The Data Governance Act (DGA) is part of a complex web of EU public policy and regulation, the ultimate goal of which is to create a dataset ecosystem that feeds the digital transformation of the Member States and the objectives of the European Digital Decade:

- A digitally empowered population and highly skilled digital professionals.

- Secure and sustainable digital infrastructures.

- Digital transformation of companies.

- Digitisation of public services.

Public opinion is focusing on artificial intelligence from the point of view of both the opportunities and, above all, the risks and uncertainties. However, the challenge is much more profound as it involves in each of the different layers very diverse technologies, products and services whose common element lies in the need to favour the availability of a high volume of reliable and quality-checked data to support their development.

Promoting the use of data with legislation as leverage

At its inception the Directive 2019/1024 on open data and re-use of public sector information (Open Data Directive), the Directive 95/46/EC on the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and subsequently the Regulation 2016/679 known as the General Data Protection Regulation(GDPR) opted for the re-use of data with full guarantee of rights. However, its interpretation and application generated in practice an effect contrary to its original objectives, clearly swinging towards a restrictive model that may have affected the processes of data generation for its exploitation. The large US platforms, through a strategy of free services - search engines, mobile applications and social networks - in exchange for personal data and with mere consent, obtained the largest volume of personal data in human history, including images, voice and personality profiles.

With the GDPR, the EU wanted to eliminate 28 different ways of applying prohibitions and limitations to the use of data. Regulatory quality certainly improved, although perhaps the results achieved have not been as satisfactory as expected and this is indicated by documents such as the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2022 or the Draghi Report (The future of European competitiveness-Part A. A competitiveness strategy for Europe).

This has forced a process of legislative re-engineering that expressly and homogeneously defines the rules that make the objectives possible. The reform of the Open Data Directive, the DGA, the Artificial Intelligence Regulation and the future European Health Data Space (EHDS) should be read from at least two perspectives:

- The first of these is at a high level and its function is aimed at preserving our constitutional values. The regulation adopts an approach focused on risk and on guaranteeing the dignity and rights of individuals, seeking to avoid systemic risks to democracy and fundamental rights.

- The second is operational, focusing on safe and responsible product development. This strategy is based on the definition of process engineering rules for the design of products and services that make European products a global benchmark for robustness, safety and reliability.

A Practical Guide to the Data Governance Law

Data protection by design and by default, the analysis of risks to fundamental rights, the development process of high-risk artificial intelligence information systems validated by the corresponding bodies or the processes of access and reuse of health data are examples of the legal and technological engineering processes that will govern our digital development. These are not easy procedures to implement. The European Union is therefore making a significant effort to fund projects such as TEHDAS, EUHubs4Data or Quantum , which operate as a testing ground. In parallel, studies are carried out or guides are published, such as the Practical Guide to the Data Governance Law.

This Guide recalls the essential objectives of the DGA:

- Regulate the re-use of certain publicly owned data subject to the rights of third parties ("protected data", such as personal data or commercially confidential or proprietary data).

- Boost data sharing by regulating data brokering service providers.

- Encourage the exchange of data for altruistic purposes.

- Establish the European Data Innovation Board to facilitate the exchange of best practices.

The DGA promotes the secure re-use of data through various measures and safeguards. These focus on the re-use of data from public sector bodies, data brokering services and data sharing for altruistic purposes.

To which data does it apply? Legitimation for the processing of protected data held by public sector bodies

In the public sector they are protected:

- Confidential business data, such as trade secrets or know-how.

- Statistically confidential data.

- Data protected by the intellectual property rights of third parties.

- Personal data, insofar as such data do not fall within the scope of the Open Data Directive when irreversible anonymisation is ensured and no special categories of data are concerned.

An essential starting point should be underlined: as far as personal data are concerned, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the rules on privacy and electronic communications (Directive 2002/58/EC) also apply. This implies that, in the event of a collision between them and the DGA, the former will prevail.

Moreover, the DGA does not create a right of re-use or a new legal basis within the meaning of the GDPR for the re-use of personal data. This means that Member State or Union law determines whether a specific database or register containing protected data is open for re-use in general. Where such re-use is permitted, it must be carried out in accordance with the conditions laid down in Chapter I of the DGA.

Finally, they are excluded from the scope of the DGA:

- Data held by public companies, museums, schools and universities.

- Data protected for reasons of public security, defence or national security.

- Data held by public sector bodies for purposes other than the performance of their defined public functions.

- Exchange of data between researchers for non-commercial scientific research purposes.

Conditions for re-use of data

It can be noted that in the area of re-use of public sector data:

▪ The DGA establishes rules for the re-use of protected data, such as personal data, confidential commercial data or statistically sensitive data.

▪ It does not create a general right of re-use, but establishes conditions where national or EU law allows such re-use.

▪ The conditions for access must be transparent, proportionate and objective, and must not be used to restrict competition. The rule mandates the promotion of data access for SMEs and start-ups, and scientific research. Exclusivity agreements for re-use are prohibited, except in specific cases of public interest and for a limited period of time.

▪ Attributes to public sector bodies the duty to ensure the preservation of the protected nature of the data. This will require the deployment of intermediation methodologies and technologies. Anonymisation and access through secure processing environments (Secure processing environments or SPE) can play a key role. The former is a risk elimination factor, while PES can define a processing ecosystem that provides a comprehensive service offering to re-users, from the cataloguing and preparation of datasets to their analysis. The Spanish Data Protection Agency has published an Approach to data spaces from a GDPR perspective that includes recommendations and methodologies in this area.

▪ Re-users are subject to obligations of confidentiality and non-identification of data subjects. In case of re-identification of personal data, the re-user must inform the public sector body and there may be security breach notification obligations.

▪ Insofar as the relationship is established directly between the re-user and the public sector body, there may be cases in which the latter must provide support to the former for the fulfilment of certain duties:

- To obtain, if necessary, the consent of the persons concerned for the processing of personal data.

- In case of unauthorised use of non-personal data, the re-user shall inform the legal entities concerned. The public sector body that initially granted the permission for re-use may provide support if necessary.

▪ International transfers of personal data are governed by the GDPR. For international transfers of non-personal data, the re-user is required to inform the public sector body and to contractually commit to ensure data protection. However, this is an open question, since, as with the GDPR, the European Commission has the power to:

1. Propose standard contractual clauses that public sector bodies can use in their transfer contracts with re-users.

2. Where a large number of requests for re-use from specific countries justify it, adopt "equivalence decisions" designating these third countries as providing a level of protection for trade secrets or intellectual property that can be considered equivalent to that provided for in the EU.

3. Adopt the conditions to be applied to transfers of highly sensitive non-personal data, such as health data. In cases where the transfer of such data to third countries poses a risk to EU public policy objectives (in this example, public health) and in order to assist public sector bodies granting permissions for re-use, the Commission will set additional conditions to be met before such data can be transferred to a third country.

▪ Public sector bodies may charge fees for allowing re-use. The DGA's strategy aims at sustainability of the system, as fees should only cover the costs of making data available for re-use, such as the costs of anonymisation or providing a secure processing environment. This would include the costs of processing requests for re-use. Member States must publish a description of the main cost categories and the rules used for their allocation.

▪ Natural or legal persons directly affected by a decision on re-use taken by a public sector body shall have the right to lodge a complaint or to seek a judicial remedy in the Member State of that public sector body.

Organisational support

It is entirely possible that public sector bodies offering intermediation services will multiply. This is a complex environment that will require technical and legal support, backstopping and coordination.

