for urban management.

Figure 3. Strategies to implement urban digital twins. Source: own elaboration – datos.gob.es.

Conclusion

Urban digital twins represent a strategic opportunity to transform the way cities plan, manage and make decisions about their territory. However, their true value lies not in the technological sophistication of the platforms or the quality of the visualizations, but in the robustness of the data approach on which they are built.

Urban digital twins can only be consolidated as useful and sustainable tools when they are supported by standardised, well-governed open data designed from the ground up for interoperability and reuse. In the absence of these principles, digital twins risk becoming closed, difficult to maintain, poorly reusable solutions that are disconnected from the actual processes of urban governance.

The use of common information models, open standards and interoperable access mechanisms allows the digital twin to evolve as a public data infrastructure, capable of serving multiple public policies and adapting to social, environmental and regulatory changes affecting the city. This approach reinforces transparency, improves institutional coordination, and facilitates decision-making based on verifiable evidence.

In short, betting on urban digital twins based on standardised open data is not only a technical decision, but also a public policy decision in terms of data governance. It is this vision that will enable digital twins to contribute effectively to addressing major urban challenges and generating lasting public value for citizens.

Access to data through APIs has become one of the key pieces of today's digital ecosystem. Public administrations, international organizations and private companies publish information so that third parties can reuse it in applications, analyses or artificial intelligence projects. In this situation, talking about open data is, almost inevitably, also talking about APIs.

However, access to an API is rarely completely free and unlimited. There are restrictions, controls and protection mechanisms that seek to balance two objectives that, at first glance, may seem opposite: facilitating access to data and guaranteeing the stability, security and sustainability of the service. These limitations generate frequent doubts: are they really necessary, do they go against the spirit of open data, and to what extent can they be applied without closing access?

This article discusses how these constraints are managed, why they are necessary, and how they fit – far from what is sometimes thought – within a coherent open data strategy.

Why you need to limit access to an API

An API is not simply a "faucet" of data. Behind it there is usually technological infrastructure, servers, update processes, operational costs and equipment responsible for the service working properly.

When a data service is exposed without any control, well-known problems appear:

- System saturation, caused by an excessive number of simultaneous queries.

- Abusive use, intentional or unintentional, that degrades the service for other users.

- Uncontrolled costs, especially when the infrastructure is deployed in the cloud.

- Security risks, such as automated attacks or mass scraping.

In many cases, the absence of limits does not lead to more openness, but to a progressive deterioration of the service itself.

For this reason, limiting access is not usually an ideological decision, but a practical necessity to ensure that the service is stable, predictable and fair for all users.

The API Key: basic but effective control

The most common mechanism for managing access is the API Key. While in some cases, such as the datos.gob.es National Open Data Catalog API , no key is required to access published information, other catalogs require a unique key that identifies each user or application and is included in each API call.

Although from the outside it may seem like a simple formality, the API Key fulfills several important functions. It allows you to identify who consumes the data, measure the actual use of the service, apply reasonable limits and act on problematic behavior without affecting other users.

In the Spanish context there are clear examples of open data platforms that work in this way. The State Meteorological Agency (AEMET), for example, offers open access to high-value meteorological data, but requires requesting a free API Key for automated queries. Access is free of charge, but not anonymous or uncontrolled.

So far, the approach is relatively familiar: consumer identification and basic limits of use. However, in many situations this is no longer enough.

When API becomes a strategic asset

Leading API management platforms, such as MuleSoft or Kong among others, were pioneers in implementing advanced mechanisms for controlling and protecting access to APIs. Its initial focus was on complex business environments, where multiple applications, organizations, and countries consume data services intensively and continuously.

Over time, many of these practices have also been extended to open data platforms. As certain open data services gain relevance and become key dependencies for applications, research, or business models, the challenges associated with their availability and stability become similar. The downfall or degradation of large-scale open data services—such as those related to Earth observation, climate, or science—can have a significant impact on multiple systems that depend on them.

In this sense, advanced access management is no longer an exclusively technical issue and becomes part of the very sustainability of a service that becomes strategic. It's not so much about who publishes the data, but the role that data plays within a broader ecosystem of reuse. For this reason, many open data platforms are progressively adopting mechanisms that have already been tested in other areas, adapting them to their principles of openness and public access. Some of them are detailed below.

Limiting the flow: regulating the pace, not the right of access

One of the first additional layers is the limitation of the flow of use, which is usually known as rate limiting. Instead of allowing an unlimited number of calls, it defines how many requests can be made in a given time interval.

The key here is not to prevent access, but to regulate the rhythm. A user can still use the data, but it prevents a single application from monopolizing resources. This approach is common in the Weather, Mobility, or Public Statistics APIs, where many users access it simultaneously.

More advanced platforms go a step further and apply dynamic limits, which are adjusted based on system load, time of day, or historical consumer behavior. The result is fairer and more flexible control.

Context, Origin, and Behavior: Beyond Volume

Another important evolution is to stop looking only at how many calls are made and start analyzing where and how they are made from. This includes measures such as restriction by IP addresses, geofencing, or differentiation between test and production environments.

