We live in an age where more and more phenomena in the physical world can be observed, measured, and analyzed in real time. The temperature of a crop, the air quality of a city, the state of a dam, the flow of traffic or the energy consumption of a building are no longer data that are occasionally reviewed: they are continuous flows of information that are generated second by second.

This revolution would not be possible without cyber-physical systems (CPS), a technology that integrates sensors, algorithms and actuators to connect the physical world with the digital world. But CPS does not only generate data: it can also be fed by open data, multiplying its usefulness and enabling evidence-based decisions.

In this article, we will explore what CPS is, how it generates massive data in real time, what challenges it poses to turn that data into useful public information, what principles are essential to ensure its quality and traceability, and what real-world examples demonstrate the potential for its reuse. We will close with a reflection on the impact of this combination on innovation, citizen science and the design of smarter public policies.

What are cyber-physical systems?

A cyber-physical system is a tight integration between digital components – such as software, algorithms, communication and storage – and physical components – sensors, actuators, IoT devices or industrial machines. Its main function is to observe the environment, process information and act on it.

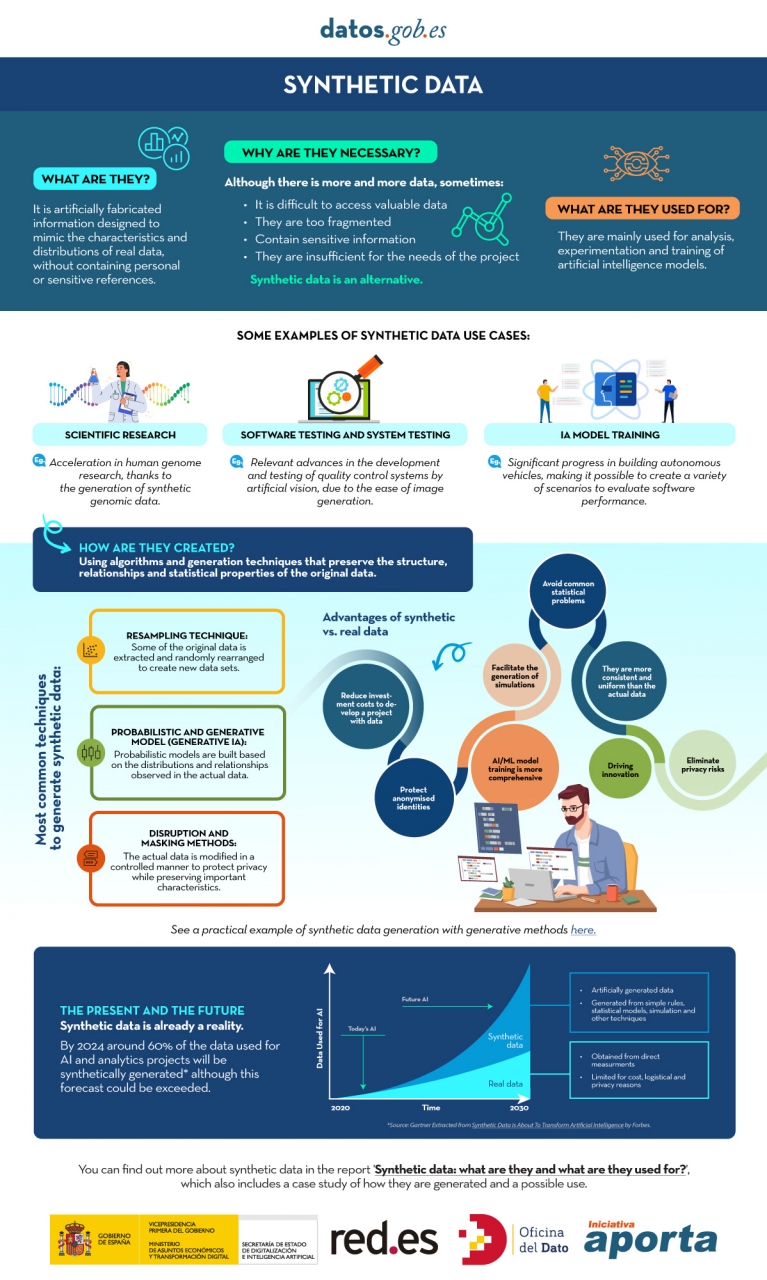

Unlike traditional monitoring systems, a CPS is not limited to measuring: it closes a complete loop between perception, decision, and action. This cycle can be understood through three main elements:

Figure 1. Cyber-physical systems cycle. Source: own elaboration

An everyday example that illustrates this complete cycle of perception, decision and action very well is smart irrigation, which is increasingly present in precision agriculture and home gardening systems. In this case, sensors distributed throughout the terrain continuously measure soil moisture, ambient temperature, and even solar radiation. All this information flows to the computing unit, which analyzes the data, compares it with previously defined thresholds or with more complex models – for example, those that estimate the evaporation of water or the water needs of each type of plant – and determines whether irrigation is really necessary.

When the system concludes that the floor has reached a critical level of dryness, the third element of CPS comes into play: the actuators. They are the ones who open the valves, activate the water pump or regulate the flow rate, and they do so for the exact time necessary to return the humidity to optimal levels. If conditions change—if it starts raining, if the temperature drops, or if the soil recovers moisture faster than expected—the system itself adjusts its behavior accordingly.

This whole process happens without human intervention, autonomously. The result is a more sustainable use of water, better cared for plants and a real-time adaptability that is only possible thanks to the integration of sensors, algorithms and actuators characteristic of cyber-physical systems.

CPS as real-time data factories

One of the most relevant characteristics of cyber-physical systems is their ability to generate data continuously, massively and with a very high temporal resolution. This constant production can be seen in many day-to-day situations:

- A hydrological station can record level and flow every minute.

- An urban mobility sensor can generate hundreds of readings per second.

- A smart meter records electricity consumption every few minutes.

- An agricultural sensor measures humidity, salinity, and solar radiation several times a day.

- A mapping drone captures decimetric GPS positions in real time.

Beyond these specific examples, the important thing is to understand what this capability means for the system as a whole: CPS become true data factories, and in many cases come to function as digital twins of the physical environment they monitor. This almost instantaneous equivalence between the real state of a river, a crop, a road or an industrial machine and its digital representation allows us to have an extremely accurate and up-to-date portrait of the physical world, practically at the same time as the phenomena occur.

This wealth of data opens up a huge field of opportunity when published as open information. Data from CPS can drive innovative services developed by companies, fuel high-impact scientific research, empower citizen science initiatives that complement institutional data, and strengthen transparency and accountability in the management of public resources.

However, for all this value to really reach citizens and the reuse community, it is necessary to overcome a series of technical, organisational and quality challenges that determine the final usefulness of open data. Below, we look at what those challenges are and why they are so important in an ecosystem that is increasingly reliant on real-time generated information.

The challenge: from raw data to useful public information

Just because a CPS generates data does not mean that it can be published directly as open data. Before reaching the public and reuse companies, the information needs prior preparation , validation, filtering and documentation. Administrations must ensure that such data is understandable, interoperable and reliable. And along the way, several challenges appear.

One of the first is standardization. Each manufacturer, sensor and system can use different formats, different sample rates or its own structures. If these differences are not harmonized, what we obtain is a mosaic that is difficult to integrate. For data to be interoperable, common models, homogeneous units, coherent structures, and shared standards are needed. Regulations such as INSPIRE or the OGC (Open Geospatial Consortium) and IoT-TS standards are key so that data generated in one city can be understood, without additional transformation, in another administration or by any reuser.

The next big challenge is quality. Sensors can fail, freeze always reporting the same value, generate physically impossible readings, suffer electromagnetic interference or be poorly calibrated for weeks without anyone noticing. If this information is published as is, without a prior review and cleaning process, the open data loses value and can even lead to errors. Validation – with automatic checks and periodic review – is therefore indispensable.

Another critical point is contextualization. An isolated piece of information is meaningless. A "12.5" says nothing if we don't know if it's degrees, liters or decibels. A measurement of "125 ppm" is useless if we do not know what substance is being measured. Even something as seemingly objective as coordinates needs a specific frame of reference. And any environmental or physical data can only be properly interpreted if it is accompanied by the date, time, exact location and conditions of capture. This is all part of metadata, which is essential for third parties to be able to reuse information unambiguously.

It's also critical to address privacy and security. Some CPS can capture information that, directly or indirectly, could be linked to sensitive people, property, or infrastructure. Before publishing the data, it is necessary to apply anonymization processes, aggregation techniques, security controls and impact assessments that guarantee that the open data does not compromise rights or expose critical information.

Finally, there are operational challenges such as refresh rate and robustness of data flow. Although CPS generates information in real time, it is not always appropriate to publish it with the same granularity: sometimes it is necessary to aggregate it, validate temporal consistency or correct values before sharing it. Similarly, for data to be useful in technical analysis or in public services, it must arrive without prolonged interruptions or duplication, which requires a stable infrastructure and monitoring mechanisms.