To this end, Member States should designate one or more competent bodies whose role is to support public sector bodies granting re-use. The competent bodies shall have adequate legal, financial, technical and human resources to carry out the tasks assigned to them, including the necessary expertise. They are not supervisory bodies, they do not exercise public powers and, as such, the DGA does not set specific requirements as to their status or legal form. In addition, the competent body may be given a mandate to allow re-use itself.

Finally, States must create a Single Point of Information or one-stop shop. This Point will be responsible for transmitting queries and requests to relevant public sector bodies and for maintaining an asset list with an overview of available data resources (metadata). The single information point may be linked to local, regional or sectoral information points where they exist. At EU level, the Commission created the European Register of Protected Data held by the Public Sector (ERPD), a searchable register of information collected by national single points of information to further facilitate the re-use of data in the internal market and beyond.

EU regulations are rules that are complex to implement. Therefore, a special pro-activity is required to contribute to its correct understanding and implementation. The EU Guide to the Deployment of the Data Governance Act is a first tool for this purpose and will allow a better understanding of the objectives and possibilities offered by the DGA.

Content prepared by Ricard Martínez Martínez, Director of the Chair in Privacy and Digital Transformation, Department of Constitutional Law of the Universitat de València. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

In this episode we will discuss artificial intelligence and its challenges, based on the European Regulation on Artificial Intelligence that entered into force this year. Come and find out about the challenges, opportunities and new developments in the sector from two experts in the field:

- Ricard Martínez, professor of constitutional law at the Universitat de València where he directs the Chair of Privacy and Digital Transformation Microsoft University of Valencia.

- Carmen Torrijos, computational linguist, expert in AI applied to language and professor of text mining at the Carlos III University.

Listen to the full podcast (only available in Spanish)

Summary of the interview

1. It is a fact that artificial intelligence is constantly evolving. To get into the subject, I would like to hear about the latest developments in AI?

Carmen Torrijos: Many new applications are emerging. For example, this past weekend there has been a lot of buzz about an AI for image generation in X (Twitter), I don't know if you've been following it, called Grok. It has had quite an impact, not because it brings anything new, as image generation is something we have been doing since December 2023. But this is an AI that has less censorship, that is, until now we had a lot of difficulties with the generalist systems to make images that had faces of celebrities or had certain situations and it was very monitored from any tool. What Grok does is to lift all that up so that anyone can make any kind of image with any famous person or any well-known face. It is probably a passing fad. We will make images for a while and then it will pass.

And then there are also automatic podcast creation systems, such as Notebook LM. We've been watching them for a couple of months now and it's really been one of the things that has really surprised me in the last few months. Because it already seems that they are all incremental innovations: on top of what we already have, they give us something better. But this is something really new and surprising. You upload a PDF and it can generate a podcast of two people talking in a totally natural, totally realistic way about that PDF. This is something that Notebook LM, which is owned by Google, can do.

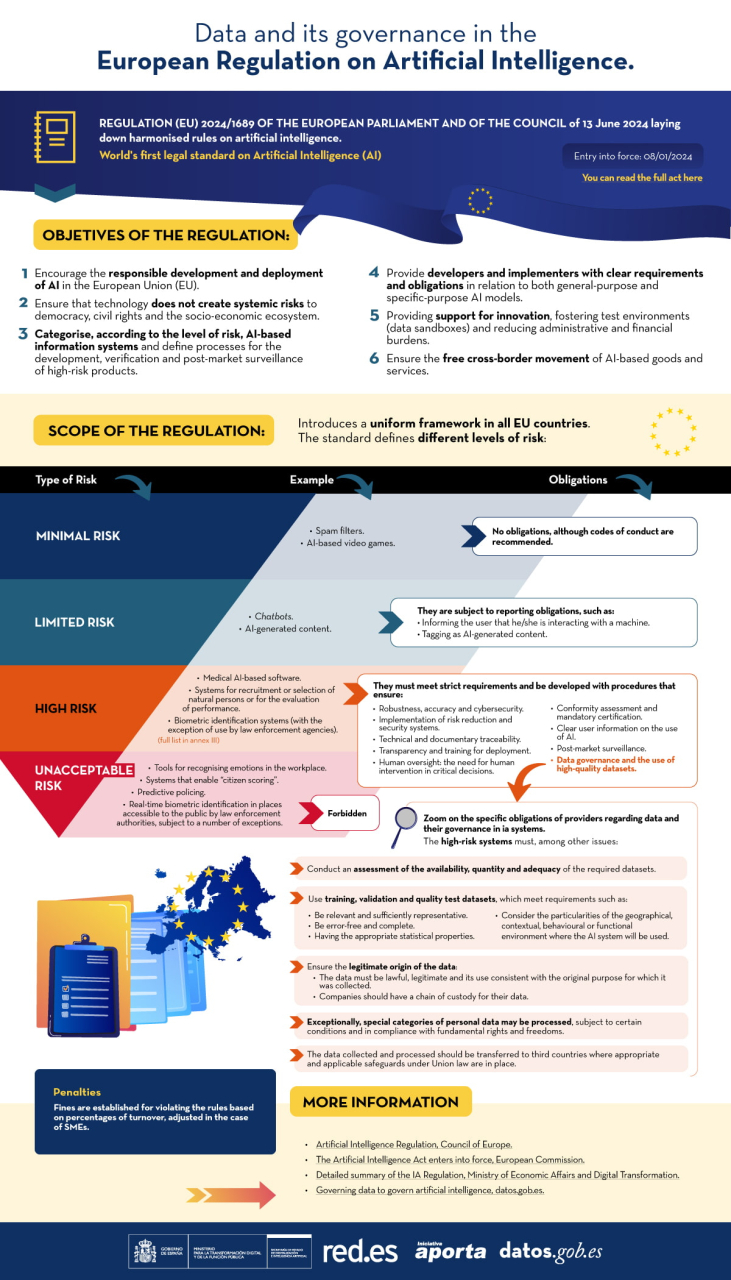

2. The European Regulation on Artificial Intelligence is the world's first legal regulation on AI, with what objectives is this document, which is already a reference framework at international level, being published?

Ricard Martínez: The regulation arises from something that is implicit in what Carmen has told us. All this that Carmen tells is because we have opened ourselves up to the same unbridled race that we experienced with the emergence of social media. Because when this happens, it's not innocent, it's not that companies are being generous, it's that companies are competing for our data. They gamify us, they encourage us to play, they encourage us to provide them with information, so they open up. They do not open up because they are generous, they do not open up because they want to work for the common good or for humanity. They open up because we are doing their work for them. What does the EU want to stop? What we learned from social media. The European Union has two main approaches, which I will try to explain very succinctly. The first approach is a systemic risk approach. The European Union has said: "I will not tolerate artificial intelligence tools that may endanger the democratic system, i.e. the rule of law and the way I operate, or that may seriously infringe fundamental rights". That is a red line.

The second approach is a product-oriented approach. An AI is a product. When you make a car, you follow rules that manage how you produce that car, and that car comes to market when it is safe, when it has all the specifications. This is the second major focus of the Regulation. The regulation says that you can be developing a technology because you are doing research and I almost let you do whatever you want. Now, if this technology is to come to market, you will catalogue the risk. If the risk is low or slight, you are going to be able to do a lot of things and, practically speaking, with transparency and codes of conduct, I will give you a pass. But if it's a high risk, you're going to have to follow a standardised design process, and you're going to need a notified body to verify that technology, make sure that in your documentation you've met what you have to meet, and then they'll give you a CE mark. And that's not the end of it, because there will be post-trade surveillance. So, throughout the life cycle of the product, you need to ensure that this works well and that it conforms to the standard.