In some cases, these limitations respond to regulatory frameworks or licenses of use. In others, they simply allow you to protect more sensitive parts of the service without shutting down general access. For example, an API can be globally accessible in query mode, but limit certain operations to very specific situations.

Platforms also analyze behavior patterns. If an application starts making repetitive, inconsistent queries or very different from its usual use, the system can react automatically: temporarily reduce the flow, launch alerts or require an additional level of validation. It is not blocked "just because", but because the behavior no longer fits with a reasonable use of the service.

Measuring impact, not just calls

A particularly relevant trend is to stop measuring only the number of requests and start considering the real impact of each one. Not all queries consume the same resources: some transfer large volumes of data or execute more expensive operations.

A clear example in open data would be an urban mobility API. Checking the status of a stop or traffic at a specific point involves little data and limited impact. On the other hand, downloading the entire vehicle position history of a city at once for several years is a much greater load on the system, even if it is done in a single call.

For this reason, many platforms introduce quotas based on the volume of data transferred, type of operation, or query weight. This avoids situations where seemingly moderate usage places a disproportionate load on the system.

How does all this fit in with open data?

At this point, the question inevitably arises: is data still open when all these layers of control exist?

The answer depends less on technology and more on the rules of the game. Open data is not defined by the total absence of technical control, but by principles such as non-discriminatory access, the absence of economic barriers, clarity in licensing, and the real possibility of reuse.

Requesting an API Key, limiting flow, or applying contextual controls does not contradict these principles if done in a transparent and equitable manner. In fact, in many cases it is the only way to guarantee that the service continues to exist and function correctly in the medium and long term.

The key is in balance: clear rules, free access, reasonable limits and mechanisms designed to protect the service, not to exclude. When this balance is achieved, control is no longer perceived as a barrier and becomes a natural part of an ecosystem of open, useful and sustainable data.

Content created by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies related to the data economy. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The Cabildo Insular de Tenerife has announced the II Open Data Contest: Development of APPs, an initiative that rewards the creation of web and mobile applications that take advantage of the datasets available on its datos.tenerife.es portal. This call represents a new opportunity for developers, entrepreneurs and innovative entities that want to transform public information into digital solutions of value for society. In this post, we tell you the details about the competition.

A growing ecosystem: from ideas to applications

This initiative is part of the Cabildo de Tenerife's Open Data project, which promotes transparency, citizen participation and the generation of economic and social value through the reuse of public information.

The Cabildo has designed a strategy in two phases:

-

The I Open Data Contest: Reuse Ideas (already held) focused on identifying creative proposals.

-

The II Contest: Development of PPPs (current call) that gives continuity to the process and seeks to materialize ideas in functional applications.

This progressive approach makes it possible to build an innovation ecosystem that accompanies participants from conceptualization to the complete development of digital solutions.

The objective is to promote the creation of digital products and services that generate social and economic impact, while identifying new opportunities for innovation and entrepreneurship in the field of open data.

Awards and financial endowment

This contest has a total endowment of 6,000 euros distributed in three prizes:

-

First prize: 3,000 euros

-

Second prize: 2,000 euros

-

Third prize: 1,000 euros

Who can participate?

The call is open to:

-

Natural persons: individual developers, designers, students, or anyone interested in the reuse of open data.

-

Legal entities: startups, technology companies, cooperatives, associations or other entities.

As long as they present the development of an application based on open data from the Cabildo de Tenerife. The same person, natural or legal, can submit as many applications as they wish, both individually and jointly.

What kind of applications can be submitted?

Proposals must be web or mobile applications that use at least one dataset from the datos.tenerife.es portal. Some ideas that can serve as inspiration are:

-

Applications to optimize transport and mobility on the island.

-

Tools for visualising tourism or environmental data.

-

Real-time citizen information services.

-

Solutions to improve accessibility and social participation.

-

Economic or demographic data analysis platforms.

Evaluation criteria: what does the jury assess?

The jury will evaluate the proposals considering the following criteria:

-

Use of open data: degree of exploitation and integration of the datasets available in the portal.

-

Impact and usefulness: value that the application brings to society, ability to solve real problems or improve existing services.

-

Innovation and creativity: originality of the proposal and innovative nature of the proposed solution.

-

Technical quality: code robustness, good programming practices, scalability and maintainability of the application.

-

Design and usability: user experience (UX), attractive and intuitive visual design, guarantee of digital accessibility on Android and iOS devices.

How to participate: deadlines and form of submission:

Applications can be submitted until March 10, 2026, three months from the publication of the call in the Official Gazette of the Province.

Regarding the required documentation, proposals must be submitted in digital format and include:

-

Detailed technical description of the application.

-

Report justifying the use of open data.

-

Specification of technological environments used.

-

Video demonstration of how the application works.

-

Complete source code.

-

Technical summary sheet.

The organising institution recommends electronic submission through the Electronic Office of the Cabildo de Tenerife, although it is also possible to submit it in person at the official registers enabled. The complete bases and the official application form are available at the Cabildo's Electronic Office.