Quality and traceability principles needed for reliable open data

Once these challenges have been overcome, the publication of data from cyber-physical systems must be based on a series of principles of quality and traceability. Without them, information loses value and, above all, loses trust.

The first is accuracy. The data must faithfully represent the phenomenon it measures. This requires properly calibrated sensors, regular checks, removal of clearly erroneous values, and checking that readings are within physically possible ranges. A sensor that reads 200°C at a weather station or a meter that records the same consumption for 48 hours are signs of a problem that needs to be detected before publication.

The second principle is completeness. A dataset should indicate when there are missing values, time gaps, or periods when a sensor has been disconnected. Hiding these gaps can lead to wrong conclusions, especially in scientific analyses or in predictive models that depend on the continuity of the time series.

The third key element is traceability, i.e. the ability to reconstruct the history of the data. Knowing which sensor generated it, where it is installed, what transformations it has undergone, when it was captured or if it went through a cleaning process allows us to evaluate its quality and reliability. Without traceability, trust erodes and data loses value as evidence.

Proper updating is another fundamental principle. The frequency with which information is published must be adapted to the phenomenon measured. Air pollution levels may need updates every few minutes; urban traffic, every second; hydrology, every minute or every hour depending on the type of station; and meteorological data, with variable frequencies. Posting too quickly can generate noise; too slow, it can render the data useless for certain uses.

The last principle is that of rich metadata. Metadata explains the data: what it measures, how it is measured, with what unit, how accurate the sensor is, what its operating range is, where it is located, what limitations the measurement has and what this information is generated for. They are not a footnote, but the piece that allows any reuser to understand the context and reliability of the dataset. With good documentation, reuse isn't just possible: it skyrockets.

Examples: CPS that reuses public data to be smarter

In addition to generating data, many cyber-physical systems also consume public data to improve their performance. This feedback makes open data a central resource for the functioning of smart territories. When a CPS integrates information from its own sensors with external open sources, its anticipation, efficiency, and accuracy capabilities are dramatically increased.

Precision agriculture: In agriculture, sensors installed in the field allow variables such as soil moisture, temperature or solar radiation to be measured. However, smart irrigation systems do not rely solely on this local information: they also incorporate weather forecasts from AEMET, open IGN maps on slope or soil types, and climate models published as public data. By combining their own measurements with these external sources, agricultural CPS can determine much more accurately which areas of the land need water, when to plant, and how much moisture should be maintained in each crop. This fine management allows water and fertilizer savings that, in some cases, exceed 30%.

Water management: Something similar happens in water management. A cyber-physical system that controls a dam or irrigation canal needs to know not only what is happening at that moment, but also what may happen in the coming hours or days. For this reason, it integrates its own level sensors with open data on river gauging, rain and snow predictions, and even public information on ecological flows. With this expanded vision, the CPS can anticipate floods, optimize the release of the reservoir, respond better to extreme events or plan irrigation sustainably. In practice, the combination of proprietary and open data translates into safer and more efficient water management.

Impact: innovation, citizen science, and data-driven decisions

The union between cyber-physical systems and open data generates a multiplier effect that is manifested in different areas.

- Business innovation: Companies have fertile ground to develop solutions based on reliable and real-time information. From open data and CPS measurements, smarter mobility applications, water management platforms, energy analysis tools, or predictive systems for agriculture can emerge. Access to public data lowers barriers to entry and allows services to be created without the need for expensive private datasets, accelerating innovation and the emergence of new business models.

- Citizen science: the combination of SCP and open data also strengthens social participation. Neighbourhood communities, associations or environmental groups can deploy low-cost sensors to complement public data and better understand what is happening in their environment. This gives rise to initiatives that measure noise in school zones, monitor pollution levels in specific neighbourhoods, follow the evolution of biodiversity or build collaborative maps that enrich official information.

- Better public decision-making: finally, public managers benefit from this strengthened data ecosystem. The availability of reliable and up-to-date measurements makes it possible to design low-emission zones, plan urban transport more effectively, optimise irrigation networks, manage drought or flood situations or regulate energy policies based on real indicators. Without open data that complements and contextualizes the information generated by the CPS, these decisions would be less transparent and, above all, less defensible to the public.

In short, cyber-physical systems have become an essential piece of understanding and managing the world around us. Thanks to them, we can measure phenomena in real time, anticipate changes and act in a precise and automated way. But its true potential unfolds when its data is integrated into a quality open data ecosystem, capable of providing context, enriching decisions and multiplying uses.

The combination of SPC and open data allows us to move towards smarter territories, more efficient public services and more informed citizen participation. It provides economic value, drives innovation, facilitates research and improves decision-making in areas as diverse as mobility, water, energy or agriculture.

For all this to be possible, it is essential to guarantee the quality, traceability and standardization of the published data, as well as to protect privacy and ensure the robustness of information flows. When these foundations are well established, CPS not only measure the world: they help it improve, becoming a solid bridge between physical reality and shared knowledge.

Content created by Dr. Fernando Gualo, Professor at UCLM and Government and Data Quality Consultant. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Quantum computing promises to solve problems in hours that would take millennia for the world's most powerful supercomputers. From designing new drugs to optimizing more sustainable energy grids, this technology will radically transform our ability to address humanity's most complex challenges. However, its true democratizing potential will only be realized through convergence with open data, allowing researchers, companies, and governments around the world to access both quantum computing power in the cloud and the public datasets needed to train and validate quantum algorithms.

Trying to explain quantum theory has always been a challenge, even for the most brilliant minds humanity has given in the last 2 centuries. The celebrated physicist Richard Feynman (1918-1988) put it with his trademark humor:

"There was a time when newspapers said that only twelve men understood the theory of relativity. I don't think it was ever like that [...] On the other hand, I think I can safely say that no one understands quantum mechanics."

And that was said by one of the most brilliant physicists of the twentieth century, Nobel Prize winner and one of the fathers of quantum electrodynamics. So great is the rarity of quantum behavior in the eyes of a human that, even Albert Einstein himself, in his now mythical phrase, said to Max Born, in a letter written to the German physicist in 1926, "God does not play dice with the universe" in reference to his disbelief about the probabilistic and non-deterministic properties attributed to quantum behavior. To which Niels Bohr - another titan of physics of the twentieth century - replied: "Einstein, stop telling God what to do."

Classical computing

If we want to understand why quantum mechanics proposes a revolution in computer science, we have to understand its fundamental differences from mechanics - and, therefore, - classical computing. Almost all of us have heard of bits of information at some point in our lives. Humans have developed a way of performing complex mathematical calculations by reducing all information to bits - the fundamental units of information with which a machine knows how to work -, which are the famous zeros and ones (0 and 1). With two simple values, we have been able to model our entire mathematical world. And why? Some will ask. Why base 2 and not 5 or 7? Well, in our classic physical world (in which we live day to day) differentiating between 0 and 1 is relatively simple; on and off, as in the case of an electrical switch, or north or south magnetization, in the case of a magnetic hard drive. For a binary world, we have developed an entire coding language based on two states: 0 and 1.

Quantum computing

In quantum computing, instead of bits, we use qubits. Qubits use several "strange" properties of quantum mechanics that allow them to represent infinite states at once between zero and one of the classic bits. To understand it, it's as if a bit could only represent an on or off state in a light bulb, while a qubit can represent all the light bulb's illumination intensities. This property is known as "quantum superposition" and allows a quantum computer to explore millions of possible solutions at the same time. But this is not all in quantum computing. If quantum superposition seems strange to you, wait until you see quantum entanglement. Thanks to this property, two "entangled" particles (or two qubits) are connected "at a distance" so that the state of one determines the state of the other. So, with these two properties we have information qubits, which can represent infinite states and are connected to each other. This system potentially has an exponentially greater computing capacity than our computers based on classical computing.

Two application cases of quantum computing

1. Drug discovery and personalized medicine. Quantum computers can simulate complex molecular interactions that are impossible to compute with classical computing. For example, protein folding – fundamental to understanding diseases such as Alzheimer's – requires analyzing trillions of possible configurations. A quantum computer could shave years of research to weeks, speeding up the development of new drugs and personalized treatments based on each patient's genetic profile.

2. Logistics optimization and climate change. Companies like Volkswagen already use quantum computing to optimize traffic routes in real time. On a larger scale, these systems could revolutionize the energy management of entire cities, optimizing smart grids that integrate renewables efficiently, or design new materials for CO2 capture that help combat climate change.

A good read recommended for a complete review of quantum computing here.

The role of open data (and computing resources)

The democratization of access to quantum computing will depend crucially on two pillars: open computing resources and quality public datasets. This combination is creating an ecosystem where quantum innovation no longer requires millions of dollars in infrastructure. Here are some options available for each of these pillars.

- Free access to real quantum hardware:

- IBM Quantum Platform: Provides free monthly access to quantum systems of more than 100 qubits for anyone in the world. With more than 400,000 registered users who have generated more than 2,800 scientific publications, it demonstrates how open access accelerates research. Any researcher can sign up for the platform and start experimenting in minutes.

