Artificial Intelligence (AI) is becoming one of the main drivers of increased productivity and innovation in both the public and private sectors, becoming increasingly relevant in tasks ranging from the creation of content in any format (text, audio, video) to the optimization of complex processes through Artificial Intelligence agents.

However, advanced AI models, and in particular large language models, require massive amounts of data for training, optimization, and evaluation. This dependence generates a paradox: at the same time as AI demands more and higher quality data, the growing concern for privacy and confidentiality (General Data Protection Regulation or GDPR), new data access and use rules (Data Act), and quality and governance requirements for high-risk systems (AI Regulation), as well as the inherent scarcity of data in sensitive domains limit access to actual data.

In this context, synthetic data can be an enabling mechanism to achieve new advances, reconciling innovation and privacy protection. On the one hand, they allow AI to be nurtured without exposing sensitive information, and when combined with quality open data, they expand access to domains where real data is scarce or heavily regulated.

What is synthetic data and how is it generated?

Simply put, synthetic data can be defined as artificially fabricated information that mimics the characteristics and distributions of real data. The main function of this technology is to reproduce the statistical characteristics, structure and patterns of the underlying real data. In the domain of official statistics, there are cases such as the United States Census , which publishes partially or totally synthetic products such as OnTheMap (mobility of workers between place of residence and workplace) or SIPP Synthetic Beta (socioeconomic microdata linked to taxes and social security).

The generation of synthetic data is currently a field still in development that is supported by various methodologies. Approaches can range from rule-based methods or statistical modeling (simulations, Bayesian, causal networks), which mimic predefined distributions and relationships, to advanced deep learning techniques. Among the most outstanding architectures we find:

- Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): a generative model, trained on real data, learns to mimic its characteristics, while a discriminator tries to distinguish between real and synthetic data. Through this iterative process, the generator improves its ability to produce artificial data that is statistically indistinguishable from the originals. Once trained, the algorithm can create new artificial records that are statistically similar to the original sample, but completely new and secure.

- Variational Selfencoders (VAE): These models are based on neural networks that learn a probabilistic distribution in a latent space of the input data. Once trained, the model uses this distribution to obtain new synthetic observations by sampling and decoding the latent vectors. VAEs are often considered a more stable and easier option to train compared to GANs for tabular data generation.

- Autoregressive/hierarchical models and domain simulators: used, for example, in electronic medical record data, which capture temporal and hierarchical dependencies. Hierarchical models structure the problem by levels, first sampling higher-level variables and then lower-level variables conditioned to the previous ones. Domain simulators code process rules and calibrate them with real data, providing control and interpretability and ensuring compliance with business rules.

