Open data portals help municipalities to offer structured and transparent access to the data they generate in the exercise of their functions and in the provision of the services they are responsible for, while also fostering the creation of applications, services and solutions that generate value for citizens, businesses and public administrations themselves.

The report aims to provide a practical guide for municipal administrations to design, develop and maintain effective open data portals, integrating them into the overall smart city strategy. The document is structured in several sections ranging from strategic planning to technical and operational recommendations necessary for the creation and maintenance of open data portals. Some of the main keys are:

Fundamental principles

The report highlights the importance of integrating open data portals into municipal strategic plans, aligning portal objectives with local priorities and citizens' expectations. It also recommends drawing up a Plan of measures for the promotion of openness and re-use of data (RISP Plan in Spanish acronyms), including governance models, clear licences, an open data agenda and actions to stimulate re-use of data. Finally, it emphasises the need for trained staff in strategic, technical and functional areas, capable of managing, maintaining and promoting the reuse of open data.

General requirements

In terms of general requirements to ensure the success of the portal, the importance of offering quality data, consistent and updated in open formats such as CSV and JSON, but also in XLS, favouring interoperability with national and international platforms through open standards such as DCAT-AP, and guaranteeing effective accessibility of the portal through an intuitive and inclusive design, adapted to different devices. It also points out the obligation to strictly comply with privacy and data protection regulations, especially the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

To promote re-use, the report advises fostering dynamic ecosystems through community events such as hackathons and workshops, highlighting successful examples of practical application of open data. Furthermore, it insists on the need to provide useful tools such as APIs for dynamic queries, interactive data visualisations and full documentation, as well as to implement sustainable funding and maintenance mechanisms.

Technical and functional guidelines

Regarding technical and functional guidelines, the document details the importance of building a robust and scalable technical infrastructure based on cloud technologies, using diverse storage systems such as relational databases, NoSQL and specific solutions for time series or geospatial data. It also highlights the importance of integrating advanced automation tools to ensure consistent data quality and recommends specific solutions to manage real-time data from the Internet of Things (IoT).

In relation to the usability and structure of the portal, the importance of a user-centred design is emphasised, with clear navigation and a powerful search engine to facilitate quick access to data. Furthermore, it stresses the importance of complying with international accessibility standards and providing tools that simplify interaction with data, including clear graphical displays and efficient technical support mechanisms.

The report also highlights the key role of APIs as fundamental tools to facilitate automated and dynamic access to portal data, offering granular queries, clear documentation, robust security mechanisms and reusable standard formats. It also suggests a variety of tools and technical frameworks to implement these APIs efficiently.

Another critical aspect highlighted in the document is the identification and prioritisation of datasets for publication, as the progressive planning of data openness allows adjusting technical and organisational processes in an agile way, starting with the data of greatest strategic relevance and citizen demand.

Finally, the guide recommends establishing a system of metrics and indicators according to the UNE 178301:2015 standard to assess the degree of maturity and the real impact of open data portals. These metrics span strategic, legal, organisational, technical, economic and social domains, providing a holistic approach to measure both the effectiveness of data publication and its tangible impact on society and the local economy.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the report provides a strategic, technical and practical framework that serves as a reference for the deployment of municipal open data portals for cities to maximise their potential as drivers of economic and social development. In addition, the integration of artificial intelligence at various points in open data portal projects represents a strategic opportunity to expand their capabilities and generate a greater impact on citizens.

You can read the full report here.

The concept of data commons emerges as a transformative approach to the management and sharing of data that serves collective purposes and as an alternative to the growing number of macrosilos of data for private use. By treating data as a shared resource, data commons facilitate collaboration, innovation and equitable access to data, emphasising the communal value of data above all other considerations. As we navigate the complexities of the digital age - currently marked by rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and the continuing debate about the challenges in data governance- the role that data commons can play is now probably more important than ever.

What are data commons?

The data commons refers to a cooperative framework where data is collected, governed and shared among all community participants through protocols that promote openness, equity, ethical use and sustainability. The data commons differ from traditional data-sharing models mainly in the priority given to collaboration and inclusion over unitary control.

Another common goal of the data commons is the creation of collective knowledge that can be used by anyone for the good of society. This makes them particularly useful in addressing today's major challenges, such as environmental challenges, multilingual interaction, mobility, humanitarian catastrophes, preservation of knowledge or new challenges in health and health care.

In addition, it is also increasingly common for these data sharing initiatives to incorporate all kinds of tools to facilitate data analysis and interpretation , thus democratising not only the ownership of and access to data, but also its use.

For all these reasons, data commons could be considered today as a criticalpublic digital infrastructure for harnessing data and promoting social welfare.

Principles of the data commons

The data commons are built on a number of simple principles that will be key to their proper governance:

- Openness and accessibility: data must be accessible to all authorised persons.

- Ethical governance: balance between inclusion and privacy.

- Sustainability: establish mechanisms for funding and resources to maintain data as a commons over time.

- Collaboration: encourage participants to contribute new data and ideas that enable their use for mutual benefit.

- Trust: relationships based on transparency and credibility between stakeholders.

In addition, if we also want to ensure that the data commons fulfil their role as public domain digital infrastructure, we must guarantee other additional minimum requirements such as: existence of permanent unique identifiers , documented metadata , easy access through application programming interfaces (APIs), portability of the data, data sharing agreements between peers and ability to perform operations on the data.

The important role of the data commons in the age of Artificial Intelligence

AI-driven innovation has exponentially increased the demand for high-quality, diverse data sets a relatively scarce commodityat a large scale that may lead to bottlenecks in the future development of the technology and, at the same time, makes data commons a very relevant enabler for a more equitable AI. By providing shared datasets governed by ethical principles, data commons help mitigate common risks such as risks, data monopolies and unequal access to the benefits of AI.

Moreover, the current concentration of AI developments also represents a challenge for the public interest. In this context, the data commons hold the key to enable a set of alternative, public and general interest-oriented AI systems and applications, which can contribute to rebalancing this current concentration of power. The aim of these models would be to demonstrate how more democratic, public interest-oriented and purposeful systems can be designed based on public AI governance principles and models.

However, the era of generative AI also presents new challenges for data commons such as, for example and perhaps most prominently, the potential risk of uncontrolled exploitation of shared datasets that could give rise to new ethical challenges due to data misuse and privacy violations.

On the other hand, the lack of transparency regarding the use of the data commons by the AI could also end up demotivating the communities that manage them, putting their continuity at risk. This is due to concerns that in the end their contribution may be benefiting mainly the large technology platforms, without any guarantee of a fairer sharing of the value and impact generated as originally intended".

For all of the above, organisations such as Open Future have been advocating for several years now for Artificial Intelligence to function as a common good, managed and developed as a digital public infrastructure for the benefit of all, avoiding the concentration of power and promoting equity and transparency in both its development and its application.

To this end, they propose a set of principles to guide the governance of the data commons in its application for AI training so as to maximise the value generated for society and minimise the possibilities of potential abuse by commercial interests:

- Share as much data as possible, while maintaining such restrictions as may be necessary to preserve individual and collective rights.

- Be fully transparent and provide all existing documentation on the data, as well as on its use, and clearly distinguish between real and synthetic data.

