Did you know that Spain created the first state agency specifically dedicated to the supervision of artificial intelligence (AI) in 2023? Even anticipating the European Regulation in this area, the Spanish Agency for the Supervision of Artificial Intelligence (AESIA) was born with the aim of guaranteeing the ethical and safe use of AI, promoting responsible technological development.

Among its main functions is to ensure that both public and private entities comply with current regulations. To this end, it promotes good practices and advises on compliance with the European regulatory framework, which is why it has recently published a series of guides to ensure the consistent application of the European AI regulation.

In this post we will delve into what the AESIA is and we will learn relevant details of the content of the guides.

What is AESIA and why is it key to the data ecosystem?

The AESIA was created within the framework of Axis 3 of the Spanish AI Strategy. Its creation responds to the need to have an independent authority that not only supervises, but also guides the deployment of algorithmic systems in our society.

Unlike other purely sanctioning bodies, the AESIA is designed as an intelligence Think & Do, i.e. an organisation that investigates and proposes solutions. Its practical usefulness is divided into three aspects:

- Legal certainty: Provides clear frameworks for businesses, especially SMEs, to know where to go when innovating.

- International benchmark: it acts as the Spanish interlocutor before the European Commission, ensuring that the voice of our technological ecosystem is heard in the development of European standards.

- Citizen trust: ensures that AI systems used in public services or critical areas respect fundamental rights, avoiding bias and promoting transparency.

Since datos.gob.es, we have always defended that the value of data lies in its quality and accessibility. The AESIA complements this vision by ensuring that, once data is transformed into AI models, its use is responsible. As such, these guides are a natural extension of our regular resources on data governance and openness.

Resources for the use of AI: guides and checklists

The AESIA has recently published materials to support the implementation and compliance with the European Artificial Intelligence regulations and their applicable obligations. Although they are not binding and do not replace or develop existing regulations, they provide practical recommendations aligned with regulatory requirements pending the adoption of harmonised implementing rules for all Member States.

They are the direct result of the Spanish AI Regulatory Sandbox pilot. This sandbox allowed developers and authorities to collaborate in a controlled space to understand how to apply European regulations in real-world use cases.

It is essential to note that these documents are published without prejudice to the technical guides that the European Commission is preparing. Indeed, Spain is serving as a "laboratory" for Europe: the lessons learned here will provide a solid basis for the Commission's working group, ensuring consistent application of the regulation in all Member States.

The guides are designed to be a complete roadmap, from the conception of the system to its monitoring once it is on the market.

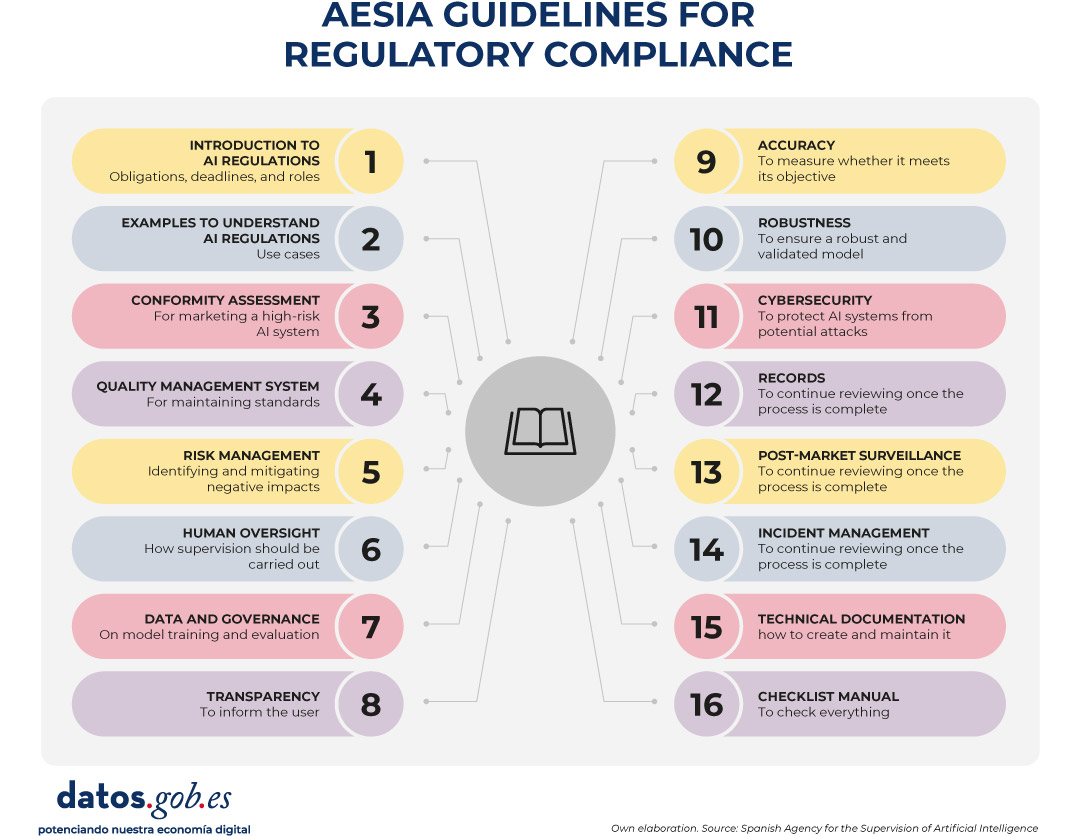

Figure 1. AESIA guidelines for regulatory compliance. Source: Spanish Agency for the Supervision of Artificial Intelligence

- 01. Introductory to the AI Regulation: provides an overview of obligations, implementation deadlines and roles (suppliers, deployers, etc.). It is the essential starting point for any organization that develops or deploys AI systems.

- 02. Practice and examples: land legal concepts in everyday use cases (e.g., is my personnel selection system a high-risk AI?). It includes decision trees and a glossary of key terms from Article 3 of the Regulation, helping to determine whether a specific system is regulated, what level of risk it has, and what obligations are applicable.

- 03. Conformity assessment: explains the technical steps necessary to obtain the "seal" that allows a high-risk AI system to be marketed, detailing the two possible procedures according to Annexes VI and VII of the Regulation as valuation based on internal control or evaluation with the intervention of a notified body.

- 04. Quality management system: defines how organizations must structure their internal processes to maintain constant standards. It covers the regulatory compliance strategy, design techniques and procedures, examination and validation systems, among others.

- 05. Risk management: it is a manual on how to identify, evaluate and mitigate possible negative impacts of the system throughout its life cycle.

- 06. Human surveillance: details the mechanisms so that AI decisions are always monitorable by people, avoiding the technological "black box". It establishes principles such as understanding capabilities and limitations, interpretation of results, authority not to use the system or override decisions.

- 07. Data and data governance: addresses the practices needed to train, validate, and test AI models ensuring that datasets are relevant, representative, accurate, and complete. It covers data management processes (design, collection, analysis, labeling, storage, etc.), bias detection and mitigation, compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation, data lineage, and design hypothesis documentation, being of particular interest to the open data community and data scientists.

- 08. Transparency: establishes how to inform the user that they are interacting with an AI and how to explain the reasoning behind an algorithmic result.

- 09. Accuracy: Define appropriate metrics based on the type of system to ensure that the AI model meets its goal.