With this second call, the Cabildo de Tenerife consolidates its commitment to transparency, the reuse of public information and the creation of a digital innovation ecosystem. Initiatives like this demonstrate how open data can become a catalyst for entrepreneurship, citizen participation, and local economic development.

In the last six months, the open data ecosystem in Spain has experienced intense activity marked by regulatory and strategic advances, the implementation of new platforms and functionalities in data portals, or the launch of innovative solutions based on public information.

In this article, we review some of those advances, so you can stay up to date. We also invite you to review the article on the news of the first half of 2025 so that you can have an overview of what has happened this year in the national data ecosystem.

Cross-cutting strategic, regulatory and policy developments

Data quality, interoperability and governance have been placed at the heart of both the national and European agenda, with initiatives seeking to foster a robust framework for harnessing the value of data as a strategic asset.

One of the main developments has been the launch of a new digital package by the European Commission in order to consolidate a robust, secure and competitive European data ecosystem. This package includes a digital bus to simplify the application of the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Regulation. In addition, it is complemented by the new Data Union Strategy, which is structured around three pillars:

- Expand access to quality data to drive artificial intelligence and innovation.

- Simplify the existing regulatory framework to reduce barriers and bureaucracy.

- Protect European digital sovereignty from external dependencies.

Its implementation will take place gradually over the next few months. It will be then that we will be able to appreciate its effects on our country and the rest of the EU territories.

Activity in Spain has also been - and will be - marked by the V Open Government Plan 2025-2029, approved last October. This plan has more than 200 initiatives and contributions from both civil society and administrations, many of them related to the opening and reuse of data. Spain's commitment to open data has also been evident in its adherence to the International Open Data Charter, a global initiative that promotes the openness and reuse of public data as tools to improve transparency, citizen participation, innovation and accountability.

Along with the promotion of data openness, work has also been done on the development of data sharing spaces. In this regard, the UNE 0087 standard was presented, which is in addition to UNE specifications on data and defines for the first time in Spain the key principles and requirements for creating and operating in data spaces, improving their interoperability and governance.

More innovative data-driven solutions

Spanish bodies continue to harness the potential of data as a driver of solutions and policies that optimise the provision of services to citizens. Some examples are:

- The Ministry of Health and citizen science initiative, Mosquito Alert, are using artificial intelligence and automated image analysis to improve real-time detection and tracking of tiger mosquitoes and invasive species.

- The Valenciaport Foundation, together with other European organisations, has launched a free tool that allows the benefits of installing wind and photovoltaic energy systems in ports to be assessed.

- The Cabildo de la Palma opted for smart agriculture with the new Smart Agro website: farmers receive personalised irrigation recommendations according to climate and location. The Cabildo has also launched a viewer to monitor mobility on the island.

- The City Council of Segovia has implemented a digital twin that centralizes high-value applications and geographic data, allowing the city to be visualized and analyzed in an interactive three-dimensional environment. It improves municipal management and promotes transparency and citizen participation.

- Vila-real City Council has launched a digital application that integrates public transport, car parks and tourist spots in real time. The project seeks to optimize urban mobility and promote sustainability through smart technology.

- Sant Boi City Council has launched an interactive map made with open data that centralises information on urban transport, parking and sustainable options on a single platform, in order to improve urban mobility.

- The DataActive International Research Network has been inaugurated, an initiative funded by the Higher Sports Council that seeks to promote the design of active urban environments through the use of open data.

Not only public bodies reuse open data, universities are also working on projects linked to digital innovation based on public information:

- Students from the Universitat de València have designed projects that use AI and open data to prevent natural disasters.

- Researchers from the University of Castilla-La Mancha have shown that it is feasible to reuse air quality prediction models in different areas of Madrid using transfer learning.

In addition to solutions, open data can also be used to shape other types of products, including sculptures. This is the case of "The skeleton of climate change", a figure presented by the National Museum of Natural Sciences, based on data on changes in global temperature from 1880 to 2024.

New portals and functionalities to extract value from data

The solutions and innovations mentioned above are possible thanks to the existence of multiple platforms for opening or sharing data that do not stop incorporating new data sets and functionalities to extract value from them. Some of the developments we have seen in this regard in recent months are:

- The National Observatory of Technology and Society (ONTSI) has launched a new website. One of its new features is Ontsi Data, a tool for preparing reports with indicators from both its portal and third parties.

- The General Council of Notaries has launched a Housing Statistical Portal, an open tool with reliable and up-to-date data on the real estate market in Spain.

- The Spanish Agency for Food Safety and Nutrition (AESAN) has inaugurated on its website an open data space with microdata on the composition of food and beverages marketed in Spain.

- The Centre for Sociological Research (CIS) launched a renewed website, adapted to any device and with a more powerful search engine to facilitate access to its studies and data.

- The National Geographic Institute (IGN) has presented a new website for SIOSE, the Information System on Land Occupation in Spain, with a more modern, intuitive and dynamic design. In addition, it has made available to the public a new version of the Geographic Reference Information of Transport Networks (IGR-RT), segmented by provinces and modes of transport, and available in Shapefile and GeoPackage.