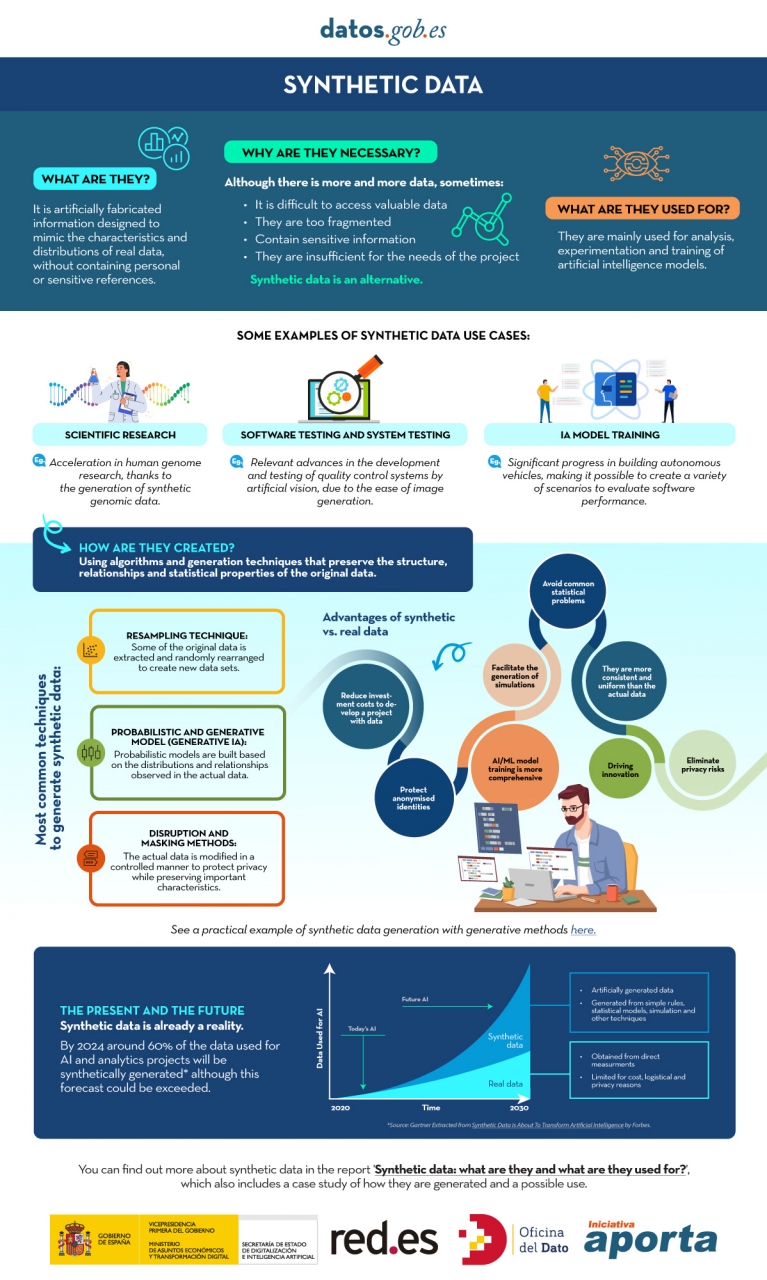

You can learn more about synthetic data and how it's created in this infographic:

Figure 1. Infographic on synthetic data. Source: Authors' elaboration - datos.gob.es.

While synthetic generation inherently reduces the risk of personal data disclosure, it does not eliminate it entirely. Synthetic does not automatically mean anonymous because, if the generators are trained inappropriately, traces of the real set can leak out and be vulnerable to membership inference attacks. Hence, it is necessary to use Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PET) such as differential privacy and to carry out specific risk assessments. The European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) has also underlined the need to carry out a privacy assurance assessment before synthetic data can be shared, ensuring that the result does not allow re-identifiable personal data to be obtained.

Differential Privacy (PD) is one of the main technologies in this domain. Its mechanism is to add controlled noise to the training process or to the data itself, mathematically ensuring that the presence or absence of any individual in the original dataset does not significantly alter the final result of the generation. The use of secure methods, such as Stochastic Gradient Descent with Differential Privacy (DP-SGD), ensures that the samples generated do not compromise the privacy of users who contributed their data to the sensitive set.

What is the role of open data?

Obviously, synthetic data does not appear out of nowhere, it needs real high-quality data as a seed and, in addition, it requires good validation practices. For this reason, open data or data that cannot be opened for privacy-related reasons is, on the one hand, an excellent raw material for learning real-world patterns and, on the other, an independent reference to verify that the synthetic resembles reality without exposing people or companies.

As a seed of learning, quality open data, such as high-value datasets, with complete metadata, clear definitions and standardized schemas, provide coverage, granularity and timeliness. Where certain sets cannot be made public for privacy reasons, they can be used internally with appropriate safeguards to produce synthetic data that could be released. In health, for example, there are open generators such as Synthea, which produce fictitious medical records without the restrictions on the use of real data.

On the other hand, compared to a synthetic set, open data allows it to act as a verification standard, to contrast distributions, correlations and business rules, as well as to evaluate the usefulness in real tasks (prediction, classification) without resorting to sensitive information. In this sense, there are already works, such as that of the Welsh Government with health data, which have experimented with different indicators. These include total distance of change (TVD), propensity score and performance in machine learning tasks.

How is synthetic data evaluated?