- Open Quantum Institute (OQI): launched at CERN (the European Organization for Nuclear Research) in 2024, it goes further, providing not only access to quantum computing but also mentoring and educational resources for underserved regions. Its hackathon program in 2025 includes events in Lebanon, the United Arab Emirates, and other countries, specifically designed to mitigate the quantum digital divide.

- Public datasets for the development of quantum algorithms:

- QDataSet: Offers 52 public datasets with simulations of one- and two-qubit quantum systems, freely available for training quantum machine learning (ML) algorithms. Researchers without resources to generate their own simulation data can access its repository on GitHub and start developing algorithms immediately.

- ClimSim: This is a public climate-related modeling dataset that is already being used to demonstrate the first quantum ML algorithms applied to climate change. It allows any team, regardless of their budget, to work on real climate problems using quantum computing.

- PennyLane Datasets: is an open collection of molecules, quantum circuits, and physical systems that allows pharmaceutical startups without resources to perform expensive simulations and experiment with quantum-assisted drug discovery.

Real cases of inclusive innovation

The possibilities offered by the use of open data to quantum computing have been evident in various use cases, the result of specific research and calls for grants, such as:

- The Government of Canada launched in 2022 "Quantum Computing for Climate", a specific call for SMEs and startups to develop quantum applications using public climate data, demonstrating how governments can catalyze innovation by providing both data and financing for its use.

- The UK Quantum Catalyst Fund (£15 million) funds projects that combine quantum computing with public data from the UK's National Health Service (NHS) for problems such as optimising energy grids and medical diagnostics, creating solutions of public interest verifiable by the scientific community.

- The Open Quantum Institute's (OQI) 2024 report details 10 use cases for the UN Sustainable Development Goals developed collaboratively by experts from 22 countries, where the results and methodologies are publicly accessible, allowing any institution to replicate or improve these works).

- Red.es has opened an expression of interest aimed at agents in the quantum technologies ecosystem to collect ideas, proposals and needs that contribute to the design of the future lines of action of the National Strategy for Quantum Technologies 2025–2030, financed with 40 million euros from the ERDF Funds.

Current State of Quantum Computing

We are in the NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) era, a term coined by physicist John Preskill in 2018, which describes quantum computers with 50-100 physical qubits. These systems are powerful enough to perform certain calculations beyond the classical capabilities, but they suffer from incoherence, frequent errors that make them unviable in market applications.

IBM, Google, and startups like IonQ offer cloud access to their quantum systems, with IBM providing public access through the IBM Quantum Platform since 2016, being one of the first publicly accessible quantum processors connected to the cloud.

In 2019, Google achieved "quantum supremacy" with its 53-qubit Sycamore processor, which performed a calculation in about 200 seconds that would take about 10,000 years to a state-of-the-art classical supercomputer.

The latest independent analyses suggest that practical quantum applications may emerge around 2035-2040, assuming continued exponential growth in quantum hardware capabilities. IBM has committed to delivering a large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computer, IBM Quantum Starling, by 2029, with the goal of running quantum circuits comprising 100 million quantum gates on 200 logical qubits.

The Global Race for Quantum Leadership

International competition for dominance in quantum technologies has triggered an unprecedented wave of investment. According to McKinsey, until 2022 the officially recognized level of public investment in China (15,300 million dollars) exceeds that of the European Union (7,200 million dollars), the United States 1,900 million dollars) and Japan (1,800 million dollars) combined.

Domestically, the UK has committed £2.5 billion over ten years to its National Quantum Strategy to make the country a global hub for quantum computing, and Germany has made one of the largest strategic investments in quantum computing, allocating €3 billion under its economic stimulus plan.

Investment in the first quarter of 2025 shows explosive growth: quantum computing companies raised more than $1.25 billion, more than double the previous year, an increase of 128%, reflecting a growing confidence that this technology is approaching commercial relevance.

To end the section, a fantastic short interview with Ignacio Cirac, one of the "Spanish fathers" of quantum computing.

Quantum Spain Initiative

In the case of Spain, 60 million euros have been invested in Quantum Spain, coordinated by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center. The project includes:

- Installation of the first quantum computer in southern Europe.

- Network of 25 research nodes distributed throughout the country.

- Training of quantum talent in Spanish universities.

- Collaboration with the business sector for real-world use cases.

This initiative positions Spain as a quantum hub in southern Europe, crucial for not being technologically dependent on other powers.

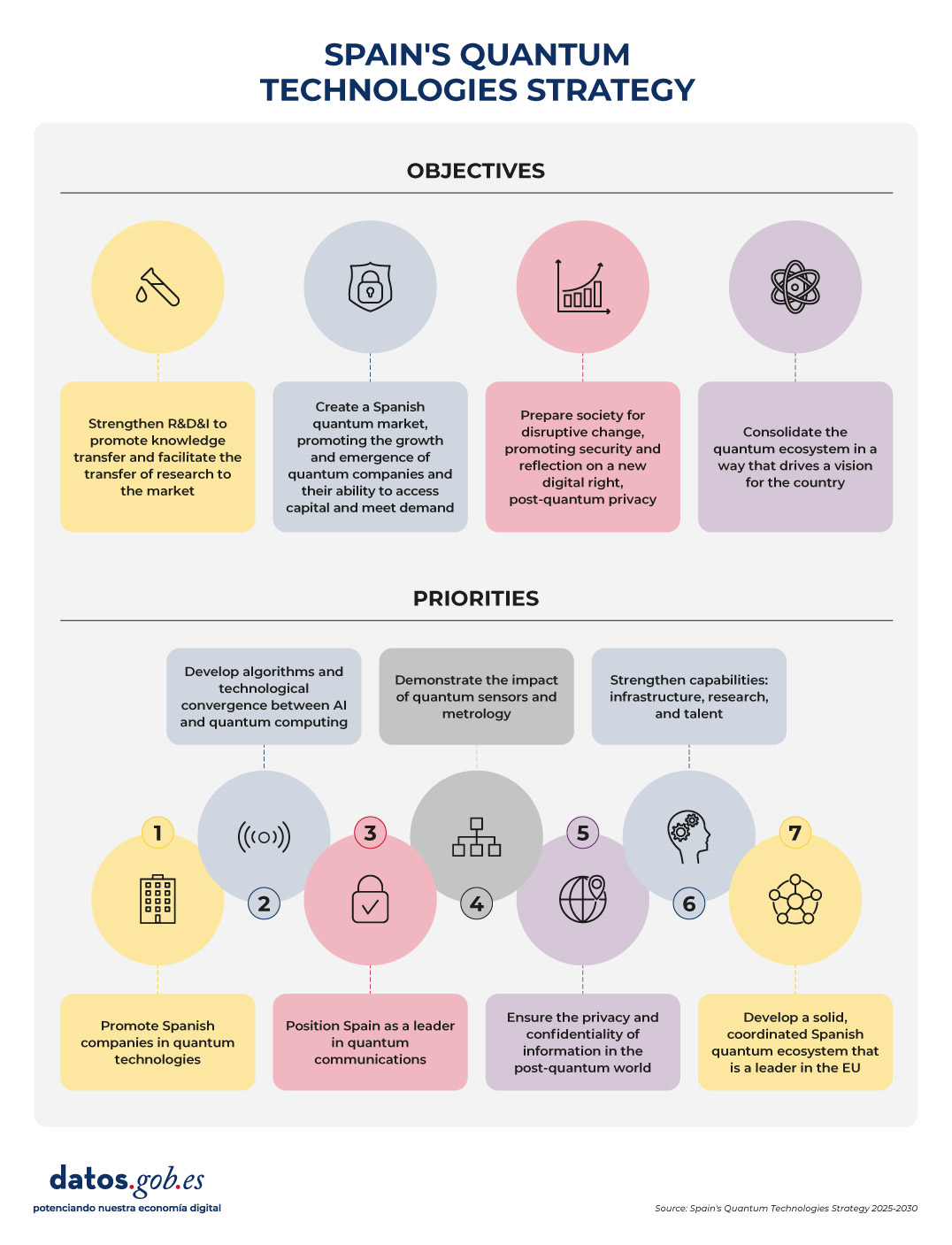

In addition, Spain's Quantum Technologies Strategy has recently been presented with an investment of 800 million euros. This strategy is structured into 4 strategic objectives and 7 priority actions.

Strategic objectives:

- Strengthen R+D+I to promote the transfer of knowledge and facilitate research reaching the market.

- To create a Spanish quantum market, promoting the growth and emergence of quantum companies and their ability to access capital and meet demand.

- Prepare society for disruptive change, promoting security and reflection on a new digital right, post-quantum privacy.

- Consolidate the quantum ecosystem in a way that drives a vision of the country.

Priority actions:

- Priority 1: To promote Spanish companies in quantum technologies.

- Priority 2: Develop algorithms and technological convergence between AI and Quantum.

- Priority 3: Position Spain as a benchmark in quantum communications.

