Cities, infrastructures and the environment today generate a constant flow of data from sensors, transport networks, weather stations and Internet of Things (IoT) platforms, understood as networks of physical devices (digital traffic lights, air quality sensors, etc.) capable of measuring and transmitting information through digital systems. This growing volume of information makes it possible to improve the provision of public services, anticipate emergencies, plan the territory and respond to challenges associated with climate, mobility or resource management.

The increase in connected sources has transformed the nature of geospatial data. In contrast to traditional sets – updated periodically and oriented towards reference cartography or administrative inventories – dynamic data incorporate the temporal dimension as a structural component. An observation of air quality, a level of traffic occupancy or a hydrological measurement not only describes a phenomenon, but also places it at a specific time. The combination of space and time makes these observations fundamental elements for operating systems, predictive models and analyses based on time series.

In the field of open data, this type of information poses both opportunities and specific requirements. Opportunities include the possibility of building reusable digital services, facilitating near-real-time monitoring of urban and environmental phenomena, and fostering a reuse ecosystem based on continuous flows of interoperable data. The availability of up-to-date data also increases the capacity for evaluation and auditing of public policies, by allowing decisions to be contrasted with recent observations.

However, the opening of geospatial data in real time requires solving problems derived from technological heterogeneity. Sensor networks use different protocols, data models, and formats; the sources generate high volumes of observations with high frequency; and the absence of common semantic structures makes it difficult to cross-reference data between domains such as mobility, environment, energy or hydrology. In order for this data to be published and reused consistently, an interoperability framework is needed that standardizes the description of observed phenomena, the structure of time series, and access interfaces.

The open standards of the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) provide that framework. They define how to represent observations, dynamic entities, multitemporal coverages or sensor systems; establish APIs based on web principles that facilitate the consultation of open data; and allow different platforms to exchange information without the need for specific integrations. Its adoption reduces technological fragmentation, improves coherence between sources and favours the creation of public services based on up-to-date data.

Interoperability: The basic requirement for opening dynamic data

Public administrations today manage data generated by sensors of different types, heterogeneous platforms, different suppliers and systems that evolve independently. The publication of geospatial data in real time requires interoperability that allows information from multiple sources to be integrated, processed and reused. This diversity causes inconsistencies in formats, structures, vocabularies and protocols, which makes it difficult to open the data and reuse it by third parties. Let's see which aspects of interoperability are affected:

- Technical interoperability: refers to the ability of systems to exchange data using compatible interfaces, formats and models. In real-time data, this exchange requires mechanisms that allow for fast queries, frequent updates, and stable data structures. Without these elements, each flow would rely on ad hoc integrations, increasing complexity and reducing reusability.

- The Semantic interoperability: Dynamic data describe phenomena that change over short periods – traffic levels, weather parameters, flows, atmospheric emissions – and must be interpreted consistently. This implies having observation models, Vocabularies and common definitions that allow different applications to understand the meaning of each measurement and its units, capture conditions or constraints. Without this semantic layer, the opening of data in real time generates ambiguity and limits its integration with data from other domains.

- Structural interoperability: Real-time data streams tend to be continuous and voluminous, making it necessary to represent them as time series or sets of observations with consistent attributes. The absence of standardized structures complicates the publication of complete data, fragments information and prevents efficient queries. To provide open access to these data, it is necessary to adopt models that adequately represent the relationship between observed phenomenon, time of observation, associated geometry and measurement conditions.

- Interoperability in access via API: it is an essential condition for open data. APIs must be stable, documented, and based on public specifications that allow for reproducible queries. In the case of dynamic data, this layer guarantees that the flows can be consumed by external applications, analysis platforms, mapping tools or monitoring systems that operate in contexts other than the one that generates the data. Without interoperable APIs, real-time data is limited to internal uses.

Together, these levels of interoperability determine whether dynamic geospatial data can be published as open data without creating technical barriers.

OGC Standards for Publishing Real-Time Geospatial Data

The publication of georeferenced data in real time requires mechanisms that allow any user – administration, company, citizens or research community – to access them easily, with open formats and through stable interfaces. The Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) develops a set of standards that enable exactly this: to describe, organize and expose spatial data in an interoperable and accessible way, which contributes to the openness of dynamic data.

What is OGC and why are its standards relevant?

The OGC is an international organization that defines common rules so that different systems can understand, exchange and use geospatial data without depending on specific technologies. These rules are published as open standards, which means that any person or institution can use them. In the realm of real-time data, these standards make it possible to:

- Represent what a sensor measures (e.g., temperature or traffic).

- Indicate where and when the observation was made.

- Structure time series.

- Expose data through open APIs.

- Connect IoT devices and networks with public platforms.

Together, this ecosystem of standards allows geospatial data – including data generated in real time – to be published and reused following a consistent framework. Each standard covers a specific part of the data cycle: from the definition of observations and sensors, to the way data is exposed using open APIs or web services. This modular organization makes it easier for administrations and organizations to select the components they need, avoiding technological dependencies and ensuring that data can be integrated between different platforms.

The OGC API family: Modern APIs for accessing open data

Within OGC, the newest line is family OGC API, a set of modern web interfaces designed to facilitate access to geospatial data using URLs and formats such as JSON or GeoJSON, common in the open data ecosystem.

Estas API permiten:

- Get only the part of the data that matters.

- Perform spatial searches ("give me only what's in this area").

- Access up-to-date data without the need for specialized software.

- Easily integrate them into web or mobile applications.

In this report: "How to use OGC APIs to boost geospatial data interoperability", we already told you about some of the most popular OGP APIs. While the report focuses on how to use OGC APIs for practical interoperability, this post expands the focus by explaining the underlying OGC data models—such as O&M, SensorML, or Moving Features—that underpin that interoperability.

On this basis, this post focuses on the standards that make this fluid exchange of information possible, especially in open data and real-time contexts. The most important standards in the context of real-time open data are:

|

OGC Standard |

What it allows you to do |

Primary use in open data |

|---|---|---|

|

OGC API – Features |

Query features with geometry; filter by time or space; get data in JSON/GeoJSON. |

Open publication of dynamic mobility data, urban inventories, static sensors. |

|

OGC API – Environmental Data Retrieval (EDR) |

Request environmental observations at a point, zone or time interval. |

Open data on meteorology, climate, air quality or hydrology. |

|

OGC SensorThings API |

Manage sensors and their time series; transmit large volumes of IoT data. |

Publication of urban sensors (air, noise, water, energy) in real time. |

|

OGC API – Connected Systems |

Describe networks of sensors, devices and associated infrastructures. |

Document the structure of municipal IoT systems as open data. |

|

OGC Moving Features |

Represent moving objects using space-time trajectories. |

Open mobility data (vehicles, transport, boats). |

|

WMS-T |

View maps that change over time. |

Publication of multi-temporal weather or environmental maps. |

Table 1. OGC Standards Relevant to Real-Time Geospatial Data

Models that structure observations and dynamic data

In addition to APIs, OGC defines several conceptual data models that allow you to consistently describe observations, sensors, and phenomena that change over time:

- O&M (Observations & Measurements): A model that defines the essential elements of an observation—measured phenomenon, instant, unity, and result—and serves as the semantic basis for sensor and time series data.

- SensorML: Language that describes the technical and operational characteristics of a sensor, including its location, calibration, and observation process.

- Moving Features: A model that allows mobile objects to be represented by means of space-time trajectories (such as vehicles, boats or fauna).

These models make it easy for different data sources to be interpreted uniformly and combined in analytics and applications.

The value of these standards for open data

Using OGC standards makes it easier to open dynamic data because:

- It provides common models that reduce heterogeneity between sources.

- It facilitates integration between domains (mobility, climate, hydrology).

- Avoid dependencies on proprietary technology.

- It allows the data to be reused in analytics, applications, or public services.

- Improves transparency by documenting sensors, methods, and frequencies.

- It ensures that data can be consumed directly by common tools.

Together, they form a conceptual and technical infrastructure that allows real-time geospatial data to be published as open data, without the need to develop system-specific solutions.

Real-time open geospatial data use cases

Real-time georeferenced data is already published as open data in different sectoral areas. These examples show how different administrations and bodies apply open standards and APIs to make dynamic data related to mobility, environment, hydrology and meteorology available to the public.

Below are several domains where Public Administrations already publish dynamic geospatial data using OGC standards.