On the other hand, a tight control is established with regard to big data models, not only LLM, but also image or other types of information, where it is believed that they may pose systemic risks.

In that case, there is a very direct control by the Commission. So, in essence, what they are saying is: "respect rights, guarantee democracy, produce technology in an orderly manner according to certain specifications".

Carmen Torrijos: Yes, in terms of objectives it is clear. I have taken up Ricard's last point about producing technology in accordance with this Regulation. We have this mantra that the US does things, Europe regulates things and China copies things. I don't like to generalise like that. But it is true that Europe is a pioneer in terms of legislation and we would be much stronger if we could produce technology in line with the regulatory standards we are setting. Today we still can't, maybe it's a question of giving ourselves time, but I think that is the key to technological sovereignty in Europe.

3. In order to produce such technology, AI systems need data to train their models. What criteria should the data meet in order to train an AI system correctly? Could open data sets be a source? In what way?

Carmen Torrijos: The data we feed AI with is the point of greatest conflict. Can we train with any dataset even if it is available? We are not talking about open data, but about available data.

Open data is, for example, the basis of all language models, and everyone knows this, which is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is an ideal example for training, because it is open, it is optimised for computational use, it is downloadable, it is very easy to use, there is a lot of language, for example, for training language models, and there is a lot of knowledge of the world. This makes it the ideal dataset for training an AI model. And Wikipedia is in the open, it is available, it belongs to everyone and it is for everyone, you can use it.

But can all the datasets available on the Internet be used to train AI systems? That is a bit of a doubt. Because the fact that something is published on the Internet does not mean that it is public, for public use, although you can take it and train a system and start generating profit from that system. It had a copyright, authorship and intellectual property. That I think is the most serious conflict we have right now in generative AI because it uses content to inspire and create. And there, little by little, Europe is taking small steps. For example, the Ministry of Culture has launched an initiative to start looking at how we can create content, licensed datasets, to train AI in a way that is legal, ethical and respectful of authors' intellectual property rights.

All this is generating a lot of friction. Because if we go on like this, we will turn against many illustrators, translators, writers, etc. (all creators who work with content), because they will not want this technology to be developed at the expense of their content. Somehow you have to find a balance in regulation and innovation to make both happen. From the large technological systems that are being developed, especially in the United States, there is a repeated idea that only with licensed content, with legal datasets that are free of intellectual property, or that the necessary returns have been paid for their intellectual property, it is not possible to reach the level of quality of AIs that we have now. That is, only with legal datasets alone we would not have ChatGPT at the level ChatGPT is at now.

This is not set in stone and does not have to be the case. We have to continue researching, that is, we have to continue to see how we can achieve a technology of that level, but one that complies with the regulation. Because what they have done in the United States, what GPT-4 has done, the great models of language, the great models of image generation, is to show us the way. This is as far as we can go. But you have done so by taking content that is not yours, that it was not permissible to take. We have to get back to that level of quality, back to that level of performance of the models, respecting the intellectual property of the content. And that is a role that I believe is primarily Europe's responsibility.

4. Another issue of public concern with regard to the rapid development of AI is the processing of personal data. How should they be protected and what conditions does the European regulation set for this?

Ricard Martínez: There is a set of conducts that have been prohibited essentially to guarantee the fundamental rights of individuals. But it is not the only measure. I attach a great deal of importance to an article in the regulation that we are probably not going to give much thought to, but for me it is key. There is an article, the fourth one, entitled AI Literacy, which says that any subject that is intervening in the value chain must have been adequately trained. You have to know what this is about, you have to know what the state of the art is, you have to know what the implications are of the technology you are going to develop or deploy. I attach great value to it because it means incorporating throughout the value chain (developer, marketer, importer, company deploying a model for use, etc.) a set of values that entail what is called accountability, proactive responsibility, by default. This can be translated into a very simple element, which has been talked about for two thousand years in the world of law, which is 'do no harm', the principle of non-maleficence.

With something as simple as that, "do no harm to others, act in good faith and guarantee your rights", there should be no perverse effects or harmful effects, which does not mean that it cannot happen. And this is precisely what the Regulation says in particular when it refers to high-risk systems, but it is applicable to all systems. The Regulation tells you that you have to ensure compliance processes and safeguards throughout the life cycle of the system. That is why it is so important to have robustness, resilience and contingency plans that allow you to revert, shut down, switch to human control, change the usage model when an incident occurs.

Therefore, the whole ecosystem is geared towards this objective of no harm, no rights, no harm. And there is an element that no longer depends on us, it depends on public policy. AI will not only infringe on rights, it will change the way we understand the world. If there are no public policies in the education sector that ensure that our children develop computational thinking skills and are able to have a relationship with a machine-interface, their access to the labour market will be significantly affected. Similarly, if we do not ensure the continuous training of active workers and also the public policies of those sectors that are doomed to disappear.

Carmen Torrijos: I find Ricard's approach of to train is to protect very interesting. Train people, inform people, get people trained in AI, not only people in the value chain, but everybody. The more you train and empower, the more you are protecting people.

When the law came out, there was some disappointment in AI environments and especially in creative environments. Because we were in the midst of the generative AI boom and generative AI was hardly being regulated, but other things were being regulated that we took for granted would not happen in Europe, but that have to be regulated so that they cannot happen. For example, biometric surveillance: Amazon can't read your face to decide whether you are sadder that day and sell you more stuff or get more advertising or a particular advertisement. I say Amazon, but it can be any platform. This, for example, will not be possible in Europe because it is forbidden by law, it is an unacceptable use: biometric surveillance.

Another example is social scoring, the social scoring that we see happening in China, where citizens are given points and access to public services based on these points. That is not going to be possible either. And this part of the law must also be considered, because we take it for granted that this is not going to happen to us, but when you don't regulate it, that's when it happens. China has installed 600 million TRF cameras, facial recognition technology, which recognise you with your ID card. That is not going to happen in Europe because it cannot, because it is also biometric surveillance. So you have to understand that the law perhaps seems to be slowing down on what we are now enraptured by, which is generative AI, but it has been dedicated to addressing very important points that needed to be covered in order to protect people. In order not to lose fundamental rights that we have already won.

Finally, ethics has a very uncomfortable component, which nobody wants to look at, which is that sometimes it has to be revoked. Sometimes it is necessary to remove something that is in operation, even that is providing a benefit, because it is incurring some kind of discrimination, or because it is bringing some kind of negative consequence that violates the rights of a collective, of a minority or of someone vulnerable. And that is very complicated. When we have become accustomed to having an AI operating in a certain context, which may even be a public context, to stop and say that this is discriminating against people, then this system cannot continue in production and has to be removed. This point is very complicated, it is very uncomfortable and when we talk about ethics, which we talk very easily about ethics, we must also think about how many systems we are going to have to stop and review before we can put them back into operation, however easy they make our lives or however innovative they may seem.

5. In this sense, taking into account all that the Regulation contains, some Spanish companies, for example, will have to adapt to this new framework. What should organisations already be doing to prepare? What should Spanish companies review in the light of the European regulation?

Ricard Martínez: This is very important, because there is a corporate business level of high capabilities that I am not worried about because these companies understand that we are talking about an investment. And just as they invested in a process-based model that integrated the compliance from the design for data protection. The next leap, which is to do exactly the same thing with artificial intelligence, I won't say that it is unimportant, because it is of relevant importance, but let's say that it is going down a path that has already been tried. These companies already have compliance units, they already have advisors, and they already have routines into which the artificial intelligence regulatory framework can be integrated as part of the process. In the end, what it will do is to increase risk analysis in one sense. It will surely force the design processes and also the design phases themselves to be modular, i.e., while in software design we are practically talking about going from a non-functional model to chopping up code, here there are a series of tasks of enrichment, annotation, validation of the data sets, prototyping that surely require more effort, but they are routines that can be standardised.