- 10. Robustness: Provides technical guidance on how to ensure AI systems operate reliably and consistently under varying conditions.

- 11. Cybersecurity: instructs on protection against threats specific to the field of AI.

- 12. Logs: defines the measures to comply with the obligations of automatic registration of events.

- 13. Post-market surveillance: documents the processes for executing the monitoring plan, documentation and analysis of data on the performance of the system throughout its useful life.

- 14. Incident management: describes the procedure for reporting serious incidents to the competent authorities.

- 15. Technical documentation: establishes the complete structure that the technical documentation must include (development process, training/validation/test data, applied risk management, performance and metrics, human supervision, etc.).

- 16. Requirements Guides Checklist Manual: explains how to use the 13 self-diagnosis checklists that allow compliance assessment, identifying gaps, designing adaptation plans and prioritizing improvement actions.

All guides are available here and have a modular structure that accommodates different levels of knowledge and business needs.

The self-diagnostic tool and its advantages

In parallel, the AESIA publishes material that facilitates the translation of abstract requirements into concrete and verifiable questions, providing a practical tool for the continuous assessment of the degree of compliance.

These are checklists that allow an entity to assess its level of compliance autonomously.

The use of these checklists provides multiple benefits to organizations. First, they facilitate the early identification of compliance gaps, allowing organizations to take corrective action prior to the commercialization or commissioning of the system. They also promote a systematic and structured approach to regulatory compliance. By following the structure of the rules of procedure, they ensure that no essential requirement is left unassessed.

On the other hand, they facilitate communication between technical, legal and management teams, providing a common language and a shared reference to discuss regulatory compliance. And finally, checklists serve as a documentary basis for demonstrating due diligence to supervisory authorities.

We must understand that these documents are not static. They are subject to an ongoing process of evaluation and review. In this regard, the EASIA continues to develop its operational capacity and expand its compliance support tools.

From the open data platform of the Government of Spain, we invite you to explore these resources. AI development must go hand in hand with well-governed data and ethical oversight.

To speak of the public domain is to speak of free access to knowledge, shared culture and open innovation. The concept has become a key piece in understanding how information circulates and how the common heritage of humanity is built.

In this post we will explore what the public domain means and show you examples of repositories where you can discover and enjoy works that are already part of everyone.

What is the public domain?

Surely at some point in your life you have seen the image of Mickey Mouse Handling the helm on a steamboat. A characteristic image of the Disney company that you can now use freely in your own works. This is because this first version of Mickey (Steamboat Willie, 1928) entered the public domain in January 2024 -be careful, only the version of that date is "free", subsequent adaptations do continue to be protected, as we will explain later-.

When we talk about the public domain, we refer to the body of knowledge, i nformation, works and creations (books, music, films, photos, software, etc.) that are not protected by copyright. Because of this , anyone can reproduce, copy, adapt and distribute them without having to ask permission or pay licenses. However, the moral rights of the author must always be respected, which are inalienable and do not expire. These rights include always respecting the authorship and integrity of the work*.

The public domain, therefore, shapes the cultural space where works become the common heritage of society, which entails multiple benefits:

- Free access to culture and knowledge: any citizen can read, watch, listen to or download these works without paying for licenses or subscriptions. This favors education, research and universal access to culture.

- Preservation of memory and heritage: the public domain ensures that an important part of our history, science and art remains accessible to present and future generations, without being limited by legal restrictions.

- Encourages creativity and innovation: artists, developers, companies, etc. can reuse and mix works from the public domain to create new products (such as adaptations, new editions, video games, comics, etc.) without fear of infringing rights.

- Technological boost: archives, museums and libraries can freely digitise and disseminate their holdings in the public domain, creating opportunities for digital projects and the development of new tools. For example, these works can be used to train artificial intelligence models and natural language processing tools.

What works and elements belong to the public domain, according to Spanish law?

In the public domain we find both content whose copyright has expired and content that has never been protected. Let's see what Spanish legislation says about it:

Works whose copyright protection has expired.

To know if a work belongs to the public domain, we must look at the date of the death of its author. In this sense, in Spain, there is a turning point: 1987. From that year on, and according to the intellectual property law, artistic works enter the public domain 70 years after the death of their author. However, perpetrators who died before that year are subject to the 1879 Law, where the term was generally 80 years – with exceptions.

Only "original literary, artistic or scientific" creations that involve a sufficient level of creativity are protected, regardless of their medium (paper, digital, audiovisual, etc.). This includes books, musical compositions, theatrical, audiovisual or pictorial works and sculptures to graphics, maps and designs related to topography, geography and science or computer programs, among others.

It should be noted that translations and adaptations, revisions, updates and annotations; compendiums, summaries and extracts; musical arrangements, collections of other people's works, such as anthologies or any transformations of a literary, artistic or scientific work, are also subject to intellectual property. Therefore, a recent adaptation of Don Quixote will have its own protection.

Works that are not eligible for copyright protection.

As we saw, not everything that is produced can be covered by copyright, some examples are:

- Official documents: laws, decrees, judgments and other official texts are not subject to copyright. They are considered too relevant to public life to be restricted, and are therefore in the public domain from the moment of publication.

- Works voluntarily transferred: The rights holders themselves can decide to release their works before the legal term expires. For this there are tools such as the license Creative Commons CC0 , which makes it possible to renounce protection and make the work directly available to everyone.

- Facts and Information: Copyright does not cover facts or data. Information and events are common heritage and can be used freely by anyone.

Europeana and its defence of the public domain

Europeana is Europe's great digital library, a project promoted by the European Union that brings together millions of cultural resources from archives, museums and libraries throughout the territory. Its mission is to facilitate free and open access to European cultural heritage, and in that sense the public domain is at the heart of it. Europeana advocates that works that have lost their copyright protection should remain unrestricted, even when digitized, because they are part of the common heritage of humanity.

As a result of its commitment, it has recently updated its Public Domain Charter, which includes a series of essential principles and guidelines for a robust and vibrant public domain in the digital environment. Among other issues, it mentions how technological advances and regulatory changes have expanded the possibilities of access to cultural heritage, but have also generated risks for the availability and reuse of materials in the public domain. Therefore, it proposes eight measures to protect and strengthen the public domain:

- Advocate against extending the terms or scope of copyright, which limits citizens' access to shared culture.

- Oppose attempts to undue control over free materials, avoiding licenses, fees, or contractual restrictions that reconstitute rights.

- Ensure that digital reproductions do not generate new layers of protection, including photos or 3D models, unless they are original creations.

- Avoid contracts that restrict reuse: Financing digitalisation should not translate into legal barriers.

- Clearly and accurately label works in the public domain, providing data such as author and date to facilitate identification.

- Balancing access with other legitimate interests, respecting laws, cultural values and the protection of vulnerable groups.

- Safeguard the availability of heritage, in the face of threats such as conflicts, climate change or the fragility of digital platforms, promoting sustainable preservation.

- To offer high-quality, reusable reproductions and metadata, in open, machine-readable formats, to enhance their creative and educational use.

Other platforms to access works in the public domain

In addition to Europeana, in Spain we have an ecosystem of projects that make cultural heritage in the public domain available to everyone:

- The National Library of Spain (BNE) plays a key role: every year it publishes the list of Spanish authors who enter the public domain and offers access to their digitized works through BNE Digital, a portal that allows you to consult manuscripts, books, engravings and other historical materials. Thus, we can find works by authors of the stature of Antonio Machado or Federico García Lorca. In addition, the BNE publishes the dataset with information on authors in the public domain in the open air.