- The AKIS Advisors Platform, promoted by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, has launched a new open data API that allows registered users to download and reuse content related to the agri-food sector in Spain.

- The Government of Catalonia launched a new corporate website that centralises key aspects of European funds, public procurement, transparency and open data in a single point. It has also launched a website where it collects information on the AI systems it uses.

- PortCastelló has published its 2024 Proceedings in open data format. All the management, traffic, infrastructures and economic data of the port are now accessible and reusable by any citizen.

- Researchers from the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya and the Institute of Photonic Sciences have created an open library with data on 140 biomolecules. A pioneering resource that promotes open science and the use of open data in biomedicine.

- CitriData, a federated space for data, models and services in the Andalusian citrus value chain, was also presented. Its goal is to transform the sector through the intelligent and collaborative use of data.

Other organizations are immersed in the development of their novelties. For example, we will soon see the new Open Data Portal of Aguas de Alicante, which will allow public access to key information on water management, promoting the development of solutions based on Big Data and AI.

These months have also seen strategic advances linked to improving the quality and use of data, such as the Data Government Model of the Generalitat Valenciana or the Roadmap for the Provincial Strategy of artificial intelligence of the Provincial Council of Castellón.

Datos.gob.es also introduced a new platform aimed at optimizing both publishing and data access. If you want to know this and other news of the Aporta Initiative in 2025, we invite you to read this post.

Encouraging the use of data through events, resources and citizen actions

The second half of 2025 was the time chosen by a large number of public bodies to launch tenders aimed at promoting the reuse of the data they publish. This was the case of the Junta de Castilla y León, the Madrid City Council, the Valencia City Council and the Provincial Council of Bizkaia. Our country has also participated in international events such as the NASA Space Apps Challenge.

Among the events where the power of open data has been disseminated, the Open Government Partnership (OGP) Global Summit, the Iberian Conference on Spatial Data Infrastructures (JIIDE), the International Congress on Transparency and Open Government or the 17th International Conference on the Reuse of Public Sector Information of ASEDIE stand out. although there were many more.

Work has also been done on reports that highlight the impact of data on specific sectors, such as the DATAGRI Chair 2025 Report of the University of Cordoba, focused on the agri-food sector. Other published documents seek to help improve data management, such as "Fundamentals of Data Governance in the context of data spaces", led by DAMA Spain, in collaboration with Gaia-X Spain.

Citizen participation is also critical to the success of data-driven innovation. In this sense, we have seen both activities aimed at promoting the publication of data and improving those already published or their reuse:

- The Barcelona Open Data Initiative requested citizen help to draw up a ranking of digital solutions based on open data to promote healthy ageing. They also organized a participatory activity to improve the iCuida app, aimed at domestic and care workers. This app allows you to search for public toilets, climate shelters and other points of interest for the day-to-day life of caregivers.

- The Spanish Space Agency launched a survey to find out the needs and uses of Earth Observation images and data within the framework of strategic projects such as the Atlantic Constellation.

In conclusion, the activities carried out in the second half of 2025 highlight the consolidation of the open data ecosystem in Spain as a driver of innovation, transparency and citizen participation. Regulatory and strategic advances, together with the creation of new platforms and solutions based on data, show a firm commitment on the part of institutions and society to take advantage of public information as a key resource for sustainable development, the improvement of services and the generation of knowledge.

As always, this article is just a small sample of the activities carried out. We invite you to share other activities that you know about through the comments.

Open data is a central piece of digital innovation around artificial intelligence as it allows, among other things, to train models or evaluate machine learning algorithms. But between "downloading a CSV from a portal" and accessing a dataset ready to apply machine learning techniques , there is still an abyss.

Much of that chasm has to do with metadata, i.e. how datasets are described (at what level of detail and by what standards). If metadata is limited to title, description, and license, the work of understanding and preparing data becomes more complex and tedious for the person designing the machine learning model. If, on the other hand, standards that facilitate interoperability are used, such as DCAT, the data becomes more FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) and, therefore, easier to reuse. However, additional metadata is needed to make the data easier to integrate into machine learning flows.

This article provides an overview of the various initiatives and standards needed to provide open data with metadata that is useful for the application of machine learning techniques.

DCAT as the backbone of open data portals

The DCAT (Data Catalog Vocabulary) vocabulary was designed by the W3C to facilitate interoperability between data catalogs published on the Web. It describes catalogs, datasets, and distributions, being the foundation on which many open data portals are built.

In Europe, DCAT is embodied in the DCAT-AP application profile, recommended by the European Commission and widely adopted to describe datasets in the public sector, for example, in Spain with DCAT-AP-ES. DCAT-AP answers questions such as:

- What datasets exist on a particular topic?

- Who publishes them, under what license and in what formats?

- Where are the download URLs or access APIs?

Using a standard like DCAT is imperative for discovering datasets, but you need to go a step further in order to understand how they are used in machine learning models or what quality they are from the perspective of these models.