My experience in European projects where we have worked with clients, i.e. SMEs, who expect AI to be plug and play, what we have seen is a huge lack of capacity building. The first question you should ask yourself is not whether your company needs AI, but whether your company is ready for AI. This is an earlier and rather more relevant question. Hey, you think you can make a leap into AI, that you can contract a certain type of services, and we are realising that you don't even comply with the data protection regulation.

There is something, an entity called the Spanish Agency for Artificial Intelligence, AESIA, and there is a Ministry of Digital Transformation, and if there are no accompanying public policies, we may incur risky situations. Why? Because I have the great pleasure of training future entrepreneurs in artificial intelligence in undergraduate and postgraduate courses. When confronted with the ethical and legal framework, I won't say they want to die, but the world comes crashing down on them. Because there is no support, there is no accompaniment, there are no resources, or they cannot see them, that do not involve a round of investment that they cannot bear, or there are no guided models that help them in a way that is, I won't say easy, but at least usable.

Therefore, I believe that there is a substantial challenge in public policies, because if this combination does not happen, the only companies that will be able to compete are those that already have a critical mass, an investment capacity and an accumulated capital that allows them to comply with the standard. This situation could lead to a counterproductive outcome.

We want to regain European digital sovereignty, but if there are no public investment policies, the only ones who will be able to comply with the European standard are companies from other countries.

Carmen Torrijos: Not because they are from other countries but because they are bigger.

Ricard Martínez: Yes, not to mention countries.

6. We have talked about challenges, but it is also important to highlight opportunities. What positive aspects could you highlight as a result of this recent regulation?

Ricard Martínez: I am working on the construction, with European funding, of Cancer Image EU , which is intended to be a digital infrastructure for cancer imaging. At the moment, we are talking about a partnership involving 14 countries, 76 organisations, on the way to 93, to generate a medical imaging database of 25 million cancer images with associated clinical information for the development of artificial intelligence. The infrastructure is being built, it does not yet exist, and even so, at the Hospital La Fe in Valencia, research is already underway with mammograms of women who have undergone biennial screening and then developed cancer, to see if it is capable of training an image analysis model that is capable of preventively recognising that little spot that the oncologist or radiologist did not see and that later turned out to be a cancer. Does it mean you're getting chemotherapy five minutes later? No. It means they are going to monitor you, they are going to have an early reaction capability. And that the health system will save 200,000 euros. To mention just one opportunity.

On the other hand, opportunities must also be sought in other rules. Not only in the Artificial Intelligence Regulation. You have to go to Data Governance Act. It wants to counter the data monopoly held by US companies with a sharing of data from the public, private sectorand from the citizenry itself. With Data Act, which aims to empower citizens to retrieve their data and share it by consent. And finally with the European Health Data Space which aims to create ahealth data ecosystem to promote innovation, research and entrepreneurship. It is this ecosystem of data spaces that should be a huge generator of opportunity spaces.

And furthermore, I don't know whether they will succeed or not, but it aims to be coherent with our business ecosystem. That is to say, an ecosystem of small and medium-sized enterprises that does not have high data generation capabilities and what we are going to do is to build the field for them. We are going to create the data spaces for them, we are going to create the intermediaries, the intermediation services, and we hope that this ecosystem as a whole will allow European talent to emerge from small and medium-sized enterprises. Will it be achieved or not? I don't know, but the opportunity scenario looks very interesting.

Carmen Torrijos: If you ask for opportunities, all opportunities. Not only artificial intelligence, but all technological progress, is such a huge field that it can bring opportunities of all kinds. What needs to be done is to lower the barriers, which is the problem we have. And we also have barriers of many kinds, because we have technical barriers, talent barriers, salary barriers, disciplinary barriers, gender barriers, generational barriers, and so on.

We need to focus energies on lowering those barriers, and then I also think we still come from the analogue world and have little global awareness that both digital and everything that affects AI and data is a global phenomenon. There is no point in keeping it all local, or national, or even European, but it is a global phenomenon. The big problems we have come because we have technology companies that are developed in the United States working in Europe with European citizens' data. A lot of friction is generated there. Anything that can lead to something more global will always be in favour of innovation and will always be in favour of technology. The first thing is to lift the barriers within Europe. That is a very positive part of the law.

7. At this point, we would like to take a look at the state we are in and the prospects for the future. How do you see the future of artificial intelligence in Europe?

Ricard Martínez: I have two visions: one positive and one negative. And both come from my experience in data protection. If now that we have a regulatory framework, the regulatory authorities, I am referring to artificial intelligence and data protection, are not capable of finding functional and grounded solutions, and they generate public policies from the top down and from an excellence that does not correspond to the capacities and possibilities of research - I am referring not only to business research, but also to university research - I see a very dark future. If, on the other hand, we understand regulation in a dynamic way with supportive and accompanying public policies that generate the capacities for this excellence, I see a promising future because in principle what we will do is compete in the market with the same solutions as others, but responsive: safe, responsible and reliable.

Carmen: Yes, I very much agree. I introduce the time variable into that, don't I? Because I think we have to be very careful not to create more inequality than we already have. More inequality among companies, more inequality among citizens. If we are careful with this, which is easy to say but difficult to do, I believe that the future can be bright, but it will not be bright immediately. In other words, we are going to have to go through a darker period of adapting to change. Just as many issues of digitalisation are no longer alien to us, have already been worked on, we have already gone through them and have already regulated them, artificial intelligence also needs its time.

We have had very few years of AI, very few years of generative AI. In fact, two years is nothing in a worldwide technological change. And we have to give time to laws and we also have to give time for things to happen. For example, I give a very obvious example, the New York Times' complaint against Microsoft and OpenAI has not yet been resolved. It's been a year, it was filed in December 2023, the New York Times complains that they have trained AI systems with their content and in a year nothing has been achieved in that process. Court proceedings are very slow. We need more to happen. And that more processes of this type are resolved in order to have precedents and to have maturity as a society in what is happening, and we still have a long way to go. It's like almost nothing has happened. So, the time variable I think is important and I think that, although at the beginning we have a darker future, as Ricard says, I think that in the long term, if we keep clear limits, we can reach something brilliant.

Interview clips

Clip 1. What criteria should the data have to train an AI system?

Clip 2. What should Spanish companies review in light of the IA Regulation?

This episode focuses on data governance and why it is important to have standards, policies and processes in place to ensure that data is correct, reliable, secure and useful. For this purpose, we analyze the Model Ordinance on Data Governance of the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces, known as the FEMP, and its application in a public body such as the City Council of Zaragoza. This will be done by the following guests:

- Roberto Magro Pedroviejo, Coordinator of the Open Data Working Group of the Network of Local Entities for Transparency and Citizen Participation of the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces and civil servant of the Alcobendas City Council.

- María Jesús Fernández Ruiz, Head of the Technical Office of Transparency and Open Government of Zaragoza City Council.