- The Virtual Library of Bibliographic Heritage (BVPB), promoted by the Ministry of Culture, brings together thousands of digitized ancient works, ensuring that fundamental texts and materials of our literary and scientific history can be preserved and reused without restrictions. It includes digital facsimile reproductions of manuscripts, printed books, historical photographs, cartographic materials, sheet music, maps, etc.

- Hispana acts as a large national aggregator by connecting digital collections from Spanish archives, libraries, and museums, offering unified access to materials that are part of the public domain. To do this, it collects and makes accessible the metadata of digital objects, allowing these objects to be viewed through links that lead to the pages of the owner institutions.

Together, all these initiatives reinforce the idea that the public domain is not an abstract concept, but a living and accessible resource that expands every year and that allows our culture to continue circulating, inspiring and generating new forms of knowledge.

Thanks to Europeana, BNE Digital, the BVPB, Hispana and many other projects of this type, today we have the possibility of accessing an immense cultural heritage that connects us with our past and propels us towards the future. Each work that enters the public domain expands opportunities for learning, innovation and collective enjoyment, reminding us that culture, when shared, multiplies.

*In accordance with the Intellectual Property Law, the integrity of the work refers to preventing any distortion, modification, alteration or attack against it that damages its legitimate interests or damages its reputation.

On 19 November, the European Commission presented the Data Union Strategy, a roadmap that seeks to consolidate a robust, secure and competitive European data ecosystem. This strategy is built around three key pillars: expanding access to quality data for artificial intelligence and innovation, simplifying the existing regulatory framework, and protecting European digital sovereignty. In this post, we will explain each of these pillars in detail, as well as the implementation timeline of the plan planned for the next two years.

Pillar 1: Expanding access to quality data for AI and innovation

The first pillar of the strategy focuses on ensuring that companies, researchers and public administrations have access to high-quality data that allows the development of innovative applications, especially in the field of artificial intelligence. To this end, the Commission proposes a number of interconnected initiatives ranging from the creation of infrastructure to the development of standards and technical enablers. A series of actions are established as part of this pillar: the expansion of common European data spaces, the development of data labs, the promotion of the Cloud and AI Development Act, the expansion of strategic data assets and the development of facilitators to implement these measures.

1.1 Extension of the Common European Data Spaces (ECSs)

Common European Data Spaces are one of the central elements of this strategy:

-

Planned investment: 100 million euros for its deployment.

-

Priority sectors: health, mobility, energy, (legal) public administration and environment.

-

Interoperability: SIMPL is committed to interoperability between data spaces with the support of the European Data Spaces Support Center (DSSC).

-

Key Applications:

-

European Health Data Space (EHDS): Special mention for its role as a bridge between health data systems and the development of AI.

-

New Defence Data Space: for the development of state-of-the-art systems, coordinated by the European Defence Agency.

-

1.2 Data Labs: the new ecosystem for connecting data and AI development

The strategy proposes to use Data Labs as points of connection between the development of artificial intelligence and European data.

These labs employ data pooling, a process of combining and sharing public and restricted data from multiple sources in a centralized repository or shared environment. All this facilitates access and use of information. Specifically, the services offered by Data Labs are:

-

Makes it easy to access data.

-

Technical infrastructure and tools.

-

Data pooling.

-

Data filtering and labeling

-

Regulatory guidance and training.

-

Bridging the gap between data spaces and AI ecosystems.

Implementation plan:

-

First phase: the first Data Labs will be established within the framework of AI Factories (AI gigafactories), offering data services to connect AI development with European data spaces.

-

Sectoral Data Labs: will be established independently in other areas to cover specific needs, for example, in the energy sector.

-

Self-sustaining model: It is envisaged that the Data Labs model can be deployed commercially, making it a self-sustaining ecosystem that connects data and AI.

1.3 Cloud and AI Development Act: boosting the sovereign cloud

To promote cloud technology, the Commission will propose this new regulation in the first quarter of 2026. There is currently an open public consultation in which you can participate here.

1.4 Strategic data assets: public sector, scientific, cultural and linguistic resources

On the one hand, in 2026 it will be proposed to expand the list of high-value data in English or HVDS to include legal, judicial and administrative data, among others. And on the other hand, the Commission will map existing bases and finance new digital infrastructure.

1.5 Horizontal enablers: synthetic data, data pooling, and standards

The European Commission will develop guidelines and standards on synthetic data and advanced R+D in techniques for its generation will be funded through Horizon Europe.

Another issue that the EU wants to promote is data pooling, as we explained above. Sharing data from early stages of the production cycle can generate collective benefits, but barriers persist due to legal uncertainty and fear of violating competition rules. Its purpose? Make data pooling a reliable and legally secure option to accelerate progress in critical sectors.

Finally, in terms of standardisation, the European standardisation organisations (CEN/CENELEC) will be asked to develop new technical standards in two key areas: data quality and labelling. These standards will make it possible to establish common criteria on how data should be to ensure its reliability and how it should be labelled to facilitate its identification and use in different contexts.

Pillar 2: Regulatory simplification

The second pillar addresses one of the challenges most highlighted by companies and organisations: the complexity of the European regulatory framework on data. The strategy proposes a series of measures aimed at simplifying and consolidating existing legislation.

2.1 Derogations and regulatory consolidation: towards a more coherent framework

The aim is to eliminate regulations whose functions are already covered by more recent legislation, thus avoiding duplication and contradictions. Firstly, the Free Flow of Non-Personal Data Regulation (FFoNPD) will be repealed, as its functions are now covered by the Data Act. However, the prohibition of unjustified data localisation, a fundamental principle for the Digital Single Market, will be explicitly preserved.

Similarly, the Data Governance Act (European Data Governance Regulation or DGA) will be eliminated as a stand-alone rule, migrating its essential provisions to the Data Act. This move simplifies the regulatory framework and also eases the administrative burden: obligations for data intermediaries will become lighter and more voluntary.

As for the public sector, the strategy proposes an important consolidation. The rules on public data sharing, currently dispersed between the DGA and the Open Data Directive, will be merged into a single chapter within the Data Act. This unification will facilitate both the application and the understanding of the legal framework by public administrations.

2.2 Cookie reform: balancing protection and usability

Another relevant detail is the regulation of cookies, which will undergo a significant modernization, being integrated into the framework of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The reform seeks a balance: on the one hand, low-risk uses that currently generate legal uncertainty will be legalized; on the other, consent banners will be simplified through "one-click" systems. The goal is clear: to reduce the so-called "user fatigue" in the face of the repetitive requests for consent that we all know when browsing the Internet.

2.3 Adjustments to the GDPR to facilitate AI development

The General Data Protection Regulation will also be subject to a targeted reform, specifically designed to release data responsibly for the benefit of the development of artificial intelligence. This surgical intervention addresses three specific aspects:

-

It clarifies when legitimate interest for AI model training may apply.

-

It defines more precisely the distinction between anonymised and pseudonymised data, especially in relation to the risk of re-identification.

-

It harmonises data protection impact assessments, facilitating their consistent application across the Union.

