Data is a fundamental resource for improving our quality of life because it enables better decision-making processes to create personalised products and services, both in the public and private sectors. In contexts such as health, mobility, energy or education, the use of data facilitates more efficient solutions adapted to people's real needs. However, in working with data, privacy plays a key role. In this post, we will look at how data spaces, the federated computing paradigm and federated learning, one of its most powerful applications, provide a balanced solution for harnessing the potential of data without compromising privacy. In addition, we will highlight how federated learning can also be used with open data to enhance its reuse in a collaborative, incremental and efficient way.

Privacy, a key issue in data management

As mentioned above, the intensive use of data requires increasing attention to privacy. For example, in eHealth, secondary misuse of electronic health record data could violate patients' fundamental rights. One effective way to preserve privacy is through data ecosystems that prioritise data sovereignty, such as data spaces. A dataspace is a federated data management system that allows data to be exchanged reliably between providers and consumers. In addition, the data space ensures the interoperability of data to create products and services that create value. In a data space, each provider maintains its own governance rules, retaining control over its data (i.e. sovereignty over its data), while enabling its re-use by consumers. This implies that each provider should be able to decide what data it shares, with whom and under what conditions, ensuring compliance with its interests and legal obligations.

Federated computing and data spaces

Data spaces represent an evolution in data management, related to a paradigm called federated computing, where data is reused without the need for data flow from data providers to consumers. In federated computing, providers transform their data into privacy-preserving intermediate results so that they can be sent to data consumers. In addition, this enables other Data Privacy-Enhancing Technologies(Privacy-Enhancing Technologies)to be applied. Federated computing aligns perfectly with reference architectures such as Gaia-X and its Trust Framework, which sets out the principles and requirements to ensure secure, transparent and rule-compliant data exchange between data providers and data consumers.

Federated learning

One of the most powerful applications of federated computing is federated machine learning ( federated learning), an artificial intelligence technique that allows models to be trained without centralising data. That is, instead of sending the data to a central server for processing, what is sent are the models trained locally by each participant.

These models are then combined centrally to create a global model. As an example, imagine a consortium of hospitals that wants to develop a predictive model to detect a rare disease. Every hospital holds sensitive patient data, and open sharing of this data is not feasible due to privacy concerns (including other legal or ethical issues). With federated learning, each hospital trains the model locally with its own data, and only shares the model parameters (training results) centrally. Thus, the final model leverages the diversity of data from all hospitals without compromising the individual privacy and data governance rules of each hospital.