Listen to the full podcast (only available in Spanish)

Summary of the interview

1. What is data governance?

Roberto Magro Pedroviejo: We, in the field of Public Administrations, define data governance as an organisational and technical mechanism that comprehensively addresses issues related to the use of data in our organisation. It covers the entire data lifecycle, i.e. from creation to archiving or even, if necessary, purging and destruction. Its purpose is that data is of quality and available to all those who need it: sometimes it will be only the organisation itself internally, but many other times it will be the general public, re-users, the university environment, etc. Data governance must facilitate the right of access to data. In short, data governance makes it possible to respond to the objective of managing our administration effectively and efficiently and achieving greater interoperability between all administrations.

2. Why is this concept important for a municipality?

María Jesús Fernández Ruiz: Because we have found that, within organisations, both public and private, data collection and management is often carried out without following homogeneous criteria, standards or appropriate techniques. This translates into a difficult and costly situation, which is exacerbated when we try to develop a data space or develop data-related services. Therefore, we need an umbrella that obliges us to manage data, as Roberto has said, effectively and efficiently, following homogeneous standards and criteria, which facilitates interoperability.

3. To meet this challenge, it is necessary to establish a set of guidelines to help local administrations set up a legal framework. For this reason, the FEMP Model Ordinance on Data Governance has been created. What was the process of developing this reference document like?

Roberto Magro Pedroviejo: Within the Open Data Network Group that was created back in 2017, one of the people we have counted on and who has contributed a lot of ideas has been María Jesús, from Zaragoza City Council. We were leaving COVID, just in March 2021, and I remember perfectly the meeting we had in a room lent to us by the Madrid City Council in the Cibeles Palace. María Jesús was in Zaragoza and joined the meeting by videoconference. On that day, seeing what things and what work we could tackle within this multidisciplinary group, María Jesús proposed creating a model ordinance. The FEMP and the Network already had experience in creating model ordinances to try to improve, and above all help, municipalities and local entities or councils to create regulations.

We started working as a multidisciplinary team, led by José Félix Muñoz Soro, from the University of Zaragoza, who is the person who has coordinated the regulatory text that we have published. And a few months later, in January 2022 to be precise, we held a meeting. We met in person at the Zaragoza City Council and there we began to establish the basis for the model ordinance, what type of articles it should have, what type of structure it should have, etc. And we got together a multidisciplinary team, as we said, which included experts in data governance and jurists from the University of Zaragoza, staff from the Polytechnic University of Madrid, colleagues from the Polytechnic University of Valencia, professionals from the local public sphere and journalists who are experts in open data.

The first draft was published in May/June 2022. In addition, it was made available for public consultation through Zaragoza City Council's Citizen Participation platform. We contacted around 100 national experts and received around 30 contributions of improvements, most of which were included, and which allowed us to have the final text by the end of last year, which was passed to the legal department of the FEMP to validate it. The regulations were published in February 2024 and are now available on the Network's website for free download.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the excellent work done by all the people involved in the team who, from their respective points of view, have worked selflessly to create this knowledge and share it with all the Spanish public administrations.

4. What are the expected benefits of the ordinance?

María Jesús Fernández Ruiz: For me, one of the main objectives of the ordinance, and I think it is a great instrument, is that it takes the whole life cycle of the data. It covers from the moment the data is generated, how the data is managed, how the data is provided, how the documentation associated with the data must be stored, how the historical data must be stored, etc. The most important thing is that it establishes criteria for managing the data while respecting its entire life cycle.

The ordinance also establishes some principles, which are not many, but which are very important and which set the tone, which speak, for example, of effective data governance and describe the importance of establishing processes when generating the data, managing the data, providing the data, etc.

Another very important principle, which has been mentioned by Roberto, is the ethical treatment of data. In other words, the importance of collecting data traceability, of seeing where the data is moving and of respecting the rights of natural and legal persons.

Another very important principle that generates a lot of noise in the institutions is that data must be managed from the design phase, the management of data by default. Often, when we start working on data with openness criteria, we are already in the middle or near the end of the data lifecycle. We have to design data management from the beginning, from the source. This saves us a lot of resources, both human and financial.

Another important issue for us and one that we advocate within the ordinance is that administration has to be data-oriented. It has to be an administration that is going to design its policies based on evidence. An administration that will consider data as a strategic asset and will therefore provide the necessary resources.

And another issue, which we often discuss with Roberto, is the importance of data culture. When we work on and publish data, data that is interoperable, that is easy to reuse, that is understood, etc., we cannot stop there, but we must talk about the data culture, which is also included in the ordinance. It is important that we disseminate what is data, what is quality data, how to access data, how to use data. In other words, every time we publish a dataset, we must consider actions related to data culture.

5. Zaragoza City Council has been a pioneer in the application of this ordinance. What has this implementation process been like and what challenges are you facing?

María Jesús Fernández Ruiz: This challenge has been very interesting and has also helped us to improve. It was very fast at the beginning and already in June we were going to present the ordinance to the city government. There is a process where the different parties make private votes on the ordinance and say "this point I like", "this point seems more interesting", "this one should be modified", etc. Our surprise is that we have had more than 50 private votes on the ordinance, after having gone through the public consultation process and having appeared in all the media, which was also enriching, and we have had to respond to these votes. The truth is that it has helped us to improve and, at the moment, we are waiting for it to go to government.

When they tell me how do you feel, María Jesús? The answer is well, we are making progress, because thanks to this ordinance, which is pending approval by the Zaragoza City Council government, we have already issued a series of contracts. One that is extremely important for us: to draw up an inventory of data and information sources in our institution, which we believe is the basic instrument for managing data, knowing what data we have, where they originate, what traceability they have, etc. Therefore, we have not stopped. Thanks to this framework that has not yet been approved, we have been able to make progress on the basis of contracts or something that is basic in an institution: the definition of the professionals who have to participate in data management.

6. You mentioned the need to develop an inventory of datasets and information sources, what kind of datasets are we talking about and what descriptive information should be included for each?

Roberto Magro Pedroviejo: There is a core, let's say a central core, with a series of datasets that we recommend in the ordinance itself, referring to other work done in the open data group, which is to recommend 80 datasets that we could publish in Spanish public administrations. The focus is also on high-value datasets, those that can most benefit municipal management or can benefit by providing social and economic value to the general public and to the business community and reusers. Any administration that wants to start working on the issue of datasets and wonders where to start publishing or managing data has to focus, in my view, on three key areas in a city:

- The personal data, i.e. our beloved census: who are the people living in our city, their ages, gender, postal addresses, etc.

- The urban and territorial data, that is, where these people live, what the territorial delimitation of the municipality is, etc. Everything that has to do with these sets of data related to streets, roads, even sewerage, public roads or lighting, needs to be inventoried, to know where these data are and to have them, as we have already said, updated, structured, accessible, etc.

- And finally, everything that has to do with how the city is managed, of course, with the tax and budget area.

That is: the personal sphere, the territorial sphere and the taxation sphere. That is what we recommend to start with. And in the end, this inventory of datasets describes what they are, where they are, how they are and will be the first basis on which to start building data governance.

María Jesús Fernández Ruiz: Another issue that is also very fundamental, which is included in the ordinance, is to define the master datasets. Just a little anecdote. When creating a spatial data space, the street map, the base cartography and the portal holder are basic. When we got together to work, a technical commission was set up and we considered these to be master datasets for Zaragoza City Council. The quality of the data is determined by a concept in the ordinance, which is respecting the sovereignty of the data: whoever creates the data is the sovereign of the data and is responsible for the quality of the data. Sovereignty must be respected and that determines quality.

We then discovered that, in Zaragoza City Council, we had five different portal identifiers. To improve this situation, we define a descriptive unique identifier which we declare as master data. In this way, all municipal entities will use the same identifier, the same street map, the same cartography, etc. and this will make all services related to the city interoperable.