- Respect decisions made about the use of data by persons who have previously contributed to the creation of the data, either through the transfer of their own data or through the development of new content, including respect for any existing legal framework.

- Protect the common benefit in the use of data and a sustainable use of data in order to ensure proper governance over time, always recognising its relational and collective nature.

- Ensuring the quality of data, which is critical to preserving its value as a common good, especially given the potential risks of contamination associated with its use by AI.

- Establish trusted institutions that are responsible for data governance and facilitate participation by the entire data community, thus going a step beyond the existing models for data intermediaries.

Use cases and applications

There are currently many real-world examples that help illustrate the transformative potential of data commons:

- Health data commons : projects such as the National Institutes of Health's initiative in the United States - NIH Common Fund to analyse and share large biomedical datasets, or the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Research Data Commons , demonstrate how data commons can contribute to the acceleration of health research and innovation.

- AI training and machine learning: the evaluation of AI systems depends on rigorous and standardised test data sets. Initiatives such as OpenML or MLCommons build open, large-scale and diverse datasets, helping the wider community to deliver more accurate and secure AI systems.

- Urban and mobility data commons : cities that take advantage of shared urban data platforms improve decision-making and public services through collective data analysis, as is the case of Barcelona Dades, which in addition to a large repository of open data integrates and disseminates data and analysis on the demographic, economic, social and political evolution of the city. Other initiatives such as OpenStreetMaps itself can also contribute to providing freely accessible geographic data.

- Culture and knowledge preservation: with such relevant initiatives in this field as Mozilla's Common Voice project to preserve and revitalise the world's languages, or Wikidata, which aims to provide structured access to all data from Wikimedia projects, including the popular Wikipedia.

Challenges in the data commons

Despite their promise and potential as a transformative tool for new challenges in the digital age, the data commons also face their own challenges:

- Complexity in governance: Striking the right balance between inclusion, control and privacy can be a delicate task.

- Sustainability: Many of the existing data commons are fighting an ongoing battle to try to secure the funding and resources they need to sustain themselves and ensure their long-term survival.

- Legal and ethical issues: addressing challenges relating to intellectual property rights, data ownership and ethical use remain critical issues that have yet to be fully resolved.

- Interoperability: Ensuring compatibility between datasets and platforms is a persistent technical hurdle in almost any data sharing initiative, and the data commons were to be no exception.

The way forward

To unlock their full potential, the data commons require collective action and a determined commitment to innovation. Key actions include:

- Develop standardised governance models that strike a balance between ethical considerations and technical requirements.

- Apply the principle of reciprocity in the use of data, requiring those who benefit from it to share their results back with the community.

- Protection of sensitive data through anonymisation, preventing data from being used for mass surveillance or discrimination.

- Encourage investment in infrastructure to support scalable and sustainable data exchange.

- Promote awareness of the social benefits of data commons to encourage participation and collaboration.

Policy makers, researchers and civil society organisations should work together to create an ecosystem in which the data commons can thrive, fostering more equitable growth in the digital economy and ensuring that the data commons can benefit all.

Conclusion

The data commons can be a powerful tool for democratising access to data and fostering innovation. In this era defined by AI and digital transformation, they offer us an alternative path to equitable, sustainable and inclusive progress. Addressing its challenges and adopting a collaborative governance approach through cooperation between communities, researchers and regulators will ensure fair and responsible use of data.

This will ensure that data commons become a fundamental pillar of the digital future, including new applications of Artificial Intelligence, and could also serve as a key enabling tool for some of the key actions that are part of the recently announced European competitiveness compass, such as the new Data Union strategy and the AI Gigafactories initiative.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation. The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a futuristic concept and has become a key tool in our daily lives. From movie or series recommendations on streaming platforms to virtual assistants like Alexa or Google Assistant on our devices, AI is everywhere. But how do you build an AI model? Despite what it might seem, the process is less intimidating if we break it down into clear and understandable steps.

Step 1: Define the problem

Before we start, we need to be very clear about what we want to solve. AI is not a magic wand: different models will work better in different applications and contexts so it is important to define the specific task we want to execute. For example, do we want to predict the sales of a product? Classify emails as spam or non-spam? Having a clear definition of the problem will help us structure the rest of the process.

In addition, we need to consider what kind of data we have and what the expectations are. This includes determining the desired level of accuracy and the constraints of available time or resources.

Step 2: Collect the data

The quality of an AI model depends directly on the quality of the data used to train it. This step consists of collecting and organising the data relevant to our problem. For example, if we want to predict sales, we will need historical data such as prices, promotions or buying patterns.

Data collection starts with identifying relevant sources, which can be internal databases, sensors, surveys... In addition to the company's own data, there is a wide ecosystem of data, both open and proprietary, that can be drawn upon to build more powerful models. For example, the Government of Spain makes available through the datos.gob.es portal multiple sets of open data published by public institutions. On the other hand, Amazon Web Services (AWS) through its AWS Data Exchange portal allows access and subscription to thousands of proprietary datasets published and maintained by different companies and organisations.

The amount of data required must also be considered here. AI models often require large volumes of information to learn effectively. It is also crucial that the data are representative and do not contain biases that could affect the results. For example, if we train a model to predict consumption patterns and only use data from a limited group of people, it is likely that the predictions will not be valid for other groups with different behaviours.

Step 3: Prepare and explore the data

Once the data have been collected, it is time to clean and normalise them. In many cases, raw data may contain problems such as errors, duplications, missing values, inconsistencies or non-standardised formats. For example, you might find empty cells in a sales dataset or dates that do not follow a consistent format. Before feeding the model with this data, it is essential to fit it to ensure that the analysis is accurate and reliable. This step not only improves the quality of the results, but also ensures that the model can correctly interpret the information.

Once the data is clean, it is essential to perform feature engineering (feature engineering), a creative process that can make the difference between a basic model and an excellent one. This phase consists of creating new variables that better capture the nature of the problem we want to solve. For example, if we are analysing onlinesales, in addition to using the direct price of the product, we could create new characteristics such as the price/category_average ratio, the days since the last promotion, or variables that capture the seasonality of sales. Experience shows that well-designed features are often more important for the success of the model than the choice of the algorithm itself.

In this phase, we will also carry out a first exploratory analysis of the data, seeking to familiarise ourselves with the data and detect possible patterns, trends or irregularities that may influence the model. Further details on how to conduct an exploratory data analysis can be found in this guide .

Another typical activity at this stage is to divide the data into training, validation and test sets. For example, if we have 10,000 records, we could use 70% for training, 20% for validation and 10% for testing. This allows the model to learn without overfitting to a specific data set.

To ensure that our evaluation is robust, especially when working with limited datasets, it is advisable to implement cross-validationtechniques. This methodology divides the data into multiple subsets and performs several iterations of training and validation. For example, in a 5-fold cross-validation, we split the data into 5 parts and train 5 times, each time using a different part as the validation set. This gives us a more reliable estimate of the real performance of the model and helps us to detect problems of over-fitting or variability in the results.