- Priority 4: Demonstrate the impact of quantum sensing and metrology.

- Priority 5: Ensure the privacy and confidentiality of information in the post-quantum world.

- Priority 6: Strengthening capacities: infrastructure, research and talent.

- Priority 7: Develop a solid, coordinated and leading Spanish quantum ecosystem in the EU.

Figure 1. Spain's quantum technology strategy. Source: Author's own elaboration

In short, quantum computing and open data represent a major technological evolution that affects the way we generate and apply knowledge. If we can build a truly inclusive ecosystem—where access to quantum hardware, public datasets, and specialized training is within anyone's reach—we will open the door to a new era of collaborative innovation with a major global impact.

Content created by Alejandro Alija, expert in Digital Transformation and Innovation. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The European open data portal has published the third volume of its Use Case Observatory, a report that compiles the evolution of data reuse projects across Europe. This initiative highlights the progress made in four areas: economic, governmental, social and environmental impact.

The closure of a three-year investigation

Between 2022 and 2025, the European Open Data Portal has systematically monitored the evolution of various European projects. The research began with an initial selection of 30 representative initiatives, which were analyzed in depth to identify their potential for impact.

After two years, 13 projects continued in the study, including three Spanish ones: Planttes, Tangible Data and UniversiDATA-Lab. Its development over time was studied to understand how the reuse of open data can generate real and sustainable benefits.

The publication of volume III in October 2025 marks the closure of this series of reports, following volume I (2022) and volume II (2024). This last document offers a longitudinal view, showing how the projects have matured in three years of observation and what concrete impacts they have generated in their respective contexts.

Common conclusions

This third and final report compiles a number of key findings:

Economic impact

Open data drives growth and efficiency across industries. They contribute to job creation, both directly and indirectly, facilitate smarter recruitment processes and stimulate innovation in areas such as urban planning and digital services.

The report shows the example of:

- Naar Jobs (Belgium): an application for job search close to users' homes and focused on the available transport options.

This application demonstrates how open data can become a driver for regional employment and business development.

Government impact

The opening of data strengthens transparency, accountability and citizen participation.

Two use cases analysed belong to this field:

- Waar is mijn stemlokaal? (Netherlands): platform for the search for polling stations.

- Statsregnskapet.no (Norway): website to visualize government revenues and expenditures.

Both examples show how access to public information empowers citizens, enriches the work of the media, and supports evidence-based policymaking. All of this helps to strengthen democratic processes and trust in institutions.

Social impact

Open data promotes inclusion, collaboration, and well-being.

The following initiatives analysed belong to this field:

- UniversiDATA-Lab (Spain): university data repository that facilitates analytical applications.

- VisImE-360 (Italy): a tool to map visual impairment and guide health resources.

- Tangible Data (Spain): a company focused on making physical sculptures that turn data into accessible experiences.

- EU Twinnings (Netherlands): platform that compares European regions to find "twin cities"

- Open Food Facts (France): collaborative database on food products.

- Integreat (Germany): application that centralizes public information to support the integration of migrants.

All of them show how data-driven solutions can amplify the voice of vulnerable groups, improve health outcomes and open up new educational opportunities. Even the smallest effects, such as improvement in a single person's life, can prove significant and long-lasting.

Environmental impact

Open data acts as a powerful enabler of sustainability.

As with environmental impact, in this area we find a large number of use cases:

- Digital Forest Dryads (Estonia): a project that uses data to monitor forests and promote their conservation.

- Air Quality in Cyprus (Cyprus): platform that reports on air quality and supports environmental policies.

- Planttes (Spain): citizen science app that helps people with pollen allergies by tracking plant phenology.

- Environ-Mate (Ireland): a tool that promotes sustainable habits and ecological awareness.

These initiatives highlight how data reuse contributes to raising awareness, driving behavioural change and enabling targeted interventions to protect ecosystems and strengthen climate resilience.

Volume III also points to common challenges: the need for sustainable financing, the importance of combining institutional data with citizen-generated data, and the desirability of involving end-users throughout the project lifecycle. In addition, it underlines the importance of European collaboration and transnational interoperability to scale impact.

Overall, the report reinforces the relevance of continuing to invest in open data ecosystems as a key tool to address societal challenges and promote inclusive transformation.

The impact of Spanish projects on the reuse of open data

As we have mentioned, three of the use cases analysed in the Use Case Observatory have a Spanish stamp. These initiatives stand out for their ability to combine technological innovation with social and environmental impact, and highlight Spain 's relevance within the European open data ecosystem. His career demonstrates how our country actively contributes to transforming data into solutions that improve people's lives and reinforce sustainability and inclusion. Below, we zoom in on what the report says about them.

This citizen science initiative helps people with pollen allergies through real-time information about allergenic plants in bloom. Since its appearance in Volume I of the Use Case Observatory, it has evolved as a participatory platform in which users contribute photos and phenological data to create a personalized risk map. This participatory model has made it possible to maintain a constant flow of information validated by researchers and to offer increasingly complete maps. With more than 1,000 initial downloads and about 65,000 annual visitors to its website, it is a useful tool for people with allergies, educators and researchers.

The project has strengthened its digital presence, with increasing visibility thanks to the support of institutions such as the Autonomous University of Barcelona and the University of Granada, in addition to the promotion carried out by the company Thigis.

Its challenges include expanding geographical coverage beyond Catalonia and Granada and sustaining data participation and validation. Therefore, looking to the future, it seeks to extend its territorial reach, strengthen collaboration with schools and communities, integrate more data in real time and improve its predictive capabilities.

Throughout this time, Planttes has established herself as an example of how citizen-driven science can improve public health and environmental awareness, demonstrating the value of citizen science in environmental education, allergy management, and climate change monitoring.

The project transforms datasets into physical sculptures that represent global challenges such as climate change or poverty, integrating QR codes and NFC to contextualize the information. Recognized at the EU Open Data Days 2025, Tangible Data has inaugurated its installation Tangible climate at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid.

Tangible Data has evolved in three years from a prototype project based on 3D sculptures to visualize sustainability data to become an educational and cultural platform that connects open data with society. Volume III of the Use Case Observatory reflects its expansion into schools and museums, the creation of an educational program for 15-year-old students, and the development of interactive experiences with artificial intelligence, consolidating its commitment to accessibility and social impact.

Its challenges include funding and scaling up the education programme, while its future goals include scaling up school activities, displaying large-format sculptures in public spaces, and strengthening collaboration with artists and museums. Overall, it remains true to its mission of making data tangible, inclusive, and actionable.

UniversiDATA-Lab is a dynamic repository of analytical applications based on open data from Spanish universities, created in 2020 as a public-private collaboration and currently made up of six institutions. Its unified infrastructure facilitates the publication and reuse of data in standardized formats, reducing barriers and allowing students, researchers, companies and citizens to access useful information for education, research and decision-making.

Over the past three years, the project has grown from a prototype to a consolidated platform, with active applications such as the budget and retirement viewer, and a hiring viewer in beta. In addition, it organizes a periodic datathon that promotes innovation and projects with social impact.

Its challenges include internal resistance at some universities and the complex anonymization of sensitive data, although it has responded with robust protocols and a focus on transparency. Looking to the future, it seeks to expand its catalogue, add new universities and launch applications on emerging issues such as school dropouts, teacher diversity or sustainability, aspiring to become a European benchmark in the reuse of open data in higher education.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the third volume of the Use Case Observatory confirms that open data has established itself as a key tool to boost innovation, transparency and sustainability in Europe. The projects analysed – and in particular the Spanish initiatives Planttes, Tangible Data and UniversiDATA-Lab – demonstrate that the reuse of public information can translate into concrete benefits for citizens, education, research and the environment.

In any data management environment (companies, public administration, consortia, research projects), having data is not enough: if you don't know what data you have, where it is, what it means, who maintains it, with what quality, when it changed or how it relates to other data, then the value is very limited. Metadata —data about data—is essential for:

-

Visibility and access: Allow users to find what data exists and can be accessed.

-

Contextualization: knowing what the data means (definitions, units, semantics).

-

Traceability/lineage: Understanding where data comes from and how it has been transformed.

-

Governance and control: knowing who is responsible, what policies apply, permissions, versions, obsolescence.

-

Quality, integrity, and consistency: Ensuring data reliability through rules, metrics, and monitoring.

-

Interoperability: ensuring that different systems or domains can share data, using a common vocabulary, shared definitions, and explicit relationships.

In short, metadata is the lever that turns "siloed" data into a governed information ecosystem. As data grows in volume, diversity, and velocity, its function goes beyond simple description: metadata adds context, allows data to be interpreted, and makes it findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable (FAIR).

In the new context driven by artificial intelligence, this metadata layer becomes even more relevant, as it provides the provenance information needed to ensure traceability, reliability, and reproducibility of results. For this reason, some recent frameworks extend these principles to FAIR-R, where the additional "R" highlights the importance of data being AI-ready, i.e. that it meets a series of technical, structural and quality requirements that optimize its use by artificial intelligence algorithms.