Mobility and transport

Mobility systems generate data continuously: availability of shared vehicles, positions in near real-time, sensors for crossing in cycle lanes, traffic gauging or traffic light intersection status. These observations rely on distributed sensors and require data models capable of representing rapid variations in space and time.

OGC standards play a central role in this area. In particular, the OGC SensorThings API allows you to structure and publish observations from urban sensors using a uniform model – including devices, measurements, time series and relationships between them – accessible through an open API. This makes it easier for different operators and municipalities to publish mobility data in an interoperable way, reducing fragmentation between platforms.

The use of OGC standards in mobility not only guarantees technical compatibility, but also makes it possible for this data to be reused together with environmental, cartographic or climate information, generating multi-thematic analyses for urban planning, sustainability or operational transport management.

Example:

The open service of Toronto Bike Share, which publishes in SensorThings API format the status of its bike stations and vehicle availability.

Here each station is a sensor and each observation indicates the number of bicycles available at a specific time. This approach allows analysts, developers or researchers to integrate this data directly into urban mobility models, demand prediction systems or citizen dashboards without the need for specific adaptations.

Air quality, noise and urban sensors

Networks for monitoring air quality, noise or urban environmental conditions depend on automatic sensors that record measurements every few minutes. In order for this data to be integrated into analytics systems and published as open data, consistent models and APIs need to be available.

In this context, services based on OGC standards make it possible to publish data from fixed stations or distributed sensors in an interoperable way. Although many administrations use traditional interfaces such as OGC WMS to serve this data, the underlying structure is usually supported by observation models derived from the Observations & Measurements (O&M) family, which defines how to represent a measured phenomenon, its unit and the moment of observation.

Example:

The service Defra UK-AIR Sensor Observation Service provides access to near-real-time air quality measurement data from on-site stations in the UK.

The combination of O&M for data structure and open APIs for publication makes it easier for these urban sensors to be part of broader ecosystems that integrate mobility, meteorology or energy, enabling advanced urban analyses or environmental dashboards in near real-time.

Water cycle, hydrology and risk management

Hydrological systems generate crucial data for risk management: river levels and flows, rainfall, soil moisture or information from hydrometeorological stations. Interoperability is especially important in this domain, as this data is combined with hydraulic models, weather forecasting, and flood zone mapping.

To facilitate open access to time series and hydrological observations, several agencies use OGC API – Environmental Data Retrieval (EDR), an API designed to retrieve environmental data using simple queries at points, areas, or time intervals.

Example:

The USGS (United States Geological Survey), which documents the use of OGC API – EDR to access precipitation, temperature, or hydrological variable series.

This case shows how EDR allows you to request specific observations by location or date, returning only the values needed for analysis. While the USGS's specific hydrology data is served through its proprietary API, this case demonstrates how EDR fits into the hydrometeorological data structure and how it is applied in real operational flows.

The use of OGC standards in this area allows dynamic hydrological data to be integrated with flood zones, orthoimages or climate models, creating a solid basis for early warning systems, hydraulic planning and risk assessment.

Weather observation and forecasting

Meteorology is one of the domains with the highest production of dynamic data: automatic stations, radars, numerical prediction models, satellite observations and high-frequency atmospheric products. To publish this information as open data, the OGC API family is becoming a key element, especially through OGC API – EDR, which allows observations or predictions to be retrieved in specific locations and at different time levels.

Example:

The service NOAA OGC API – EDR, which provides access to weather data and atmospheric variables from the National Weather Service (United States).

This API allows data to be consulted at points, areas or trajectories, facilitating the integration of meteorological observations into external applications, models or services based on open data.

The use of OGC API in meteorology allows data from sensors, models, and satellites to be consumed through a unified interface, making it easy to reuse for forecasting, atmospheric analysis, decision support systems, and climate applications.

Best Practices for Publishing Open Geospatial Data in Real-Time

The publication of dynamic geospatial data requires adopting practices that ensure its accessibility, interoperability, and sustainability. Unlike static data, real-time streams have additional requirements related to the quality of observations, API stability, and documentation of the update process. Here are some best practices for governments and organizations that manage this type of data.

- Stable open formats and APIs: The use of OGC standards – such as OGC API, SensorThings API or EDR – makes it easy for data to be consumed from multiple tools without the need for specific adaptations. APIs must be stable over time, offer well-defined versions, and avoid dependencies on proprietary technologies. For raster data or dynamic models, OGC services such as WMS, WMTS, or WCS are still suitable for visualization and programmatic access.

- DCAT-AP and OGC Models Compliant Metadata: Catalog interoperability requires describing datasets using profiles such as DCAT-AP, supplemented by O&M-based geospatial and observational metadata or SensorML. This metadata should document the nature of the sensor, the unit of measurement, the sampling rate, and possible limitations of the data.

- Quality, update frequency and traceability policies: dynamic datasets must explicitly indicate their update frequency, the origin of the observations, the validation mechanisms applied and the conditions under which they were generated. Traceability is essential for third parties to correctly interpret data, reproduce analyses and integrate observations from different sources.

- Documentation, usage limits, and service sustainability: Documentation should include usage examples, query parameters, response structure, and recommendations for managing data volume. It is important to set reasonable query limits to ensure the stability of the service and ensure that management can maintain the API over the long term.

- Licensing aspects for dynamic data: The license must be explicit and compatible with reuse, such as CC BY 4.0 or CC0. This allows dynamic data to be integrated into third-party services, mobile applications, predictive models or services of public interest without unnecessary restrictions. Consistency in the license also facilitates the cross-referencing of data from different sources.

These practices allow dynamic data to be published in a way that is reliable, accessible, and useful to the entire reuse community.

Dynamic geospatial data has become a structural piece for understanding urban, environmental and climatic phenomena. Its publication through open standards allows this information to be integrated into public services, technical analyses and reusable applications without the need for additional development. The convergence of observation models, OGC APIs, and best practices in metadata and licensing provides a stable framework for administrations and reusers to work with sensor data reliably. Consolidating this approach will allow progress towards a more coherent, connected public data ecosystem that is prepared for increasingly demanding uses in mobility, energy, risk management and territorial planning.

Content created by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Technologies related to the data economy. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Data is the engine of innovation, and its transformative potential is reflected in all areas, especially in health. From faster diagnoses to personalized treatments to more effective public policies, the intelligent use of health information has the power to change lives in profound and meaningful ways.

But, for this data to unfold its full value and become a real force for progress, it is essential that it "speaks the same language". That is, they must be well organized, easy to find, and can be shared securely and consistently across systems, countries, and practitioners.

This is where HealthDCAT-AP comes into play, a new European specification that, although it sounds technical, has a lot to do with our well-being as citizens. HealthDCAT-AP is designed to describe health data—from aggregated statistics to anonymized clinical records—in a homogeneous, clear, and reusable way, through metadata. In short, it does not act on the clinical data itself, but rather makes it easier for them to be located and better understood thanks to a standardized description.HealthDCAT-AP is exclusively concerned with metadata, i.e., how datasets are described and organized in catalogs, unlike HL7, FHIR, and DICOM, which structure the exchange of clinical information and images. CDA, which describes the architecture of documents; and SNOMED CT, LOINC, and ICD-10, which standardize the semantics of diagnoses, procedures, and observations to ensure that data have the same meaning in any context.

This article explores how HealthDCAT-AP, in the context of the European Health Data Space (EHDS) and the National Health Data Space (ENDS), brings value primarily to those who reuse data—such as researchers, innovators, or policymakers—and ultimately benefits citizens through the advances they generate.

What is HealthDCAT-AP and how does it relate to DCAT-AP?

Imagine a huge library full of health books, but without any system to organize them. Searching for specific information would be a chaotic task. Something similar happens with health data: if it is not well described, locating and reusing it is practically impossible.

HealthDCAT-AP was born to solve this challenge. It is a European technical specification that allows for a clear and uniform description of health datasets within data catalogues, making it easier to search, access, understand and reuse them. In other words, it makes the description of health data speak the same language across Europe, which is key to improving health care, research and policy.

This technical specification is based on DCAT-AP, the general specification used to describe catalogues of public sector datasets in Europe. While DCAT-AP provides a common structure for all types of data, HealthDCAT-AP is your specialized health extension, adapting and extending that model to cover the particularities of clinical, epidemiological, or biomedical data.

HealthDCAT-AP was developed within the framework of the European EHDS2 (European Health Data Space 2) pilot project and continues to evolve thanks to the support of projects such as HealthData@EU Pilot, which are working on the deployment of the future European health data infrastructure. The specification is under active development and its most recent version, along with documentation and examples, can be publicly consulted in its official GitHub repository.