7. What additional improvements do you think could be included in future revisions of the ordinance?

Roberto Magro Pedroviejo: The ordinance itself, being a regulatory instrument, is adapted to current Spanish and European regulations. In other words, we will have to be very vigilant -we are already - to everything that is being published on artificial intelligence, data spaces and open data. The ordinance will have to be adapted because it is a regulatory framework to comply with current legislation, but if that regulatory framework changes, we will make the appropriate modifications for compliance.

I would also like to highlight two things. There have been more town councils and a university, specifically the Town Council of San Feliu de Llobregat and the University of La Laguna, interested in the ordinance. We have received more requests to know a little more about the ordinance, but the bravest have been the Zaragoza City Council, who were the ones who proposed it and are the ones who are suffering the process of publication and final approval. From this experience that Zaragoza City Council itself is gaining, we will surely all learn, about how to tackle it in each of the administrations, because we copy each other and we can go faster. I believe that, little by little, once Zaragoza publishes the ordinance, other city councils and other institutions will join in. Firstly, because it helps to organise the inside of the house. Now that we are in a process of digital transformation that is not fast, but rather a long process, this type of ordinance will help us, above all, to organise the data we have in the administration. Data and the management of data governance will help us to improve public management within the organisation itself, but above all in terms of the services provided to citizens.

And the last thing I wanted to emphasise, which is also very important, is that, if the data is not of high quality, is not updated and is not metadata-driven, we will do little or nothing in the administration from the point of view of artificial intelligence, because artificial intelligence will be based on the data we have and if it is not correct or updated, the results and predictions that AI can make will be of no use to us in the public administration.

María Jesús Fernández Ruiz: What Roberto has just said about artificial intelligence and quality data is very important. And I would like to add two things that we are learning in implementing this ordinance. Firstly, the need to define processes, i.e. efficient data management has to be based on processes. And another thing that I think we should talk about, and we will talk about within the FEMP, is the importance of defining the roles of the different professionals involved in data management. We are talking about data manager, data provider, technology provider, etc. If I had the ordinance now, I would talk about that definition of the roles that have to be involved in efficient data management. That is, processes and professionals.

Interview clips

Clip 1. What is data governance?

Clip 2. What is the FEMP Model Ordinance on Data Governance?

One of the main requirements of the digital transformation of the public sector concerns the existence of optimal interoperability conditions for data sharing. This is an essential premise from a number of points of view, in particular as regards multi-entity actions and procedures. In particular, interoperability allows:

- The interconnection of the electronic registers powers and the filing of documents with public entities.

- The exchange of data, documents and files in the exercise of the respective competences, which is essential for administrative simplification and, in particular, to guarantee the right not to submit documents already in the possession of the public administrations;

- The development of advanced and personalised services based on the exchange of information, such as the citizen folder.

Interoperability also plays an important role in facilitating the integration of different open data sources for re-use, hence there is even a specific technical standard. It aims to establish common conditions to "facilitate and guarantee the process of re-use of public information from public administrations, ensuring the persistence of the information, the use of formats, as well as the appropriate terms and conditions of use".

Interoperability at European level

Interoperability is therefore a premise for facilitating relations between different entities, which is of particular importance in the European context if we take into account that legal relations will often be between different states. This is therefore a great challenge for the promotion of cross-border digital public services and, consequently, for the enforcement of essential rights and values in the European Union linked to the free movement of persons.

For this reason, the adoption of a regulatory framework to facilitate cross-border data exchange has been promoted to ensure the proper functioning of digital public services at European level. This is Regulation (EU) 2024/903 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 laying down measures for a high level of public sector interoperability across the Union (known as the Interoperable Europe Act), which is directly applicable across the European Union from 12 July 2024.

This regulation aims to provide the right conditions to facilitate cross-border interoperability, which requires an advanced approach to the establishment and management of legal, organisational, semantic and technical requirements. In particular, trans-European digital public services, i.e. those requiring interaction across Member States' borders through their network and information systems, will be affected. This would be the case, for example, for the change of residence to work or study in another Member State, the recognition of academic diplomas or professional qualifications, access to health and social security data or, as regards legal persons, the exchange of tax data or information necessary to participate in a tendering procedure in the field of public procurement. In short, "all those services that apply the "once-only" principle for accessing and exchanging cross-border data".

What are the main measures it envisages?

- Interoperability assessment: prior to decisions on conditions for trans-European digital public services by EU entities or public sector bodies of States, the Regulation requires them to carry out an interoperability assessment, although this will only be mandatory from January 2025. The result of this evaluation shall be published on an official website in a machine-readable format that allows for automatic translation.

- Sharing of interoperability solutions: the above mentioned entities shall be obliged to share interoperability solutions supporting a trans-European digital public service, including technical documentation and source code, as well as references to open standards or technical specifications used. However, there are some limits to this obligation, such as in cases where there are intellectual property rights in favour of third parties. In addition, these solutions will be published on the Interoperable Europe Portal, which will replace the current Joinup portal.

- Enabling of sandboxes: one of the main novelties consists of enabling public bodies to proceed with the creation of sandboxes or controlled interoperability test areas which, in the case of processing personal data, will be managed under the supervision of the corresponding supervisory authority competent to do so. The aim of this figure is to encourage innovation and facilitate cooperation based on the requirements of legal certainty, thereby promoting the development of interoperability solutions based on a better understanding of the opportunities and obstacles that may arise.

- Creation of a governance committee: as regards governance, it is envisaged that a committee will be set up comprising representatives of each of the States and of the Commission, which will be responsible for chairing it. Its main functions include establishing the criteria for interoperability assessment, facilitating the sharing of interoperability solutions, supervising their consistency and developing the European Interoperability Framework, among others. For their part, Member States will have to designate at least one competent authority for the implementation of the Regulation by 12 January 2025, which will act as a single point of contact in case there are several. Its main tasks will be to coordinate the implementation of the Act, to support public bodies in carrying out the assessment and, inter alia, to promote the re-use of interoperability solutions.

The exchange of data between public bodies throughout the European Union and its Member States with full legal guarantees is an essential priority for the effective exercise of their competences and, therefore, for ensuring efficiency in carrying out formalities from the point of view of good administration. The new Interoperable European Regulation is an important step forward in the regulatory framework to further this objective, but the regulation needs to be complemented by a paradigm shift in administrative practice. In this respect, it is essential to make a firm commitment to a document management model based mainly on data, which also makes it easier to deal with regulatory compliance with the regulation on personal data protection, and is also fully coherent with the approach and solutions promoted by the Data Governance Regulation when promoting the re-use of the information generated by public entities in the exercise of their functions.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

On 11, 12 and 13 November, a new edition of DATAforum Justice will be held in Granada. The event will bring together more than 100 speakers to discuss issues related to digital justice systems, artificial intelligence (AI) and the use of data in the judicial ecosystem.The event is organized by the Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts, with the collaboration of the University of Granada, the Andalusian Regional Government, the Granada City Council and the Granada Training and Management entity.

The following is a summary of some of the most important aspects of the conference.

An event aimed at a wide audience

This annual forum is aimed at both public and private sector professionals, without neglecting the general public, who want to know more about the digital transformation of justice in our country.

The DATAforum Justice 2024 also has a specific itinerary aimed at students, which aims to provide young people with valuable tools and knowledge in the field of justice and technology. To this end, specific presentations will be given and a DATAthon will be set up. These activities are particularly aimed at students of law, social sciences in general, computer engineering or subjects related to digital transformation. Attendees can obtain up to 2 ECTS credits (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System): one for attending the conference and one for participating in the DATAthon.