Step 4: Select a model

There are multiple types of AI models, and the choice depends on the problem we want to solve. Common examples are regression, decision tree models, clustering models, time series models or neural networks. In general, there are supervised models, unsupervised models and reinforcement learning models. More detail can be found in this post on how machines learn.

When selecting a model, it is important to consider factors such as the nature of the data, the complexity of the problem and the ultimate goal. For example, a simple model such as linear regression may be sufficient for simple, well-structured problems, while neural networks or advanced models might be needed for tasks such as image recognition or natural language processing. In addition, the balance between accuracy, training time and computational resources must also be considered. A more accurate model generally requires more complex configurations, such as more data, deeper neural networks or optimised parameters. Increasing the complexity of the model or working with large datasets can significantly lengthen the time needed to train the model. This can be a problem in environments where decisions must be made quickly or resources are limited and require specialised hardware, such as GPUs or TPUs, and larger amounts of memory and storage.

Today, many open source libraries facilitate the implementation of these models, such as TensorFlow, PyTorch or scikit-learn.

Step 5: Train the model

Training is at the heart of the process. During this stage, we feed the model with training data so that it learns to perform its task. This is achieved by adjusting the parameters of the model to minimise the error between its predictions and the actual results.

Here it is key to constantly evaluate the performance of the model with the validation set and make adjustments if necessary. For example, in a neural network-type model we could test different hyperparameter settings such as learning rate, number of hidden layers and neurons, batch size, number of epochs, or activation function, among others.

Step 6: Evaluate the model

Once trained, it is time to test the model using the test data set we set aside during the training phase. This step is crucial to measure how it performs on data that is new to the model and ensures that it is not "overtrained", i.e. that it not only performs well on training data, but that it is able to apply learning on new data that may be generated on a day-to-day basis.

When evaluating a model, in addition to accuracy, it is also common to consider:

- Confidence in predictions: assess how confident the predictions made are.

- Response speed: time taken by the model to process and generate a prediction.

- Resource efficiency: measure how much memory and computational usage the model requires.

- Adaptability: how well the model can be adjusted to new data or conditions without complete retraining.

Step 7: Deploy and maintain the model

When the model meets our expectations, it is ready to be deployed in a real environment. This could involve integrating the model into an application, automating tasks or generating reports.

However, the work does not end here. The AI needs continuous maintenance to adapt to changes in data or real-world conditions. For example, if buying patterns change due to a new trend, the model will need to be updated.

Building AI models is not an exact science, it is the result of a structured process that combines logic, creativity and perseverance. This is because multiple factors are involved, such as data quality, model design choices and human decisions during optimisation. Although clear methodologies and advanced tools exist, model building requires experimentation, fine-tuning and often an iterative approach to obtain satisfactory results. While each step requires attention to detail, the tools and technologies available today make this challenge accessible to anyone interested in exploring the world of AI.

ANNEX I - Definitions Types of models

-

Regression: supervised techniques that model the relationship between a dependent variable (outcome) and one or more independent variables (predictors). Regression is used to predict continuous values, such as future sales or temperatures, and may include approaches such as linear, logistic or polynomial regression, depending on the complexity of the problem and the relationship between the variables.

-

Decision tree models: supervised methods that represent decisions and their possible consequences in the form of a tree. At each node, a decision is made based on a characteristic of the data, dividing the set into smaller subsets. These models are intuitive and useful for classification and prediction, as they generate clear rules that explain the reasoning behind each decision.

-

Clustering models: unsupervised techniques that group data into subsets called clusters, based on similarities or proximity between the data. For example, customers with similar buying habits can be grouped together to personalise marketing strategies. Models such as k-means or DBSCAN allow useful patterns to be identified without the need for labelled data.

-

Time series models: designed to work with chronologically ordered data, these models analyse temporal patterns and make predictions based on history. They are used in cases such as demand forecasting, financial analysis or meteorology. They incorporate trends, seasonality and relationships between past and future data.

-

Neural networks: models inspired by the workings of the human brain, where layers of artificial neurons process information and detect complex patterns. They are especially useful in tasks such as image recognition, natural language processing and gaming. Neural networks can be simple or deep learning, depending on the problem and the amount of data.

-

Supervised models: these models learn from labelled data, i.e., sets in which each input has a known outcome. The aim is for the model to generalise to predict outcomes in new data. Examples include spam and non-spam mail classification and price predictions.

-

Unsupervised models: twork with unlabelled data, looking for hidden patterns, structures or relationships within the data. They are ideal for exploratory tasks where the expected outcome is not known in advance, such as market segmentation or dimensionality reduction.

- Reinforcement learning model: in this approach, an agent learns by interacting with an environment, making decisions and receiving rewards or penalties based on performance. This type of learning is useful in problems where decisions affect a long-term goal, such as training robots, playing video games or developing investment strategies.

Content prepared by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies linked to the data economy. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Web API design is a fundamental discipline for the development of applications and services, facilitating the fluid exchange of data between different systems. In the context of open data platforms, APIs are particularly important as they allow users to access the information they need automatically and efficiently, saving costs and resources.

This article explores the essential principles that should guide the creation of effective, secure and sustainable web APIs, based on the principles compiled by the Technical Architecture Group linked to the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), following ethical and technical standards. Although these principles refer to API design, many are applicable to web development in general.

The aim is to enable developers to ensure that their APIs not only meet technical requirements, but also respect users' privacy and security, promoting a safer and more efficient web for all.

In this post, we will look at some tips for API developers and how they can be put into practice.

Prioritise user needs

When designing an API, it is crucial to follow the hierarchy of needs established by the W3C:

- First, the needs of the end-user.

- Second, the needs of web developers.

- Third, the needs of browser implementers.

- Finally, theoretical purity.

In this way we can drive a user experience that is intuitive, functional and engaging. This hierarchy should guide design decisions, while recognising that sometimes these levels are interrelated: for example, an API that is easier for developers to use often results in a better end-user experience.

Ensures security

Ensuring security when developing an API is crucial to protect both user data and the integrity of the system. An insecure API can be an entry point for attackers seeking to access sensitive information or compromise system functionality. Therefore, when adding new functionalities, we must meet the user's expectations and ensure their security.

In this sense, it is essential to consider factors related to user authentication, data encryption, input validation, request rate management (or Rate Limiting, to limit the number of requests a user can make in a given period and avoid denial of service attacks), etc. It is also necessary to continually monitor API activities and keep detailed logs to quickly detect and respond to any suspicious activity.

Develop a user interface that conveys trust and confidence

It is necessary to consider how new functionalities impact on user interfaces. Interfaces must be designed so that users can trust and verify that the information provided is genuine and has not been falsified. Aspects such as the address bar, security indicators and permission requests should make it clear who you are interacting with and how.

For example, the JavaScript alert function, which allows the display of a modal dialogue box that appears to be part of the browser, is a case history that illustrates this need. This feature, created in the early days of the web, has often been used to trick users into thinking they are interacting with the browser, when in fact they are interacting with the web page. If this functionality were proposed today, it would probably not be accepted because of these security risks.

Ask for explicit consent from users

In the context of satisfying a user need, a website may use a function that poses a threat. For example, access to the user's geolocation may be helpful in some contexts (such as a mapping application), but it also affects privacy.