2. 4 Implementation and Support for the Data Act

The recently approved Data Act will be subject to adjustments to improve its application. On the one hand, the scope of business-to-government ( B2G) data sharing is refined, strictly limiting it to emergency situations. On the other hand, the umbrella of protection is extended: the favourable conditions currently enjoyed by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) will also be extended to medium-sized companies or small mid-caps, those with between 250 and 749 employees.

To facilitate the practical implementation of the standard, a model contractual clause for data exchange has already been published , thus providing a template that organizations can use directly. In addition, two additional guides will be published during the first quarter of 2026: one on the concept of "reasonable compensation" in data exchanges, and another aimed at clarifying the key definitions of the Data Act that may generate interpretative doubts.

Aware that SMEs may struggle to navigate this new legal framework, a Legal Helpdesk will be set up in the fourth quarter of 2025. This helpdesk will provide direct advice on the implementation of the Data Act, giving priority precisely to small and medium-sized enterprises that lack specialised legal departments.

2.5 Evolving governance: towards a more coordinated ecosystem

The governance architecture of the European data ecosystem is also undergoing significant changes. The European Data Innovation Board (EDIB) evolves from a primarily advisory body to a forum for more technical and strategic discussions, bringing together both Member States and industry representatives. To this end, its articles will be modified with two objectives: to allow the inclusion of the competent authorities in the debates on Data Act, and to provide greater flexibility to the European Commission in the composition and operation of the body.

In addition, two additional mechanisms of feedback and anticipation are articulated. The Apply AI Alliance will channel sectoral feedback, collecting the specific experiences and needs of each industry. For its part, the AI Observatory will act as a trend radar, identifying emerging developments in the field of artificial intelligence and translating them into public policy recommendations. In this way, a virtuous circle is closed where politics is constantly nourished by the reality of the field.

Pillar 3: Protecting European data sovereignty

The third pillar focuses on ensuring that European data is treated fairly and securely, both inside and outside the Union's borders. The intention is that data will only be shared with countries with the same regulatory vision.

3.1 Specific measures to protect European data

-

Publication of guides to assess the fair treatment of EU data abroad (Q2 2026):

-

Publication of the Unfair Practices Toolbox (Q2 2026):

-

Unjustified location.

-

Exclusion.

-

Weak safeguards.

-

The data leak.

-

-

Taking measures to protect sensitive non-personal data.

All these measures are planned to be implemented from the last quarter of 2025 and throughout 2026 in a progressive deployment that will allow a gradual and coordinated adoption of the different measures, as established in the Data Union Strategy.

In short, the Data Union Strategy represents a comprehensive effort to consolidate European leadership in the data economy. To this end, data pooling and data spaces in the Member States will be promoted, Data Labs and AI gigafactories will be committed to and regulatory simplification will be encouraged.

The 17th International Conference on the Reuse of Public Sector Information will be held on December 3 in Madrid. The Multisectoral Association of Information (ASEDIE) organizes this event every year, which in its new edition will take place at the Ministry for Digital Transformation and Public Function in Madrid. Under the slogan "When the standard is not enough: inequality in the application of data regulations", the current challenges around the reuse of public information and the need for agile and effective regulatory frameworks will be addressed.

Regulatory complexity, a challenge to be addressed

This event brings together national and European experts to address the reuse of data as a driver of innovation. Specifically, this year's edition focuses on the need to advance in a regulation that promotes a culture of openness in all administrations, avoiding regulatory fragmentation and ensuring that access to public information translates into a true economic and social value.

Through various presentations and round tables, some of the great current challenges in this area will be addressed: from regulatory simplification to facilitate the reuse of information to open government as a real practice.

The program of the Conference

The event will offer a comprehensive vision of how to move towards a fairer, more open and competitive information ecosystem.

The reception for attendees will take place between 09:00 and 09:30. At that time, the event will begin with the welcome and inauguration, which will be given by Ruth del Campo, general director of data (Secretary of State for Digitalization and Artificial Intelligence). It will be followed by two presentations by the Permanent Representation of Spain to the European Union, by Miguel Valle del Olmo, Minister of Digital Transformation, and Almudena Darias de las Heras, Minister of Justice.

Throughout the day there will be three round tables:

- 10:15 – 10:45. Roundtable I: Regulatory simplification and legal certainty: Pillars for an agile and efficient framework. Moderated by Ignacio Jiménez, president of ASEDIE, it will feature the participation of Ruth del Campo and Meritxell Borràs i Solé, director of the Catalan Authority for the Protection of Dades.

- 10:45 – 11:45. Table II: Transparency and Open Government: from theory to practice. Four participants will share their vision and experience in the field: Carmen Cabanillas, Director General of Public Governance (Secretary of State for Public Administration), José Luis Rodríguez Álvarez, President of the Council of Transparency and Good Governance, José Máximo López Vilaboa, Director General of Transparency and Good Governance (Junta de Castilla y León) and Ángela Pérez Brunete, Director General of Transparency and Quality (Madrid City Council). The conversation will be moderated by Manuel Hurtado, member of the Board of Directors of ASEDIE.

- 12:35 – 13:35. Table III: Open and transparent registries. Prevent money laundering without slowing down competitiveness. Under the moderation of Valentín Arce, vice-president of ASEDIE, a conversation will take place led by Antonio Fuentes Paniagua, deputy director general of Notaries and Registries (Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts Antonio), Andrés Martínez Calvo, Consultant of the Centralised Prevention Body (General Council of Notaries), Carlos Balmisa, technical general secretary of the Association of Property and Commercial Registrars, and José Luis Perea, general secretary of ATA Autónomos.

During the morning, the following items will also be delivered:

- The UNE 0080 certification (Guide to the evaluation of Data Quality Governance, Management and Management). This specification develops a homogeneous framework for assessing an organization's maturity with respect to data processing. Find out more about the UNE specifications related to data in this article.

- The ASEDIE 2025 Award. This international award recognizes each year individuals, companies or institutions that stand out for their contribution to the innovation and development of the infomediary sector. To make visible projects that promote the reuse of public sector information (RISP), highlighting its role in the development of both the Spanish and global economy. You can meet the winners in previous editions here.

The event will end at 1:45 p.m., with a few words from Ignacio Jiménez.

You can see the detailed program on the ASEDIE website.

How to Attend

The 17th ASEDIE Conference is an essential event for those working in the field of information reuse, transparency and data-based innovation.

This year's event can only be attended in person at the Ministry for Digital Transformation and Public Function (c/ Mármol, 2, Parque Empresarial Rio 55, 28005, Madrid). It is necessary to register through their website.

The convergence between open data, artificial intelligence and environmental sustainability poses one of the main challenges for the digital transformation model that is being promoted at European level. This interaction is mainly materialized in three outstanding manifestations:

-

The opening of high-value data directly related to sustainability, which can help the development of artificial intelligence solutions aimed at climate change mitigation and resource efficiency.

-

The promotion of the so-called green algorithms in the reduction of the environmental impact of AI, which must be materialized both in the efficient use of digital infrastructure and in sustainable decision-making.

-

The commitment to environmental data spaces, generating digital ecosystems where data from different sources is shared to facilitate the development of interoperable projects and solutions with a relevant impact from an environmental perspective.

Below, we will delve into each of these points.

High-value data for sustainability

Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on open data and re-use of public sector information introduced for the first time the concept of high-value datasets, defined as those with exceptional potential to generate social, economic and environmental benefits. These sets should be published free of charge, in machine-readable formats, using application programming interfaces (APIs) and, where appropriate, be available for bulk download. A number of priority categories have been identified for this purpose, including environmental and Earth observation data.