HealthDCAT-AP is also designed to apply the FAIR principles: that data is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable. This means that although health data may be complex or sensitive, its description (metadata) is clear, standardized, and useful. Any professional or institution – whether in Spain or in another European country – can know what data exists, how to access it and under what conditions. This fosters trust, transparency, and responsible use of health data. HealthDCAT-AP is also a cornerstone of EHDS and therefore ENDS. Its adoption will allow hospitals, research centres or administrations to share information consistently and securely across Europe. Thus, collaboration between countries is promoted and the value of data is maximized for the benefit of all citizens.

To facilitate its use and adoption, from Europe, under the initiatives mentioned above, tools such as the HealthDCAT-AP editor and validator have been created, which allow any organization to generate descriptions of datasets through metadata that are compatible without the need for advanced technical knowledge. This removes barriers and encourages more entities to participate in this networked health data ecosystem.

How does HealthDCAT-AP contribute to the public value of health data?

Although HealthDCAT-AP is a technical specification focused on the description of health datasets, its adoption has practical implications that go beyond the technological realm. By offering a common and structured way of documenting what data exists, how it can be used and under what conditions, it helps different actors – from hospitals and administrations to research centres or startups – to better access, combine and reuse the available information, enabling the so-called secondary use of the same, beyond its primary healthcare use.

- Faster diagnoses and personalized treatments: When data is well-organized and accessible to those who need it, advances in medical research accelerate. This makes it possible to develop artificial intelligence tools that detect diseases earlier, identify patterns in large populations and adapt treatments to the profile of each patient. It is the basis of personalized medicine, which improves results and reduces risks.

- Better access to knowledge about what data exists: HealthDCAT-AP makes it easier for researchers, healthcare managers or authorities to locate useful datasets, thanks to its standardized description. This can facilitate, for example, the analysis of health inequalities or resource planning in crisis situations.

- Greater transparency and traceability: The use of metadata allows us to know who is responsible for each set of data, for what purpose it can be used and under what conditions. This strengthens trust in the data reuse ecosystem.

- More efficient healthcare services: Standardizing metadata improves information flows between sites, regions, and systems. This reduces bureaucracy, avoids duplication, optimizes the use of resources, and frees up time and money that can be reinvested in improving direct patient care.

- More innovation and new solutions for the citizen: by facilitating access to larger datasets, HealthDCAT-AP promotes the development of new patient-centric digital tools: self-care apps, remote monitoring systems, service comparators, etc. Many of these solutions are born outside the health system – in universities, startups or associations – but directly benefit citizens.

- A connected Europe around health: By sharing a common way of describing data, HealthDCAT-AP makes it possible for a dataset created in Spain to be understood and used in Germany or Finland, and vice versa. This promotes international collaboration, strengthens European cohesion and ensures that citizens benefit from scientific advances regardless of their country.

And what role does Spain play in all this?

Spain is not only aligned with the future of health data in Europe: it is actively participating in its construction. Thanks to a solid legal foundation, a largely digitized healthcare system, accumulated experience in the secure sharing of health information within the Spanish National Health System (SNS), and a long history of open data—through initiatives such as datos.gob.es—our country is in a privileged position to contribute to and benefit from the European Health Data Space (EHDS).

Over the years, Spain has developed legal frameworks and technical capacities that anticipate many of the requirements of the EHDS Regulation. The widespread digitalization of healthcare and the experience in using data in a secure and responsible way allow us to move towards an interoperable, ethical and common good-oriented model.

In this context, the National Health Data Space project represents a decisive step forward. This initiative aims to become the national reference platform for the analysis and exploitation of health data for secondary use, conceived as a catalyst for research and innovation in health, a benchmark in the application of disruptive solutions, and a gateway to different data sources. All of this is carried out under strict conditions of anonymization, security, transparency, and protection of rights, ensuring that the data is only used for legitimate purposes and in full compliance with current regulations.

Spain's familiarity with standards such as DCAT-AP facilitates the deployment of HealthDCAT-AP. Platforms such as datos.gob.es, which already act as a reference point for the publication of open data, will be key in its deployment and dissemination.

Conclusions

HealthDCAT-AP may sound technical, but it is actually a specification that can have an impact on our daily lives. By helping to better describe health data, it makes it easier for that information to be used in a useful, safe, and responsible manner.

This specification allows the description of data sets to speak the same language across Europe. This makes it easier to find, share with the right people, and reuse for purposes that benefit us all: faster diagnoses, more personalized treatments, better public health decisions, and new digital tools that improve our quality of life.

Spain, thanks to its experience in open data and its digitized healthcare system, is actively participating in this transformation through a joint effort between professionals, institutions, companies, researchers, etc., and also citizens. Because when data is understood and managed well, it can make a difference. It can save time, resources, and even lives.

HealthDCAT-AP is not just a technical specification: it is a step forward towards more connected, transparent, and people-centered healthcare. A specification designed to maximize the secondary use of health information, so that all of us as citizens can benefit from it.

Content created by Dr. Fernando Gualo, Professor at UCLM and Government and Data Quality Consultant. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

One of the main requirements of the digital transformation of the public sector concerns the existence of optimal interoperability conditions for data sharing. This is an essential premise from a number of points of view, in particular as regards multi-entity actions and procedures. In particular, interoperability allows:

- The interconnection of the electronic registers powers and the filing of documents with public entities.

- The exchange of data, documents and files in the exercise of the respective competences, which is essential for administrative simplification and, in particular, to guarantee the right not to submit documents already in the possession of the public administrations;

- The development of advanced and personalised services based on the exchange of information, such as the citizen folder.

Interoperability also plays an important role in facilitating the integration of different open data sources for re-use, hence there is even a specific technical standard. It aims to establish common conditions to "facilitate and guarantee the process of re-use of public information from public administrations, ensuring the persistence of the information, the use of formats, as well as the appropriate terms and conditions of use".

Interoperability at European level

Interoperability is therefore a premise for facilitating relations between different entities, which is of particular importance in the European context if we take into account that legal relations will often be between different states. This is therefore a great challenge for the promotion of cross-border digital public services and, consequently, for the enforcement of essential rights and values in the European Union linked to the free movement of persons.

For this reason, the adoption of a regulatory framework to facilitate cross-border data exchange has been promoted to ensure the proper functioning of digital public services at European level. This is Regulation (EU) 2024/903 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 laying down measures for a high level of public sector interoperability across the Union (known as the Interoperable Europe Act), which is directly applicable across the European Union from 12 July 2024.

This regulation aims to provide the right conditions to facilitate cross-border interoperability, which requires an advanced approach to the establishment and management of legal, organisational, semantic and technical requirements. In particular, trans-European digital public services, i.e. those requiring interaction across Member States' borders through their network and information systems, will be affected. This would be the case, for example, for the change of residence to work or study in another Member State, the recognition of academic diplomas or professional qualifications, access to health and social security data or, as regards legal persons, the exchange of tax data or information necessary to participate in a tendering procedure in the field of public procurement. In short, "all those services that apply the "once-only" principle for accessing and exchanging cross-border data".

What are the main measures it envisages?

- Interoperability assessment: prior to decisions on conditions for trans-European digital public services by EU entities or public sector bodies of States, the Regulation requires them to carry out an interoperability assessment, although this will only be mandatory from January 2025. The result of this evaluation shall be published on an official website in a machine-readable format that allows for automatic translation.

- Sharing of interoperability solutions: the above mentioned entities shall be obliged to share interoperability solutions supporting a trans-European digital public service, including technical documentation and source code, as well as references to open standards or technical specifications used. However, there are some limits to this obligation, such as in cases where there are intellectual property rights in favour of third parties. In addition, these solutions will be published on the Interoperable Europe Portal, which will replace the current Joinup portal.

- Enabling of sandboxes: one of the main novelties consists of enabling public bodies to proceed with the creation of sandboxes or controlled interoperability test areas which, in the case of processing personal data, will be managed under the supervision of the corresponding supervisory authority competent to do so. The aim of this figure is to encourage innovation and facilitate cooperation based on the requirements of legal certainty, thereby promoting the development of interoperability solutions based on a better understanding of the opportunities and obstacles that may arise.