In these cases, the user's consent to their use is required. To do this:

- The user must understand what he or she is accessing. If you cannot explain to a typical user what he or she is consenting to in an intelligible way, you will have to reconsider the design of the function.

- The user must be able to choose to effectively grant or refuse such permission. If a permission request is rejected, the website will not be able to do anything that the user thinks they have dismissed.

By asking for consent, we can inform the user of what capabilities the website has or does not have, reinforcing their confidence in the security of the site. However, the benefit of a new feature must justify the additional burden on the user in deciding whether or not to grant permission for a feature.

Uses identification mechanisms appropriate to the context

It is necessary to be transparent and allow individuals to control their identifiers and the information attached to them that they provide in different contexts on the web.

Functionalities that use or rely on identifiers linked to data about an individual carry privacy risks that may go beyond a single API or system. This includes passively generated data (such as your behaviour on the web) and actively collected data (e.g. through a form). In this regard, it is necessary to understand the context in which they will be used and how they will be integrated with other web functionalities, ensuring that the user can give appropriate consent.

It is advisable to design APIs that collect the minimum amount of data necessary and use short-lived temporary identifiers, unless a persistent identifier is absolutely necessary.

Creates functionalities compatible with the full range of devices and platforms

As far as possible, ensure that the web functionalities are operational on different input and output devices, screen sizes, interaction modes, platforms and media, favouring user flexibility.

For example, the 'display: block', 'display: flex' and 'display: grid' layout models in CSS, by default, place content within the available space and without overlaps. This way they work on different screen sizes and allow users to choose their own font and size without causing text overflow.

Add new capabilities with care

Adding new capabilities to the website requires consideration of existing functionality and content, to assess how it will be integrated. Do not assume that a change is possible or impossible without first verifying it.

There are many extension points that allow you to add functionality, but there are changes that cannot be made by simply adding or removing elements, because they could generate errors or affect the user experience. It is therefore necessary to verify the current situation first, as we will see in the next section.

Before removing or changing functionality, understand its current use

It is possible to remove or change functions and capabilities, but the nature and extent of their impact on existing content must first be understood. This may require investigating how current functions are used.

The obligation to understand existing use applies to any function on which the content depends. Web functions are not only defined in the specifications, but also in the way users use them.

Best practice is to prioritise compatibility of new features with existing content and user behaviour. Sometimes a significant amount of content may depend on a particular behaviour. In these situations, it is not advisable to remove or change such behaviour.

Leave the website better than you found it

The way to add new capabilities to a web platform is to improve the platform as a whole, e.g. its security, privacy or accessibility features.

The existence of a defect in a particular part of the platform should not be used as an excuse to add or extend additional functionalities in order to fix it, as this may duplicate problems and diminish the overall quality of the platform. Wherever possible, new web capabilities should be created that improve the overall quality of the platform, mitigating existing shortcomings across the board.

Minimises user data

Functionalities must be designed to be operational with the minimal amount of user input necessary to achieve their objectives. In doing so, we limit the risks of disclosure or misuse.

It is recommended to design APIs so that websites find it easier to request, collect and/or transmit a small amount of data (more granular or specific data), than to work with more generic or massive data. APIs should provide granularity and user controls, in particular if they work on personal data.

Other recommendations

The document also provides tips for API design using various programming languages. In this sense, it provides recommendations linked to HTML, CSS, JavaScript, etc. You can read the recommendations here.

In addition, if you are thinking of integrating an API into your open data platform, we recommend reading the Practical guide to publishing Open Data using APIs.

By following these guidelines, you will be able to develop consistent and useful websites for users, allowing them to achieve their objectives in an agile and resource-optimised way.

The EU Open Data Days 2025 is an essential event for all those interested in the world of open data and innovation in Europe and the world. This meeting, to be held on 19-20 March 2025, will bring together experts, practitioners, developers, researchers and policy makers to share knowledge, explore new opportunities and address the challenges facing the open data community.

The event, organised by the European Commission through data.europa.eu, aims to promote the re-use of open data. Participants will have the opportunity to learn about the latest trends in the use of open data, discover new tools and discuss the policies and regulations that are shaping the digital landscape in Europe.

Where and when does it take place?

El evento se celebrará en el Centro Europeo de Convenciones de Luxemburgo, aunque también se podrá seguir online, con el siguiente horario:

- Wednesday 19 March 2025, from 13:30 to 18:30.

- Thursday 20 March 2025, from 9:00 to 15:30.

What issues will be addressed?

The agenda of the event is already available, where we find different themes, such as, for example:

- Success stories and best practices: the event will be attended by professionals working at the frontline of European data policy to share their experience. Among other issues, these experts will provide practical guidance on how to inventory and open up a country's public sector data, address the work involved in compiling high-value datasets or analyse perspectives on data reuse in business models. Good practices for quality metadata or improved data governance and interoperability will also be explained.

- Focus on the use of artificial intelligence (AI): open data offers an invaluable source for the development and advancement of AI. In addition, AI can optimise the location, management and use of this data, offering tools to help streamline processes and extract greater insight. In this regard, the event will address the potential of AI to transform open government data ecosystems, fostering innovation, improving governance and enhancing citizen participation. The managers of Norway's national data portal will tell how they use an AI-based search engine to improve data localisation. In addition, the advances in linguistic data spaces and their use in language modelling will be explained, and how to creatively combine open data for social impact will be explored.

- Learning about data visualisation: event attendees will be able to explore how data visualisation is transforming communication, policy making and citizen engagement. Through various cases (such as the family tree of 3,000 European royals or UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage relationships) it will show how iterative design processes can uncover hidden patterns in complex networks, providing insights into storytelling and data communication. It will also address how design elements such as colour, scale and focus influence the perception of data.

- Examples and use cases: multiple examples of concrete projects based on the reuse of data will be shown, in fields such as energy, urban development or the environment. Among the experiences that will be shared is a Spanish company, Tangible Data, which will tell how physical data sculptures turn complex datasets into accessible and engaging experiences.

These are just some of the topics to be addressed, but there will also be discussions on open science, the role of open data in transparency and accountability, etc.

Why are EU Open Data Days so important?

Access to open data has proven to be a powerful tool for improving decision-making, driving innovation and research, and improving the efficiency of organisations. At a time when digitisation is advancing rapidly, the importance of sharing and reusing data is becoming increasingly crucial to address global challenges such as climate change, public health or social justice.

The EU Open Data Days 2025 are an opportunity to explore how open data can be harnessed to build a more connected, innovative and participatory Europe.

In addition, for those who choose to attend in person, the event will also be an opportunity to establish contacts with other professionals and organisations in the sector, creating new collaborations that can lead to innovative projects.

How can I attend?

To attend in person, it is necessary to register through this link. However, registration is not required to attend the event online.

If you have any queries, an e-mail address has been set up to answer any questions you may have about the event: EU-Open-Data-Days@ec.europa.eu.

More information on the event website.

In an increasingly data-driven world, all organisations, both private companies and public bodies, are looking to leverage their information to make better decisions, improve the efficiency of their processes and meet their strategic objectives. However, creating an effective data strategy is a challenge that should not be underestimated.