Thus, we are talking about enriched metadata, capable of connecting technical, semantic and contextual information to enhance machine learning, interoperability between domains and the generation of verifiable knowledge.

From traditional metadata to "rich metadata"

Traditional metadata

In the context of this article, when we talk about metadata with a traditional use, we think of catalogs, dictionaries, glossaries, database data models, and rigid structures (tables and columns). The most common types of metadata are:

-

Technical metadata: column type, length, format, foreign keys, indexes, physical locations.

-

Business/Semantic Metadata: Field Name, Description, Value Domain, Business Rules, Business Glossary Terms.

-

Operational/execution metadata: refresh rate, last load, processing times, usage statistics.

-

Quality metadata: percentage of null values, duplicates, validations.

-

Security/access metadata: access policies, permissions, sensitivity rating.

-

Lineage metadata: Transformation tracing in data pipelines .

This metadata is usually stored in repositories or cataloguing tools, often with tabular structures or relational bases, with predefined links.

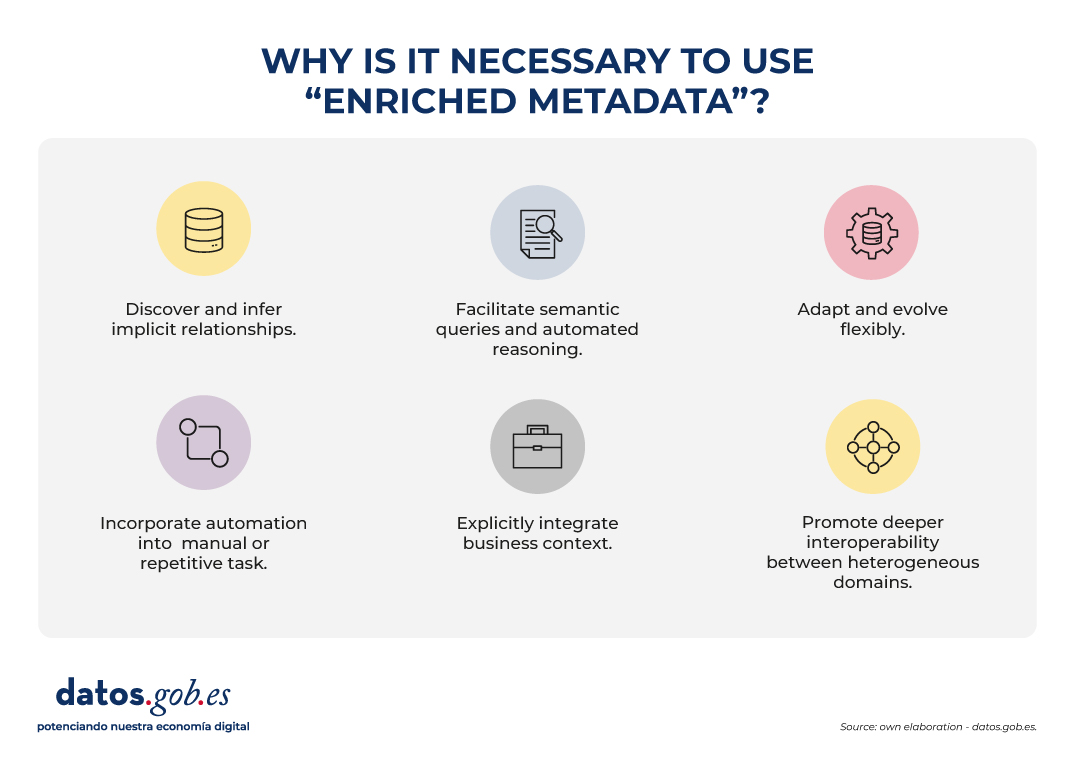

Why "rich metadata"?

Rich metadata is a layer that not only describes attributes, but also:

- They discover and infer implicit relationships, identifying links that are not expressly defined in data schemas. This allows, for example, to recognize that two variables with different names in different systems actually represent the same concept ("altitude" and "elevation"), or that certain attributes maintain a hierarchical relationship ("municipality" belongs to "province").

- They facilitate semantic queries and automated reasoning, allowing users and machines to explore relationships and patterns that are not explicitly defined in databases. Rather than simply looking for exact matches of names or structures, rich metadata allows you to ask questions based on meaning and context. For example, automatically identifying all datasets related to "coastal cities" even if the term does not appear verbatim in the metadata.

- They adapt and evolve flexibly, as they can be extended with new entity types, relationships, or domains without the need to redesign the entire catalog structure. This allows new data sources, models or standards to be easily incorporated, ensuring the long-term sustainability of the system.

- They incorporate automation into tasks that were previously manual or repetitive, such as duplication detection, automatic matching of equivalent concepts, or semantic enrichment using machine learning. They can also identify inconsistencies or anomalies, improving the quality and consistency of metadata.

- They explicitly integrate the business context, linking each data asset to its operational meaning and its role within organizational processes. To do this, they use controlled vocabularies, ontologies or taxonomies that facilitate a common understanding between technical teams, analysts and business managers.

- They promote deeper interoperability between heterogeneous domains, which goes beyond the syntactic exchange facilitated by traditional metadata. Rich metadata adds a semantic layer that allows you to understand and relate data based on its meaning, not just its format. Thus, data from different sources or sectors – for example, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Building Information Modeling (BIM) or the Internet of Things (IoT) – can be linked in a coherent way within a shared conceptual framework. This semantic interoperability is what makes it possible to integrate knowledge and reuse information between different technical and organizational contexts.

This turns metadata into a living asset, enriched and connected to domain knowledge, not just a passive "record".

The Evolution of Metadata: Ontologies and Knowledge Graphs

The incorporation of ontologies and knowledge graphs represents a conceptual evolution in the way metadata is described, related and used, hence we speak of enriched metadata. These tools not only document the data, but connect them within a network of meaning, allowing the relationships between entities, concepts, and contexts to be explicit and computable.

In the current context, marked by the rise of artificial intelligence, this semantic structure takes on a fundamental role: it provides algorithms with the contextual knowledge necessary to interpret, learn and reason about data in a more accurate and transparent way. Ontologies and graphs allow AI systems not only to process information, but also to understand the relationships between elements and to generate grounded inferences, opening the way to more explanatory and reliable models.

This paradigm shift transforms metadata into a dynamic structure, capable of reflecting the complexity of knowledge and facilitating semantic interoperability between different domains and sources of information. To understand this evolution, it is necessary to define and relate some concepts:

Ontologies

In the world of data, an ontology is a highly organized conceptual map that clearly defines:

- What entities exist (e.g., city, river, road).

- What properties they have (e.g. a city has a name, town, zip code).

- How they relate to each other (e.g. a river runs through a city, a road connects two municipalities).

The goal is for people and machines to share the same vocabulary and understand data in the same way. Ontologies allow:

- Define concepts and relationships: for example, "a plot belongs to a municipality", "a building has geographical coordinates".

- Set rules and restrictions: such as "each building must be exactly on a cadastral plot".

- Unify vocabularies: if in one system you say "plot" and in another "cadastral unit", ontology helps to recognize that they are analogous.

- Make inferences: from simple data, discover new knowledge (if a building is on a plot and the plot in Seville, it can be inferred that the building is in Seville).

- Establish a common language: they work as a dictionary shared between different systems or domains (GIS, BIM, IoT, cadastre, urban planning).

In short: an ontology is the dictionary and the rules of the game that allow different geospatial systems (maps, cadastre, sensors, BIM, etc.) to understand each other and work in an integrated way.

Knowledge Graphs

A knowledge graph is a way of organizing information as if it were a network of concepts connected to each other.

-

Nodes represent things or entities, such as a city, a river, or a building.

-

The edges (lines) show the relationships between them, for example: "is in", "crosses" or "belongs to".

-

Unlike a simple drawing of connections, a knowledge graph also explains the meaning of those relationships: it adds semantics.

A knowledge graph combines three main elements:

-

Data: specific cases or instances, such as "Seville", "Guadalquivir River" or "Seville City Hall Building".

-

Semantics (or ontology): the rules and vocabularies that define what kinds of things exist (cities, rivers, buildings) and how they can relate to each other.

-

Reasoning: the ability to discover new connections from existing ones (for example, if a river crosses a city and that city is in Spain, the system can deduce that the river is in Spain).

In addition, knowledge graphs make it possible to connect information from different fields (e.g. data on people, places and companies) under the same common language, facilitating analysis and interoperability between disciplines.

In other words, a knowledge graph is the result of applying an ontology (the data model) to several individual datasets (spatial elements, other territory data, patient records or catalog products, etc.). Knowledge graphs are ideal for integrating heterogeneous data, because they do not require a previously complete rigid schema: they can be grown flexibly. In addition, they allow semantic queries and navigation with complex relationships. Here's an example for spatial data to understand the differences:

|

Spatial data ontology (conceptual model) |

Knowledge graph (specific examples with instances) |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Use Cases

To better understand the value of smart metadata and semantic catalogs, there is nothing better than looking at examples where they are already being applied. These cases show how the combination of ontologies and knowledge graphs makes it possible to connect dispersed information, improve interoperability and generate actionable knowledge in different contexts.