Data at the top of the agenda

The Paraninfo of the University of Granada will host experts from the administration, institutions and private companies, who will share their experience with an emphasis on new trends in the sector, the challenges ahead and the opportunities for improvement.

The conference will begin on Monday 11 November at 9:00 a.m., with a welcome to the students and a presentation of DATAthon. The official inauguration, addressed to all audiences, will be at 11:35 a.m. and will be given by Manuel Olmedo Palacios, Secretary of State for Justice, and Pedro Mercado Pacheco, Rector of the University of Granada.

From then on, various talks, debates, interviews, round tables and conferences will take place, including a large number of data-related topics. Among other issues, the data management, both in administrations and in companies, will be discussed in depth. It will also address the use of open data to prevent everything from hoaxes to suicide and sexual violence.

Another major theme will be the possibilities of artificial intelligence for optimising the sector, touching on aspects such as the automation of justice, the making of predictions. It will include presentations of specific use cases, such as the use of AI for the identification of deceased persons, without neglecting issues such as the governance of algorithms.

The event will end on Wednesday 13 at 17:00 hours with the official closing ceremony. On this occasion, Félix Bolaños, Minister of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Cortes, will accompany the Rector of the University of Granada.

A Datathon to solve industry challenges through data

In parallel to this agenda, a DATAthon will be held in which participants will present innovative ideas and projects to improve justice in our society. It is a contest aimed at students, legal and IT professionals, research groups and startups.

Participants will be divided into multidisciplinary teams to propose solutions to a series of challenges, posed by the organisation, using data science oriented technologies. During the first two days, participants will have time to research and develop their original solution. On the third day, they will have to present a proposal to a qualified jury. The prizes will be awarded on the last day, before the closing ceremony and the Spanish wine and concert that will bring the 2024 edition of DATAfórum Justicia to a close.

In the 2023 edition, 35 people participated, divided into 6 teams that solved two case studies with public data and two prizes of 1,000 euros were awarded.

How to register

The registration period for the DATAforum Justice 2024 is now open. This must be done through the event website, indicating whether it is for the general public, public administration staff, private sector professionals or the media.

To participate in the DATAthon it is necessary to register also on the contest site.

Last year's edition, focusing on proposals to increase efficiency and transparency in judicial systems, was a great success, with over 800 registrants. This year again, a large number of people are expected, so we encourage you to book your place as soon as possible. This is a great opportunity to learn first-hand about successful experiences and to exchange views with experts in the sector.

The strong commitment to common data spaces at European level is one of the main axes of the European Data Strategy adopted in 2020. This approach was already announced in that document as a basis, on the one hand, to support public policy momentum and, on the other hand, to facilitate the development of innovative products and services based on data intelligence and machine learning.

However, the availability of large sectoral datasets required, as an unavoidable prerequisite, an appropriate cross-cutting regulatory framework to establish the conditions for feasibility and security from a legal perspective. In this regard, once the reform of the regulation on the re-use of public sector information had been consolidated, with major innovations such as high-value data, the regulation on data governance was approved in 2022 and then, in 2023, the so-called Data Act. With these initiatives already approved and the recent official publication of the Artificial Intelligence Regulation, the promotion of data spaces is of particular importance, especially in the public sector, in order to ensure the availability of sufficient and quality data.

Data spaces: diversity in their configuration and regulation

The European Data Strategy already envisaged the creation of common European data spaces in a number of sectors and areas of public interest, but at the same time did not rule out the launching of new ones. In fact, in recent years, new spaces have been announced, so that the current number has increased significantly, as we shall see below.

The main reason for data spaces is to facilitate the sharing and exchange of reliable and secure data in strategic economic sectors and areas of public interest. Thus, it is not simply a matter of promoting large datasets but, above all, of supporting initiatives that offer data accessibility according to suitable governance models that, ultimately, allow the interoperability of data throughout the European Union on the basis of appropriate technological infrastructures.

Although general characterisations of data spaces can be offered on the basis of a number of common notes, there is a great diversity from a legal perspective in terms of the purposes they pursue, the conditions under which data are shared and, in particular, the subjects involved.

This heterogeneity is also present in spaces related to the public sector, i.e. those in which there is a prominent role for data generated by administrations and other public entities in the exercise of their functions, to which, therefore, the regulation on reuse and open data approved in 2019 is fully applicable.

Which are the European public sector data spaces?

In early 2024, the second version of a European Commission working document was published with the dual objective of providing an updated overview of the European policy framework for data spaces and also identifying European data space initiatives to assess their maturity and the main challenges ahead for each of them.

In particular, as far as public administrations are concerned, four data spaces are envisaged: the legal data space, the public procurement data space, the data space linked to the technical "once only" system in the context of eGovernment and, finally, the security data space for innovation. These are very diverse initiatives which, moreover, present an uneven degree of maturity, so that some have an advanced level of development and solid institutional support, while other cases are only initially sketched out and have considerable effort ahead for their design and implementation.

Let us take a closer look at each of these spaces referred to in the working paper.

1. Legal data space

It is a data space linked to legislation and jurisprudence generated by both the European Union and the Member States. The aim of this initiative is to support the legal professions, public administrations and, in general, to facilitate access to society in order to strengthen the mechanisms of the rule of law. This space has so far been based on two specific initiatives:

- One concerning information on officially published legislation, which has been articulated through the European Legislation Identifier-ELI. It is a European standard that facilitates the identification of rules in a stable and easily reusable way as it describes legislation with a set of automatically processable metadata, according to a recommended ontology.

- The second concerns decisions taken by judicial bodies, which are made accessible through an European system of unique identifiers called ECLI (European Case Law Identifier) that is assigned to the decisions of both European and national judicial bodies.

These two important initiatives, which facilitate access to and automated processing of legal information, have required a shift from a document-based management model (official gazette, court decisions) to a data-based model. And it is precisely this paradigm shift that has made it possible to offer advanced information services that go beyond the legal and linguistic limits posed by regulatory and linguistic diversity across the European Union.

In any case, while recognising the important progress they represent, there are still important challenges to be faced, such as facilitating access by specific precepts and not by normative documents or, among others, the availability of judicial documents on the basis of the rules they apply and, also, the linking of the rules with their judicial interpretation by the various judicial bodies in all States. In the case of the latter two scenarios, the challenge is even greater, as they would require the automated linking of both identifiers.

2. Public procurement data space

This is undoubtedly one of the areas with the greatest potential impact, given that in the European Union as a whole, it is estimated that public entities spend around two trillion euros (almost 14% of GDP) on the purchase of services, works and supplies. This space is therefore intended not only to facilitate access to the public procurement market across the European Union but also to strengthen transparency and accountability in public procurement spending, which is essential in the fight against corruption and in improving efficiency.

The practical relevance of this space is reinforced by the fact that it has a specific official document that strongly supports the project and sets out a precise roadmap with the objective of ensuring its deployment within a reasonable timeframe. Moreover, despite limitations in its scope of application (there is no provision for extending the publication obligation to contracts below the thresholds set at European level, nor for contract completion notices), it is at a very advanced stage, in particular as regards the availability of a specific ontology which facilitates the accessibility of information and its re-use by reinforcing the conditions for interoperability.

In short, this space is facilitating the automated processing of public procurement data by interconnecting existing datasets, thus providing a more complete picture of public procurement in the European Union as a whole, even though it has been estimated that there are more than 250,000 contracting authorities awarding public contracts.