Often, organisations in all sectors fall into common mistakes that can compromise the success of their strategies from the outset. From ignoring the importance of data governance to not aligning strategic objectives with the real needs of the institution, these failures can result in inefficiencies, non-compliance with regulations and even loss of trust by citizens, employees or users.

In this article, we will explore the most common mistakes in creating a data strategy, with the aim of helping both public and private entities to avoid them. Our goal is to provide you with the tools to build a solid foundation to maximise the value of data for the benefit of your mission and objectives.

Figure 1. Tips for designing a data governance strategy. Source: own elaboration.

The following are some of the most common mistakes in developing a data strategy, justifying their impact and the extent to which they can affect an organisation:

Lack of linkage to organisational objectives and failure to identify key areas

For data strategy to be effective in any type of organisation, it is essential that it is aligned with its strategic objectives. These objectives include key areas such as revenue growth, service improvement, cost optimisation and customer/citizen experience. In addition, prioritising initiatives is essential to identify the areas of the organisation that will benefit most from the data strategy. This approach not only allows maximising the return on data investment, but also ensures that initiatives are clearly connected to desired outcomes, reducing potential gaps between data efforts and strategic objectives.

Failure to define clear short- and medium-term objectives

Defining specific and achievable goals in the early stages of a data strategy is very important to set a clear direction and demonstrate its value from the outset. This boosts the motivation of the teams involved and builds trust between leaders and stakeholders. Prioritising short-term objectives, such as implementing a dashboard of key indicators or improving the quality of a specific set of critical data, delivers tangible results quickly and justifies the investment in the data strategy. These initial achievements not only consolidate management support, but also strengthen the commitment of the teams.

Similarly, medium-term objectives are essential to build on initial progress and prepare the ground for more ambitious projects. For example, the automation of reporting processes or the implementation of predictive models for key areas can be intermediate goals that demonstrate the positive impact of the strategy on the organisation. These achievements allow us to measure progress, evaluate the success of the strategy and ensure that it is aligned with the organisation's strategic priorities.

Setting a combination of short- and medium-term goals ensures that the data strategy remains relevant over time and continues to generate value. This approach helps the organisation to move forward in a structured way, strengthening its position both vis-à-vis its competitors and in fulfilling its mission in the case of public bodies.

Failure to conduct a maturity assessment beforehand to define the strategy as narrowly as possible.

Before designing a data strategy, it is crucial to conduct a pre-assessment to understand the current state of the organisation in terms of data and to realistically and effectively scope it. This step not only prevents efforts from being dispersed, but also ensures that the strategy is aligned with the real needs of the organisation, thus maximising its impact. Without prior assessment, it is easy to fall into the error of taking on initiatives that are too broad or poorly connected to strategic priorities .

Therefore, conducting this pre-assessment is not only a technical exercise, but a strategic tool to ensure that resources and efforts are well targeted from the outset. With a clear diagnosis, the data strategy becomes a solid roadmap, capable of generating tangible results from the earliest stages. It should be recalled that the UNE 0080:2023, which focuses on the assessment of the maturity of data governance and management, provides a structured framework for this initial assessment. This standard allows for an objective analysis of the organisation's processes, technologies and capabilities around data..

Failure to carry out data governance initiatives

The definition of a sound strategy is fundamental to the success of data governance initiatives. It is essential to have an area or unit responsible for data governance, such as a data office or a centre of excellence, where clear guidelines are established and the necessary actions are coordinated to achieve the committed strategic objectives. These initiatives must be aligned with the organisation's priorities, ensuring that the data is secure, usable for its intended purpose and compliant with applicable laws and regulations.

A robust data governance framework is key to ensuring consistency and quality of data, strengthening confidence in reporting and analysis that generates both internal and external value. In addition, an appropriate approach reduces risks such as non-compliance, promoting effective use of data and protecting the organisation's reputation.

It is therefore important to design these initiatives with a holistic approach, prioritising collaboration between different areas and aligning them with the overall data strategy. For more information on how to structure an effective data governance system, see this series of articles: From data strategy to data governance system - Part 1.

Focusing exclusively on technology

Many organisations have the mistaken view that acquiring sophisticated tools and platforms will be the ultimate solution to their data problems. However, technology is only one part of the ecosystem. Without the right processes, governance framework and, of course, people, even the best technology will fail. This is problematic because it can lead to huge investments with no clear return, as well as frustration among teams when they do not get the expected results.

Failure to involve all stakeholders and define roles and responsibilities

A sound data strategy needs to bring together all relevant actors, whether in a public administration or in a private company. Each area, department or unit has a unique vision of how data can be useful to achieve objectives, improve services or make more informed decisions. Therefore, involving all stakeholders from the outset not only enriches the strategy, but also ensures that they are aligned with the real needs of the organisation.

Likewise, defining clear roles and responsibilities is key to avoid confusion and duplication. Knowing who is responsible for the data, who manages it and who uses it ensures a more efficient workflow and fosters collaboration between teams. In both the public and private spheres, this approach helps to maximise the impact of the data strategy, ensuring that efforts are coordinated and focused towards a common goal.

Failure to establish clear metrics of success

Establishing key performance indicators (KPIs) is essential to assess whether initiatives are generating value. KPIs help demonstrate the results of the data strategy, reinforcing leadership support and encouraging willingness to invest in the future. By measuring the impact of actions, organisations can guarantee the sustainability and continuous development of their strategy, ensuring that it is aligned with strategic objectives and delivers tangible benefits.

Failure to place data quality at the centre

A sound data strategy must be built on a foundation of reliable and high quality data. Ignoring this aspect can lead to wrong decisions, inefficient processes and loss of trust in data by teams. Data quality is not just a technical aspect, but a strategic enabler: it ensures that the information used is complete, consistent, valid and timely.

Integrating data quality from the outset involves defining clear metrics, establishing validation and cleansing processes, and assigning responsibilities for their maintenance. Furthermore, by placing data quality at the heart of the strategy, organisations can unlock the true potential of data, ensuring that it accurately supports business objectives and reinforces user confidence. Without quality, the strategy loses momentum and becomes a wasted opportunity.

Failure to manage cultural change and resistance to change

The transition to a data-driven organisation requires not only tools and processes, but also a clear focus on change management to engage employees. Promoting an open mind towards new practices is key to ensuring the adoption and success of the strategy. By prioritising communication, training and team engagement, organisations can facilitate this cultural change, ensuring that all levels work in alignment with strategic objectives and maximising the impact of the data strategy.

Not planning for scalability

It is critical for organisations to consider how their data strategy can scale as the volume of information grows. Designing a strategy ready to handle this growth ensures that systems can support the increase in data without the need for future restructuring, optimising resources and avoiding additional costs. By planning for scalability, organisations can ensure long-term sustainable operational efficiency and maximise the value of their data as their needs evolve.

Lack of continuous updating and review of the strategy

Data and organisational needs are constantly evolving, so it is important to regularly review and adapt the strategy to keep it relevant and effective. A flexible and up-to-date data strategy allows you to respond nimbly to new opportunities and challenges, ensuring that you continue to deliver value as market or organisational priorities change. This proactive approach ensures that the strategy remains aligned with strategic objectives and reinforces its long-term positive impact.