This is a particularly relevant category, as it covers both data on climate, ecosystems or environmental quality, as well as those linked to the INSPIRE Directive, which refer to certainly diverse areas such as hydrography, protected sites, energy resources, land use, mineral resources or, among others, those related to areas of natural hazards, including orthoimages.

These data are particularly relevant when it comes to monitoring variables related to climate change, such as land use, biodiversity management taking into account the distribution of species, habitats and protected sites, monitoring of invasive species or the assessment of natural risks. Data on air quality and pollution are crucial for public and environmental health, so access to them allows exhaustive analyses to be carried out, which are undoubtedly relevant for the adoption of public policies aimed at improving them. The management of water resources can also be optimized through hydrography data and environmental monitoring, so that its massive and automated treatment is an inexcusable premise to face the challenge of the digitalization of water cycle management.

Combining it with other quality environmental data facilitates the development of AI solutions geared towards specific climate challenges. Specifically, they allow predictive models to be trained to anticipate extreme phenomena (heat waves, droughts, floods), optimize the management of natural resources or monitor critical environmental indicators in real time. It also makes it possible to promote high-impact economic projects, such as the use of AI algorithms to implement technological solutions in the field of precision agriculture, enabling the intelligent adjustment of irrigation systems, the early detection of pests or the optimization of the use of fertilizers.

Green algorithms and digital responsibility: towards sustainable AI

Training and deploying AI systems, particularly general-purpose models and large language models, involves significant energy consumption. According to estimates by the International Energy Agency, data centers accounted for around 1.5% of global electricity consumption in 2024. This represents a growth of around 12% per year since 2017, more than four times faster than the rate of total electricity consumption. Data center power consumption is expected to double to around 945 TWh by 2030.

Against this backdrop, green algorithms are an alternative that must necessarily be taken into account when it comes to minimising the environmental impact posed by the implementation of digital technology and, specifically, AI. In fact, both the European Data Strategy and the European Green Deal explicitly integrate digital sustainability as a strategic pillar. For its part, Spain has launched a National Green Algorithm Programme, framed in the 2026 Digital Agenda and with a specific measure in the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy.

One of the main objectives of the Programme is to promote the development of algorithms that minimise their environmental impact from conception ( green by design), so the requirement of exhaustive documentation of the datasets used to train AI models – including origin, processing, conditions of use and environmental footprint – is essential to fulfil this aspiration. In this regard, the Commission has published a template to help general-purpose AI providers summarise the data used for the training of their models, so that greater transparency can be demanded, which, for the purposes of the present case, would also facilitate traceability and responsible governance from an environmental perspective. as well as the performance of eco-audits.

The European Green Deal Data Space

It is one of the common European data spaces contemplated in the European Data Strategy that is at a more advanced stage, as demonstrated by the numerous initiatives and dissemination events that have been promoted around it. Traditionally, access to environmental information has been one of the areas with the most favourable regulation, so that with the promotion of high-value data and the firm commitment to the creation of a European area in this area, there has been a very remarkable qualitative advance that reinforces an already consolidated trend in this area.

Specifically, the data spaces model facilitates interoperability between public and private open data, reducing barriers to entry for startups and SMEs in sectors such as smart forest management, precision agriculture or, among many other examples, energy optimization. At the same time, it reinforces the quality of the data available for Public Administrations to carry out their public policies, since their own sources can be contrasted and compared with other data sets. Finally, shared access to data and AI tools can foster collaborative innovation initiatives and projects, accelerating the development of interoperable and scalable solutions.

However, the legal ecosystem of data spaces entails a complexity inherent in its own institutional configuration, since it brings together several subjects and, therefore, various interests and applicable legal regimes:

-

On the one hand, public entities, which have a particularly reinforced leadership role in this area.

-

On the other hand, private entities and citizens, who can not only contribute their own datasets, but also offer digital developments and tools that value data through innovative services.

-

And, finally, the providers of the infrastructure necessary for interaction within the space.

Consequently, advanced governance models are essential to deal with this complexity, reinforced by technological innovation and especially AI, since the traditional approaches of legislation regulating access to environmental information are certainly limited for this purpose.

Towards strategic convergence

The convergence of high-value open data, responsible green algorithms and environmental data spaces is shaping a new digital paradigm that is essential to address climate and ecological challenges in Europe that requires a robust and, at the same time, flexible legal approach. This unique ecosystem not only allows innovation and efficiency to be promoted in key sectors such as precision agriculture or energy management, but also reinforces the transparency and quality of the environmental information available for the formulation of more effective public policies.

Beyond the current regulatory framework, it is essential to design governance models that help to interpret and apply diverse legal regimes in a coherent manner, that protect data sovereignty and, ultimately, guarantee transparency and responsibility in the access and reuse of environmental information. From the perspective of sustainable public procurement, it is essential to promote procurement processes by public entities that prioritise technological solutions and interoperable services based on open data and green algorithms, encouraging the choice of suppliers committed to environmental responsibility and transparency in the carbon footprints of their digital products and services.

Only on the basis of this approach can we aspire to make digital innovation technologically advanced and environmentally sustainable, thus aligning the objectives of the Green Deal, the European Data Strategy and the European approach to AI.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, professor at the University of Murcia and coordinator of the Innovation, Law and Technology Research Group (iDerTec). The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is transforming society, the economy and public services at an unprecedented speed. This revolution brings enormous opportunities, but also challenges related to ethics, security and the protection of fundamental rights. Aware of this, the European Union approved the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), in force since August 1, 2024, which establishes a harmonized and pioneering framework for the development, commercialization and use of AI systems in the single market, fostering innovation while protecting citizens.

A particularly relevant area of this regulation is general-purpose AI models (GPAI), such as large language models (LLMs) or multimodal models, which are trained on huge volumes of data from a wide variety of sources (text, images and video, audio and even user-generated data). This reality poses critical challenges in intellectual property, data protection and transparency on the origin and processing of information.

To address them, the European Commission, through the European AI Office, has published the Template for the Public Summary of Training Content for general-purpose AI models: a standardized format that providers will be required to complete and publish to summarize key information about the data used in training. From 2 August 2025, any general-purpose model placed on the market or distributed in the EU must be accompanied by this summary; models already on the market have until 2 August 2027 to adapt. This measure materializes the AI Act's principle of transparency and aims to shed light on the "black boxes" of AI.

In this article, we explain this template keys´s: from its objectives and structure, to information on deadlines, penalties, and next steps.

Objectives and relevance of the template

General-purpose AI models are trained on data from a wide variety of sources and modalities, such as:

-

Text: books, scientific articles, press, social networks.

-

Images and videos: digital content from the Internet and visual collections.

-

Audio: recordings, podcasts, radio programs, or conversations.

-

User data: information generated in interaction with the model itself or with other services of the provider.

This process of mass data collection is often opaque, raising concerns among rights holders, users, regulators, and society as a whole. Without transparency, it is difficult to assess whether data has been obtained lawfully, whether it includes unauthorised personal information or whether it adequately represents the cultural and linguistic diversity of the European Union.