MLDCAT-AP: Machine Learning in an Open Data Portal Catalog

MLDCAT-AP (Machine Learning DCAT-AP) is a DCAT application profile developed by SEMIC and the Interoperable Europe community, in collaboration with OpenML, that extends DCAT-AP to the machine learning domain.

MLDCAT-AP incorporates classes and properties to describe:

- Machine learning models and their characteristics.

- Datasets used in training and assessment.

- Quality metrics obtained on datasets.

- Publications and documentation associated with machine learning models.

- Concepts related to risk, transparency and compliance with the European regulatory context of the AI Act.

With this, a catalogue based on MLDCAT-AP no longer only responds to "what data is there", but also to:

- Which models have been trained on this dataset?

- How has that model performed by certain metrics?

- Where is this work described (scientific articles, documentation, etc.)?

MLDCAT-AP represents a breakthrough in traceability and governance, but the definition of metadata is maintained at a level that does not yet consider the internal structure of the datasets or what exactly their fields mean. To do this, it is necessary to go down to the level of the structure of the dataset distribution itself.

Metadata at the internal structure level of the dataset

When you want to describe what's inside the distributions of datasets (fields, types, constraints), an interesting initiative is Data Package, part of the Frictionless Data ecosystem.

A Data Package is defined by a JSON file that describes a set of data. This file includes not only general metadata (such as name, title, description or license) and resources (i.e. data files with their path or a URL to access their corresponding service), but also defines a schema with:

- Field names.

- Data types (integer, number, string, date, etc.).

- Constraints, such as ranges of valid values, primary and foreign keys, and so on.

From a machine learning perspective, this translates into the possibility of performing automatic structural validation before using the data. In addition, it also allows for accurate documentation of the internal structure of each dataset and easier sharing and versioning of datasets.

In short, while MLDCAT-AP indicates which datasets exist and how they fit into the realm of machine learning models, Data Package specifies exactly "what's there" within datasets.

Croissant: Metadata that prepares open data for machine learning

Even with the support of MLDCAT-AP and Data Package, it would be necessary to connect the underlying concepts in both initiatives. On the one hand, the field of machine learning (MLDCAT-AP) and on the other hand, that of the internal structures of the data itself (Data Package). In other words, the metadata of MLDCAT-AP and Data Package may be used, but in order to overcome some limitations that both suffer, it is necessary to complement it. This is where Croissant comes into play, a metadata format for preparing datasets for machine learning application. Croissant is developed within the framework of MLCommons, with the participation of industry and academia.

Specifically, Croissant is implemented in JSON-LD and built on top of schema.org/Dataset, a vocabulary for describing datasets on the Web. Croissant combines the following metadata:

- General metadata of the dataset.

- Description of resources (files, tables, etc.).

- Data structure.

- Semantic layer on machine learning (separation of training/validation/test data, target fields, etc.)

It should be noted that Croissant is designed so that different repositories (such as Kaggle, HuggingFace, etc.) can publish datasets in a format that machine learning libraries (TensorFlow, PyTorch, etc.) can load homogeneously. There is also a CKAN extension to use Croissant in open data portals.

Other complementary initiatives

It is worth briefly mentioning other interesting initiatives related to the possibility of having metadata to prepare datasets for the application of machine learning ("ML-ready datasets"):

- schema.org/Dataset: Used in web pages and repositories to describe datasets. It is the foundation on which Croissant rests and is integrated, for example, into Google's structured data guidelines to improve the localization of datasets in search engines.

- CSV on the Web (CSVW): W3C set of recommendations to accompany CSV files with JSON metadata (including data dictionaries), very aligned with the needs of tabular data documentation that is then used in machine learning.

- Datasheets for Datasets and Dataset Cards: Initiatives that enable the development of narrative and structured documentation to describe the context, provenance, and limitations of datasets. These initiatives are widely adopted on platforms such as Hugging Face.

Conclusions

There are several initiatives that help to make a suitable metadata definition for the use of machine learning with open data:

- DCAT-AP and MLDCAT-AP articulate catalog-level, machine learning models, and metrics.

- Data Package describes and validates the structure and constraints of data at the resource and field level.

- Croissant connects this metadata to the machine learning flow, describing how the datasets are concrete examples for each model.

- Initiatives such as CSVW or Dataset Cards complement the previous ones and are widely used on platforms such as HuggingFace.

These initiatives can be used in combination. In fact, if adopted together, open data is transformed from simply "downloadable files" to machine learning-ready raw material, reducing friction, improving quality, and increasing trust in AI systems built on top of it.

Jose Norberto Mazón, Professor of Computer Languages and Systems at the University of Alicante. The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The year 2025 has been a new boost for the Aporta y datos.gob.es Initiative, consolidating its role as a driver of innovation and a benchmark in the open data ecosystem in Spain. Throughout these months we have reinforced our commitment to the opening of public information, expanding resources and improving the experience of those who reuse data to generate knowledge, solutions and opportunities.

Below, and as always when the end of the year arrives, we collect some of the progress made in the last twelve months, along with the impact generated.