- Creation of a governance committee: as regards governance, it is envisaged that a committee will be set up comprising representatives of each of the States and of the Commission, which will be responsible for chairing it. Its main functions include establishing the criteria for interoperability assessment, facilitating the sharing of interoperability solutions, supervising their consistency and developing the European Interoperability Framework, among others. For their part, Member States will have to designate at least one competent authority for the implementation of the Regulation by 12 January 2025, which will act as a single point of contact in case there are several. Its main tasks will be to coordinate the implementation of the Act, to support public bodies in carrying out the assessment and, inter alia, to promote the re-use of interoperability solutions.

The exchange of data between public bodies throughout the European Union and its Member States with full legal guarantees is an essential priority for the effective exercise of their competences and, therefore, for ensuring efficiency in carrying out formalities from the point of view of good administration. The new Interoperable European Regulation is an important step forward in the regulatory framework to further this objective, but the regulation needs to be complemented by a paradigm shift in administrative practice. In this respect, it is essential to make a firm commitment to a document management model based mainly on data, which also makes it easier to deal with regulatory compliance with the regulation on personal data protection, and is also fully coherent with the approach and solutions promoted by the Data Governance Regulation when promoting the re-use of the information generated by public entities in the exercise of their functions.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

One of the main objectives of Regulation (EU) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules for fair access to and use of data (Data Regulation) is to promote the development of interoperability criteria for data spaces, data processing services and smart contracts. In this respect, the Regulation understands interoperability as:

The ability of two or more data spaces or communication networks, systems, connected products, applications, data processing services or components to exchange and use data to perform their functions.

It explicitly states that 'interoperable and high quality data from different domains increase competitiveness and innovationand ensure sustainable economic growth', which requires that 'the same data can be used and reused for different purposes and in an unlimited way, without loss of quality or quantity'. It therefore believes that "a regulatory approach to interoperability that is ambitious and inspires innovation is essential toovercome the dependence on a single provider, which hinders competition and the development of new services".

Interoperability and data spaces

This concern already existed in the European Data Strategy where interoperability was seen as a key element for the valorisation of data and, in particular, for the deployment of Artificial Intelligence. In fact, interoperability is an unavoidable premise for data spaces, so that the establishment of appropriate protocols becomes essential to ensure their potential, both for each of the data spaces internally and also in order to facilitate a cross-cutting integration of several of them.

In this sense, there are frequent standardisation initiatives and meetings to try to establish specific interoperability conditions in this type of scenario, characterised by the diversity of data sources. Although this is an added difficulty, a cross-cutting approach, integrating several data spaces, provides a greater impact on the generation of value-added services and creates the right legal conditions for innovation.

According to the Data Regulation, those who participate in data spaces and offer data or data services to other actors involved in data spaces have to comply with a number of requirements aimed precisely at ensuring appropriate conditions for interoperability and thus that data can be processed jointly. To this end, a description of the content, structure, format and other conditions of use of the data shall be provided in such a way as to facilitate access to and sharing of the data in an automated manner, including in real time or allowing bulk downloading where appropriate.

It should be noted that compliance with technical and semantic standards for interoperability is essential for data spaces, since a minimum standardisation of legal conditions greatly facilitates their operation. In particular, it is of great importance to ensure that the data provider holds the necessary rights to share the data in such an environment and to be able to prove this in an automated way

Interoperability in data processing services

The Data Regulation pays particular attention to the need to improve interoperability between different data processing service providers, so that customers can benefit from the interaction between each of them, thereby reducing dependency on individual providers.

To this end, firstly, it reinforces the reporting obligations of providers of this type of services, to which must be added those derived from the general regulation on the provision of digital content and services general regulation on the provision of digital content and services. In particular, they must be in writing:

- Contractual conditions relating to customer rights, especially in situations related to a possible switch to another provider or infrastructure.

- A full indication of the data that may be exported during the switching process, so that the scope of the interoperability obligation will have to be fixed in advance. In addition, such information has to be made available through an up-to-date online registry to be offered by the service provider.

The Regulation aims to ensure that customers' right to free choice of data service provider is not affected by barriers and difficulties arising from lack of interoperability. The regulation even contemplates an obligation of proactivity so that the change of provider takes place without incidents in the provision of the service to the customer, obliging them to adopt reasonable measures to ensure "functional equivalence" and even to offer free of charge open interfaces to facilitate this process. However, in some cases - in particular where two services are intended to be used in parallel - the former provider is allowed to pass on certain costs that may have been incurred.

Ultimately, the interoperability of data processing services goes beyond simple technical or semantic aspects, so that it becomes an unavoidable premise for ensuring the portability of digital assets, guaranteeing the security and integrity of services and, among other objectives, not interfering with the incorporation of technological innovations, all with a marked prominence of cloud services.

Smart contracts and interoperability

The Data Regulation also pays particular attention to the interoperability conditions allowing the automated execution of data exchanges, for which it is essential to set them in a predetermined way. Otherwise, the optimal operating conditions required by the digital environment, especially from the point of view of efficiency, would be affected.

The new regulation includes specific obligations for smart contract providers and also for those who deploy smart contract tools in the course of their commercial, business or professional activity. For this purpose, a smart contract is defined as a contract that

a computer programme used for the automated execution of an agreement or part thereof, which uses a sequence of electronic data records and ensures their completeness and the accuracy of their chronological order

They have to ensure that smart contracts comply with the obligations of the Regulation as regards the provision of data and, among other aspects, it will be essential to ensure "consistency with the terms of the data sharing agreement that executes the smart contract". They shall therefore be responsible for the effective fulfilment of these requirements by carrying out a conformity assessment and issuing a declaration of compliance with these requirements.

To facilitate the enforcement of these safeguards, the Regulation provides for a presumption of compliance where harmonised standards published in the Official Journal of the European Union are respected the Commission is authorised to request European standardisation organisations to draw up specific provisions.

In the last five years, and in particular since the 2020 Strategy, there has been significant progress in European regulation, which makes it possible to state that the right legal conditions are in place to ensure the availability of quality data to drive technological innovation. As far as interoperability is concerned, very important steps have already been taken, especially in the public sector public sector where we can find disruptive technologies that can be extremely useful. However, the challenge of precisely specifying the scope of the legally established obligations still remains.

For this reason, the Data Regulation itself empowers the Commission toadopt common specifications to ensure effective compliance with the measures it envisages if necessary. However, this is a subsidiary measure, as other avenues to achieve interoperability, such as the development of harmonised standards through standardisation organisations, must be pursued first.

In short, regulating interoperability requires an ambitious approach, as recognised by the Data Regulation itself, although it is a complex process that requires implementing measures at different levels that go beyond the simple adoption of legal rules, even if such legislation represents an important step forward to boost innovation under the right conditions, i.e. beyond simple technological premises.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The process of technological modernisation in the Administration of Justice in Spain began, to a large extent, in 2011. That year, the first regulation specifically aimed at promoting the use of information and communication technologies was approved. The aim of this regulation was to establish the conditions for recognising the validity of the use of electronic means in judicial proceedings and, above all, to provide legal certainty for procedural processing and acts of communication, including the filing of pleadings and the receipt of notifications of decisions. In this sense, the legislation established a basic legal status for those dealing with the administration of justice, especially for professionals. Likewise, the Internet presence of the Administration of Justice was given legal status, mainly with the appearance of electronic offices and access points, expressly admitting the possibility that the proceedings could be carried out in an automated manner.

However, as with the 2015 legal regulation of the common administrative procedure and the legal regime of the public sector, the management model it was inspired by was substantially oriented towards the generation, preservation and archiving of documents and records. Although a timid consideration of data was already apparent, it was largely too general in the scope of the regulation, as it was limited to recognising and ensuring security, interoperability and confidentiality.

In this context, the approval of Royal Decree-Law 6/2023 of 19 December has been a very important milestone in this process, as it incorporates important measures that aim to go beyond mere technological modernisation. Among other issues, it seeks to lay the foundations for an effective digital transformation in this area.

Towards a data-driven management orientation

Although this new regulatory framework largely consolidates and updates the previous regulation, it is an important step forward in facilitating the digital transformation as it establishes some essential premises without which it would be impossible to achieve this objective. Specifically, as stated in the Explanatory Memorandum:

From the understanding of the capital importance of data in a contemporary digital society, a clear and decisive commitment is made to its rational use in order to achieve evidence and certainty at the service of the planning and elaboration of strategies that contribute to a better and more effective public policy of Justice. [...] These data will not only benefit the Administration itself, but all citizens through the incorporation of the concept of "open data" in the Administration of Justice. This same data orientation will facilitate so-called automated, assisted and proactive actions.