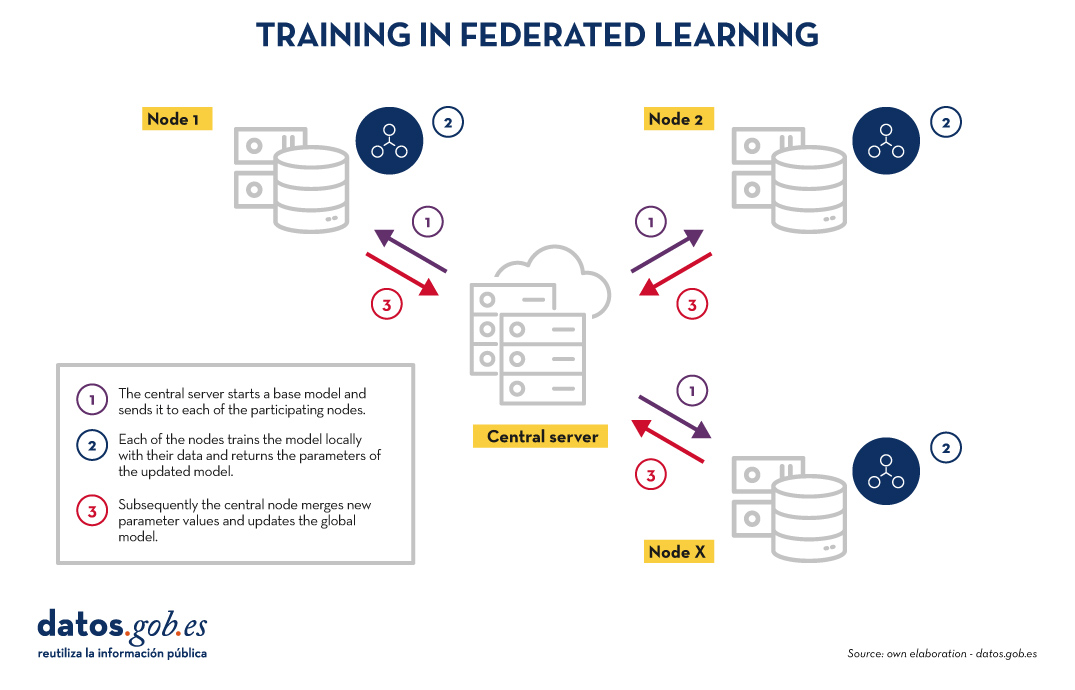

Training in federated learning usually follows an iterative cycle:

- A central server starts a base model and sends it to each of the participating distributed nodes.

- Each node trains the model locally with its data.

- Nodes return only the parameters of the updated model, not the data (i.e. data shuttling is avoided).

- The central server aggregates parameter updates, training results at each node and updates the global model.

- The cycle is repeated until a sufficiently accurate model is achieved.

Figure 1. Visual representing the federated learning training process. Own elaboration

This approach is compatible with various machine learning algorithms, including deep neural networks, regression models, classifiers, etc.

Benefits and challenges of federated learning

Federated learning offers multiple benefits by avoiding data shuffling. Below are the most notable examples:

- Privacy and compliance: by remaining at source, data exposure risks are significantly reduced and compliance with regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is facilitated.

- Data sovereignty: Each entity retains full control over its data, which avoids competitive conflicts.

- Efficiency: avoids the cost and complexity of exchanging large volumes of data, speeding up processing and development times.

- Trust: facilitates frictionless collaboration between organisations.

There are several use cases in which federated learning is necessary, for example:

- Health: Hospitals and research centres can collaborate on predictive models without sharing patient data.

- Finance: banks and insurers can build fraud detection or risk-sharing analysis models, while respecting the confidentiality of their customers.

- Smart tourism: tourist destinations can analyse visitor flows or consumption patterns without the need to unify the databases of their stakeholders (both public and private).

- Industry: Companies in the same industry can train models for predictive maintenance or operational efficiency without revealing competitive data.

While its benefits are clear in a variety of use cases, federated learning also presents technical and organisational challenges:

- Data heterogeneity: Local data may have different formats or structures, making training difficult. In addition, the layout of this data may change over time, which presents an added difficulty.

- Unbalanced data: Some nodes may have more or higher quality data than others, which may skew the overall model.

- Local computational costs: Each node needs sufficient resources to train the model locally.

- Synchronisation: the training cycle requires good coordination between nodes to avoid latency or errors.

Beyond federated learning

Although the most prominent application of federated computing is federated learning, many additional applications in data management are emerging, such as federated data analytics (federated analytics). Federated data analysis allows statistical and descriptive analyses to be performed on distributed data without the need to move the data to the consumers; instead, each provider performs the required statistical calculations locally and only shares the aggregated results with the consumer according to their requirements and permissions. The following table shows the differences between federated learning and federated data analysis.

|

Criteria |

Federated learning |

Federated data analysis |

|

Target |

Prediction and training of machine learning models. | Descriptive analysis and calculation of statistics. |

| Task type | Predictive tasks (e.g. classification or regression). | Descriptive tasks (e.g. means or correlations). |

| Example | Train models of disease diagnosis using medical images from various hospitals. | Calculation of health indicators for a health area without moving data between hospitals. |

| Expected output | Modelo global entrenado. | Resultados estadísticos agregados. |

| Nature | Iterativa. | Directa. |

| Computational complexity | Alta. | Media. |

| Privacy and sovereignty | High | Average |

| Algorithms | Machine learning. | Statistical algorithms. |

Figure 1. Comparative table. Source: own elaboration

Federated learning and open data: a symbiosis to be explored

In principle, open data resolves privacy issues prior to publication, so one would think that federated learning techniques would not be necessary. Nothing could be further from the truth. The use of federated learning techniques can bring significant advantages in the management and exploitation of open data. In fact, the first aspect to highlight is that open data portals such as datos.gob.es or data.europa.eu are federated environments. Therefore, in these portals, the application of federated learning on large datasets would allow models to be trained directly at source, avoiding transfer and processing costs. On the other hand, federated learning would facilitate the combination of open data with other sensitive data without compromising the privacy of the latter. Finally, the nature of a wide variety of open data types is very dynamic (such as traffic data), so federated learning would enable incremental training, automatically considering new updates to open datasets as they are published, without the need to restart costly training processes.