In conclusion, it is important to highlight that the success of a data strategy lies in its ability to align with the strategic objectives of the organisation, setting clear goals and encouraging the participation of all areas involved. A good data governance system, accompanied by metrics to measure its impact, is the basis for ensuring that the strategy generates value and is sustainable over time.

In addition, addressing issues such as data quality, cultural change and scalability from the outset is essential to maximise its effectiveness. Focusing exclusively on technology or neglecting these elements can limit results and jeopardise the organisation's ability to adapt to new opportunities and challenges. Finally, continuously reviewing and updating the strategy ensures its relevance and reinforces its positive impact.

To learn more about how to structure an effective data strategy and its connection with a solid data governance system, we recommend exploring the articles published in datos.gob.es: From Data Strategy to Data Governance System - Part 1 and Part 2.. These resources complement the concepts presented in this article and offer practical insights for implementation in any type of organisation.

Content elaborated by Dr. Fernando Gualo, Professor at UCLM and Data Governance and Quality Consultant. The content and the point of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The ability to collect, analyse and share data plays a crucial role in the context of the global challenges we face as a society today. From pollution and climate change, through poverty and pandemics, to sustainable mobility and lack of access to basic services. Global problems require solutions that can be adapted on a large scale. This is where open data can play a key role, as it allows governments, organisations and citizens to work together in a transparent way, and facilitates the process of achieving effective, innovative, adaptable and sustainable solutions.

The World Bank as a pioneer in the comprehensive use of open data

One of the most relevant examples of good practices that we can find when it comes to expressing the potential of open data to tackle major global challenges is, without a doubt, the case of the World Bank, a benchmark in the use of open data for more than a decade now as a fundamental tool for sustainable development.

Since the launch of its open data portal in 2010, the institution has undergone a complete transformation process in terms of data access and use. This portal, totally innovative at the time, quickly became a reference model by offering free and open access to a wide range of data and indicators covering more than 250 economies. Moreover, its platform is constantly being updated and bears little resemblance to the initial version at present, as it is continuously improving and providing new datasets and complementary and specialised tools with the aim of making data always accessible and useful for decision making. Examples of such tools include:

- The Poverty and Inequality Platform (PIP): designed to monitor and analyse global poverty and inequality. With data from more than 140 countries, this platform allows users to access up-to-date statistics and better understand the dynamics of collective well-being. It also facilitates data visualisation through interactive graphs and maps, helping users to gain a clear and quick understanding of the situation in different regions and over time.

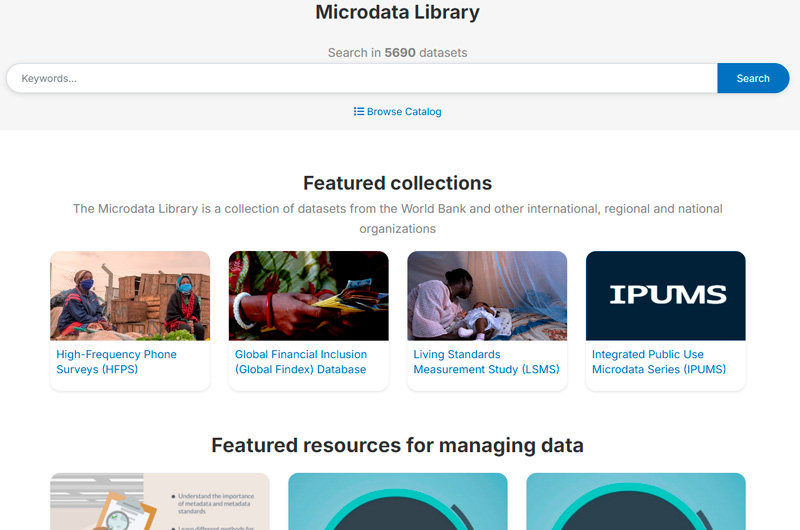

- The Microdata Library: provides access to household and enterprise level survey and census data in several countries. The library has more than 3,000 datasets from studies and surveys conducted by the Bank itself, as well as by other international organisations and national statistical agencies. The data is freely available and fully accessible for downloading and analysis.

- The World Development Indicators (WDI): are an essential tool for tracking progress on the global development agenda. This database contains a vast collection of economic, social and environmental development indicators, covering more than 200 countries and territories. It has data covering areas such as poverty, education, health, environmental sustainability, infrastructure and trade. The WDIs provide us with a reliable frame of reference for analysing global and regional development trends.

Figure 1. Screenshots of the web portals Poverty and Inequality Platform (PIP), Microdata Library and World Development Indicators (WDI).

Data as a transformative element for change

A major milestone in the World Bank's use of data was the publication of the World Development Report 2021, entitled "data for better lives". This report has become a flagship publication that explores the transformative potential of data to address humanity's grand challenges, improve the results of development efforts and promote inclusive and equitable growth. Through the report, the institution advocates a new social agenda for data, including robust, ethical and responsible governance of data, maximising its value in order to generate significant economic and social benefit.

The report examines how data can be integrated into public policy and development programmes to address global challenges in areas such as education, health, infrastructure and climate change. But it also marked a turning point in reinforcing the World Bank's commitment to data as a driver of change in tackling major challenges, and has since adopted a new roadmap with a more innovative, transformative and action-oriented approach to data use. Since then, they have been moving from theory to practice through their own projects, where data becomes a fundamental tool throughout the strategic cycle, as in the following examples:

- Open Data and Disaster Risk Reduction: the report "Digital Public Goods for Disaster Risk Reduction in a Changing Climate" highlights how open access to geospatial and meteorological data facilitates more effective decision-making and strategic planning. Reference is also made to tools such as OpenStreetMap that allow communities to map vulnerable areas in real time. This democratisation of data strengthens emergency response and builds the resilience of communities at risk from floods, droughts and hurricanes.

- Open data in the face of agri-food challenges: the report "What's cooking?" shows how open data is revolutionising global agri-food systems, making them more inclusive, efficient and sustainable. In agriculture, access to open data on weather patterns, soil quality and market prices empowers smallholder farmers to make informed decisions. In addition, platforms that provide open geospatial data serve to promote precision agriculture, enabling the optimisation of key resources such as water and fertilisers, while reducing costs and minimising environmental impact.

- Optimising urban transport systems: in Tanzania, the World Bank has supported a project that uses open data to improve the public transport system. The rapid urbanisation of Dar es Salaam has led to considerable traffic congestion in several areas, affecting both urban mobility and air quality. This initiative addresses traffic congestion through a real-time information system that improves mobility and reduces environmental impact. This approach, based on open data, not only increases transport efficiency, but also contributes to a better quality of life for city dwellers.

Leading by example

Finally, and within this same comprehensive vision, it is worth noting how this international organization closes the circle of open data through its use as a tool for transparency and communication of its own activities.That is why among the outstanding data tools in its catalogue we can find some of them:

- Its project and operations portal: a tool that provides detailed access to the development projects that the institution funds and implements around the world. This portal acts as a window into all its global initiatives, providing information on objectives, funding, expected results and progress for the Bank's thousands of projects.

