The carbon footprint is a key indicator for understanding the environmental impact of our actions. It measures the amount of greenhouse gas emissions released into the atmosphere as a result of human activities, most notably the burning of fossil fuels such as oil, natural gas and coal. These gases, which include carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O), contribute to global warming by trapping heat in the earth's atmosphere.

Many actions are being carried out by different organisations to try to reduce the carbon footprint. These include those included in the European Green Pact or the Sustainable Development Goals. But this is an area where every small action counts and, as citizens, we can also contribute to this goal through small changes in our lifestyles.

Moreover, this is an area where open data can have a major impact. In particular, the report "The economic impact of open data: opportunities for value creation in Europe (2020)" highlights how open data has saved the equivalent of 5.8 million tonnes of oil every year in the European Union by promoting greener energy sources. This include 79.6 billion in cost savings on energy bills.

This article reviews some solutions that help us measure our carbon footprint to raise awareness of the situation, as well as useful open data sources .

Calculators to know your carbon footprint

The European Union has a web application where everyone can analyse the life cycle of products and energy consumed in five specific areas (food, mobility, housing, household appliances and household goods), based on 16 environmental impact indicators. The user enters certain data, such as his energy expenditure or the details of his vehicle, and the solution calculates the level of impact. The website also offers recommendations for improving consumption patterns. It was compiled using data from Ecoinvent y Agrifoot-print, as well as different public reports detailed in its methodology.

The UN also launched a similar solution, but with a focus on consumer goods. It allows the creation of product value chains by mapping the materials, processes and transports that have been used for their manufacture and distribution, using a combination of company-specific activity data and secondary data. The emission factors and datasets for materials and processes come from a combination of data sources such as Ecoinvent, the Swedish Environment Institute, DEFRA (UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs), academic papers, etc. The calculator is also linked to the the Platform for carbon footprint offsetting of the United Nations. This allows users of the application to take immediate climate action by contributing to UN green projects.

Looking at Spain, the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge has several tools to facilitate the calculation of the carbon footprint aimed at different audiences: organisations, municipalities and farms. They take into account both direct emissions and indirect emissions from electricity consumption. Among other data sources, it uses information from National Greenhouse Gas Inventory. It also provides an estimate of the carbon dioxide removals generated by an emission reduction project.

Another tool linked to this ministry is ComidaAPrueba, launched by the Fundación Vida Sostenible and aimed at finding out the sustainability of citizens' diets. The mobile application, available for both iOs and Android, allows us to calculate the environmental footprint of our meals to make us aware of the impact of our actions. It also proposes healthy recipes that help us to reduce food waste.

But not all actions of this kind are driven by public bodies or non-profit associations. The fight against the deterioration of our environment is also a niche market offering business opportunities. Private companies also offer solutions for calculating the carbon footprint, such as climate Hero, which is based on multiple data sources.

Data sources to feed carbon footprint calculators

As we have seen, in order to make these calculations, these solutions need to be based on data that allow them to calculate the relationship between certain consumption habits and the emissions generated. To do this, they draw on a variety of data sources, many of which are open. In Spain, for example, we find:

- National Statistics Institute (INE). The INE provides data on atmospheric emissions by branch of activity, as well as for households. It can be filtered by gas type and its equivalence in thousands of tonnes of CO2. It also provides data on the historical evolution of the achievement of carbon footprint reduction targets, which are based on the National Inventories of Emissions to the Atmosphere, prepared by the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge.

- Autonomous Communities. Several regional governments carry out inventories of pollutant emissions into the atmosphere. This is the case of the Basque Country and the Community of Madrid. Some regions also publish open forecast data, such as the Canary Islands, which provides projections of climate change in tourism or drought situations.

Other international data services to consider are:

- EarthData. This service provides full and open access to NASA' s collection of Earth science data to understand and protect our planet. This web provides links to commonly used data on greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, ozone, chlorofluorocarbons and water vapour, as well as information on their environmental impact.

- Eurostat. The Statistical Office of the European Commission regularly publishes estimates of quarterly greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union, broken down by economic activity. The estimates cover all quarters from 2010 to the present.