Federated learning, the basis for privacy-friendly AI

Federated machine learning represents a necessary evolution in the way we develop artificial intelligence services, especially in contexts where data is sensitive or distributed across multiple providers. Its natural alignment with the concept of the data space makes it a key technology to drive innovation based on data sharing, taking into account privacy and maintaining data sovereignty.

As regulation (such as the European Health Data Space Regulation) and data space infrastructures evolve, federated learning, and other types of federated computing, will play an increasingly important role in data sharing, maximising the value of data, but without compromising privacy. Finally, it is worth noting that, far from being unnecessary, federated learning can become a strategic ally to improve the efficiency, governance and impact of open data ecosystems.

Jose Norberto Mazón, Professor of Computer Languages and Systems at the University of Alicante. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Language models are at the epicentre of the technological paradigm shift that has been taking place in generative artificial intelligence (AI) over the last two years. From the tools with which we interact in natural language to generate text, images or videos and which we use to create creative content, design prototypes or produce educational material, to more complex applications in research and development that have even been instrumental in winning the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, language models are proving their usefulness in a wide variety of applicationsthat we are still exploring.

Since Google's influential 2017 paper "Attention is all you need" describing the architecture of the Transformers, the technology underpinning the new capabilities that OpenAI popularised in late 2022 with the launch of ChatGPT, the evolution of language models has been more than dizzying. In just two years, we have moved from models focused solely on text generation to multimodal versions that integrate interaction and generation of text, images and audio.

This rapid evolution has given rise to two categories of language models: SLMs (Small Language Models), which are lighter and more efficient, and LLLMs (Large Language Models), which are heavier and more powerful. Far from considering them as competitors, we should analyse SLM and LLM as complementary technologies. While LLLMs offer general processing and content generation capabilities, SLMs can provide support for more agile and specialised solutions for specific needs. However, both share one essential element: they rely on large volumes of data for training and at the heart of their capabilities is open data, which is part of the fuel used to train these language models on which generative AI applications are based.

LLLM: power driven by massive data

The LLLMs are large-scale language models with billions, even trillions, of parameters. These parameters are the mathematical units that allow the model to identify and learn patterns in the training data, giving them an extraordinary ability to generate text (or other formats) that is consistent and adapted to the users' context. These models, such as the GPT family from OpenAI, Gemini from Google or Llama from Meta, are trained on immense volumes of data and are capable of performing complex tasks, some even for which they were not explicitly trained.

Thus, LLMs are able to perform tasks such as generating original content, answering questions with relevant and well-structured information or generating software code, all with a level of competence equal to or higher than humans specialised in these tasks and always maintaining complex and fluent conversations.

The LLLMs rely on massive amounts of data to achieve their current level of performance: from repositories such as Common Crawl, which collects data from millions of web pages, to structured sources such as Wikipedia or specialised sets such as PubMed Open Access in the biomedical field. Without access to these massive bodies of open data, the ability of these models to generalise and adapt to multiple tasks would be much more limited.

However, as LLMs continue to evolve, the need for open data increases to achieve specific advances such as:

- Increased linguistic and cultural diversity: although today's LLMs are multilingual, they are generally dominated by data in English and other major languages. The lack of open data in other languages limits the ability of these models to be truly inclusive and diverse. More open data in diverse languages would ensure that LLMs can be useful to all communities, while preserving the world's cultural and linguistic richness.