International momentum continues

During this year we have continued to strengthen Spain's international position in open data, participating in initiatives and forums that promote transparency and the reuse of public information at a global level. Collaboration with international organizations and alignment with European standards have allowed our country to continue to be a benchmark in the field, actively contributing to the construction of a more solid and shared data ecosystem. Some points to highlight are:

- Our country's adherence to the International Open Data Charter during the IX Global Summit of the Open Government Partnership in Vitoria-Gasteiz. With this commitment, the Government recognized data as a strategic asset to design public policies and improve services, consolidating transparency and digital innovation.

- The promotion of DCAT-AP-ES through the launch of a community on GitHub, with resources that facilitate its implementation. This new metadata model adopts the guidelines of the European DCAT-AP metadata exchange scheme, improving interoperability.

- Spain's presence, once again, among the prescribing countries in terms of open data, according to the Open Data Maturity 2025 report, prepared by data.europa.eu. Our country strengthened its leadership through the development of strategic policies, technical modernization, and innovation driven by reuse.

A new platform with more data and resources

Another of the most outstanding milestones has been the premiere of the new datos.gob.es platform, designed to optimize both publication and access to data. With a renewed look and a clearer information architecture, we have made navigation more intuitive and functional, making it easier for any user to find and take advantage of the information they need in a simpler and more efficient way.

To this must be added the growth in volume and diversity of data published on the platform. By 2025 we have reached almost 100,000 datasets available for reuse, which is an increase of 9% compared to the previous year. Among them are more than 300 high-value datasets, that is, belonging to categories "whose reuse is associated with considerable benefits for society, the environment and the economy" according to the European Union. These datasets, which are essential for strategic projects, multiply the possibilities for analysis and serve as the basis for technological innovations, for example, linked to artificial intelligence.

But the Aporta Initiative is not limited to offering data: it also accompanies the community with content that helps to understand and make the most of this information. During this year we have published more than a hundred articles on current affairs and analysis, as well as infographics, podcasts and videos that approach complex topics in a clear and accessible way. We have also expanded our guides and practical exercises, incorporating new topics such as the use of artificial intelligence in conversational applications.

The reuse of data is also reflected in the increase in use cases and business models. By 2025, dozens of innovative solutions, applications, and companies based on open data have been identified. These examples show how the openness of public information translates into tangible benefits for society and the economy.

An ever-growing community

The community that accompanies us continues to grow and consolidate. In the case of social networks, our presence on LinkedIn stands out, where we reach professionals and data experts who share and interact with our content constantly. We currently have more than 17,000 followers (23% more than in 2024). The commitment to Instagram has also been consolidated, with a growth of 95% (400 followers). Our profile on this social network was launched in 2024 and since then it has not stopped growing, attracting followers interested in the opportunities offered by the reuse of public and private data. For its part, the X (formerly Twitter) community has remained stable, at 20,700 followers.

In addition, the datos.gob.es newsletter, which has been redesigned and already has more than 4,000 subscribers, a reflection of the growing interest in staying up to date in the field of data. We have also strengthened our service channels, responding to numerous queries and requests from organisations and citizens. Specifically, nearly 2,000 interactions have been attended through the different publisher support channels, general queries and dynamization.

All this effort translates into a sustained growth of the portal: in 2025 datos.gob.es has received nearly two million visits, with more than three and a half million page views and a significant increase in the time spent by users. These figures confirm that more and more people are finding open data a valuable resource for their projects and activities.

Thank you for joining us

In summary, the balance of 2025 reflects a year of progress, learning, and shared achievements. None of this would be possible without the collaboration of the data community in Spain, which promotes the universe of open data with its participation and creativity. In 2026 we will continue to work together so that data continues to be a lever for innovation, transparency and progress.

Spain once again stands out in the European open data landscape. The Open Data Maturity 2025 report places our country among the leaders in the opening and reuse of public sector information, consolidating an upward trajectory in digital innovation.

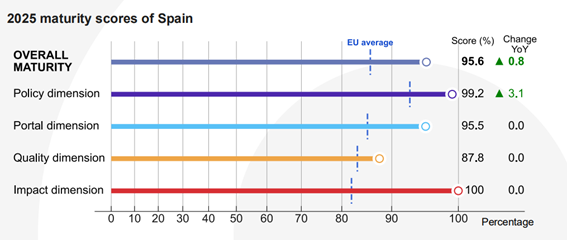

The report, produced annually by the European data portal, data.europa.eu, assesses the degree of maturity of open data in Europe. To do this, it analyzes several indicators, grouped into four dimensions: policy, portal, quality and impact. This year's edition has involved 36 countries, including the 27 Member States of the European Union (EU), three European Free Trade Association countries (Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) and six candidate countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia and Ukraine).

This year, Spain is in fifth position among the countries of the European Union and sixth out of the total number of countries analysed, tied with Italy. Specifically, a total score of 95.6% was obtained, well above the average of the countries analysed (81.1%). With this data, Spain improves its score compared to 2024, when it obtained 94.8%.