From emergency management to urban planning or environmental protection, different international projects have shown that semantics is not just theory, but a practical tool that transforms data into decisions.

Some relevant examples include:

- LinkedGeoData that converted OpenStreetMap data into Linked Data, linking it to other open sources.

- Virtual Singapore is a 3D digital twin that integrates geospatial, urban and real-time data for simulation and planning.

- JedAI-spatial is a tool for interconnecting 3D spatial data using semantic relationships.

- SOSA Ontology, a standard widely used in sensor and IoT projects for environmental observations with a geospatial component.

- European projects on digital building permits (e.g. ACCORD), which combine semantic catalogs, BIM models, and GIS data to automatically validate building regulations.

Conclusions

The evolution towards rich metadata, supported by ontologies, knowledge graphs and FAIR-R principles, represents a substantial change in the way data is managed, connected and understood. This new approach makes metadata an active component of the digital infrastructure, capable of providing context, traceability and meaning, and not just describing information.

Rich metadata allows you to learn from data, improve semantic interoperability between domains, and facilitate more expressive queries, where relationships and dependencies can be discovered in an automated way. In this way, they favor the integration of dispersed information and support both informed decision-making and the development of more explanatory and reliable artificial intelligence models.

In the field of open data, these advances drive the transition from descriptive repositories to ecosystems of interconnected knowledge, where data can be combined and reused in a flexible and verifiable way. The incorporation of semantic context and provenance reinforces transparency, quality and responsible reuse.

This transformation requires, however, a progressive and well-governed approach: it is essential to plan for systems migration, ensure semantic quality, and promote the participation of multidisciplinary communities.

In short, rich metadata is the basis for moving from isolated data to connected and traceable knowledge, a key element for interoperability, sustainability and trust in the data economy.

Content prepared by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The Provincial Council of Bizkaia has launched the Data Journalism Challenge, a competition aimed at rewarding creativity, rigour and talent in the use of open data. This initiative seeks to promote journalistic projects that use the public data available on the Open Data Bizkaia platform to create informative content with a strong visual component. Whether through interactive graphics, maps, animated videos or in-depth reports, the goal is to transform data into narratives that connect with citizens.

Who can participate?

The call is open to individuals over 18 years of age, both individually and in teams of up to four members. Each participant may submit proposals in one or more of the available categories.

It is an opportunity of special relevance for students, entrepreneurs, developers, design professionals or journalists with an interest in open data.

Three categories to boost the use of open data

The competition is divided into three categories, each with its own approach and evaluation criteria:

-

Dynamic data representation: Projects that present data in an interactive, clear, and visually appealing way.

-

Data storytelling through animated video: audiovisual narratives that explain phenomena or trends using public data.

-

Reporting + Data: journalistic articles that integrate data analysis with research and depth of information.

As we have previously mentioned, all projects must be based on the public data available on the Open Data Bizkaia platform, which offers information on multiple areas: economy, environment, mobility, health, culture, etc. It is a rich and accessible source for building relevant and well-grounded stories.

Up to 4,500 euros in prizes

For each category, the following prizes will be awarded:

-

First place: 1,500 euros

-

Second place: 750 euros

The prizes will be subject to the corresponding tax withholdings. Since the same person can submit proposals to several categories, and these will be evaluated independently, it is possible for a single participant to win more than one prize. Therefore, a single participant will be able to win up to 4,500 euros, if they win in all three categories.

What are the evaluation criteria?

The awards will be made through the competitive concurrence procedure. All the projects received in the period enabled for this will be evaluated by the jury, according to a series of specific criteria for each category:

-

Dynamic data representation:

-

Communicative clarity (30%)

-

Interactivity (25%)

-

Design and usability (20%)

-

Originality in representation (15%)

-

Rigor and fidelity of data (10%)

-

Data storytelling in animation video

-

Narrative and script (30%)

-

Visual creativity and technical innovation (25%)

-

Informational clarity (20%)

-

Emotional and aesthetic impact (15%)

-

Rigorous and honest use of data (10%)

-

Feature + Data

-

Journalistic quality and analytical depth (30%)

-

Narrative integration of data (25%)

-

Originality in approach and format (20%)

-

Design and user experience (15%)

-

Transparency and traceability of sources (10%)

How are applications submitted?

The deadline for submitting projects began on November 3 and will be open until December 3, 2025 at 11:59 p.m. Applications may be submitted in a variety of ways:

-

Electronically, through the electronic office of Bizkaia, using the procedure code 2899.

-

In person, at the General Registry of the Laguntza Office (c/ Diputación, 7, Bilbao), at any other public registry or at the Post Office.

In the case of group projects, a single application signed by a representative must be submitted. This person will assume the dialogue with the organizing General Directorate, taking care of the procedures and the fulfillment of the corresponding obligations.

The documentation that must be submitted is:

-

The project to be evaluated.

-

The certificate of being up to date with tax obligations.

-

The certificate of being up to date with Social Security obligations.

-

The direct debit form, only in the event that the applicant objects to this Administration checking the bank details by its own means.

Contact Information

For queries or additional information, please contact the Provincial Council of Bizkaia. Specifically, with the Department of Public Administration and Institutional Relations, Technical Advisory Section c/ Gran Vía, 2 (48009) in the city of Bilbao. Doubts will also be answered by calling 944 068 000 and by email SAT@bizkaia.eus.

This competition represents an opportunity to explore the potential of data journalism and contribute to more transparent and accessible communication. The projects presented will be able to highlight the potential of open data to facilitate the understanding of issues of public interest, in a clear and simple way.

For more details, it is recommended to read the information

On October 6, the V Open Government Plan was approved, an initiative that gives continuity to the commitment of public administrations to transparency, citizen participation and accountability. This new plan, which will be in force until 2029, includes 218 measures grouped into 10 commitments that affect the various levels of the Administration.

In this article we are going to review the key points of the Plan, focusing on those commitments related to data and access to public information.

A document resulting from collaboration

The process of preparing the V Open Government Plan has been developed in a participatory and collaborative way, with the aim of collecting proposals from different social actors. To this end, a public consultation was opened in which citizens, civil society organizations and institutional representatives were able to contribute ideas and suggestions. A series of deliberative workshops were also held. In total, 620 contributions were received from civil society and more than 300 proposals from ministries, autonomous communities and cities, and representatives of local entities.

These contributions were analysed and integrated into the plan's commitments, which were subsequently validated by the Open Government Forum. The result is a document that reflects a shared vision on how to advance transparency, participation and accountability in the public administrations as a whole.

10 main lines of action with a prominent role for open data

As a result of this collaborative work, 10 lines of action have been established. The first nine commitments include initiatives from the General State Administration (AGE), while the tenth groups together the contributions of autonomous communities and local entities:

- Participation and civic space.

- Transparency and access to information.

- Integrity and accountability.

- Open administration.

- Digital governance and artificial intelligence.

- Fiscal openness: clear and open accounts.

- Truthful information / information ecosystem.

- Dissemination, training and promotion of open government.

- Open Government Observatory.

- Open state.

Figure 1. 10 lines of action of the V Open Government Plan. Source: Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration.

Data and public information are a key element in all of them. However, most of the measures related to this field are found within line of action 2, where there is a specific section on opening and reusing public information data. Among the measures envisaged, the following are contemplated:

- Data governance model: it is proposed to create a regulatory framework that facilitates the responsible and efficient use of public data in the AGE. It includes the regulation of collegiate bodies for the exchange of data, the application of European regulations and the creation of institutional spaces to design public policies based on data.

- Data strategy for a citizen-centred administration: it seeks to establish a strategic framework for the ethical and transparent use of data in the Administration.

- Publication of microdata from electoral surveys: the Electoral Law will be amended to include the obligation to publish anonymized microdata from electoral surveys. This improves the reliability of studies and facilitates open access to individual data for analysis.

- Support for local entities in the opening of data: a grant program has been launched to promote the opening of homogeneous and quality data in local entities through calls and/or collaboration agreements. In addition, its reuse will be promoted through awareness-raising actions, development of demonstrator solutions and inter-administrative collaboration to promote public innovation.

- Openness of data in the Administration of Justice: official data on justice will continue to be published on public portals, with the aim of making the Administration of Justice more transparent and accessible.

- Access and integration of high-value geospatial information: the aim is to facilitate the reuse of high-value spatial data in categories such as geospatial, environment and mobility. The measure includes the development of digital maps, topographic bases and an API to improve access to this information by citizens, administrations and companies.

- Open data of the BORME: work will be done to promote the publication of the content of the Official Gazette of the Mercantile Registry, especially the section on entrepreneurs, as open data in machine-readable formats and accessible through APIs.