- Reducción de sesgos: los LLM, como cualquier modelo de IA, son propensos a reflejar los sesgos presentes en los datos con los que se entrenan. This sometimes leads to responses that perpetuate stereotypes or inequalities. Incorporating more carefully selected open data, especially from sources that promote diversity and equality, is fundamental to building models that fairly and equitably represent different social groups.

- Constant updating: Data on the web and other open resources is constantly changing. Without access to up-to-date data, the LLMs generate outdated responses very quickly. Therefore, increasing the availability of fresh and relevant open data would allow LLMs to keep in line with current events[9].

- Entrenamiento más accesible: a medida que los LLM crecen en tamaño y capacidad, también lo hace el coste de entrenarlos y afinarlos. Open data allows independent developers, universities and small businesses to train and refine their own models without the need for costly data acquisitions. This democratises access to artificial intelligence and fosters global innovation.

To address some of these challenges, the new Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2024 includes measures aimed at generating models and corpora in Spanish and co-official languages, including the development of evaluation datasets that consider ethical evaluation.

SLM: optimised efficiency with specific data

On the other hand, SLMs have emerged as an efficient and specialised alternative that uses a smaller number of parameters (usually in the millions) and are designed to be lightweight and fast. Aunque no alcanzan la versatilidad y competencia de los LLM en tareas complejas, los SLM destacan por su eficiencia computacional, rapidez de implementación y capacidad para especializarse en dominios concretos.

For this, SLMs also rely on open data, but in this case, the quality and relevance of the datasets are more important than their volume, so the challenges they face are more related to data cleaning and specialisation. These models require sets that are carefully selected and tailored to the specific domain for which they are to be used, as any errors, biases or unrepresentativeness in the data can have a much greater impact on their performance. Moreover, due to their focus on specialised tasks, the SLMs face additional challenges related to the accessibility of open data in specific fields. For example, in sectors such as medicine, engineering or law, relevant open data is often protected by legal and/or ethical restrictions, making it difficult to use it to train language models.

The SLMs are trained with carefully selected data aligned to the domain in which they will be used, allowing them to outperform LLMs in accuracy and specificity on specific tasks, such as for example:

- Text autocompletion: a SLM for Spanish autocompletion can be trained with a selection of books, educational texts or corpora such as those to be promoted in the aforementioned AI Strategy, being much more efficient than a general-purpose LLM for this task.

- Legal consultations: a SLM trained with open legal datasets can provide accurate and contextualised answers to legal questions or process contractual documents more efficiently than a LLM.

- Customised education: ein the education sector, SLM trained with open data teaching resources can generate specific explanations, personalised exercises or even automatic assessments, adapted to the level and needs of the student.

- Medical diagnosis: An SLM trained with medical datasets, such as clinical summaries or open publications, can assist physicians in tasks such as identifying preliminary diagnoses, interpreting medical images through textual descriptions or analysing clinical studies.

Ethical Challenges and Considerations

We should not forget that, despite the benefits, the use of open data in language modelling presents significant challenges. One of the main challenges is, as we have already mentioned, to ensure the quality and neutrality of the data so that they are free of biases, as these can be amplified in the models, perpetuating inequalities or prejudices.

Even if a dataset is technically open, its use in artificial intelligence models always raises some ethical implications. For example, it is necessary to avoid that personal or sensitive information is leaked or can be deduced from the results generated by the models, as this could cause damage to the privacy of individuals.

The issue of data attribution and intellectual property must also be taken into account. The use of open data in business models must address how the original creators of the data are recognised and adequately compensated so that incentives for creators continue to exist.

Open data is the engine that drives the amazing capabilities of language models, both SLM and LLM. While the SLMs stand out for their efficiency and accessibility, the LLMs open doors to advanced applications that not long ago seemed impossible. However, the path towards developing more capable, but also more sustainable and representative models depends to a large extent on how we manage and exploit open data.

Contenido elaborado por Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization. Los contenidos y los puntos de vista reflejados en esta publicación son responsabilidad exclusiva de su autor.

The transfer of human knowledge to machine learning models is the basis of all current artificial intelligence. If we want AI models to be able to solve tasks, we first have to encode and transmit solved tasks to them in a formal language that they can process. We understand as a solved task information encoded in different formats, such as text, image, audio or video. In the case of language processing, and in order to achieve systems with a high linguistic competence so that they can communicate with us in an agile way, we need to transfer to these systems as many human productions in text as possible. We call these data sets the corpus.

Corpus: text datasets

When we talk about corpora (its Latin plural) or datasets that have been used to train Large Language Models (LLMs) such as GPT-4, we are talking about books of all kinds, content written on websites, large repositories of text and information in the world such as Wikipedia, but also less formal linguistic productions such as those we write on social networks, in public reviews of products or services, or even in emails. This variety allows these language models to process and handle text in different languages, registers and styles.

For people working in Natural Language Processing (NLP), data science and data engineering, great enablers like Kaggle or repositories like Awesome Public Datasets on GitHub, which provide direct access to download public datasets. Some of these data files have been prepared for processing and are ready for analysis, while others are in an unstructured state, which requires prior cleaning and sorting before they can be worked with. While also containing quantitative numerical data, many of these sources present textual data that can be used to train language models.

The problem of legitimacy

One of the complications we have encountered in creating these models is that text data that is published on the internet and has been collected via API (direct connections that allow mass downloading from a website or repository) or other techniques, are not always in the public domain. In many cases, they are copyrighted: writers, translators, journalists, content creators, scriptwriters, illustrators, designers and also musicians claim licensing fees from the big tech companies for the use of their text and image content to train models. The media, in particular, are actors greatly impacted by this situation, although their positioning varies according to their situation and different business decisions. There is therefore a need for open corpora that can be used for these training tasks, without prejudice to intellectual property.

Characteristics suitable for a training corpus

Most of the characteristics, which have traditionally have traditionally defined a good corpus in linguistic in linguistic research have not changed when these text datasets are now used to train language models.

- It is still beneficial to use whole texts rather than fragments to ensure coherence.

- Texts must be authentic, from linguistic reality and natural language situations, retrievable and verifiable.

- It is important to ensure a wide diversity in the provenance of texts in terms of sectors of society, publications, local varieties of languages and issuers or speakers.

- In addition to general language, a wide variety of specialised language, technical terms and texts specific to different areas of knowledge should be included.

- Register is fundamental in a language, so we must cover both formal and informal register, in its extremes and intermediate regions.

- Language must be well-formed to avoid interference in learning, so it is desirable to remove code marks, numbers or symbols that correspond to digital metadata and not to the natural formation of the language.

Like specific recommendations for the formats of the files that are to form part of these corpora to be part of these corpora, we find that text corpora with annotations should be stored in UTF-8 encoding and in JSON or CSV format, not in PDF. The preferred format of the sound corpus is WAV 16 bit, 16 KHz. (for voice) or 44.1 KHz (for music and audio). Video corpora should be compiled in MPEG-4 (MP4) format, and translation memories in TMX or CSV.

The text as a collective heritage

National libraries in Europe are actively digitising their rich repositories of history and culture, ensuring public access and preservation. Institutions such as the National Library of France or the British Library are leading the way with initiatives that digitise everything from ancient manuscripts to current web publications. This digital hoarding not only protects heritage from physical deterioration, but also democratises access for researchers and the public and, for some years now, also allows the collection of training corpora for artificial intelligence models.

The corpora provided officially by national libraries allow text collections to be used to create public technology available to all: a collective cultural heritage that generates a new collective heritage, this time a technologicalone. The gain is greatest when these institutional corpora do focus on complying with intellectual property laws, providing only open data and texts free of copyright restrictions, with prescribed or licensed rights. This, coupled with the encouraging fact that the amount of real data needed to train language models is hopefully decreasing as technology advances models is decreasing as technology advances, e.g. with the generation ofadvances, for example, with the generation of synthetic data or the optimisation of certain parameters, indicates that it is possible to train large text models without infringing on intellectual property laws operating in Europe.

In particular, the Biblioteca Nacional de España is making a major digitisation effort to make its valuable text repositories available for research, and in particular for language technologies. Since the first major mass digitisation of physical collections in 2008, the BNE has opened up access to millions of documents with the sole aim of sharing and universalising knowledge. In 2023, thanks to investment from the European Union's Recovery, Transformation and Resilience funds, the BNE is promoting a new digital preservation project in its Strategic Plan 2023-2025the plan focuses on four axes:

- the massive and systematic digitisation of collections,

- BNELab as a catalyst for innovation and data reuse in digital ecosystems,

- partnerships and new cooperation environments,

- and technological integration and sustainability.

The alignment of these four axes with new artificial intelligence and natural language processing technologies is more than obvious, as one of the main data reuses is the training of large language models. Both the digitised bibliographic records and the Library's cataloguing indexes are valuable materials for knowledge technology.

Spanish language models

In 2020, as a pioneering and relatively early initiative, in Spain the following was introduced MarIA a language model promoted by the Secretary of State for Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence and developed by the National Supercomputing Centre (BSC-CNS), based on the archives of the National Library of Spain. In this case, the corpus was composed of texts from web pages, which had been collected by the BNE since 2009 and which had served to nourish a model originally based on GPT-2.

A lot has happened between the creation of MarIA and the announcement at the announcement at the 2024 Mobile World Congress of the construction of a great foundational language model, specifically trained in Spanish and co-official languages. This system will be open source and transparent, and will only use royalty-free content in its training. This project is a pioneer at European level, as it seeks to provide an open, public and accessible language infrastructure for companies. Like MarIA, the model will be developed at the BSC-CNS, working together with the Biblioteca Nacional de España and other actors such as the Academia Española de la Lengua and the Asociación de Academias de la Lengua Española.

In addition to the institutions that can provide linguistic or bibliographic collections, there are many more institutions in Spain that can provide quality corpora that can also be used for training models in Spanish. The Study on reusable data as a language resource, published in 2019 within the framework of the Language Technologies Plan, already pointed to different sources: the patents and technical reports of the Spanish and European Patent and Trademark Office, the terminology dictionaries of the Terminology Centre, or data as elementary as the census of the National Statistics Institute, or the place names of the National Geographic Institute. When it comes to audiovisual content, which can be transcribed for reuse, we have the video archive of RTVE A la carta, the Audiovisual Archive of the Congress of Deputies or the archives of the different regional television stations. The Boletín Oficial del Estado itself and its associated materials are an important source of textual information containing extensive knowledge about our society and its functioning. Finally, in specific areas such as health or justice, we have the publications of the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products, the jurisprudence texts of the CENDOJ or the recordings of court hearings of the General Council of the Judiciary.

European initiatives

In Europe there does not seem to be as clear a precedent as MarIA or the upcoming GPT-based model in Spanish, as state-driven projects trained with heritage data, coming from national libraries or official bodies.

However, in Europe there is good previous work on the availability of documentation that could now be used to train European-founded AI systems. A good example is the europeana project, which seeks to digitise and make accessible the cultural and artistic heritage of Europe as a whole. It is a collaborative initiative that brings together contributions from thousands of museums, libraries, archives and galleries, providing free access to millions of works of art, photographs, books, music pieces and videos. Europeana has almost 25 million documents in text, which could be the basis for creating multilingual or multilingual competent foundational models in the different European languages.

There are also non-governmental initiatives, but with a global impact, such as Common Corpus which are the ultimate proof that it is possible to train language models with open data and without infringing copyright laws. Common Corpus was released in March 2024, and is the largest dataset created for training large language models, with 500 billion words from various cultural heritage initiatives. This corpus is multilingual and is the largest to date in English, French, Dutch, Spanish, German, Italian and French.

And finally, beyond text, it is possible to find initiatives in other formats such as audio, which can also be used to train AI models. In 2022, the National Library of Sweden provided a sound corpus of more than two million hours of recordings from local public radio, podcasts and audiobooks. The aim of the project was to generate an AI-based model of language-competent audio-to-text transcription that maximises the number of speakers to achieve a diverse and democratic dataset available to all.

Until now, the sense of collectivity and heritage has been sufficient in collecting and making data in text form available to society. With language models, this openness achieves a greater benefit: that of creating and maintaining technology that brings value to people and businesses, fed and enhanced by our own linguistic productions.

Content prepared by Carmen Torrijos, expert in AI applied to language and communication. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.