In the last fifteen years we have seen how public administrations have gone from publishing their first open datasets to working with much more complex concepts. Interoperability, standards, data spaces or digital sovereignty are some of the trendy concepts. And, in parallel, the web has also changed. That open, decentralized, and interoperable space that inspired the first open data initiatives has evolved into a much more complex ecosystem, where technologies, new standards, and at the same time important challenges such as information silos to digital ethics and technological concentration coexist.

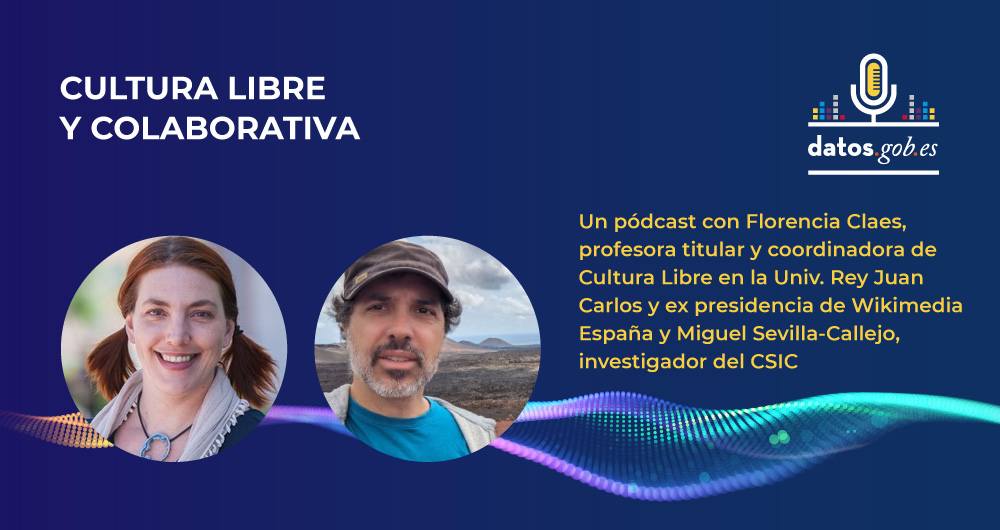

To talk about all this, today we are fortunate to have two voices that have not only observed this evolution, but have been direct protagonists of it at an international level:

- Josema Alonso, with more than twenty-five years of experience working on the open web, data and digital rights, has worked at the World Wide Web Foundation, the Open Government Partnership and the World Economic Forum, among others.

- Carlos Iglesias, an expert in web standards, open data and open government, has advised administrations around the world on more than twenty projects. He has been actively involved in communities such as W3C, the Web Foundation and the Open Knowledge Foundation.

Interview Summary / Transcript

1. At what point do you think we are now and what has changed with respect to that first stage of open data?

Carlos Iglesias: Well, I think what has changed is that we understand that today that initial battle cry of "we want the data now" is not enough. It was a first phase that at the time was very useful and necessary because we had to break with that trend of having data locked up, not sharing data. Let's say that the urgency at that time was simply to change the paradigm and that is why the battle cry was what it was. I have been involved, like Josema, in studying and analyzing all those open data portals and initiatives that arose from this movement. And I have seen that many of them began to grow without any kind of strategy. In fact, several fell by the wayside or did not have a clear vision of what they wanted to do. Simple practice I believe came to the conclusion that the publication of data alone was not enough. And from there I think that they have been proposing, a little with the maturity of the movement, that more things have to be done, and today we talk more about data governance, about opening data with a specific purpose, about the importance of metadata, models. In other words, it is no longer simply having data for the sake of having it, but there is one more vision of data as one of the most valuable elements today, probably, and also as a necessary infrastructure for many things to work today. Just as infrastructures such as road or public transport networks or energy were key in their day. Right now we are at the moment of the great explosion of artificial intelligence. A series of issues converge that have made this explode and the change is immense, despite the fact that we are only talking about perhaps a little more than ten or fifteen years since that first movement of "we want the data now". I think that right now the panorama is completely different.

Josema Alonso: Yes, it is true that we had that idea of "you publish that someone will come and do something with it". And what that did is that people began to become aware. But I, personally, could not have imagined that a few years later we would have even had a directive at European level on the publication of open data. It was something, to be honest, that we received with great pleasure. And then it will begin to be implemented in all member states. That moved consciences a little and moved practices, especially within the administration. There was a lot of fear of "let's see if I put something in there that is problematic, that is of poor quality, that I will be criticized for it", etc. But it began to generate a culture of data and the usefulness of very important data. And as Carlos also commented in recent years, I think that no one doubts this anymore. The investments that are being made, for example, at European level and in Member States, including in our country, in Spain, in the promotion and development of data spaces, are hundreds of millions of euros. Nobody has that kind of doubt anymore and now the focus is more on how to do it well, on how to get everyone to interoperate. That is, when a European data space is created for a specific sector, such as agriculture or health, all countries and organisations can share data in the best possible way, so that they can be exchanged through common models and that they are done within trusted environments.

2. In this context, why have standards become so essential?

Josema Alonso: I think it's because of everything we've learned over the years. We have learned that it is necessary for people to be able to have a certain freedom when it comes to developing their own systems. The architecture of the website itself, for example, is how it works, it does not have a central control or anything, but each participant within the website manages things in their own way. But there are clear rules of how those things then have to interact with each other, otherwise it wouldn't work, otherwise we wouldn't be able to load a web page in different browsers or on different mobile phones. So, what we are seeing lately is that there is an increasing attempt to figure out how to reach that type of consensus in a mutual benefit. For example, part of my current work for the European Commission is in the Semantic Interoperability Community, where we manage the creation of uniform models that are used across Europe, definitions of basic standard vocabularies that are used in all systems. In recent years it has also been instrumentalized in a way that supports, let's say, that consensus through regulations that have been issued, for example, at the European level. In recent years we have seen the regulation of data, the regulation of data governance and the regulation of artificial intelligence, things that also try to put a certain order and barriers. It's not that everyone goes through the middle of the mountain, because if not, in the end we won't get anywhere, but we're all going to try to do it by consensus, but we're all going to try to drive within the same road to reach the same destination together. And I think that, from the part of the public administrations, apart from regulating, it is very interesting that they are very transparent in the way it is done. It is the way in which we can all come to see that what is built is built in a certain way, the data models that are transparent, everyone can see them participate in their development. And this is where we are seeing some shortcomings in algorithmic and artificial intelligence systems, where we do not know very well the data they use or where it is hosted. And this is where perhaps we should have a little more influence in the future. But I think that as long as this duality is achieved, of generating consensus and providing a context in which people feel safe developing it, we will continue to move in the right direction.

Carlos Iglesias: If we look at the principles that made the website work in its day, there is also a lot of focus on the community part and leaving an open platform that is developed in the open, with open standards in which everyone could join. The participation of everyone was sought to enrich that ecosystem. And I think that with the data we should think that this is the way to go. In fact, it's kind of also a bit like the concept that I think is behind data spaces. In the end, it is not easy to do something like that. It's very ambitious and we don't see an invention like the web every day.

3. From your perspective, what are the real risks of data getting trapped in opaque infrastructures or models? More importantly, what can we do to prevent it?

Carlos Iglesias: Years ago we saw that there was an attempt to quantify the amount of data that was generated daily. I think that now no one even tries it, because it is on a completely different scale, and on that scale there is only one way to work, which is by automating things. And when we talk about automation, in the end what you need are standards, interoperability, trust mechanisms, etc. If we look ten or fifteen years ago, which were the companies that had the highest share price worldwide, they were companies such as Ford or General Electric. If you look at the top ten worldwide, today there are companies that we all know and use every day, such as Meta, which is the parent company of Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp and others, or Alphabet, which is the parent company of Google. In other words, in fact, I think I'm a little hesitant right now, but probably of the ten largest listed companies in the world, all are dedicated to data. We are talking about a gigantic ecosystem and, in order for this to really work and remain an open ecosystem from which everyone can benefit, the key is standardization.

Josema Alonso: I agree with everything Carlos said and we have to focus on not getting trapped. And above all, from the public administrations there is an essential role to play. I mentioned before about regulation, which sometimes people don't like very much because the regulatory map is starting to be extremely complicated. The European Commission, through an omnibus decree, is trying to alleviate this regulatory complexity and, as an example, in the data regulation itself, which obliges companies that have data to facilitate data portability to their users. It seems to me that it is something essential. We're going to see a lot of changes in that. There are three things that always come to mind; permanent training is needed. This changes every day at an astonishing speed. The volumes of data that are now managed are huge. As Carlos said before, a few days ago I was talking to a person who manages the infrastructure of one of the largest streaming platforms globally and he told me that they are receiving requests for data generated by artificial intelligence in such a large volume in just one week as the entire catalog they have available. So the administration needs to have permanent training on these issues of all kinds, both at the forefront of technology as we have just mentioned, and what we talked about before, how to improve interoperability, how to create better data models, etc. Another is the common infrastructure in Europe, such as the future European digital wallet, which would be the equivalent of the national citizen folder. A super simple example we are dealing with is the birth certificate. It is very complicated to try to integrate the systems of twenty-seven different countries, which in turn have regional governments and which in turn have local governments. So, the more we invest in common infrastructure, both at the semantic level and at the level of the infrastructure itself, the cloud, etc., I think the better we will do. And then the last one, which is the need for distributed but coordinated governance. Each one is governed by certain laws at local, national or European level. It is good that we begin to have more and more coordination in the higher layers and that those higher layers permeate to the lower layers and the systems are increasingly easier to integrate and understand each other. Data spaces are one of the major investments at the European level, where I believe this is beginning to be achieved. So, to summarize three things that are very practical to do: permanent training, investing in common infrastructure and that governance continues to be distributed, but increasingly coordinated.