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). This platform is the EU's knowledge base on sustainable production and consumption. It provides a product life cycle inventory for supply chain analysis. Data from business associations and other sources related to energy carriers, transport and waste management are used.

- Our World in Data. One of the most widely used datasets of this portal contains information on CO2 and greenhouse gas emissions through key metrics. Various primary data sources such as the US Energy Information Agency and The Global Carbon Project have been used for its elaboration. All raw data and scripts are available in their GitHub repository.

These repositories are just a sample, but there are many more sources whit valuable data to help us become more aware of the climate situation we live in and the impact our small day-to-day actions have on our planet. Reducing our carbon footprint is crucial to preserving our environment and ensuring a sustainable future. And only together will we be able to achieve our goals.

Data activism is an increasingly significant citizen practice in the platform era for its growing contribution to democracy, social justice and rights. It is an activism that uses data and data analysis to generate evidence and visualisations with the aim of revealing injustices, improving people's lives and promoting social change.

In the face of the massive use of surveillance data by certain corporations, data activism is exercised by citizens and non-governmental organisations. For example, the organisation Forensic Architecture (FA)a centre at Goldsmiths under the University of London, investigates human rights violations, including state violence, using public, citizen and satellite data, and methodologies such as open source intelligence (known as OSINT). The analysis of data and metadata, the synchronisation of video footage taken by witnesses or journalists, as well as official recordings and documents, allows for the reconstruction of facts and the generation of an alternative narrative about events and crises.

Data activism has attracted the interest of research centres and non-governmental organisations, generating a line of work within the discipline of critical studies. This has allowed us to reflect on the effect of data, platforms and their algorithms on our lives, as well as on the empowerment that is generated when citizens exercise their right to data and use it for the common good.

Image 1: Ecocide in Indonesia (2015)

Source: Forensic Architecture (https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/ecocide-in-indonesia)

Research centres such as Datactive o Data + Feminism Lab have created theory and debates on the practice of data activism. Likewise, organisations such as Algorights -a collaborative network that encourages civil society participation in the field of aI technologies- y AlgorithmWatch -a human rights organisation - generate knowledge, networks and arguments to fight for a world in which algorithms and artificial Intelligence (AI) contribute to justice, democracy and sustainability, rather than undermine them.

This article reviews how data activism emerged, what interest it has sparked in social science, and its relevance in the age of platforms.

History of a practice

The production of maps using citizen data could be one of the first manifestations of data activism as it is now known. A seminal map in the history of data activism was generated by victims and activists with data from the 2010 Haiti earthquakeon the Kenyan platform Ushahidi ("testimony" in Swahili). A community of digital humanitarianscreated the map from other countries and called on victims and their families and acquaintances to share data on what was happening in real time. Within hours, the data was verified and visualised on an interactive map that continued to be updated with more data and was instrumental in assisting the victims on the ground. Today, such mapsare generated whenever a crisis arises, and are enriched with citizen, satellite and camera-equipped drone data to clarify events and generate evidence.

Emerging from movements known as cypherpunk and technopositivism or technoptimism (based on the belief that technology is the answer to humanity's challenges), data activism has evolved as a practice to adopt more critical stances towards technology and the power asymmetries that arise between those who originate and hand over their data, and those who capture and analyse it.

Today, for example, the Ushahidi community map production platform has been used to create data on gender-based violence in Egypt and Syria, and on trusted gynaecologists in India, for example. Today, the invisibilisation and silencing of women is the reason why some organisations are fighting for recognition and a policy of visibility, something that became evident with the #MeToo movement. Feminist data practices seek visibility and critical interpretations of datification(or the transformation of all human and non-human action into measurable data that can be transformed into value). For example, Datos Contra el Feminicidio or Feminicidio.net offer maps and data analysis on femicide in various parts of the world.

The potential for algorithmic empowerment offered by these projects removes barriers to equality by improving the conditions conditions that enable women to solve problems, determine how data is collected and used, and exercise power.