- Databases of the Central Archive of the Treasury: the public availability of the records of the Central Archive of the Ministry of Finance that do not contain personal data or are not subject to legal restrictions is promoted.

- Secure access to confidential public data for research and innovation: the aim is to establish a governance framework and controlled environments that allow researchers to securely and ethically access public data subject to confidentiality.

- Promotion of the secondary use of health data: work will continue on the National Health Data Space (ENDS), aligned with European regulations, to facilitate the use of health data for research, innovation and public policy purposes. The measure includes the promotion of technical infrastructures, regulatory frameworks and ethical guarantees to protect the privacy of citizens.

- Promotion of data ecosystems for social progress: it seeks to promote collaborative data spaces between public and private entities, under clear governance rules. These ecosystems will help develop innovative solutions that respond to social needs, fostering trust, transparency and the fair return of benefits to citizens.

- Enhancement of quality public data for citizens and companies: the generation of quality data will continue to be promoted in the different ministries and agencies, so that they can be integrated into the AGE's centralised catalogue of reusable information.

- Evolution of the datos.gob.es platform: work continues on the optimization of datos.gob.es. This measure is part of a continuous enrichment to address changing citizen needs and emerging trends.

In addition to this specific heading, measures related to open data are also included in other sections. For example, measure 3.5.5 proposes to transform the Public Sector Procurement Platform into an advanced tool that uses Big Data and Artificial Intelligence to strengthen transparency and prevent corruption. Open data plays a central role here, as it allows massive audits and statistical analyses to be carried out to detect irregular patterns in procurement processes. In addition, by facilitating citizen access to this information, social oversight and democratic control over the use of public funds are promoted.

Another example can be found in measure 4.1.1, where it is proposed to develop a digital tool for the General State Administration that incorporates the principles of transparency and open data from its design. The system would allow the traceability, conservation, access and reuse of public documents, integrating archival criteria, clear language and document standardization. In addition, it would be linked to the National Open Data Catalog to ensure that information is available in open and reusable formats.

The document not only highlights the possibilities of open data: it also highlights the opportunities offered by Artificial Intelligence both in improving access to public information and in the generation of open data useful for collective decision-making.

Promotion of open data in the Autonomous Communities and Cities

As mentioned above, the IV Open Government Plan also includes commitments made by regional bodies, which are detailed in line of action 10 on Open State, many of them focused on the availability of public data.

For example, the Government of Catalonia reports its interest in optimising the resources available for the management of requests for access to public information, as well as in publishing disaggregated data on public budgets in areas related to children or climate change. For its part, the Junta de Andalucía wants to promote access to information on scientific personnel and scientific production, and develop a Data Observatory of Andalusian public universities, among other measures. Another example can be found in the Autonomous City of Melilla, which is working on an Open Data Portal.

With regard to the local administration, the commitments have been set through the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces (FEMP). The Network of Local Entities for Transparency and Citizen Participation of the FEMP proposes that local public administrations publish, at least, to choose from the following fields: street; budgets and budget execution; subsidies; public contracting and bidding; municipal register; vehicle census; waste and recycling containers; register of associations; cultural agenda; tourist accommodation; business areas and Industrial; Census of companies or economic agents.

All these measures highlight the interest in open data in Spanish institutions as a key tool to promote open government, promote services and products aligned with citizen needs and optimize decision-making.

A tracking system

The follow-up of the V Open Government Plan is based on a strengthened system of accountability and the strategic use of the HazLab digital platform, where five working groups are hosted, one of them focused on transparency and access to information.

Each initiative of the Plan also has a monitoring file with information on its execution, schedule and results, periodically updated by the responsible units and published on the Transparency Portal.

Conclusions

Overall, the V Open Government Plan seeks a more transparent, participatory Administration oriented to the responsible use of public data. Many of the measures included aim to strengthen the openness of information, improve document management and promote the reuse of data in key sectors such as health, justice or public procurement. This approach not only facilitates citizen access to information, but also promotes innovation, accountability, and a more open and collaborative culture of governance.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is becoming one of the main drivers of increased productivity and innovation in both the public and private sectors, becoming increasingly relevant in tasks ranging from the creation of content in any format (text, audio, video) to the optimization of complex processes through Artificial Intelligence agents.

However, advanced AI models, and in particular large language models, require massive amounts of data for training, optimization, and evaluation. This dependence generates a paradox: at the same time as AI demands more and higher quality data, the growing concern for privacy and confidentiality (General Data Protection Regulation or GDPR), new data access and use rules (Data Act), and quality and governance requirements for high-risk systems (AI Regulation), as well as the inherent scarcity of data in sensitive domains limit access to actual data.

In this context, synthetic data can be an enabling mechanism to achieve new advances, reconciling innovation and privacy protection. On the one hand, they allow AI to be nurtured without exposing sensitive information, and when combined with quality open data, they expand access to domains where real data is scarce or heavily regulated.

What is synthetic data and how is it generated?

Simply put, synthetic data can be defined as artificially fabricated information that mimics the characteristics and distributions of real data. The main function of this technology is to reproduce the statistical characteristics, structure and patterns of the underlying real data. In the domain of official statistics, there are cases such as the United States Census , which publishes partially or totally synthetic products such as OnTheMap (mobility of workers between place of residence and workplace) or SIPP Synthetic Beta (socioeconomic microdata linked to taxes and social security).

The generation of synthetic data is currently a field still in development that is supported by various methodologies. Approaches can range from rule-based methods or statistical modeling (simulations, Bayesian, causal networks), which mimic predefined distributions and relationships, to advanced deep learning techniques. Among the most outstanding architectures we find:

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): a generative model, trained on real data, learns to mimic its characteristics, while a discriminator tries to distinguish between real and synthetic data. Through this iterative process, the generator improves its ability to produce artificial data that is statistically indistinguishable from the originals. Once trained, the algorithm can create new artificial records that are statistically similar to the original sample, but completely new and secure.

- Variational Selfencoders (VAE): These models are based on neural networks that learn a probabilistic distribution in a latent space of the input data. Once trained, the model uses this distribution to obtain new synthetic observations by sampling and decoding the latent vectors. VAEs are often considered a more stable and easier option to train compared to GANs for tabular data generation.

- Autoregressive/hierarchical models and domain simulators: used, for example, in electronic medical record data, which capture temporal and hierarchical dependencies. Hierarchical models structure the problem by levels, first sampling higher-level variables and then lower-level variables conditioned to the previous ones. Domain simulators code process rules and calibrate them with real data, providing control and interpretability and ensuring compliance with business rules.

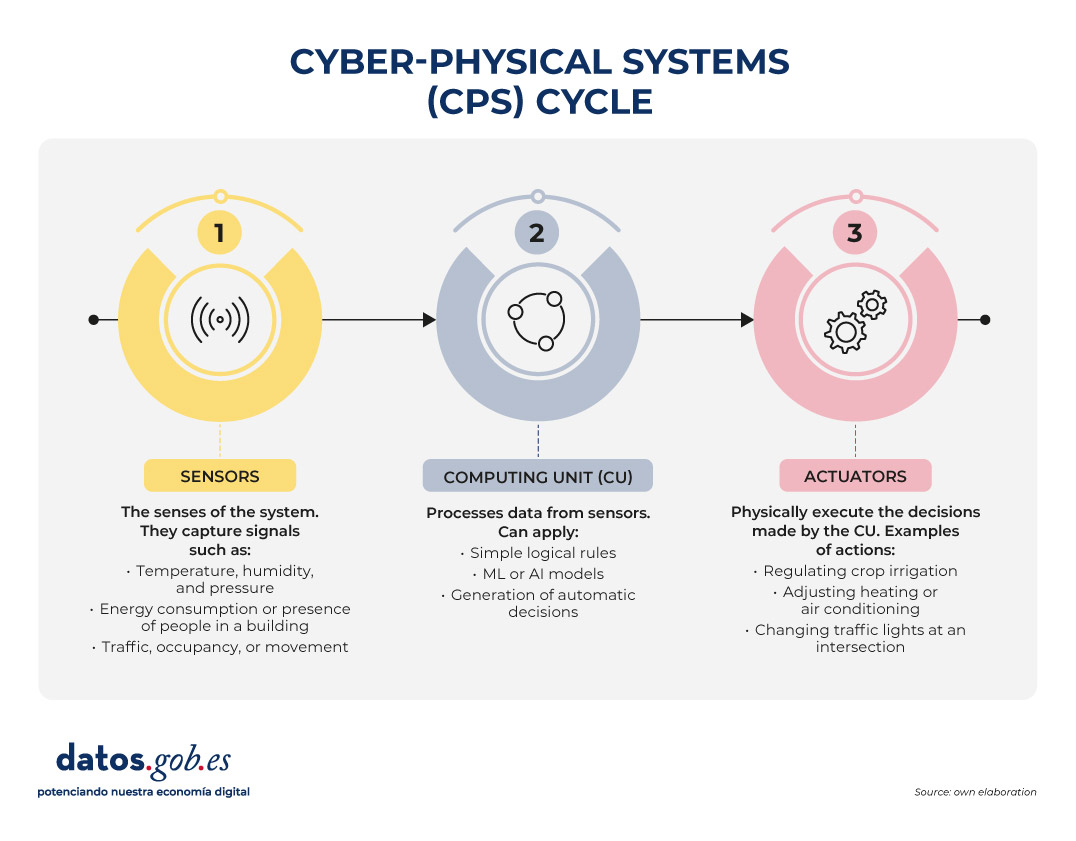

You can learn more about synthetic data and how it's created in this infographic:

Figure 1. Infographic on synthetic data. Source: Authors' elaboration - datos.gob.es.