- The Finances One platform: on which they centralise all their financial data of public interest and those corresponding to the project portfolio of all the group's entities. It aims to simplify the presentation of financial information, facilitating its analysis and sharing by customers and partners.

The future impact of open data on major global challenges

As we have also seen above, opening up data offers immense potential to advance the sustainable development agenda and thus be able to address global challenges more effectively. The World Bank has been demonstrating how this practice can evolve and adapt to current challenges. Its leadership in this area has served as a model for other institutions, showing the positive impact that open data can have on sustainable development and in tackling the major challenges affecting the lives of millions of people around the world.

However, there is still a long way to go, as transparency and access to information policies need to be further improved so that data can reach the benefit of society as a whole in a more equitable way. In addition, another key challenge is to strengthen the capacities needed to maximise the use and impact of this data, particularly in developing countries. This implies not only going beyond facilitating access, but also working on data literacy and supporting the creation of the right tools to enable information to be used effectively.

The use of open data is enabling more and more actors to participate in the creation of innovative solutions and bring about real change. All this gives rise to a new and expanding area of work that, in the right hands and with the right support, can play a crucial role in creating a safer, fairer and more sustainable future for all. We hope that many organisations will follow the World Bank's example and also adopt a holistic approach to using data to address humanity's grand challenges.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

There is no doubt that data has become the strategic asset for organisations. Today, it is essential to ensure that decisions are based on quality data, regardless of the alignment they follow: data analytics, artificial intelligence or reporting. However, ensuring data repositories with high levels of quality is not an easy task, given that in many cases data come from heterogeneous sources where data quality principles have not been taken into account and no context about the domain is available.

To alleviate as far as possible this casuistry, in this article, we will explore one of the most widely used libraries in data analysis: Pandas. Let's check how this Python library can be an effective tool to improve data quality. We will also review the relationship of some of its functions with the data quality dimensions and properties included in the UNE 0081 data quality specification, and some concrete examples of its application in data repositories with the aim of improving data quality.

Using Pandas for data profiling

Si bien el data profiling y la evaluación de calidad de datos están estrechamente relacionados, sus enfoques son diferentes:

- Data Profiling: is the process of exploratory analysis performed to understand the fundamental characteristics of the data, such as its structure, data types, distribution of values, and the presence of missing or duplicate values. The aim is to get a clear picture of what the data looks like, without necessarily making judgements about its quality.

- Data quality assessment: involves the application of predefined rules and standards to determine whether data meets certain quality requirements, such as accuracy, completeness, consistency, credibility or timeliness. In this process, errors are identified and actions to correct them are determined. A useful guide for data quality assessment is the UNE 0081 specification.

It consists of exploring and analysing a dataset to gain a basic understanding of its structure, content and characteristics, before conducting a more in-depth analysis or assessment of the quality of the data. The main objective is to obtain an overview of the data by analysing the distribution, types of data, missing values, relationships between columns and detection of possible anomalies. Pandas has several functions to perform this data profiling.

En resumen, el data profiling es un paso inicial exploratorio que ayuda a preparar el terreno para una evaluación más profunda de la calidad de los datos, proporcionando información esencial para identificar áreas problemáticas y definir las reglas de calidad adecuadas para la evaluación posterior.

What is Pandas and how does it help ensure data quality?

Pandas is one of the most popular Python libraries for data manipulation and analysis. Its ability to handle large volumes of structured information makes it a powerful tool in detecting and correcting errors in data repositories. With Pandas, complex operations can be performed efficiently, from data cleansing to data validation, all of which are essential to maintain quality standards. The following are some examples of how to improve data quality in repositories with Pandas:

1. Detection of missing or inconsistent values: One of the most common data errors is missing or inconsistent values. Pandas allows these values to be easily identified by functions such as isnull() or dropna(). This is key for the completeness property of the records and the data consistency dimension, as missing values in critical fields can distort the results of the analyses.

-

# Identify null values in a dataframe.

df.isnull().sum()

2. Data standardisation and normalisation: Errors in naming or coding consistency are common in large repositories. For example, in a dataset containing product codes, some may be misspelled or may not follow a standard convention. Pandas provides functions like merge() to perform a comparison with a reference database and correct these values. This option is key to maintaining the dimension and semantic consistency property of the data.

# Substitution of incorrect values using a reference table

df = df.merge(product_codes, left_on='product_code', right_on='ref_code', how= 'left')

3. Validation of data requirements: Pandas allows the creation of customised rules to validate the compliance of data with certain standards. For example, if an age field should only contain positive integer values, we can apply a function to identify and correct values that do not comply with this rule. In this way, any business rule of any of the data quality dimensions and properties can be validated.

# Identify records with invalid age values (negative or decimals)

age_errors = df[(df['age'] < 0) | (df['age'] % 1 != 0)])

4. Exploratory analysis to identify anomalous patterns: Functions such as describe() or groupby() in Pandas allow you to explore the general behaviour of your data. This type of analysis is essential for detecting anomalous or out-of-range patterns in any data set, such as unusually high or low values in columns that should follow certain ranges.

# Statistical summary of the data

df.describe()

#Sort by category or property

df.groupby()

5. Duplication removal: Duplicate data is a common problem in data repositories. Pandas provides methods such as drop_duplicates() to identify and remove these records, ensuring that there is no redundancy in the dataset. This capacity would be related to the dimension of completeness and consistency.

# Remove duplicate rows

df = df.drop_duplicates()

Practical example of the application of Pandas

Having presented the above functions that help us to improve the quality of data repositories, we now consider a case to put the process into practice. Suppose we are managing a repository of citizens' data and we want to ensure:

- Age data should not contain invalid values (such as negatives or decimals).

- That nationality codes are standardised.

- That the unique identifiers follow a correct format.

- The place of residence must be consistent.

With Pandas, we could perform the following actions:

1. Age validation without incorrect values:

# Identify records with ages outside the allowed ranges (e.g. less than 0 or non-integers)

age_errors = df[(df['age'] < 0) | (df['age'] % 1 != 0)])

2. Correction of nationality codes:

# Use of an official dataset of nationality codes to correct incorrect entries

df_corregida = df.merge(nacionalidades_ref, left_on='nacionalidad', right_on='codigo_ref', how='left')

3. Validation of unique identifiers:

# Check if the format of the identification number follows a correct pattern

df['valid_id'] = df['identificacion'].str.match(r'^[A-Z0-9]{8}$')

errores_id = df[df['valid_id'] == False]

4. Verification of consistency in place of residence:

# Detect possible inconsistencies in residency (e.g. the same citizen residing in two places at the same time).

duplicados_residencia = df.groupby(['id_ciudadano', 'fecha_residencia'])['lugar_residencia'].nunique()

inconsistencias_residencia = duplicados_residencia[duplicados_residencia > 1]

Integration with a variety of technologies

Pandas is an extremely flexible and versatile library that integrates easily with many technologies and tools in the data ecosystem. Some of the main technologies with which Pandas is integrated or can be used are:

- SQL databases:

Pandas integrates very well with relational databases such as MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQLite, and others that use SQL. The SQLAlchemy library or directly the database-specific libraries (such as psycopg2 for PostgreSQL or sqlite3) allow you to connect Pandas to these databases, perform queries and read/write data between the database and Pandas.