Birth and evolution of a concept

In 2015, Citizen Media Meets Big Data: The Rise of Data Activismwas published, in which, for the first time, data activism was coined and defined as a concept based on practices observed in activists who engage politically with data infrastructure. Data infrastructure includes the data, software, hardware and processes needed to turn data into value. Later, Data activism and social change (London, Palgrave) and Data activism and social change. Alliances, maps, platforms and action for a better world (Madrid: Dykinson) develop analytical frameworks based on real cases that offer ways to analyse other cases.

Accompanying the varied practices that exist within data activism, its study is creating spaces for feminist and post-colonialist research on the consequences of datification. Whereas the chroniclers of history (mainly male sources) defined technology in relation to the value of their productsfeminist data studies consider women as users and designers of technology as users and designers of algorithmic systems and seek to use data for equality, and to move away from capitalist exploitation and its structures of domination.

Data activism is now an established concept in social science. For example, Google Scholar offers more than 2,000 results on "data activism". Several researchers use it as a perspective to analyse various issues. For example, Rajão and Jarke explore environmental activism in Brazil; Gezgin studies critical citizenship and its use of data infrastructure; Lehtiniemi and Haapoja explore data agency and citizen participation; and Scott examines the need for platform users to develop digital surveillance and care for their personal data.

At the heart of these concerns is the concept of data agency, which refers to people not only being aware of the value of their data, but also exercising control over it, determining how it is used and shared. It could be defined as actions and practices related to data infrastructure based on individual and collective reflection and interest. That is, while liking a post would not be considered an action with a high degree of data agency, participating in a hackathon - a collective event in which a computer programme is improved or created - would be. Data agency is based on data literacy, or the degree of knowledge, access to data and data tools, and opportunities for data literacy that people have. Data activism is not possible without a data agency.

In the rapidly evolving landscape of the platform economy, the convergence of data activism, digital rights and data agency has become crucial. Data activism, driven by a growing awareness of the potential misuse of personal data, encourages individuals and collectives to use digital technology for social change, as well as to advocate for greater transparency and accountability on the part of tech giants. As more and more data generation and the use of algorithms shape our lives in areas such as education, employment, social services and health, data activism emerges as a necessity and a right, rather than an option.

____________________________________________________________________

Content prepared by Miren Gutiérrez, PhD and researcher at the University of Deusto, expert in data activism, data justice, data literacy and gender disinformation.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

Young people have consolidated in recent years as the most connected demographic group in the world and are now also the most relevant actors in the new digital economy. One in three internet users across the planet is a child. Furthermore, this trend has been accelerating even more in the current context of health emergencies, in which young people have exponentially increased the time they spend online while being much more active and sharing much more information on social networks. A clear example of the consequences of this incremental use is the need of online teaching, where new challenges are posed in terms of student privacy, while we already know of some initial cases related to problems in the management of fairly worrying data.

On the other hand, young people are more concerned about their privacy than we might initially think. However, they recognise that they have many problems in understanding how and for what purpose the various online services and tools collect and reuse their personal information.

For all these reasons, although in general legislation related to online privacy is still developing throughout the world, there are already several governments that now recognise that children - and minors in general - require special treatment with regard to the privacy of their data as a particularly vulnerable group in the digital context.

Therefore, minors already have a degree of special protection in some of the legislative frameworks of reference in terms of privacy at a global level, as the European (GDPR) or US (COPPA) regulations. For example, both set limits on the general age of legal consent for the processing of personal data (16 years in the GDPR and 13 years in COPPA), as well as providing additional protection measures such as requiring parental consent, limiting the scope of use of such data or using simpler language in the information provided about privacy.

However, the degree of protection we offer children and young people in the online world is not yet comparable to the protection they have in the offline world, and we must therefore continue to make progress in creating safe online spaces that have strong privacy measures and specific features so that minors can feel safe and be truly protected - in addition to continuing to educate both young people and their guardians in good practice in terms of managing personal data.

The Responsible Management of Children's Data (RD4C) initiative, promoted by UNICEF and The GovLab, was born with this objective in mind. The aim of this initiative is to raise awareness of the need to pay special attention to data activities involving children, helping us to better understand the potential risks and improve practices around data collection and analysis in order to mitigate them. To this end, they propose a number of principles that we should follow in the handling of such data:

- Participatory processes: Involving and informing people and groups affected by the use of data for and about children

- Responsibility and accountability: Establishing institutional processes, roles and responsibilities for data processing.

- People-centred: Prioritising the needs and expectations of children and young people, their guardians and their social circles.

- Damage prevention: Assessing potential risks in advance during the stages of the data lifecycle, including collection, storage, preparation, sharing, analysis and use.

- Proportional: Adjusting the extent of data collection and the length of data retention to the purpose initially intended.

- Protection of children's rights: Recognizing the different rights and requirements needed to help children develop to their full potential.

- Purpose-driven: specifying what the data is needed for and how its use can potentially benefit children's lives.

Some governments have also begun to go a step further and favour a higher degree of protection for minors by developing their own guidelines aimed at improving the design of online services. A good example is the code of conduct developed by the UK which - similarly to the R4DC - also calls for the best interests of children themselves, but also introduces a number of service design patterns that include recommendations such as the inclusion of parental controls, limitations on the collection of personal data or restrictions on the use of misleading design patterns that encourage data sharing. Another good example is the technical note published by the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD) for the protection of children on the Internet, which provides detailed recommendations to facilitate parental control in access to online services and applications.

At datos.gob.es, we also want to contribute to the responsible use of data affecting young people, and we also believe in participatory processes. That is why we have included data security and/or privacy issues in the field of education as one of the challenges to be resolved in the next Aporta Challenge. We hope that you will be encouraged to participate and send us all your ideas in this and other areas related to digital education before 18 November.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultan, World Wide Web Foundation.

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

Statistical data is considered high-value data, due to its broad benefits to society, the environment, and the economy. Statistical data provides us with information on demographic and economic indicators (for example, data on GDP, educational level or population age), essential information when making decisions and formulating policies and strategies.

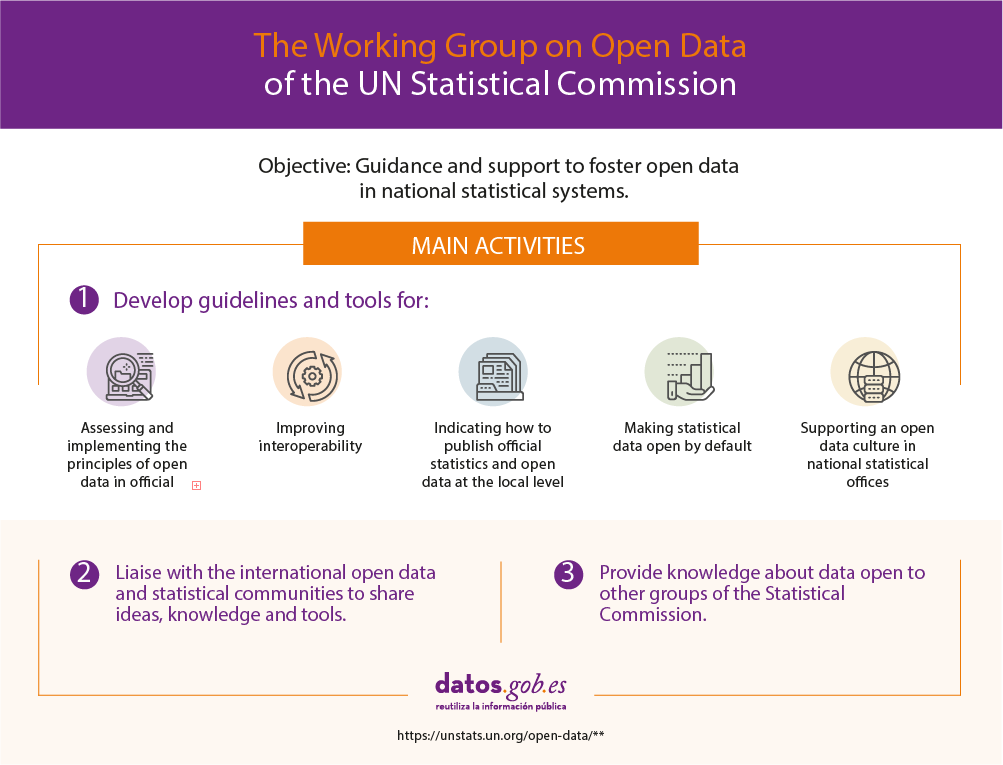

Such is its importance for society as a whole that the UN Statistical Commission created in 2018 an Working Group on Open Data, focused on providing support for the application of open data principles to statistical information, so that its universal and free access is provided. This working group is made up of representatives from different countries, international organizations and associations, such as the World Bank, Open Data Watch, the International Statistical Institute or representatives of the UN itself through agencies such as FAO.

In early March, this group produced a report to guide national statistical offices on open data practices in the production of official statistics. This document is divided into two sections:

• A background document on the application of open data in national statistical offices

• A background document on local level statistics in the form of open data

Let's see the conclusions of each of them.

The application of open data in national statistical offices

The report offers guidelines in the following areas:

- Default open data: The document focuses on the legal aspects of default open data, emphasizing the need for open licensing standards. According to the “Open Data Inventory”, in the period 2018-2019 only 14 out of 180 analysed countries published all their data with an open license. There are many types of internationally recognized licenses. The most common are the Creative Commons and Open Data Commons, although many countries tend to customize them. The report recommends approving an international open license in its original form or preparing a custom license, but conforming to the guidelines formulated by Open Definition. In addition to open licenses, countries also need to have a legal framework with laws on access to information and accountability.

- User-centered designs: The report highlights the need to involve users in the development of platforms and the dissemination of data to ensure that their needs are met. Some of the mechanisms that can be used are conducting surveys, interviews or focus groups. It is also necessary to measure the use of data through website analysis in order to take decisions that increase its use. Given that all countries need to create user participation strategies, it would be advisable to encourage the exchange of templates and guidelines or the holding of joint workshops.

- National reporting platforms: Data platforms must be based on four principles: clarity, adequacy, sustainability and interoperability. For these principles to be fulfilled, it is necessary to promote coordination and cooperation within the national statistical system, and the national statistical office should take the lead.

- Correlation of the Generic Model of Statistical Institutional Processes with interoperability guidelines: To facilitate the different offices to share innovative approaches regarding the collection and dissemination of statistics, it is appropriate to have a framework that includes good practices and standardized terminology. The Generic Model of Statistical Institutional Processes describes the set of actions necessary to produce official statistics, guaranteeing constant improvement. These stages are: a) specify needs; b) design; c) build; d) collect; e) process; f) analyse; g) disseminate; and h) evaluate. In order to incorporate interoperability into the Model, the most relevant interoperability practices should be incorporated into the different design phases.

- Development of an open data culture: The adoption of open data principles in the daily life of statistical institutions can mean a change of mentality. Sometimes you have to "convince" about the need to open this type of information. For this reason, it is essential to carry out internal and external communication actions, analyse existing capacities and carry out training tasks accordingly, and establish responsibilities.

Local level statistics in the form of open data

In addition to having national statistical offices, it is advisable to launch local initiatives that can provide information on specific geographic spaces such as neighbourhoods, rural areas, or census and electoral districts. This information may show disparity between regions and help in the formulation of local policies. It is also useful for civil society, the private sector and NGOs to make better decisions.

In order for comparisons to be made, the report recommends that these data be produced and disseminated following the same guidelines across the country. In addition, it urges national offices to investigate which statistical content is of most interest to users and to provide a series of recommendations, ranging from disclosure mechanisms to the most useful visualization tools. The implementation could be carried out with a gradual approach, where interaction between the different actors involved is encouraged.

The report also refers to the background document presented at the fiftieth session of the Statistical Commission, which includes guidance on understanding open data practices in official statistics. A document worth reviewing when launching such an initiative.

In short, we are dealing with a type of data of great importance, which must be shared with society through an ecosystem of publishers and always respecting the balance between openness and privacy.