Spain, among the European leaders

With this position, Spain is once again among the countries that prescribe open data (trendsetters), i.e. those that set trends and serve as an example of good practices to other States. Spain shares a group with France, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraine, Ireland, the aforementioned Italy, Slovakia, Cyprus, Portugal, Estonia and the Czech Republic.

The countries in this group have advanced open data policies, aligned with the technical and political progress of the European Union, including the publication of high-value datasets. In addition, there is strong coordination of open data initiatives at all levels of government. Its national portals offer comprehensive features and quality metadata, with few limitations on publication or use. This means that published data can be more easily reused for multiple purposes, helping to generate a positive impact in different areas.

Figure 1. Member countries of the different clusters.

The keys to Spain's progress

According to the report, Spain strengthened its leadership in open data through strategic policy development, technical modernization, and reuse-driven innovation. In particular, improvements in the political sphere are what have boosted Spain's growth:

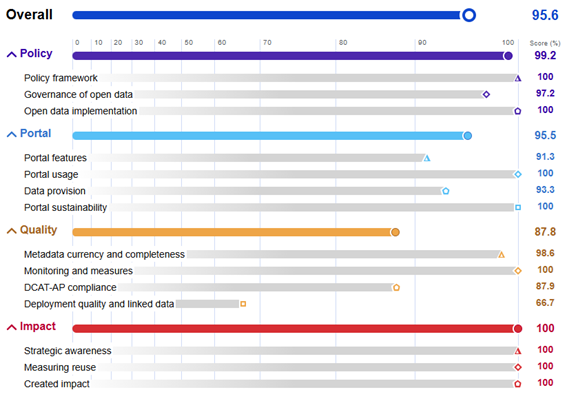

Figure 2. Spain's score in the different dimensions together with growth over the previous year.

As shown in the image, the political dimension has reached a score of 99.2% compared to 96% last year, standing out from the European average of 93.1%. The reason for this growth is the progress in the regulatory framework. In this regard, the report highlights the configuration of the V Open Government Plan, developed through a co-creation process in which all stakeholders participated. This plan has introduced new initiatives related to the governance and reuse of open data. Another noteworthy issue is that Spain promoted the publication of high-value datasets, in line with Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/138.

The rest of the dimensions remain stable, all of them with scores above the European average: in the portal dimension, 95.5% has been obtained compared to 85.45% in Europe, while the quality dimension has been valued with 87.8% compared to 83.4% in the rest of the countries analysed. The Impact block continues to be our great asset, with 100% compared to 82.1% in Europe. In this dimension, we continue to position ourselves as great leaders, thanks to a clear definition of reuse, the systematic measurement of data use and the existence of examples of impact in the governmental, social, environmental and economic spheres.

Although there have not been major movements in the score of these dimensions, the report does highlight milestones in Spain in all areas. For example, the datos.gob.es platform underwent a major redesign, including adjustments to the DCAT-AP-ES metadata profile, in order to improve quality and interoperability. In this regard, a specific implementation guide was published and a learning and development community was consolidated through GitHub. In addition, the portal's search engine and monitoring tools were improved, including tracking external reuse through GitHub references and rich analytics through interactive dashboards.

The involvement of the infomediary sector has been key in strengthening Spain's leadership in open data. The report highlights the importance of activities such as the National Open Data Meeting, with challenges that are worked on jointly by a multidisciplinary team with representatives of public, private and academic institutions, edition after edition. In addition, the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces identified 80 essential data sets on which local governments should focus when advancing in the opening of information, promoting coherence and reuse at the municipal level.

The following image shows the specific score for each of the subdimensions analyzed:

Figure 3. Spain's score in the different dimensions and subcategories.

You can see the details of the report for Spain on the website of the European portal.

Next steps and common challenges

The report concludes with a series of specific recommendations for each group of countries. For the group of trendsetters, in which Spain is located, the recommendations are not so much focused on reaching maturity – already achieved – but on deepening and expanding their role as European benchmarks. Some of the recommendations are:

- Consolidate thematic ecosystems (supplier and reuser communities) and prioritize high-value data in a systematic way.

- Align local action with the national strategy, enabling "data-driven" policies.

- Cooperate with data.europa.eu and other countries to implement and adapt an impact assessment framework with domain-by-domain metrics.

- Develop user profiles and allow their contributions to the national portal.

- Improve data and metadata quality and localization through validation tools, artificial intelligence, and user-centric flows.

- Apply domain-specific standards to harmonize datasets and maximize interoperability, quality, and reusability.

- Offer advanced and certified training in regulations and data literacy.

- Collaborate internationally on reusable solutions, such as shared or open source software.

Spain is already working on many of these points to continue improving its open data offer. The aim is for more and more reusers to be able to easily take advantage of the potential of public information to generate services and solutions that generate a positive impact on society as a whole.

The position achieved by Spain in this European ranking is the result of the work of all public initiatives, companies, user communities and reusers linked to open data, which promote an ecosystem that does not stop growing. Thank you for the effort!