In this sense, a general principle of data orientation is expressly recognised, thus overcoming the restrictions of a document- and file-based electronic management model as it has existed until now. This is intended not only to achieve objectives of improving procedural processing but also to facilitate its use for other purposes such as the development of dashboards, the generation of automated, assisted and proactive actions, the use of artificial intelligence systems and its publication in open data portals.

How has this principle been put into practice?

The main novelties of this regulatory framework from the perspective of the data orientation principle are the following:

- As a general rule, IT and communication systems shall allow for the exchange of information in structured data format, facilitating their automation and integration into the judicial file. To this end, the implementation of a data interoperability platform is envisaged, which will have to be compatible with the Data Intermediation Platform of the General State Administration.

- Data interoperability between judicial and prosecutorial bodies and data portals are set up as e-services of the administration of justice. The specific technical conditions for the provision of such services are to be defined through the State Technical Committee for e-Judicial Administration (CTEAJE).

- In order, among other objectives, to facilitate the promotion of artificial intelligence, the implementation of automated, assisted and proactive activities, as well as the publication of information in open data portals, a requirement is established for all information and communication systems to ensure that the management of information incorporate metadata and is based on common and interoperable data models. With regard to communications in particular, data orientation is also reflected in the electronic channels used for communications.

- In contrast to the common administrative procedure, the legal definition of court file incorporates an explicit reference to data as one of the basic units of the common administrative procedure.

- A specific regulation is included for the so-called Justice Administration Data Portal, so that the current data access tool in this area is legally enshrined for the first time. Specifically, in addition to establishing certain minimum contents and assigning competences to various bodies, it envisages the creation of a specific section on open data, as well as a mandate to the competent administrations to make them automatically processable and interoperable with the state open data portal. In this respect, the general regulations already existing for the rest of the public sector are declared applicable, without prejudice to the singularities that may be specifically contemplated in the procedural regulations.

In short, the new regulation is an important step in articulating the process of digital transformation of the Administration of Justice based on a data-driven management model. However, the unique competencies and organisational characteristics of this area require a unique governance model. For this reason, a specific institutional framework for cooperation has been envisaged, the effective functioning of which is essential for the implementation of the legal provisions and, ultimately, for addressing the challenges, difficulties and opportunities posed by open data and the re-use of public sector information in the judicial area. These are challenges that need to be tackled decisively so that the technological modernisation of the Justice Administration facilitates its effective digital transformation.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The European Union has placed the digital transformation of the public sector at the heart of its policy agenda. Through various initiatives under the Digital Decade policy programme, the EU aims to boost the efficiency of public services and provide a better experience for citizens. A goal for which the exchange of data and information in an agile manner between institutions and countries is essential.

This is where interoperability and the search for new solutions to promote it becomes important. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) offer great opportunities in this field, thanks to their ability to analyse and process huge amounts of data.

A report to analyse the state of play

Against this background, the European Commission has published an extensive and comprehensive report entitled "Artificial Intelligence for Interoperability in the European Public Sector", which provides an analysis of how AI is already improving interoperability in the European public sector. The report is divided into three parts:

- A literature and policy review on the synergies between IA and interoperability. It highlights the legislative work carried out by the EU. It highlights the Interoperable Europe Act which seeks to establish a governance structure and to foster an ecosystem of reusable and interoperable solutions for public administration. Mention is also made of the Artificial Intelligence Act, designed to ensure that AI systems used in the EU are safe, transparent, traceable, non-discriminatory and environmentally friendly.

- The report continues with a quantitative analysis of 189 use cases. These cases were selected on the basis of the inventory carried out in the report "AI Watch. European overview of the use of Artificial Intelligence by the public sector" which includes 686 examples, recently updated to 720.

- A qualitative study that elaborates on some of the above cases. Specifically, seven use cases have been characterised (two of them Spanish), with an exploratory objective. In other words, it seeks to extract knowledge about the challenges of interoperability and how AI-based solutions can help.

Conclusions of the study

AI is becoming an essential tool for structuring, preserving, standardising and processing public administration data, improving interoperability within and outside public administration. This is a task that many organisations are already doing.

Of all the AI use cases in the public sector analysed in the study, 26% were related to interoperability. These tools are used to improve interoperability by operating at different levels: technical, semantic, legal and organisational. The same AI system can operate at different layers.

- The semantic layer of interoperability is the most relevant (91% of cases). The use of ontologies and taxonomies to create a common language, combined with AI, can help establish semantic interoperability between different systems. One example is the EPISA60 project, which is based on natural language processing, using entity recognition and machine learning to explore digital documents.

- In second place is the organisational layer, with 35% of cases. It highlights the use of AI for policy harmonisation, governance models and mutual data recognition, among others. In this regard, the Austrian Ministry of Justice launched the JustizOnline project which integrates various systems and processes related to the delivery of justice.

- The 33% of the cases focused on the legal layer. In this case, the aim is to ensure that the exchange of data takes place in compliance with legal requirements on data protection and privacy. The European Commission is preparing a study to explore how AI can be used to verify the transposition of EU legislation by Member States. For this purpose, different articles of the laws are compared with the help of an AI.

- Lastly, there is the technical layer, with 21% of cases. In this field, AI can help the exchange of data in a seamless and secure way. One example is the work carried out at the Belgian research centre VITO, based on AI data encoding/decoding and transport techniques.

Specifically, the three most common actions that AI-based systems take to drive data interoperability are: detecting information (42%), structuring it (22%) and classifying it (16%). The following table, extracted from the report, shows all the detailed activities:

Download here the accessible version of the table

The report also analyses the use of AI in specific areas. Its use in "general public services" stands out (41%), followed by "public order and security" (17%) and "economic affairs" (16%). In terms of benefits, administrative simplification stands out (59%), followed by the evaluation of effectiveness and efficiency (35%) and the preservation of information (27%).

AI use cases in Spain

The third part of the report looks in detail at concrete use cases of AI-based solutions that have helped to improve public sector interoperability. Of the seven solutions characterised, two are from Spain:

- Energy vulnerability - automated assessment of the fuel poverty report. When energy service providers detect non-payments, they must consult with the municipality to determine whether the user is in a situation of social vulnerability before cutting off the service, in which case supplies cannot be cut off. Municipalities receive monthly listings from companies in different formats and have to go through a costly manual bureaucratic process to validate whether a citizen is at social or economic risk. To solve this challenge, the Administració Oberta de Catalunya (AOC) has developed a tool that automates the data verification process, improving interoperability between companies, municipalities and other administrations.

- Automated transcripts to speed up court proceedings. In the Basque Country, trial transcripts by the administration are made by manually reviewing the videos of all sessions. Therefore, it is not possible to easily search for words, phrases, etc. This solution converts voice data into text automatically, which allows you to search and save time.

Recommendations

The report concludes with a series of recommendations on what public administrations should do:

- Raise internal awareness of the possibilities of AI to improve interoperability. Through experimentation, they will be able to discover the benefits and potential of this technology.

- Approach the adoption of an AI solution as a complex project with not only technical, but also organisational, legal, ethical, etc. implications.

- Create optimal conditions for effective collaboration between public agencies. This requires a common understanding of the challenges to be addressed in order to facilitate data exchange and the integration of different systems and services.

- Promote the use of uniform and standardised ontologies and taxonomies to create a common language and shared understanding of data to help establish semantic interoperability between systems.

- Evaluate current legislation, both in the early stages of experimentation and during the implementation of an AI solution, on a regular basis. Collaboration with external actors to assess the adequacy of the legal framework should also be considered. In this regard, the report also includes recommendations for the next EU policy updates.

- Support the upgrading of the skills of AI and interoperability specialists within the public administration. Critical tasks of monitoring AI systems are to be kept within the organisation.

Interoperability is one of the key drivers of digital government, as it enables the seamless exchange of data and processes, fostering effective collaboration. AI can help automate tasks and processes, reduce costs and improve efficiency. It is therefore advisable to encourage their adoption by public bodies at all levels.

What challenges do data publishers face?

In today's digital age, information is a strategic asset that drives innovation, transparency and collaboration in all sectors of society. This is why data publishing initiatives have developed enormously as a key mechanism for unlocking the potential of this data, allowing governments, organisations and citizens to access, use and share it.