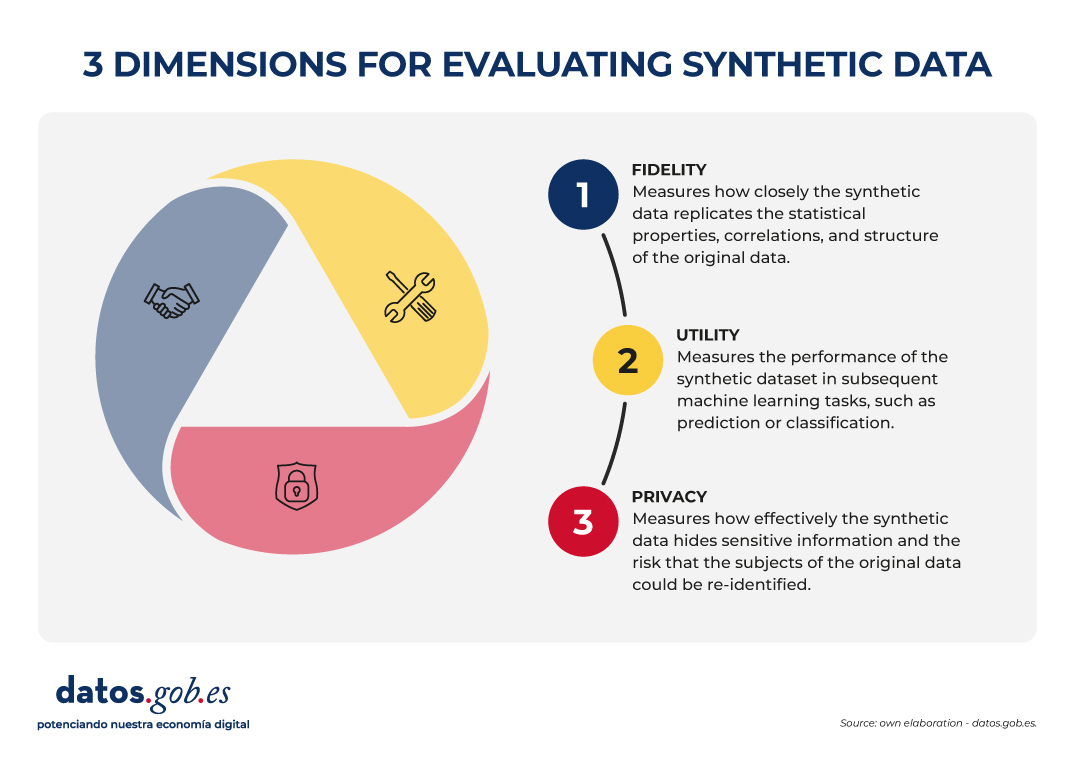

The evaluation of synthetic datasets is articulated through three dimensions that, by their nature, imply a commitment:

- Fidelity: Measures how close the synthetic data is to replicating the statistical properties, correlations, and structure of the original data.

- Utility: Measures the performance of the synthetic dataset in subsequent machine learning tasks, such as prediction or classification.

- Privacy: measures how effectively synthetic data hides sensitive information and the risk that the subjects of the original data can be re-identified.

Figure 2. Three dimensions to evaluate synthetic data. Source: Authors' elaboration - datos.gob.es.

The governance challenge is that it is not possible to optimize all three dimensions simultaneously. For example, increasing the level of privacy (by injecting more noise through differential privacy) can inevitably reduce statistical fidelity and, consequently, usefulness for certain tasks. The choice of which dimension to prioritize (maximum utility for statistical research or maximum privacy) becomes a strategic decision that must be transparent and specific to each use case.

Synthetic open data?

The combination of open data and synthetic data can already be considered more than just an idea, as there are real cases that demonstrate its usefulness in accelerating innovation and, at the same time, protecting privacy. In addition to the aforementioned OnTheMap or SIPP Synthetic Beta in the United States, we also find examples in Europe and the rest of the world. For example, the European Commission's Joint Research Centre (JRC) has analysed the role of AI Generated Synthetic Data in Policy Applications, highlighting its ability to shorten the life cycle of public policies by reducing the burden of accessing sensitive data and enabling more agile exploration and testing phases. He has also documented applications of multipurpose synthetic populations for mobility, energy, or health analysis, reinforcing the idea that synthetic data act as a cross-sectional enabler.

In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) conducted a Synthetic Data Pilot to understand the demand for synthetic data. The pilot explored the production of high-quality synthetic microdata generation tools for specific user requirements.

Also in health , advances are observed that illustrate the value of synthetic open data for responsible innovation. The Department of Health of the Western Australian region has promoted a Synthetic Data Innovation Project and sectoral hackathons where realistic synthetic sets are released that allow internal and external teams to test algorithms and services without access to identifiable clinical information, fostering collaboration and accelerating the transition from prototypes to real use cases.

In short, synthetic data offers a promising, although not sufficiently explored, avenue for the development of artificial intelligence applications, as it contributes to the balance between fostering innovation and protecting privacy.

Synthetic data is not a substitute for open data, but rather enhances each other. In particular, they represent an opportunity for public administrations to expand their open data offering with synthetic versions of sensitive sets for education or research, and to make it easier for companies and independent developers to experiment with regulation and generate greater economic and social value.

Content created by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalisation. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.