In this podcast we talk about transport and mobility data, a topic that is very present in our day-to-day lives. Every time we consult an application to find out how long a bus will take, we are taking advantage of open data linked to transport. In the same way, when an administration carries out urban planning or optimises traffic flows, it makes use of mobility data.

To delve into the challenges and opportunities behind the opening of this type of data by Spanish public administrations, we have two exceptional guests:

- Tania Gullón Muñoz-Repiso, director of the Division of Transport Studies and Technology of the Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility. Welcome, Tania!

- Alicia González Jiménez, deputy director in the General Subdirectorate of Cartography and Observation of the Territory of the National Geographic Institute.

Listen here the full episode (in Spanish)

Summary / Transcript of the interview

1. Both the IGN and the Ministry generate a large amount of data related to transport. Of all of them, can you tell us which data and services are made available to the public as open data?

Alicia González: On the part of the National Geographic Institute, I would say that everything: everything we produce is available to users, because since the end of 2015 the dissemination policy adopted by the General Directorate of the National Geographic Institute, through the Autonomous Organism National Center for Geographic Information (CNIG), which is where all products and services are distributed, is an open data policy, so that everything is distributed under the CC BY 4.0 license, which protects free and open use. You simply have to make an attribution, a mention of the origin of the data. So we are talking, in general, not only about transport, but about all kinds of data, about more than 100 products that represent more than two and a half million files that users are increasingly demanding. In fact, in 2024 we have had up to 20 million files downloaded, so it is in high demand. And specifically in terms of transmission networks, the fundamental set of data is the Geographic Reference Information of Transport Networks (IGR-RT). It is a multimodal geospatial dataset that is composed of five transport networks that are continuous throughout the national territory and also interconnected. Specifically, it contemplates:

1. The road network that is made up of the entire road network, regardless of its owner and that runs throughout the territory. There are more than 300 thousand kilometers of road that are also connected to all the street maps, to the urban road network of all population centers. That is, we have a road graph that backbones the entire territory, in addition to having connected the roads that are later distributed and disseminated in the National Topographic Map.

2. The second most important network is the rail transport network. It includes all the data of rail transport and also of metro, tram and other types of modes by rail.

3 and 4. In the maritime and air field, the networks are already limited to infrastructures, so that they contain all the ports on the Spanish coast and all the infrastructures of aerodromes, airports, heliports in the air part.

5. And finally, the last network, which is much more modest, is residual data: cable transport.

Everything is interconnected through intermodal relationships. It is a set of data that is generated from official sources. We cannot incorporate just any data, it must always be official data and it is generated within the framework of cooperation of the National Cartographic System.

As a dataset that complies with the INSPIRE Directive both in its definition and in the way it is disseminated through standard web services, it has also been classified as a high-value dataset in the mobility category, in accordance with the High-Value Data Enforcement Regulation. It is a fairly important and normalized set.

How can it be located and accessed? Precisely, as it is standard, it is catalogued in the IDE (Spatial Data Infrastructure) catalogue, thanks to the standard description of its metadata. It can also be located through the official INSPIRE (Information Publication Services) data and services catalog or is accessible through portals as relevant as the open data portal.

Once we have located it, how can the user access it? How can they see the data? There are several ways. The easiest: check your visualizer. All the data is displayed there and there are certain query tools to facilitate its use. And then, of course, through the CNIG download centre. There we publish all the data from all the networks and it is in great demand. And then the last way is to consult the standard web services that we generate, visualization services and downloads of different technologies. In other words, it is a set of data that is available to users for reuse.

Tania Gullón: In the Ministry we also share a lot of open data. I would like, in order not to take too long, to comment in particular on four large sets of data:

1. The first would be the OTLE, the Observatory of Transport and Logistics in Spain, which is an initiative of the Ministry of Transport, whose main objective is to provide a global and comprehensive vision of the situation of transport and logistics in Spain. It is organized into seven blocks: mobility, socio-economy, infrastructure, security, sustainability, metropolitan transport and logistics. These are not georeferenced data, but statistical data. The Observatory makes data, graphs, maps, indicators available to the public and, not only that, but also offers annual reports, monographs, conferences, etc. And also of the observatories that we have cross-border, which are done collaboratively with Portugal and France.

2. The second set of data I want to mention is the NAP, the National Multimodal Transport Access Point, which is an official digital platform managed by the Ministry of Transport, but which is developed collaboratively between the different administrations. Its objective is to centralise and publish all the digitised information on the passenger transport offer in the national territory of all modes of transport. What do we have here? All schedules, services, routes, stops of all transport services, road transport, urban, intercity, rural, discretionary buses on demand. There are 116 datasets. The one of rail transport, the schedules of all those trains, their stops, etc. Also of maritime transport and air transport. And this data is constantly updated in real time. To date, we only have static data in GTFS (General Transit Feed Specification) format, which can also be reused and in a standard format that is useful for the further development of mobility applications by reusers. And while this NAP initially focused on static data, such as those routes, schedules, and stops, progress is being made toward incorporating dynamic data as well. In fact, in December we also have an obligation under European regulations that oblige us to have this data in real time to, in the end, improve all that transport planning and the user experience.