However, there are still many challenges for both data publishers and data consumers. Aspects such as the maintenance of APIs(Application Programming Interfaces) that allow us to access and consume published datasets or the correct replication and synchronisation of changing datasets remain very relevant challenges for these actors.

In this post, we will explore how Linked Data Event Streams (LDES), a new data publishing mechanism, can help us solve these challenges. what exactly is LDES? how does it differ from traditional data publication practices? And, most importantly, how can you help publishers and consumers of data to facilitate the use of available datasets?

Distilling the key aspects of LDES

When Ghent University started working on a new mechanism for the publication of open data, the question they wanted to answer was: How can we make open data available to the public? What is the best possible API we can design to expose open datasets?

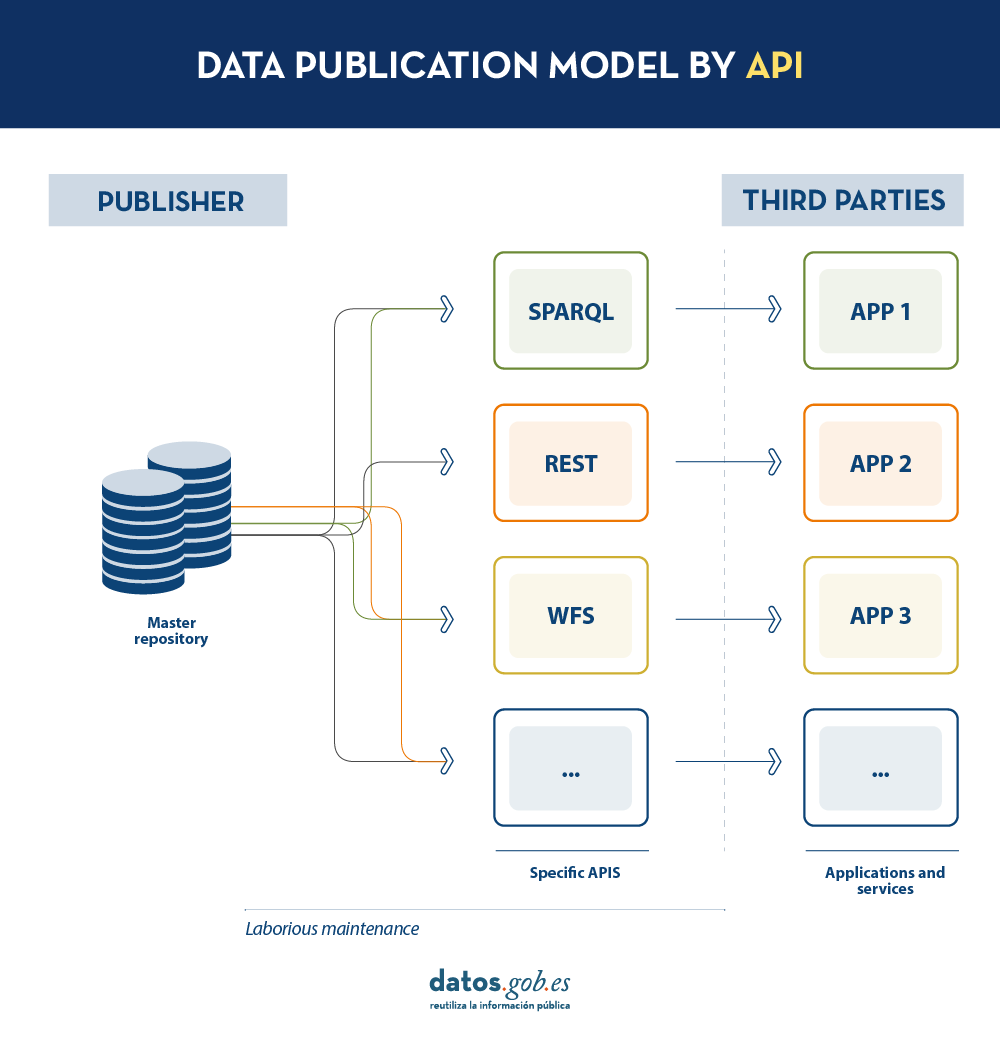

Today, data publishers use multiple mechanisms to publish their different datasets. On the one hand, it is easy to find APIs. These include SPARQL, a standard for querying linked data(Link Data), but also REST or WFS, for accessing datasets with a geospatial component. On the other hand, it is very common that we find the possibility to access data dumps in different formats (i.e. CSV, JSON, XLS, etc.) that we can download for use.

In the case of data dumps, it is very easy to encounter synchronisation problems. This occurs when, after a first dump, a change occurs that requires modification of the original dataset, such as changing the name of a street in a previously downloaded street map. Given this change, if the third party chooses to modify the street name on the initial dump instead of waiting for the publisher to update its data in the master repository to perform a new dump, the data handled by the third party will be out of sync with the data handled by the publisher. Similarly, if it is the publisher that updates its master repository but these changes are not downloaded by the third party, both will handle different versions of the dataset.

On the other hand, if the publisher provides access to data through query APIs, rather than through data dumps to third parties, synchronisation problems are solved, but building and maintaining a high and varied volume of query APIs is a major effort for data publishers.

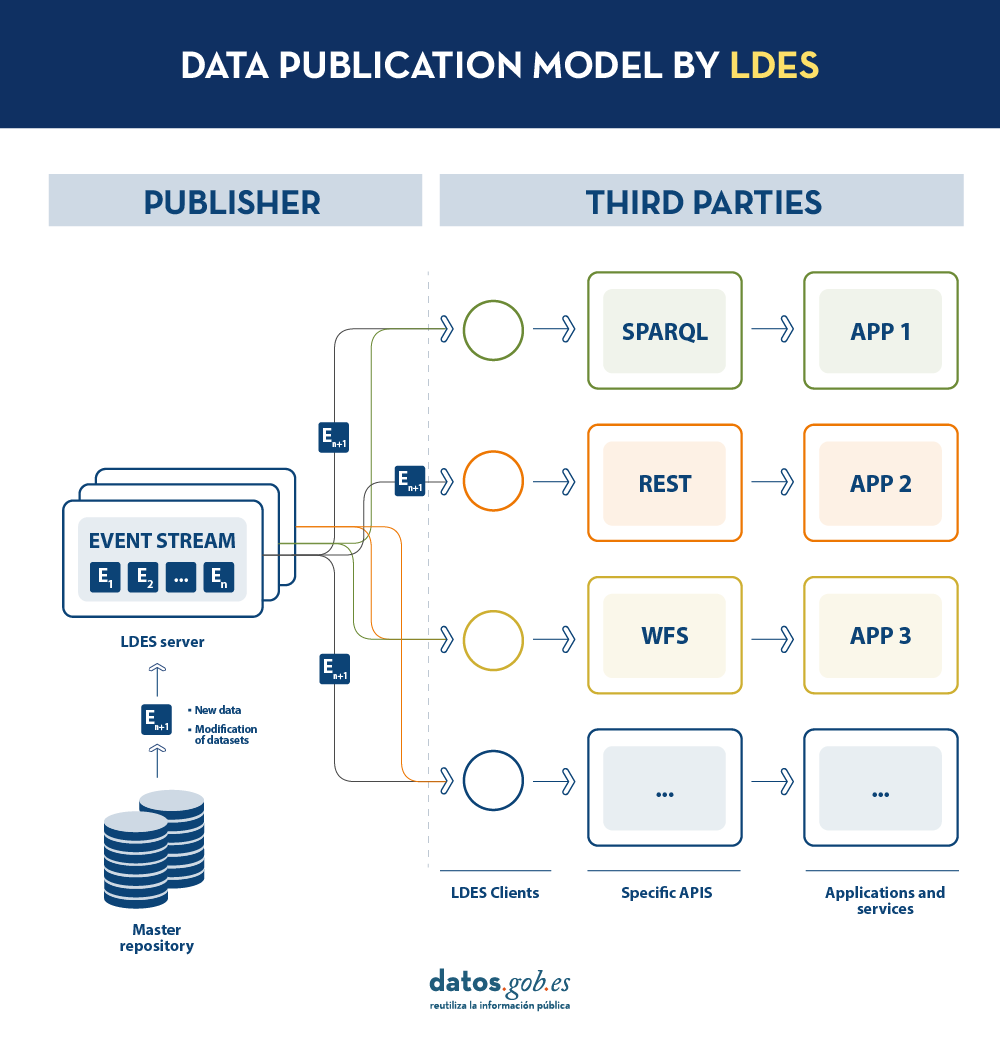

LDES seeks to solve these different problems by applying the concept of Linked Data to an event stream . According to the definition in its own specification, a Linked Data Event Stream (LDES) is a collection of immutable objects where each object is described in RDF terns.