3. Single Technical System (e-Government)

This new space is intended to support the need that exists in administrative procedures to collect information issued by the administrations of other States, without the interested parties being required to do so directly. It is therefore a matter of automatically and securely gathering the required evidence in a formalised environment based on the direct interconnection between the various public bodies, which will thus act as authentic sources of the required information.

This initiative is linked to the objective of addressing administrative simplification and, in particular, to the implementation of:

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1463 of 5 August 2022 laying down the technical and operational specifications of the technical system for the automated cross-border exchange of evidence and the implementation of the "only once" principle.

- Regulation (EU) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 laying down measures to ensure a high level of public sector interoperability throughout the Union (the Interoperable Europe Regulation), which aims to establish a robust governance structure for interoperability in the public sector.

4. Security data space for innovation

The objective here is to improve law enforcement authorities' access to the data needed to train and validate algorithms with the aim of enhancing the use of artificial intelligence and thus strengthening law enforcement in full respect of ethical and legal standards.

While there is a clear need to facilitate the exchange of data between Member States' law enforcement authorities, the working paper emphasises that this is not a priority for AI strategies in this area, and that the advanced use of data in this area from an innovation perspective is currently relatively low.

In this respect, it is appropriate to highlight the initiative for the development of the Europol sandbox, a project that was sponsored by the decision of the Standing Committee on Operational Cooperation on Internal Security (COSI) to create an isolated space that allows States to develop, train and validate artificial intelligence and machine learning models.

Now that the process of digitisation of public entities is largely consolidated, the main challenge for data spaces in this area is to provide adequate technical, legal and organisational conditions to facilitate data availability and interoperability. In this sense, these data spaces should be taken into account when expanding the list of high-value data, along the lines already advanced by the study published by the European Commission in 2023, which emphasises that the data ets with the greatest potential are those related to government and public administration, justice and legal matters, as well as financial data.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the "Innovation, Law and Technology" Research Group (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Digital transformation has become a fundamental pillar for the economic and social development of countries in the 21st century. In Spain, this process has become particularly relevant in recent years, driven by the need to adapt to an increasingly digitalised and competitive global environment. The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst, accelerating the adoption of digital technologies in all sectors of the economy and society.

However, digital transformation involves not only the incorporation of new technologies, but also a profound change in the way organisations operate and relate to their customers, employees and partners. In this context, Spain has made significant progress, positioning itself as one of the leading countries in Europe in several aspects of digitisation.

The following are some of the most prominent reports analysing this phenomenon and its implications.

State of the Digital Decade 2024 report

The State of the Digital Decade 2024 report examines the evolution of European policies aimed at achieving the agreed objectives and targets for successful digital transformation. It assesses the degree of compliance on the basis of various indicators, which fall into four groups: digital infrastructure, digital business transformation, digital skills and digital public services.

Figure 1. Taking stock of progress towards the Digital Decade goals set for 2030, “State of the Digital Decade 2024 Report”, European Commission.

In recent years, the European Union (EU) has significantly improved its performance by adopting regulatory measures - with 23 new legislative developments, including, among others, the Data Governance Regulation and the Data Regulation- to provide itself with a comprehensive governance framework: the Digital Decade Policy Agenda 2030.

The document includes an assessment of the strategic roadmaps of the various EU countries. In the case of Spain, two main strengths stand out:

- Progress in the use of artificial intelligence by companies (9.2% compared to 8.0% in Europe), where Spain's annual growth rate (9.3%) is four times higher than the EU (2.6%).

- The large number of citizens with basic digital skills (66.2%), compared to the European average (55.6%).

On the other hand, the main challenges to overcome are the adoption of cloud services ( 27.2% versus 38.9% in the EU) and the number of ICT specialists ( 4.4% versus 4.8% in Europe).

The following image shows the forecast evolution in Spain of the key indicators analysed for 2024, compared to the targets set by the EU for 2030.

Figure 2. Key performance indicators for Spain, “Report on the State of the Digital Decade 2024”, European Commission.

Spain is expected to reach 100% on virtually all indicators by 2030. 26.7 billion (1.8 % of GDP), without taking into account private investments. This roadmap demonstrates the commitment to achieving the goals and targets of the Digital Decade.

In addition to investment, to achieve the objective, the report recommends focusing efforts in three areas: the adoption of advanced technologies (AI, data analytics, cloud) by SMEs; the digitisation and promotion of the use of public services; and the attraction and retention of ICT specialists through the design of incentive schemes.

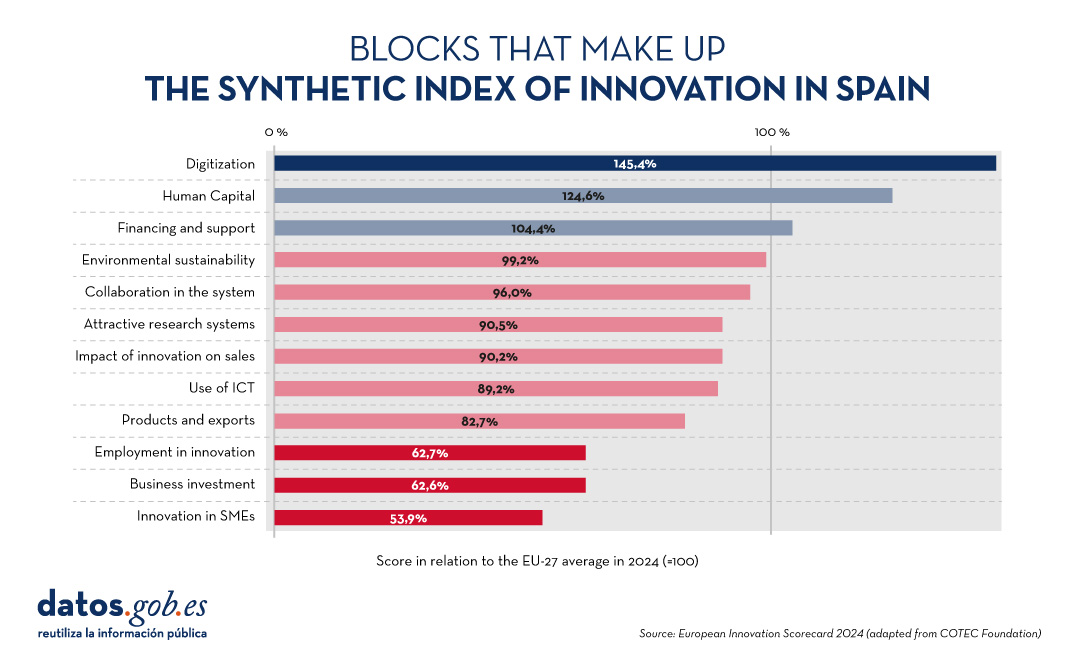

European Innovation Scoreboard 2024

The European Innovation Scoreboard carries out an annual benchmarking of research and innovation developments in a number of countries, not only in Europe. The report classifies regions into four innovation groups, ranging from the most innovative to the least innovative: Innovation Leaders, Strong Innovators, Moderate Innovators and Emerging Innovators.

Spain is leading the group of moderate innovators, with a performance of 89.9% of the EU average. This represents an improvement compared to previous years and exceeds the average of other countries in the same category, which is 84.8%. Our country is above the EU average in three indicators: digitisation, human capital and financing and support. On the other hand, the areas in which it needs to improve the most are employment in innovation, business investment and innovation in SMEs. All this is shown in the following graph:

Figure 3. Blocks that make up the synthetic index of innovation in Spain, European Innovation Scorecard 2024 (adapted from the COTEC Foundation).

Spain's Digital Society Report 2023