- Common function: pd.read_sql() to read a SQL query into a DataFrame, and to_sql() to export the data from Pandas to a SQL table.

- REST and HTTP-based APIs:

Pandas can be used to process data obtained from APIs using HTTP requests. Libraries such as requests allow you to get data from APIs and then transform that data into Pandas DataFrames for analysis.

- Big Data (Apache Spark):

Pandas can be used in combination with PySpark, an API for Apache Spark in Python. Although Pandas is primarily designed to work with in-memory data, Koalas, a library based on Pandas and Spark, allows you to work with Spark distributed structures using a Pandas-like interface. Tools like Koalas help Pandas users scale their scripts to distributed data environments without having to learn all the PySpark syntax.

- Hadoop and HDFS:

Pandas can be used in conjunction with Hadoop technologies, especially the HDFS distributed file system. Although Pandas is not designed to handle large volumes of distributed data, it can be used in conjunction with libraries such as pyarrow or dask to read or write data to and from HDFS on distributed systems. For example, pyarrow can be used to read or write Parquet files in HDFS.

- Popular file formats:

Pandas is commonly used to read and write data in different file formats, such as:

- CSV: pd.read_csv()

- Excel: pd.read_excel() and to_excel().

- JSON: pd.read_json()

- Parquet: pd.read_parquet() for working with space and time efficient files.

- Feather: a fast file format for interchange between languages such as Python and R (pd.read_feather()).

- Data visualisation tools:

Pandas can be easily integrated with visualisation tools such as Matplotlib, Seaborn, and Plotly.. These libraries allow you to generate graphs directly from Pandas DataFrames.

- Pandas includes its own lightweight integration with Matplotlib to generate fast plots using df.plot().

- For more sophisticated visualisations, it is common to use Pandas together with Seaborn or Plotly for interactive graphics.

- Machine learning libraries:

Pandas is widely used in pre-processing data before applying machine learning models. Some popular libraries with which Pandas integrates are:

- Scikit-learn: la mayoría de los pipelines de machine learning comienzan con la preparación de datos en Pandas antes de pasar los datos a modelos de Scikit-learn.

- TensorFlow y PyTorch: aunque estos frameworks están más orientados al manejo de matrices numéricas (Numpy), Pandas se utiliza frecuentemente para la carga y limpieza de datos antes de entrenar modelos de deep learning.

- XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost: Pandas supports these high-performance machine learning libraries, where DataFrames are used as input to train models.

- Jupyter Notebooks:

Pandas is central to interactive data analysis within Jupyter Notebooks, which allow you to run Python code and visualise the results immediately, making it easy to explore data and visualise it in conjunction with other tools.

- Cloud Storage (AWS, GCP, Azure):

Pandas can be used to read and write data directly from cloud storage services such as Amazon S3, Google Cloud Storage and Azure Blob Storage. Additional libraries such as boto3 (for AWS S3) or google-cloud-storage facilitate integration with these services. Below is an example for reading data from Amazon S3.

import pandas as pd

import boto3

#Create an S3 client

s3 = boto3.client('s3')

#Obtain an object from the bucket

obj = s3.get_object(Bucket='mi-bucket', Key='datos.csv')

#Read CSV file from a DataFrame

df = pd.read_csv(obj['Body'])

10. Docker and containers:

Pandas can be used in container environments using Docker.. Containers are widely used to create isolated environments that ensure the replicability of data analysis pipelines .

In conclusion, the use of Pandas is an effective solution to improve data quality in complex and heterogeneous repositories. Through clean-up, normalisation, business rule validation, and exploratory analysis functions, Pandas facilitates the detection and correction of common errors, such as null, duplicate or inconsistent values. In addition, its integration with various technologies, databases, big dataenvironments, and cloud storage, makes Pandas an extremely versatile tool for ensuring data accuracy, consistency and completeness.

Content prepared by Dr. Fernando Gualo, Professor at UCLM and Data Governance and Quality Consultant. The content and point of view reflected in this publication is the sole responsibility of its author.

On 11, 12 and 13 November, a new edition of DATAforum Justice will be held in Granada. The event will bring together more than 100 speakers to discuss issues related to digital justice systems, artificial intelligence (AI) and the use of data in the judicial ecosystem.The event is organized by the Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts, with the collaboration of the University of Granada, the Andalusian Regional Government, the Granada City Council and the Granada Training and Management entity.

The following is a summary of some of the most important aspects of the conference.

An event aimed at a wide audience

This annual forum is aimed at both public and private sector professionals, without neglecting the general public, who want to know more about the digital transformation of justice in our country.

The DATAforum Justice 2024 also has a specific itinerary aimed at students, which aims to provide young people with valuable tools and knowledge in the field of justice and technology. To this end, specific presentations will be given and a DATAthon will be set up. These activities are particularly aimed at students of law, social sciences in general, computer engineering or subjects related to digital transformation. Attendees can obtain up to 2 ECTS credits (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System): one for attending the conference and one for participating in the DATAthon.

Data at the top of the agenda

The Paraninfo of the University of Granada will host experts from the administration, institutions and private companies, who will share their experience with an emphasis on new trends in the sector, the challenges ahead and the opportunities for improvement.

The conference will begin on Monday 11 November at 9:00 a.m., with a welcome to the students and a presentation of DATAthon. The official inauguration, addressed to all audiences, will be at 11:35 a.m. and will be given by Manuel Olmedo Palacios, Secretary of State for Justice, and Pedro Mercado Pacheco, Rector of the University of Granada.

From then on, various talks, debates, interviews, round tables and conferences will take place, including a large number of data-related topics. Among other issues, the data management, both in administrations and in companies, will be discussed in depth. It will also address the use of open data to prevent everything from hoaxes to suicide and sexual violence.

Another major theme will be the possibilities of artificial intelligence for optimising the sector, touching on aspects such as the automation of justice, the making of predictions. It will include presentations of specific use cases, such as the use of AI for the identification of deceased persons, without neglecting issues such as the governance of algorithms.

The event will end on Wednesday 13 at 17:00 hours with the official closing ceremony. On this occasion, Félix Bolaños, Minister of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Cortes, will accompany the Rector of the University of Granada.

A Datathon to solve industry challenges through data

In parallel to this agenda, a DATAthon will be held in which participants will present innovative ideas and projects to improve justice in our society. It is a contest aimed at students, legal and IT professionals, research groups and startups.

Participants will be divided into multidisciplinary teams to propose solutions to a series of challenges, posed by the organisation, using data science oriented technologies. During the first two days, participants will have time to research and develop their original solution. On the third day, they will have to present a proposal to a qualified jury. The prizes will be awarded on the last day, before the closing ceremony and the Spanish wine and concert that will bring the 2024 edition of DATAfórum Justicia to a close.

In the 2023 edition, 35 people participated, divided into 6 teams that solved two case studies with public data and two prizes of 1,000 euros were awarded.

How to register

The registration period for the DATAforum Justice 2024 is now open. This must be done through the event website, indicating whether it is for the general public, public administration staff, private sector professionals or the media.