Firstly, the fact that the LDES are committed to Linked Data provides design principles that allow combining diverse data and/or data from different sources, as well as their consultation through semantic mechanisms that allow readability by both humans and machines. In short, it provides interoperability and consistency between datasets, thus facilitating search and discovery.

On the other hand, the event streams or data streams, allow consumers to replicate the history of datasets, as well as synchronise recent changes. Any new record added to a dataset, or any modification of existing records (in short, any change), is recorded as a new incremental event in the LDES that will not alter previous events. Therefore, data can be published and consumed as a sequence of events, which is useful for frequently changing data, such as real-time information or information that undergoes constant updates, as it allows synchronisation of the latest updates without the need for a complete re-download of the entire master repository after each modification.

In such a model, the publisher will only need to develop and maintain one API, the LDES, rather than multiple APIs such as WFS, REST or SPARQL. Different third parties wishing to use the published data will connect (each third party will implement its LDES client) and receive the events of the streams to which they have subscribed. Each third party will create from the information collected the specific APIs it deems appropriate based on the type of applications they want to develop or promote. In short, the publisher will not have to solve all the potential needs of each third party in the publication of data, but by providing an LDES interface (minimum base API), each third party will focus on its own problems.

In addition, to facilitate access to large volumes of data or to data that may be distributed across different sources, such as an inventory of electric charging points in Europe, LDES provides the ability to fragment datasets. Through the TREE specification, LDES allows different types of relationships between data fragments to be established. This specification allows publishing collections of entities, called members, and provides the ability to generate one or more representations of these collections. These representations are organised as views, distributing the members through pages or nodes interconnected by relationships. Thus, if we want the data to be searchable through temporal indexes, it is possible to set a temporal fragmentation and access only the pages of a temporal interval. Similarly, alphabetical or geospatial indexes can be provided and a consumer can access only the data needed without the need to 'dump' the entire dataset.

What conclusions can we draw from LDES?

In this post we have looked at the potential of LDES as a mechanism for publishing data. Some of the most relevant learnings are:

- LDES aims to facilitate the publication of data through minimal base APIs that serve as a connection point for any third party wishing to query or build applications and services on top of datasets.

- The construction of an LDES server, however, has a certain level of technical complexity when it comes to establishing the necessary architecture for the handling of published data streams and their proper consultation by data consumers.

- The LDES design allows the management of both high rate of change data (i.e. data from sensors) and low rate of change data (i.e. data from a street map). Both scenarios can handle any modification of the dataset as a data stream.

- LDES efficiently solves the management of historical records, versions and fragments of datasets. This is based on the TREE specification, which allows different types of fragmentation to be established on the same dataset.

Would you like to know more?

Here are some references that have been used to write this post and may be useful to the reader who wishes to delve deeper into the world of LDES:

- Linked Data Event Streams: the core API for publishing base registries and sensor data, Pieter Colpaert. ENDORSE, 2021. https://youtu.be/89UVTahjCvo?si=Yk_Lfs5zt2dxe6Ve&t=1085

- Webinar on LDES and Base registries. Interoperable Europe, 17 January 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wOeISYms4F0&ab_channel=InteroperableEurope

- SEMIC Webinar on the LDES specification. Interoperable Europe, 21 April 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jjIq63ZdDAI&ab_channel=InteroperableEurope

- Linked Data Event Streams (LDES). SEMIC Support Centre. https://joinup.ec.europa.eu/collection/semic-support-centre/linked-data-event-streams-ldes

- Publishing data with Linked Data Event Streams: why and how. EU Academy. https://academy.europa.eu/courses/publishing-data-with-linked-data-event-streams-why-and-how

Content prepared by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies linked to the data economy. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The European Union aims to boost the Data Economy by promoting the free flow of data between member states and between strategic sectors, for the benefit of businesses, researchers, public administrations and citizens. Undoubtedly, data is a critical factor in the industrial and technological revolution we are experiencing, and therefore one of the EU's digital priorities is to capitalise on its latent value, relying on a single market where data can be shared under conditions of security and, above all, sovereignty, as this is the only way to guarantee indisputable European values and rights.

Thus, the European Data Strategy seeks to enhance the exchange of data on a large scale, under distributed and federated environments, while ensuring cybersecurity and transparency. To achieve scale, and to unlock the full potential of data in the digital economy, a key element is building trust. This, as a basic element that conditions the liquidity of the ecosystem, must be developed coherently across different areas and among different actors (data providers, users, intermediaries, service platforms, developers, etc.). Therefore, their articulation affects different perspectives, including business and functional, legal and regulatory, operational, and even technological. Therefore, success in these highly complex projects depends on developing strategies that seek to minimise barriers to entry for participants, and maximise the efficiency and sustainability of the services offered. This in turn translates into the development of data infrastructures and governance models that are easily scalable, and that provide the basis for effective data exchange to generate value for all stakeholders.

A methodology to boost data spaces

Spain has taken on the task of putting this European strategy into practice, and has been working for years to create an environment conducive to facilitating the deployment and establishment of a Sovereign Data Economy, supported, among other instruments, by the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan. In this sense, and from its coordinating and enabling role, the Data Office has made efforts to design a general conceptual methodology , agnostic to a specific sector. It shapes the creation of data ecosystems around practical projects that bring value to the members of the ecosystem.

Therefore, the methodology consists of several elements, one of them being experimentation. This is because, by their flexible nature, data can be processed, modelled and thus interpreted from different perspectives. For this reason, experimentation is key to properly calibrate those processes and treatments needed to reach the market with pilots or business cases already close to the industries, so that they are closer to generating a positive impact. In this sense, it is necessary to demonstrate tangible value and underpin its sustainability, which implies, as a minimum, having:

- Frameworks for effective data governance

- Actions to improve the availability and quality of data, also seeking to increase their interoperability by design

- Tools and platforms for data exchange and exploitation.

Furthermore, given that each sector has its own specificity in terms of data types and semantics, business models, and participants' needs, the creation of communities of experts, representing the voice of the market, is another key element in generating useful projects. Based on this active listening, which leads to an understanding of the dynamics of data in each sector, it is possible to characterise the market and governance conditions necessary for the deployment of data spaces in strategic sectors such as tourism, mobility, agri-food, commerce, health and industry.

In this process of community building, data co-operatives play a fundamental role, as well as the more general figure of the data broker, which serves to raise awareness of the existing opportunity and favour the effective creation and consolidation of these new business models.

All these elements are different pieces of a puzzle with which to explore new business development opportunities, as well as to design tangible projects to demonstrate the differential value that data sharing will bring to the reality of industries. Thus, from an operational perspective, the last element of the methodology is the development of concrete use cases. These will also allow the iterative deployment of a catalogue of reusable experience and data resources in each sector to facilitate the construction of new projects. This catalogue thus becomes the centrepiece of a common sectoral and federated platform, whose distributed architecture also facilitates cross-sectoral interconnection.

On the shoulders of giants

It should be noted that Spain is not starting from scratch, as it already has a powerful ecosystem of innovation and experimentation in data, offering advanced services. We therefore believe it would be interesting to make progress in the harmonisation or complementarity of their objectives, as well as in the dissemination of their capacities in order to gain capillarity. Furthermore, the proposed methodology reinforces the alignment with European projects in the same field, which will serve to connect learning and progress from the national level to those made at EU level, as well as to put into practice the design tasks of the "cyanotypes" promulgated by the European Commission through the Data Spaces Support Centre.

Finally,the promotion of experimental or pilot projects also enables the development of standards for innovative data technologies, which is closely related to the Gaia-X project. Thus, the Gaia-X Hub Spain has an interoperability node, which serves to certify compliance with the rules prescribed by each sector, and thus to generate the aforementioned digital trust based on their specific needs.

At the Data Office, we believe that the interconnection and future scalability of data projects are at the heart of the effort to implement the European Data Strategy, and are crucial to achieve a dynamic and rich Data Economy, but at the same time a guarantor of European values and where traceability and transparency help to collectivise the value of data, catalysing a stronger and more cohesive economy.

Cloud data storage is currently one of the fastest growing segments of enterprise software, which is facilitating the incorporation of a large number of new users into the field of analytics.