Recital 107 of the AI Act states that the main objective of this template is to increase transparency and facilitate the exercise and protection of rights. Among the benefits it provides, the following stand out:

-

Intellectual property protection: allows authors, publishers and other rights holders to identify if their works have been used during training, facilitating the defense of their rights and a fair use of their content.

-

Privacy safeguard: helps detect whether personal data has been used, providing useful information so that affected individuals can exercise their rights under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and other regulations in the same field.

-

Prevention of bias and discrimination: provides information on the linguistic and cultural diversity of the sources used, key to assessing and mitigating biases that may lead to discrimination.

-

Fostering competition and research: reduces "black box" effects and facilitates academic scrutiny, while helping other companies better understand where data comes from, favoring more open and competitive markets.

In short, this template is not only a legal requirement, but a tool to build trust in artificial intelligence, creating an ecosystem in which technological innovation and the protection of rights are mutually reinforcing.

Template structure

The template, officially published on 24 July 2025 after a public consultation with more than 430 participating organisations, has been designed so that the information is presented in a clear, homogeneous and understandable way, both for specialists and for the public.

It consists of three main sections, ranging from basic model identification to legal aspects related to data processing.

1. General information

It provides a global view of the provider, the model, and the general characteristics of the training data:

-

Identification of the supplier, such as name and contact details.

-

Identification of the model and its versions, including dependencies if it is a modification (fine-tuning) of another model.

-

Date of placing the model on the market in the EU.

-

Data modalities used (text, image, audio, video, or others).

-

Approximate size of data by modality, expressed in wide ranges (e.g., less than 1 billion tokens, between 1 billion and 10 trillion, more than 10 trillion).

-

Language coverage, with special attention to the official languages of the European Union.

This section provides a level of detail sufficient to understand the extent and nature of the training, without revealing trade secrets.

2. List of data sources

It is the core of the template, where the origin of the training data is detailed. It is organized into six main categories, plus a residual category (other).

-

Public datasets:

-

Data that is freely available and downloadable as a whole or in blocks (e.g., open data portals, common crawl, scholarly repositories).

-

"Large" sets must be identified, defined as those that represent more than 3% of the total public data used in a specific modality.

-

-

Licensed private sets:

-

Data obtained through commercial agreements with rights holders or their representatives, such as licenses with publishers for the use of digital books.

-

A general description is provided only.

-

-

Other unlicensed private data:

-

Databases acquired from third parties that do not directly manage copyright.

-

If they are publicly known, they must be listed; otherwise, a general description (data type, nature, languages) is sufficient.

-

-

Data obtained through web crawling/scraping:

-

Information collected by or on behalf of the supplier using automated tools.

-

It must be specified:

-

Name/identifier of the trackers.

-

Purpose and behavior (respect for robots.txt, captchas, paywalls, etc.).

-

Collection period.

-

Types of websites (media, social networks, blogs, public portals, etc.).

-

List of most relevant domains, covering at least the top 10% by volume. For SMBs, this requirement is adjusted to 5% or a maximum of 1,000 domains, whichever is less.

-

-

-

Users data:

-

Information generated through interaction with the model or with other provider services.

-

It must indicate which services contribute and the modality of the data (text, image, audio, etc.).

-

-

Synthetic data:

-

Data created by or for the supplier using other AI models (e.g., model distillation or reinforcement with human feedback - RLHF).

-

Where appropriate, the generator model should be identified if it is available in the market.

-

Additional category – Other: Includes data that does not fit into the above categories, such as offline sources, self-digitization, manual tagging, or human generation.

3. Aspects of data processing

It focuses on how data has been handled before and during training, with a particular focus on legal compliance:

-

Respect for Text and Data Mining (TDM): measures taken to honour the right of exclusion provided for in Article 4(3) of Directive 2019/790 on copyright, which allows rightholders to prevent the mining of texts and data. This right is exercised through opt-out protocols, such as tags in files or configurations in robots.txt, that indicate that certain content cannot be used to train models. Vendors should explain how they have identified and respected these opt-outs in their own datasets and in those purchased from third parties.

-

Removal of illegal content: procedures used to prevent or debug content that is illegal under EU law, such as child sexual abuse material, terrorist content or serious intellectual property infringements. These mechanisms may include blacklisting, automatic classifiers, or human review, but without revealing trade secrets.

The following diagram summarizes these three sections:

Balancing transparency and trade secrets

The European Commission has designed the template seeking a delicate balance: offering sufficient information to protect rights and promote transparency, without forcing the disclosure of information that could compromise the competitiveness of suppliers.

-

Public sources: the highest level of detail is required, including names and links to "large" datasets.

-

Private sources: a more limited level of detail is allowed, through general descriptions when the information is not public.

-

Web scraping: a summary list of domains is required, without the need to detail exact combinations.

-

User and synthetic data: the information is limited to confirming its use and describing the modality.

Thanks to this approach, the summary is "generally complete" in scope, but not "technically detailed", protecting both transparency and the intellectual and commercial property of companies.

Compliance, deadlines and penalties

Article 53 of the AI Act details the obligations of general-purpose model providers, most notably the publication of this summary of training data.

This obligation is complemented by other measures, such as:

-

Have a public copyright policy.

-

Implement risk assessment and mitigation processes, especially for models that may generate systemic risks.

-

Establish mechanisms for traceability and supervision of data and training processes.

Non-compliance can lead to significant fines, up to €15 million or 3% of the company's annual global turnover, whichever is higher.

Next Steps for Suppliers

To adapt to this new obligation, providers should:

-

Review internal data collection and management processes to ensure that necessary information is available and verifiable.

-

Establish clear transparency and copyright policies, including protocols to respect the right of exclusion in text and data mining (TDM).

-

Publish the abstract on official channels before the corresponding deadline.

-

Update the summary periodically, at least every six months or when there are material changes in training.

The European Commission, through the European AI Office, will monitor compliance and may request corrections or impose sanctions.

A key tool for governing data

In our previous article, "Governing Data to Govern Artificial Intelligence", we highlighted that reliable AI is only possible if there is a solid governance of data.

This new template reinforces that principle, offering a standardized mechanism for describing the lifecycle of data, from source to processing, and encouraging interoperability and responsible reuse.

This is a decisive step towards a more transparent, fair and aligned AI with European values, where the protection of rights and technological innovation can advance together.

Conclusions

The publication of the Public Summary Template marks a historic milestone in the regulation of AI in Europe. By requiring providers to document and make public the data used in training, the European Union is taking a decisive step towards a more transparent and trustworthy artificial intelligence, based on responsibility and respect for fundamental rights. In a world where data is the engine of innovation, this tool becomes the key to governing data before governing AI, ensuring that technological development is built on trust and ethics.

Content created by Dr. Fernando Gualo, Professor at UCLM and Government and Data Quality Consultant. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

When dealing with the liability arising from the use of autonomous systems based on the use of artificial intelligence , it is common to refer to the ethical dilemmas that a traffic accident can pose. This example is useful to illustrate the problem of liability for damages caused by an accident or even to determine other types of liability in the field of road safety (for example, fines for violations of traffic rules).

Let's imagine that the autonomous vehicle has been driving at a higher speed than the permitted speed or that it has simply skipped a signal and caused an accident involving other vehicles. From the point of view of the legal risks, the liability that would be generated and, specifically, the impact of data in this scenario, we could ask some questions that help us understand the practical scope of this problem:

-

Have all the necessary datasets of sufficient quality to deal with traffic risks in different environments (rural, urban, dense cities, etc.) been considered in the design and training?

-

What is the responsibility if the accident is due to poor integration of the artificial intelligence tool with the vehicle or a failure of the manufacturer that prevents the correct reading of the signs?

-

Who is responsible if the problem stems from incorrect or outdated information on traffic signs?

In this post we are going to explain what aspects must be considered when assessing the liability that can be generated in this type of case.

The impact of data from the perspective of the subjects involved

In the design, training, deployment and use of artificial intelligence systems, the effective control of the data used plays an essential role in the management of legal risks. The conditions of its processing can have important consequences from the perspective of liability in the event of damage or non-compliance with the applicable regulations.

A rigorous approach to this problem requires distinguishing according to each of the subjects involved in the process, from its initial development to its effective use in specific circumstances, since the conditions and consequences can be very different. In this sense, it is necessary to identify the origin of the damage or non-compliance in order to impute the legal consequences to the person who should effectively be considered responsible:

-

Thus, damage or non-compliance may be determined by a design problem in the application used or in its training, so that certain data is misused for this purpose. Continuing with the example of an autonomous vehicle, this would be the case of accessing the data of the people traveling in it without consent.

-

However, it is also possible that the problem originates from the person who deploys the tool in each environment for real use, a position that would be occupied by the vehicle manufacturer. This could happen if, for its operation, data is accessed without the appropriate permissions or if there are restrictions that prevent access to the information necessary to guarantee its proper functioning.

-

The problem could also be generated by the person or entity using the tool itself. Returning to the example of the vehicle, it could be stated that the ownership of the vehicle corresponds to a company or an individual that has not carried out the necessary periodic inspections or updated the system when necessary.

-

Finally, there is the possibility that the legal problem of liability is determined by the conditions under which the data are provided at their original source. For example, if the data is inaccurate: the information about the road on which the vehicle is traveling is not up to date or the data emitted by traffic signs is not sufficiently accurate.

Challenges related to the technological environment: complexity and opacity

In addition, the very uniqueness of the technology used may significantly condition the attribution of liability. Specifically, technological opacity – that is, the difficulty in understanding why a system makes a specific decision – is one of the main challenges when it comes to addressing the legal challenges posed by artificial intelligence, as it makes it difficult to determine the responsible subject. This is a problem that acquires special importance with regard to the lawful origin of the data and, likewise, the conditions under which its processing takes place. In fact, this was precisely the main stumbling block that generative artificial intelligence encountered in the initial moments of its landing in Europe: the lack of adequate conditions of transparency regarding the processing of personal data justified the temporary halt of its commercialization until the necessary adjustments were made.

In this sense, the publication of the data used for the training phase becomes an additional guarantee from the perspective of legal certainty and, specifically, to verify the regulatory compliance conditions of the tool.

On the other hand, the complexity inherent in this technology poses an additional difficulty in terms of the imputation of the damage that may be caused and, consequently, in the determination of who should pay for it. Continuing with the example of the autonomous vehicle, it could be the case that various causes overlap, such as the inaccuracy of the data provided by traffic signs and, at the same time, a malfunction of the computer application by not detecting potential inconsistencies between the data used and its actual needs.

What does the regulation of the European Regulation on artificial intelligence say about it?

Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 establishes a harmonised regulatory framework across the European Union in relation to artificial intelligence. With regard to data, it includes some specific obligations for systems classified as "high risk", which are those contemplated in Article 6 and in the list in Annex III (biometric identification, education, labour management, access to essential services, etc.). In this sense, it incorporates a strict regime of technical requirements, transparency, supervision and auditing, combined with conformity assessment procedures prior to its commercialization and post-market control mechanisms, also establishing precise responsibilities for suppliers, operators and other actors in the value chain.

As regards data governance, a risk management system should be put in place covering the entire lifecycle of the tool and assessing, mitigating, monitoring and documenting risks to health, safety and fundamental rights. Specifically, training, validation, and testing datasets are required to be:

-

Relevant, representative, complete and as error-free as possible for the intended purpose.

-

Managed in accordance with strict governance practices that mitigate bias and discrimination, especially when they may affect the fundamental rights of vulnerable or minority groups.

-

The Regulation also lays down strict conditions for the exceptional use of special categories of personal data with regard to the detection and, where appropriate, correction of bias.

With regard to technical documentation and record keeping, the following are required:

-

The preparation and maintenance of exhaustive technical documentation. In particular, with regard to transparency, complete and clear instructions for use should be provided, including information on data and output results, among other things.

-

Systems should allow for the automatic recording of relevant events (logs) throughout their life cycle to ensure traceability and facilitate post-market surveillance, which can be very useful when checking the incidence of the data used.

As regards liability, that regulation is based on an approach that is admittedly limited from two points of view:

-

Firstly, it merely empowers Member States to establish a sanctioning regime that provides for the imposition of fines and other means of enforcement, such as warnings and non-pecuniary measures, which must be effective, proportionate and dissuasive of non-compliance with the regulation. They are, therefore, instruments of an administrative nature and punitive in nature, that is, punishment for non-compliance with the obligations established in said regulation, among which are those relating to data governance and the documentation and conservation of records referred to above.

-

However, secondly, the European regulator has not considered it appropriate to establish specific provisions regarding civil liability with the aim of compensating for the damage caused. This is an issue of great relevance that even led the European Commission to formulate a proposal for a specific Directive in 2022. Although its processing has not been completed, it has given rise to an interesting debate whose main arguments have been systematised in a comprehensive report by the European Parliament analysing the impact that this regulation could have.

No clear answers: open debate and regulatory developments

Thus, despite the progress made by the approval of the 2024 Regulation, the truth is that the regulation of liability arising from the use of artificial intelligence tools remains an open question on which there is no complete and developed regulatory framework. However, once the approach regarding the legal personification of robots that arose a few years ago has been overcome, it is unquestionable that artificial intelligence in itself cannot be considered a legally responsible subject.

As emphasized above, this is a complex debate in which it is not possible to offer simple and general answers, since it is essential to specify them in each specific case, taking into account the subjects that have intervened in each of the phases of design, implementation and use of the corresponding tool. It will therefore be these subjects who will have to assume the corresponding responsibility, either for the compensation of the damage caused or, where appropriate, to face the sanctions and other administrative measures in the event of non-compliance with the regulation.

In short, although the European regulation on artificial intelligence of 2024 may be useful to establish standards that help determine when a damage caused is contrary to law and, therefore, must be compensated, the truth is that it is an unclosed debate that will have to be redirected applying the general rules on consumer protection or defective products, taking into account the singularities of this technology. And, as far as administrative responsibility is concerned, it will be necessary to wait for the initiative that was announced a few months ago and that is pending formal approval by the Council of Ministers for its subsequent parliamentary processing in the Spanish Parliament.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The idea of conceiving artificial intelligence (AI) as a service for immediate consumption or utility, under the premise that it is enough to "buy an application and start using it", is gaining more and more ground. However, getting on board with AI isn't like buying conventional software and getting it up and running instantly. Unlike other information technologies, AI will hardly be able to be used with the philosophy of plug and play. There is a set of essential tasks that users of these systems should undertake, not only for security and legal compliance reasons, but above all to obtain efficient and reliable results.

The Artificial Intelligence Regulation (RIA)[1]

The RIA defines frameworks that should be taken into account by providers[2] and those responsible for deploying[3] AI. This is a very complex rule whose orientation is twofold. Firstly, in an approach that we could define as high-level, the regulation establishes a set of red lines that can never be crossed. The European Union approaches AI from a human-centred and human-serving approach. Therefore, any development must first and foremost ensure that fundamental rights are not violated or that no harm is caused to the safety and integrity of people. In addition, no AI that could generate systemic risks to democracy and the rule of law will be admitted. For these objectives to materialize, the RIA deploys a set of processes through a product-oriented approach. This makes it possible to classify AI systems according to their level of risk, -low, medium, high- as well as general-purpose AI models[4]. And also, to establish, based on this categorization, the obligations that each participating subject must comply with to guarantee the objectives of the standard.

Given the extraordinary complexity of the European regulation, we would like to share in this article some common principles that can be deduced from reading it and could inspire good practices on the part of public and private organisations. Our approach is not so much on defining a roadmap for a given information system as on highlighting some elements that we believe can be useful in ensuring that the deployment and use of this technology are safe and efficient, regardless of the level of risk of each AI-based information system.

Define a clear purpose

The deployment of an AI system is highly dependent on the purpose pursued by the organization. It is not about jumping on the bandwagon of a fashion. It is true that the available public information seems to show that the integration of this type of technology is an important part of the digital transformation processes of companies and the Administration, providing greater efficiency and capabilities. However, it cannot become a fad to install any of the Large Language Models (LLMs). Prior reflection is needed that takes into account what the needs of the organization are and defines what type of AI will contribute to the improvement of our capabilities. Not adopting this strategy could put our bank at risk, not only from the point of view of its operation and results, but also from a legal perspective. For example, introducing an LLM or chatbot into a high-decision-making risk environment could result in reputational impacts or liability. Inserting this LLM in a medical environment, or using a chatbot in a sensitive context with an unprepared population or in critical care processes, could end up generating risk situations with unforeseeable consequences for people.

Do no evil

The principle of non-malefficiency is a key element and should decisively inspire our practice in the world of AI. For this reason, the RIA establishes a series of practices expressly prohibited to protect the fundamental rights and security of people. These prohibitions focus on preventing manipulations, discrimination, and misuse of AI systems that can cause significant harm.

Categories of Prohibited Practices

1. Manipulation and control of behavior. Through the use of subliminal or manipulative techniques that alter the behavior of individuals or groups, preventing informed decision-making and causing considerable damage.

2. Exploiting vulnerabilities. Derived from age, disability or social/economic situation to substantially modify behavior and cause harm.

3. Social Scoring. AI that evaluates people based on their social behavior or personal characteristics, generating ratings with effects for citizens that result in unjustified or disproportionate treatment.

4. Criminal risk assessment based on profiles. AI used to predict the likelihood of committing crimes solely through profiling or personal characteristics. Although its use for criminal investigation is admitted when the crime has actually been committed and there are facts to be analyzed.

5. Facial recognition and biometric databases. Systems for the expansion of facial recognition databases through the non-selective extraction of facial images from the Internet or closed circuit television.

6. Inference of emotions in sensitive environments. Designing or using AI to infer emotions at work or in schools, except for medical or safety reasons.

7. Sensitive biometric categorization. Develop or use AI that classifies individuals based on biometric data to infer race, political opinions, religion, sexual orientation, etc.

8. Remote biometric identification in public spaces. Use of "real-time" remote biometric identification systems in public spaces for police purposes, with very limited exceptions (search for victims, prevention of serious threats, location of suspects of serious crimes).

Apart from the expressly prohibited conduct, it is important to bear in mind that the principle of non-maleficence implies that we cannot use an AI system with the clear intention of causing harm, with the awareness that this could happen or, in any case, when the purpose we pursue is contrary to law.

Ensure proper data governance

The concept of data governance is found in Article 10 of the RIA and applies to high-risk systems. However, it contains a set of principles that are highly cost-effective when deploying a system at any level. High-risk AI systems that use data must be developed with training, validation, and testing suites that meet quality criteria. To this end, certain governance practices are defined to ensure:

- Proper design.

- That the collection and origin of the data, and in the case of personal data the purpose pursued, are adequate and legitimate.

- Preparation processes such as annotation, labeling, debugging, updating, enrichment, and aggregation are adopted.

- That the system is designed with use cases whose information is consistent with what the data is supposed to measure and represent.

- Ensure data quality by ensuring the availability, quantity, and adequacy of the necessary datasets.

- Detect and review biases that may affect the health and safety of people, rights or generate discrimination, especially when data outputs influence the input information of future operations. Measures should be taken to prevent and correct these biases.

- Identify and resolve gaps or deficiencies in data that impede RIA compliance, and we would add legislation.

- The datasets used should be relevant, representative, complete and with statistical properties appropriate for their intended use and should consider the geographical, contextual or functional characteristics necessary for the system, as well as ensure its diversity. In addition, they shall be error-free and complete in view of their intended purpose.

AI is a technology that is highly dependent on the data that powers it. From this point of view, not having data governance can not only affect the operation of these tools, but could also generate liability for the user.

In the not too distant future, the obligation for high-risk systems to obtain a CE marking issued by a notified body (i.e., designated by a member state of the European Union) will provide conditions of reliability to the market. However, for the rest of the lower-risk systems, the obligation of transparency applies. This does not at all imply that the design of this AI should not take these principles into account as far as possible. Therefore, before making a contract, it would be reasonable to verify the available pre-contractual information both in relation to the characteristics of the system and its reliability and with respect to the conditions and recommendations for deployment and use.

Another issue concerns our own organization. If we do not have the appropriate regulatory, organizational, technical and quality compliance measures that ensure the reliability of our own data, we will hardly be able to use AI tools that feed on it. In the context of the RIA, the user of a system may also incur liability. It is perfectly possible that a product of this nature has been properly developed by the supplier and that in terms of reproducibility the supplier can guarantee that under the right conditions the system works properly. What developers and vendors cannot solve are the inconsistencies in the datasets that the user-client integrates into the platform. It is not your responsibility if the customer failed to properly deploy a General Data Protection Regulation compliance framework or is using the system for an unlawful purpose. Nor will it be their responsibility for the client to maintain outdated or unreliable data sets that, when introduced into the tool, generate risks or contribute to inappropriate or discriminatory decision-making.

Consequently, the recommendation is clear: before implementing an AI-based system, we must ensure that data governance and compliance with current legislation are adequately guaranteed.

Ensuring Safety

AI is a particularly sensitive technology that presents specific security risks, such as the corruption of data sets. There is no need to look for fancy examples. Like any information system, AI requires organizations to deploy and use them securely. Consequently, the deployment of AI in any environment requires the prior development of a risk analysis that allows identifying which are the organizational and technical measures that guarantee a safe use of the tool.

Train your staff

Unlike the GDPR, in which this issue is implicit, the RIA expressly establishes the duty to train as an obligation. Article 4 of the RIA is so precise that it is worthwhile to reproduce it in its entirety:

Providers and those responsible for deploying AI systems shall take measures to ensure that, to the greatest extent possible, their staff and others responsible on their behalf for the operation and use of AI systems have a sufficient level of AI literacy, taking into account their technical knowledge; their experience, education and training, as well as the intended context of use of AI systems and the individuals or groups of people in whom those systems are to be used.