While synthetic generation inherently reduces the risk of personal data disclosure, it does not eliminate it entirely. Synthetic does not automatically mean anonymous because, if the generators are trained inappropriately, traces of the real set can leak out and be vulnerable to membership inference attacks. Hence, it is necessary to use Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PET) such as differential privacy and to carry out specific risk assessments. The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) has also underlined the need to carry out a privacy assurance assessment before synthetic data can be shared, ensuring that the result does not allow re-identifiable personal data to be obtained.

Differential Privacy (PD) is one of the main technologies in this domain. Its mechanism is to add controlled noise to the training process or to the data itself, mathematically ensuring that the presence or absence of any individual in the original dataset does not significantly alter the final result of the generation. The use of secure methods, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent with Differential Privacy (DP-SGD), ensures that the samples generated do not compromise the privacy of users who contributed their data to the sensitive set.

What is the role of open data?

Obviously, synthetic data does not appear out of nowhere, it needs real high-quality data as a seed and, in addition, it requires good validation practices. For this reason, open data or data that cannot be opened for privacy-related reasons is, on the one hand, an excellent raw material for learning real-world patterns and, on the other, an independent reference to verify that the synthetic resembles reality without exposing people or companies.

As a seed of learning, quality open data, such as high-value datasets, with complete metadata, clear definitions and standardized schemas, provide coverage, granularity and timeliness. Where certain sets cannot be made public for privacy reasons, they can be used internally with appropriate safeguards to produce synthetic data that could be released. In health, for example, there are open generators such as Synthea, which produce fictitious medical records without the restrictions on the use of real data.

On the other hand, compared to a synthetic set, open data allows it to act as a verification standard, to contrast distributions, correlations and business rules, as well as to evaluate the usefulness in real tasks (prediction, classification) without resorting to sensitive information. In this sense, there are already works, such as that of the Welsh Government with health data, which have experimented with different indicators. These include total distance of change (TVD), propensity score and performance in machine learning tasks.

How is synthetic data evaluated?

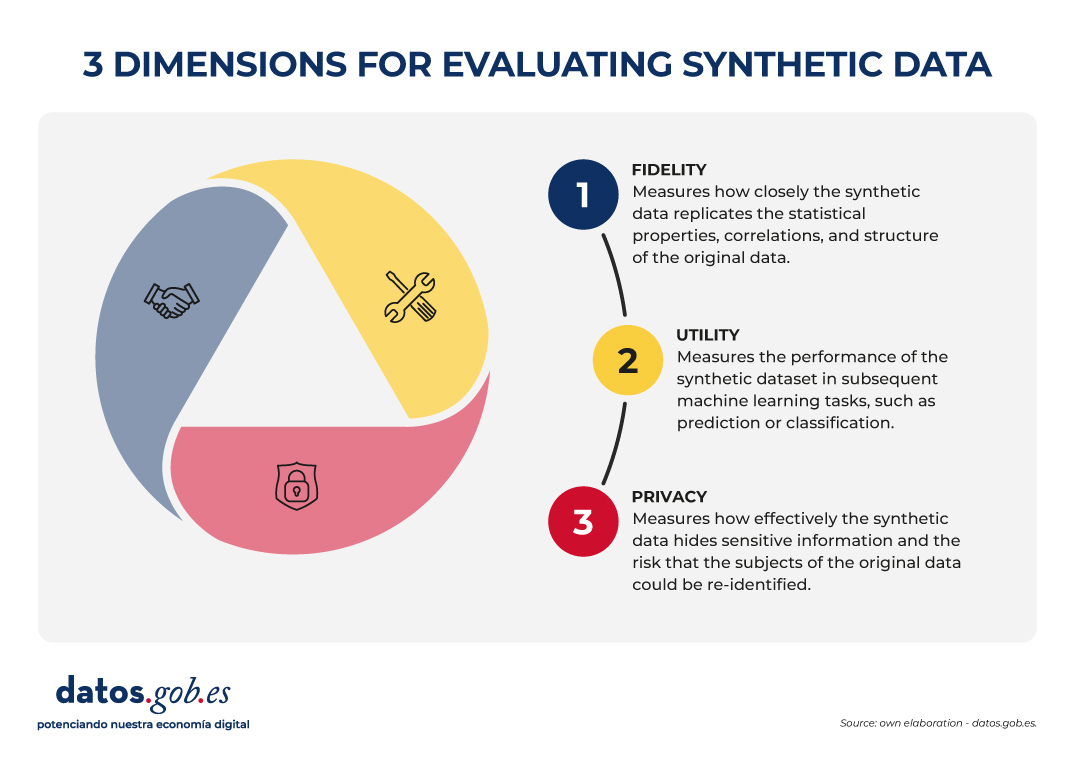

The evaluation of synthetic datasets is articulated through three dimensions that, by their nature, imply a commitment:

- Fidelity: Measures how close the synthetic data is to replicating the statistical properties, correlations, and structure of the original data.

- Utility: Measures the performance of the synthetic dataset in subsequent machine learning tasks, such as prediction or classification.

- Privacy: measures how effectively synthetic data hides sensitive information and the risk that the subjects of the original data can be re-identified.

Figure 2. Three dimensions to evaluate synthetic data. Source: Authors' elaboration - datos.gob.es.

The governance challenge is that it is not possible to optimize all three dimensions simultaneously. For example, increasing the level of privacy (by injecting more noise through differential privacy) can inevitably reduce statistical fidelity and, consequently, usefulness for certain tasks. The choice of which dimension to prioritize (maximum utility for statistical research or maximum privacy) becomes a strategic decision that must be transparent and specific to each use case.

Synthetic open data?

The combination of open data and synthetic data can already be considered more than just an idea, as there are real cases that demonstrate its usefulness in accelerating innovation and, at the same time, protecting privacy. In addition to the aforementioned OnTheMap or SIPP Synthetic Beta in the United States, we also find examples in Europe and the rest of the world. For example, the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC) has analysed the role of AI Generated Synthetic Data in Policy Applications, highlighting its ability to shorten the life cycle of public policies by reducing the burden of accessing sensitive data and enabling more agile exploration and testing phases. He has also documented applications of multipurpose synthetic populations for mobility, energy, or health analysis, reinforcing the idea that synthetic data act as a cross-sectional enabler.

In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) conducted a Synthetic Data Pilot to understand the demand for synthetic data. The pilot explored the production of high-quality synthetic microdata generation tools for specific user requirements.

Also in health , advances are observed that illustrate the value of synthetic open data for responsible innovation. The Department of Health of the Western Australian region has promoted a Synthetic Data Innovation Project and sectoral hackathons where realistic synthetic sets are released that allow internal and external teams to test algorithms and services without access to identifiable clinical information, fostering collaboration and accelerating the transition from prototypes to real use cases.

In short, synthetic data offers a promising, although not sufficiently explored, avenue for the development of artificial intelligence applications, as it contributes to the balance between fostering innovation and protecting privacy.

Synthetic data is not a substitute for open data, but rather enhances each other. In particular, they represent an opportunity for public administrations to expand their open data offering with synthetic versions of sensitive sets for education or research, and to make it easier for companies and independent developers to experiment with regulation and generate greater economic and social value.

Content created by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalisation. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Spain has taken another step towards consolidating a public policy based on transparency and digital innovation. Through the General State Administration, the Government of Spain has signed its adhesion to the International Open Data Charter, within the framework of the IX Global Summit of the Open Government Partnership that is being held these days in Vitoria-Gasteiz.

With this adhesion, data is recognized as a strategic asset for the design of public policies and the improvement of services. In addition, the importance of its openness and reuse, together with the ethical use of artificial intelligence, as key drivers for digital transformation and the generation of social and economic value is underlined.

What is the International Open Data Charter?

The International Open Data Charter (ODC) is a global initiative that promotes the openness and reuse of public data as tools to improve transparency, citizen participation, innovation, and accountability. This initiative was launched in 2015 and is backed by governments, organizations and experts. Its objective is to guide public entities in the adoption of responsible, sustainable open data policies focused on social impact, respecting the fundamental rights of people and communities. To this end, it promotes six principles:

-

Open data by default: data must be published proactively, unless there are legitimate reasons to restrict it (such as privacy or security).

-

Timely and comprehensive data: data should be published in a complete, understandable and agile manner, as often as necessary to be useful. Its original format should also be respected whenever possible.

-