As we introduced in a previous post, a new format, Parquet, has among its goals to empower and advance analytics for this rapidly growing community and facilitate interoperability between various cloud data stores and compute engines.

Parquet is described by its own creator, Apache, as: "An open source data file format designed for efficient data storage and retrieval. It provides enhanced performance for handling complex data on a massive scale."

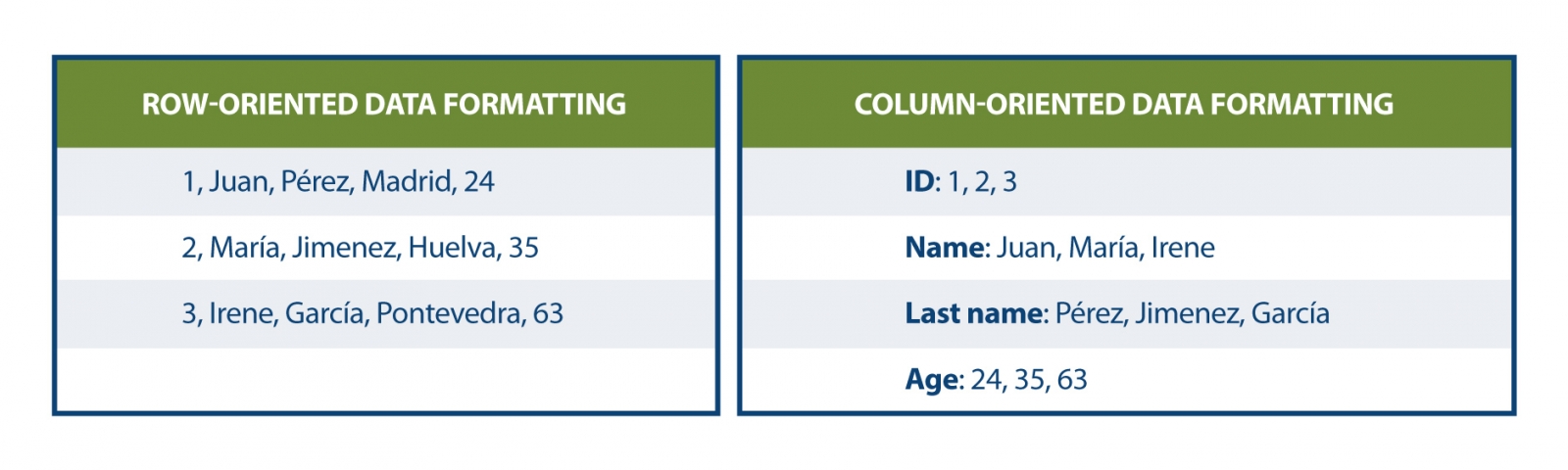

Parquet is defined as a column-oriented data format that is intended as a modern alternative to CSV files. Unlike row-based formats such as CSV, Parquet stores data on a columnar basis, which means that the values of each column in the table are stored contiguously, rather than the values of each record, as shown below:

This storage method has advantages in terms of compact storage and fast queries compared to classical formats. Parquet works effectively on denormalized datasets containing many columns and allows querying these data faster and more efficiently.

This storage method has advantages in terms of compact storage and fast queries compared to classical formats. Parquet works effectively on denormalized datasets containing many columns and allows querying these data faster and more efficiently.

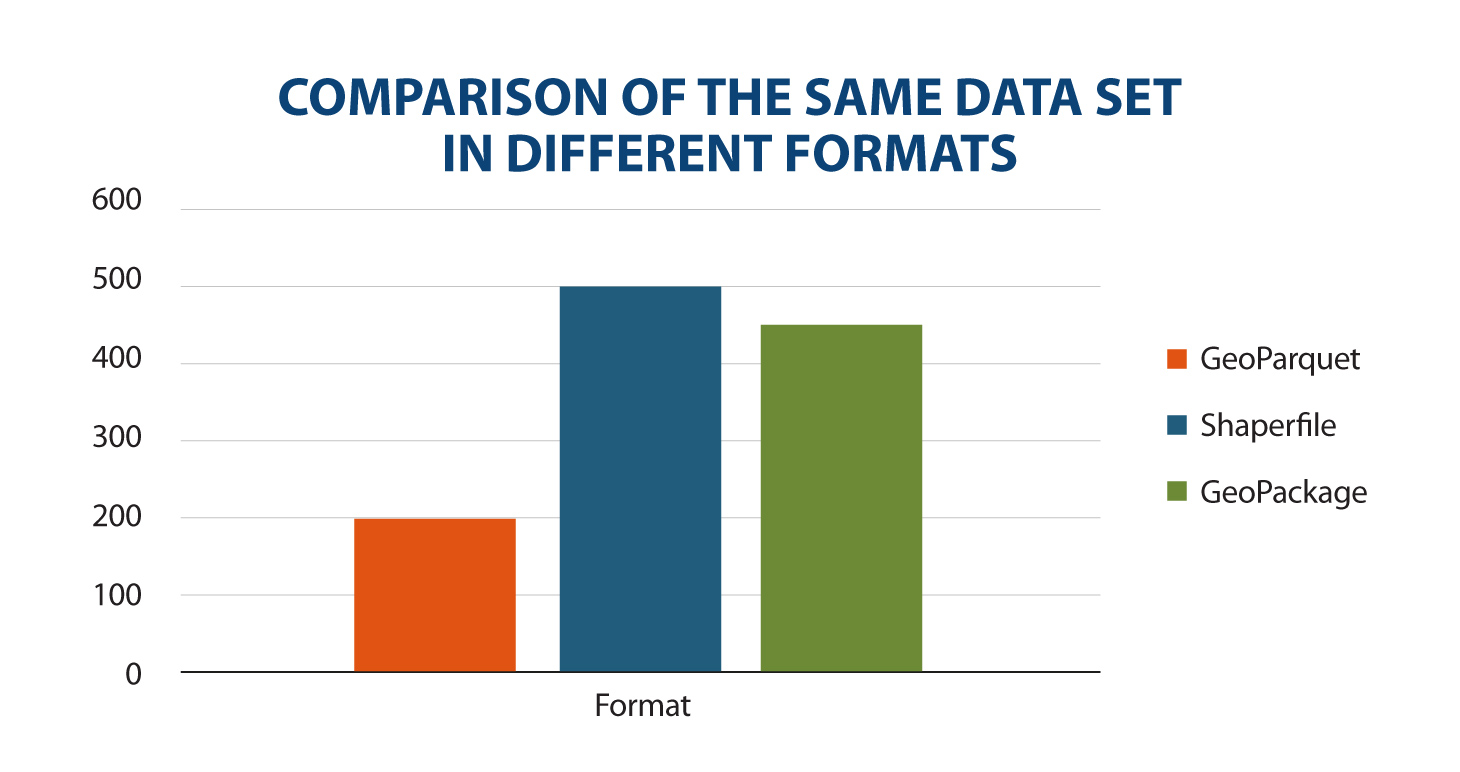

A new format for spatial data was released in August 2023: GeoParquet 1.0.0. During that same month, the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) reported the formation of a new GeoParquet Standards Working Group, which aims to promote the adoption of this format as an OGC encoding standard for cloud-native vector data.

GeoParquet 1.0.0.0 corrects some shortcomings of Parquet, which did not offer good spatial data support. Similarly, interoperability in cloud environments was complex for geospatial data, because in the absence of a standard or guidelines on how to store geographic data, it was interpreted differently by each system. This led to two significant results:

· Data providers could not share their data in a unified format. If they wanted to enable users in different systems, they had to support the different variations of spatial support in the different engines.

· It was not possible to export spatial data from one system and import it into another without significant processing between them.

Estas deficiencias han sido solventadas con GeoParquet que, además agrega tipos geoespaciales al formato Parquet, al mismo tiempo que establece una serie de estándares para varios aspectos claves en la representación de datos espaciales:

· Columns containing spatial data: it is allowed to have multiple columns containing spatial data (Point, Line and Polygon), with the designation of one column as "main".

· Geometry/geography encoding: defines how geometry or geography information is encoded. Initially a well-known binary encoding and Well-known text (WKT) is used, but work is underway to implement GeoArrow as a new form of encoding.

- Spatial reference system: specifies in which spatial reference system the data is located. The specification is compatible with several alternative coordinate reference systems.

- Coordinate type: defines whether the coordinates are planar or spherical, providing information on the geometry and nature of the coordinates used.

In addition, GeoParquet includes metadata at two levels: