The European open data portal (data.europa.eu) regularly organises virtual training sessions on topical issues in the open data sector, the regulations they affect and related technologies. In this post, we review the key takeaways from the latest webinar on High Value Datasets (HVD).

Among other issues, this seminar focused on transmitting best practices, as well as explaining the experiences of two countries, Finland and the Czech Republic, which were part of the report "High-value Datasets Best Practices in Europe", published by data.europa.eu, together with Denmark, Estonia, Italy, the Netherlands and Romania. The study was conducted immediately after the publication of the HVD implementation regulation in February 2023.

Best practices linked to the provision of high-value data

After an introduction explaining what high-value data are and what requirements they have to meet, the scope of the report was explained in detail during the webinar. In particular, challenges, good practices and recommendations from member states were identified, as detailed below.

Political and legal framework

- There is a need to foster a government culture that is primarily practical and focused on achievable goals, building on cultural values embedded in government systems, such as transparency.

- A strategic approach based on a broader regulatory perspective is recommended, building on previous efforts to implement far-reaching directives such as INSPIRE or DCAT as a standard for data publication. In this respect, it is appropriate to prioritise actions that overlap with these existing initiatives.

- The use of Creative Commons (CC) licences is recommended.

- On a cross-cutting level, another challenge is to combine compliance with the requirements of high-value datasets with the provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), when dealing with sensitive or personal data.

Governance and processes

- Engaging in strategic partnerships and fostering collaboration at national level is encouraged. Among other issues, it is recommended to coordinate efforts between ministries, agencies responsible for different categories of HVD and other related actors, especially in Member States with decentralised governance structures. To this end, it is important to set up interdisciplinary working groups to facilitate a comprehensive data inventory and to clarify which agency is responsible for which dataset. These groups will enable knowledge sharing and foster a sense of community and shared responsibility, which contributes to the overall success of data governance efforts.

- It is recommended to engage in regular exchanges with other Member States, to share ideas and solutions to common challenges.

- There is a need to promote sustainability through the individual accountability of agencies for their respective datasets. Ensuring the sustainability of national data portals means making sure that metadata is maintained with the resources available.

- It is advisable to develop a comprehensive data governance framework by first assessing available resources, including technical expertise, data management tools and key stakeholder input. This assessment process allows for a clear understanding of the rules, processes and responsibilities necessary for an effective implementation of data governance.

Technical aspects, metadata quality and new requirements

- It is proposed to develop a comprehensive understanding of the specific requirements for HVD. This involves identifying existing datasets to determine their compliance with the standards described in the implementing regulation for HVD. There is a need to build a systemic basis for identifying, improving the quality and availability of data by enhancing the overall value of high-value datasets.

- It is recommended to improve the quality of metadata directly at the data source before publishing them in portals, following the DCAT-AP guidelines for publishing high-value datasets and the controlled vocabularies for the six HVD categories. There is also a need to improve the implementation of APIs and bulk downloads from each data source. Its implementation presents significant challenges due to the scarcity of resources and expertise, making capacity building and resourcing essential.

- It is suggested to strengthen the availability of high-value datasets through external funding or strategic planning. The regulation requires all HVD to be accessible free of charge, so some Member States diversify funding sources by seeking financial support through external channels, e.g. by tapping into European projects. In this respect, it is recommended to adapt business models progressively to offer free data.

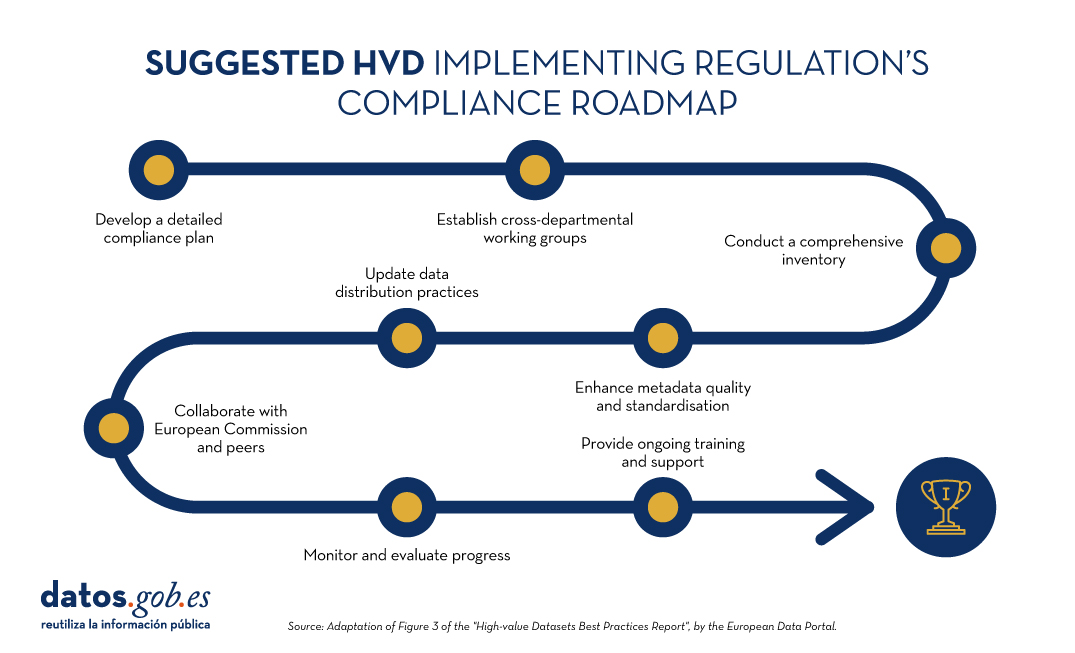

Finally, the report highlights a suggested eight-step roadmap for compliance with the HVD implementation regulation:

Figure 1: Suggested roadmap for HVD implementation. Adapted from Figure 3 of the European Data Portal's "High-value Datasets Best Practices Report".

The example of the Czech Republic

In a second part of the webinar, the Czech Republic presented their implementation case, which they are approaching from four main tasks: motivation, regulatory implementation, responsibility of public data provider agencies and technical requirements.

- Motivation among the different actors is being articulated through the constitution of working groups.

- Regulatory implementation focuses on dataset analysis and consistency or inconsistency with INSPIRE.

- To boost the accountability of public agencies, knowledge-sharing seminars are being held on linking INSPIRE and HVD using the DCAT-AP standard as a publication pathway.

- Regarding technical requirements, DCAT-AP and INSPIRE requirements are being integrated into metadata practices adapted to their national context. The Czech Republic has developed specifications for local open data catalogues to ensure compatibility with the National Open Data Catalogue. However, its biggest challenge is a strong dependency due to a lack of technical capacities.

The example of Finland

Finland then took the floor. Having pre-existing legislation (INSPIRE and other specific rules on open data and information management inpublic bodies), Finland required only minor adjustments to align with the national transposition of the HVD directive. The challenge is to understand and make INSPIRE and HVD coexist.

Its main strategy is based on the roadmap on information management in public bodies, which ensures harmonisation, interoperability, high quality management and security to implement the principles of open data. In addition, they have established two working groups to address the implementation of HVD:

- The first group, which is a coordinating group of data promoters, focused on practical and technical issues. As legal experts, they also provided guidance on understanding HVD regulation from a legal perspective.

- The second group is an inter-ministerial coordination group, a working group that ensures that there is no conflict or overlap between HVD regulation and national legislation. This group manages the inventory, in spreadsheet format, containing all the elements necessary for an HVD catalogue. By identifying areas where datasets do not meet these requirements, organisations can establish a roadmap to address the gaps and ensure full compliance over time.

The secretariat of the groups is provided by a geospatial data committee. Both have a wide network of stakeholders to articulate discussion and feedback on the measures taken.

Looking to the future, they highlight as a challenge the need to gain more technical and executive level experience.

End of the session

The webinar continued with the participation of Compass Gruppe (Germany), which markets, among other things, data from the Austrian commercial register. They have a portal that offers this data via APIs through a freemium business model.

In addition, it was recalled that Member States are obliged to report to Europe every two years on progress in HVD, an activity that is expected to boost the availability of harmonised federated metadata on the European data portal. The idea is that users will be able to find all HVD in the European Union, using the filtering available on the portal or through SPARQL queries.

The combination of the report's conclusions and the experiences of the rapporteur countries give us good clues to guide the implementation of HVD, in compliance with European regulations. In summary, the implementation of HVD poses the following challenges:

- Support the necessary funding to address the opening-up process.

- Overcoming technical challenges to develop efficient access APIs.

- Achieving a proper coexistence between INSPIRE and the HVD regulation

- Consolidate working groups that function as a robust mechanism for progress and convergence.

- Monitor progress and continuously follow up the process.

- Invest in technical training of staff.

- Create and maintain strong coordination in the face of the complex diversity of data holders.

- Potential quality assurance of high value datasets.

- Agree on a standardisation that is necessary from a business point of view.

By addressing these challenges, we will successfully open up high-value data, driving its re-use for the benefit of society as a whole.

You can re-watch the recording of the session here

Data activism is an increasingly significant citizen practice in the platform era for its growing contribution to democracy, social justice and rights. It is an activism that uses data and data analysis to generate evidence and visualisations with the aim of revealing injustices, improving people's lives and promoting social change.

In the face of the massive use of surveillance data by certain corporations, data activism is exercised by citizens and non-governmental organisations. For example, the organisation Forensic Architecture (FA)a centre at Goldsmiths under the University of London, investigates human rights violations, including state violence, using public, citizen and satellite data, and methodologies such as open source intelligence (known as OSINT). The analysis of data and metadata, the synchronisation of video footage taken by witnesses or journalists, as well as official recordings and documents, allows for the reconstruction of facts and the generation of an alternative narrative about events and crises.

Data activism has attracted the interest of research centres and non-governmental organisations, generating a line of work within the discipline of critical studies. This has allowed us to reflect on the effect of data, platforms and their algorithms on our lives, as well as on the empowerment that is generated when citizens exercise their right to data and use it for the common good.

Image 1: Ecocide in Indonesia (2015)

Source: Forensic Architecture (https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/ecocide-in-indonesia)

Research centres such as Datactive o Data + Feminism Lab have created theory and debates on the practice of data activism. Likewise, organisations such as Algorights -a collaborative network that encourages civil society participation in the field of aI technologies- y AlgorithmWatch -a human rights organisation - generate knowledge, networks and arguments to fight for a world in which algorithms and artificial Intelligence (AI) contribute to justice, democracy and sustainability, rather than undermine them.

This article reviews how data activism emerged, what interest it has sparked in social science, and its relevance in the age of platforms.

History of a practice

The production of maps using citizen data could be one of the first manifestations of data activism as it is now known. A seminal map in the history of data activism was generated by victims and activists with data from the 2010 Haiti earthquakeon the Kenyan platform Ushahidi ("testimony" in Swahili). A community of digital humanitarianscreated the map from other countries and called on victims and their families and acquaintances to share data on what was happening in real time. Within hours, the data was verified and visualised on an interactive map that continued to be updated with more data and was instrumental in assisting the victims on the ground. Today, such mapsare generated whenever a crisis arises, and are enriched with citizen, satellite and camera-equipped drone data to clarify events and generate evidence.

Emerging from movements known as cypherpunk and technopositivism or technoptimism (based on the belief that technology is the answer to humanity's challenges), data activism has evolved as a practice to adopt more critical stances towards technology and the power asymmetries that arise between those who originate and hand over their data, and those who capture and analyse it.

Today, for example, the Ushahidi community map production platform has been used to create data on gender-based violence in Egypt and Syria, and on trusted gynaecologists in India, for example. Today, the invisibilisation and silencing of women is the reason why some organisations are fighting for recognition and a policy of visibility, something that became evident with the #MeToo movement. Feminist data practices seek visibility and critical interpretations of datification(or the transformation of all human and non-human action into measurable data that can be transformed into value). For example, Datos Contra el Feminicidio or Feminicidio.net offer maps and data analysis on femicide in various parts of the world.

The potential for algorithmic empowerment offered by these projects removes barriers to equality by improving the conditions conditions that enable women to solve problems, determine how data is collected and used, and exercise power.

Birth and evolution of a concept

In 2015, Citizen Media Meets Big Data: The Rise of Data Activismwas published, in which, for the first time, data activism was coined and defined as a concept based on practices observed in activists who engage politically with data infrastructure. Data infrastructure includes the data, software, hardware and processes needed to turn data into value. Later, Data activism and social change (London, Palgrave) and Data activism and social change. Alliances, maps, platforms and action for a better world (Madrid: Dykinson) develop analytical frameworks based on real cases that offer ways to analyse other cases.

Accompanying the varied practices that exist within data activism, its study is creating spaces for feminist and post-colonialist research on the consequences of datification. Whereas the chroniclers of history (mainly male sources) defined technology in relation to the value of their productsfeminist data studies consider women as users and designers of technology as users and designers of algorithmic systems and seek to use data for equality, and to move away from capitalist exploitation and its structures of domination.

Data activism is now an established concept in social science. For example, Google Scholar offers more than 2,000 results on "data activism". Several researchers use it as a perspective to analyse various issues. For example, Rajão and Jarke explore environmental activism in Brazil; Gezgin studies critical citizenship and its use of data infrastructure; Lehtiniemi and Haapoja explore data agency and citizen participation; and Scott examines the need for platform users to develop digital surveillance and care for their personal data.

At the heart of these concerns is the concept of data agency, which refers to people not only being aware of the value of their data, but also exercising control over it, determining how it is used and shared. It could be defined as actions and practices related to data infrastructure based on individual and collective reflection and interest. That is, while liking a post would not be considered an action with a high degree of data agency, participating in a hackathon - a collective event in which a computer programme is improved or created - would be. Data agency is based on data literacy, or the degree of knowledge, access to data and data tools, and opportunities for data literacy that people have. Data activism is not possible without a data agency.

In the rapidly evolving landscape of the platform economy, the convergence of data activism, digital rights and data agency has become crucial. Data activism, driven by a growing awareness of the potential misuse of personal data, encourages individuals and collectives to use digital technology for social change, as well as to advocate for greater transparency and accountability on the part of tech giants. As more and more data generation and the use of algorithms shape our lives in areas such as education, employment, social services and health, data activism emerges as a necessity and a right, rather than an option.

____________________________________________________________________

Content prepared by Miren Gutiérrez, PhD and researcher at the University of Deusto, expert in data activism, data justice, data literacy and gender disinformation.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The Open Data Maturity Study 2022 provides a snapshot of the level of development of policies promoting open data in countries, as well as an assessment of the expected impact of these policies. Among its findings, it highlights that measuring the impact of open data is a priority, but also a major challenge across Europe.

In this edition, there has been a 7% decrease in the average maturity level in the impact dimension for EU27 countries, which coincides with the restructuring of the impact dimension indicators. However, it is not so much a decrease in the level of maturity, but a more accurate picture of the difficulty in assessing the resulting impact of reuse of open data difficulty in assessing the impact resulting from the re-use of open data.

Therefore, in order to better understand how to make progress on the challenge of measuring the impact of open data, we have looked at existing best practices for measuring the impact of open data in Europe. To achieve this objective, we have worked with the data provided by the countries in their responses to the survey questionnaire and in particular with those of the eleven countries that have scored more than 500 points in the Impact dimension, regardless of their overall score and their position in the ranking: France, Ireland, Cyprus, Estonia and the Czech Republic scoring the maximum 600 points; and Poland, Spain, Italy, Denmark and Sweden scoring above 510 points.

In the report we provide a country profile for each of the ten countries, analysing in general terms the country's performance in all dimensions of the study and in detail the different components of the impact dimension, summarising the practices that have led to its high score based on the analysis of the responses to the questionnaire.

Through this tabbed structure the document allows for a direct comparison between country indicators and provides a detailed overview of best practices and challenges in the use of open data in terms of measuring impact through the following indicators:

- "Strategic awareness": It quantifies the awareness and preparedness of countries to understand the level of reuse and impact of open data within their territory.

- "Measuring reuse": It focuses on how countries measure open data re-use and what methods they use.

-

"Impact created": It collects data on the impact created within four impact areas: government impact (formerly policy impact), social impact, environmental impact and economic impact.

Finally, the report provides a comparative analysis of these countries and draws out a series of recommendations and good practices that aim to provide ideas on how to improve the impact of open data on each of the three indicators measured in the study.

If you want to know more about the content of this report, you can watch the interview with its author interview with its author.

Below, you can download the full report, the executive summary and a presentation-summary.

Content prepared by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization.

The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The Multisectorial Association of Information (ASEDIE), which brings together the infomediary companies of our country, once again includes among its annual objectives the promotion of the reuse of public and private information. Thus, and almost in parallel to the beginning of the new year, last December, ASEDIE shared the progress that the top 3 has experienced in most of the autonomous communities, and the good expectations for the second edition.

Since this initiative was launched last 2019 to promote the opening of three datasets by the autonomous communities, they have been gradually opening datasets that have improved access to information sources, while helping to boost the development of services and applications based on open data. The objective of this project, which in 2021 was included as a commitment to Best Practices in the Observatory of the IV Open Government Plan and supported by the seventeen Autonomous Communities, is to harmonize the opening of Public Sector databases with the aim of encouraging their reuse, promoting the development of the data economy.

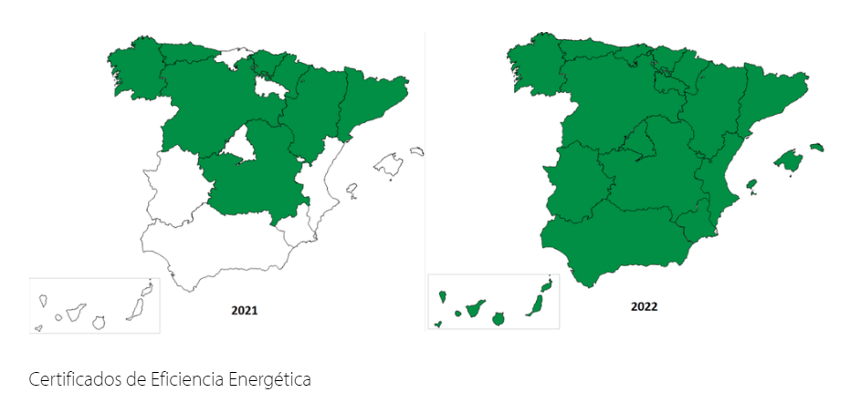

First edition: accessible in fifteen autonomous communities

The first edition of Asedie's Top 3 was a success not only because of the datasets selected, but also because of the openness rate achieved four years later. Currently, fifteen of the country's seventeen autonomous communities have managed to open all three databases to the general public: cooperatives, foundations and associations.

2023: the year to complete the opening of the second edition

With the aim of continuing to promote the opening of public information in the different autonomous communities, in 2020, ASEDIE launched a new edition of the top 3 so that those communities that had already overcome the previous challenge could continue to make progress. Thus, for this second edition the selected databases were the following:

- Energy Efficiency Certificates

- Industrial Estates

- Agricultural Transformation Companie

As a result, the second edition of the top 3 is now accessible in seven autonomous communities. Moreover, the databases related to energy efficiency certificates, an increasingly required information at European level, are now openly available in all the autonomous communities of the Spanish geography.

Next steps: extending the commitment to open data

As it could not be otherwise, one of ASEDIE's main annual objectives is to continue promoting regional collaboration in order to complete the opening of the second edition of the top 3 in the rest of the autonomous communities. In parallel, the next edition of the ASEDIE Report will be made public on March 22, taking advantage of the Open Administration Week. As on other occasions, this document will serve to take stock of the milestones achieved in the previous year, as well as to list the new challenges.

In fact, in relation to open data, the ASEDIE report is a very useful tool when it comes to broadening knowledge in this area of expertise, as it includes a list of successful cases of infomediary companies and examples of the products and services they produce.

In short, thanks to initiatives such as those developed by ASEDIE, public-private collaboration is becoming more and more constant and tangible, making it easier for companies to reuse public information.

16.5 billion euros. These are the revenues that artificial intelligence (AI) and data are expected to generate in Spanish industry by 2025, according to what was announced last February at the IndesIA forum, the association for the application of artificial intelligence in industry. AI is already part of our daily lives: either by making our work easier by performing routine and repetitive tasks, or by complementing human capabilities in various fields through machine learning models that facilitate, for example, image recognition, machine translation or the prediction of medical diagnoses. All of these activities help us to improve the efficiency of businesses and services, driving more accurate decision-making.

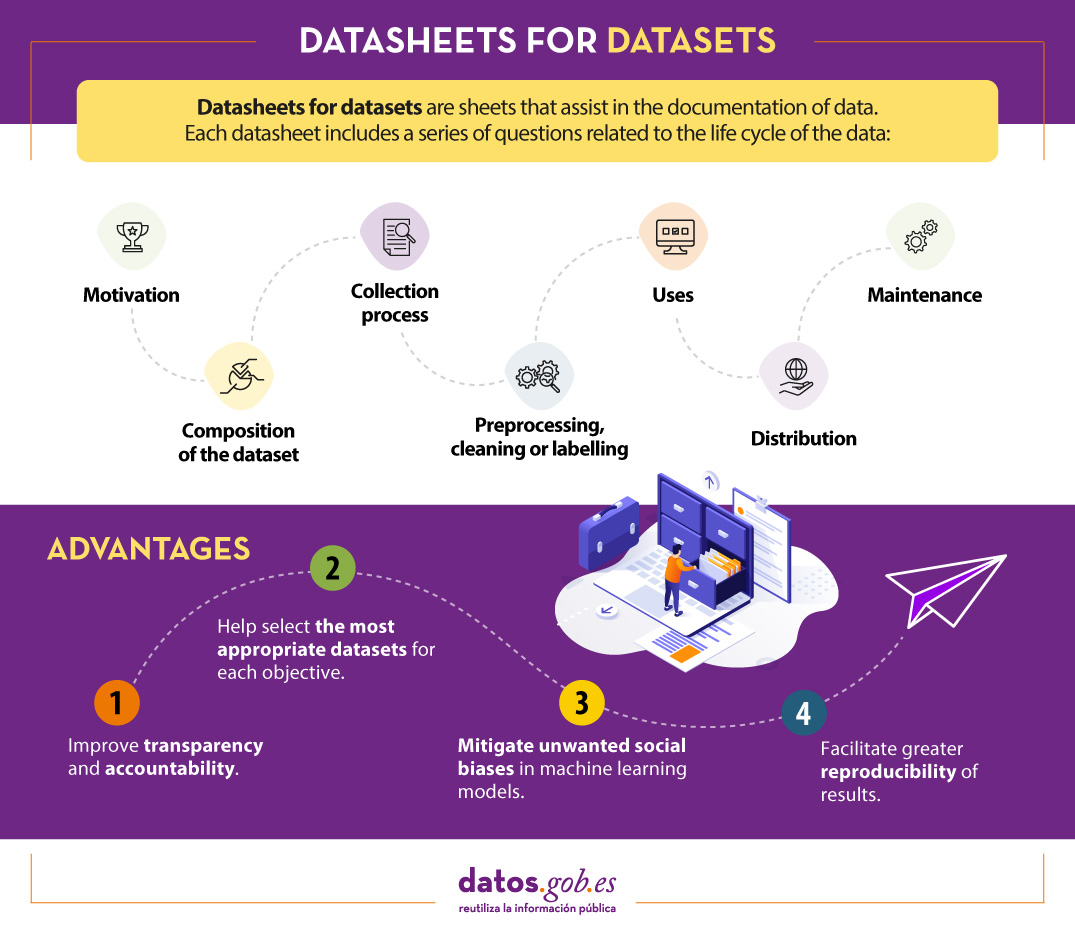

But for machine learning models to work properly, they need quality and well-documented data. Every machine learning model is trained and evaluated with data. The characteristics of these datasets condition the behaviour of the model. For example, if the training data reflects unwanted social biases, these are likely to be incorporated into the model as well, which can have serious consequences when used in high-profile areas such as criminal justice, recruitment or credit lending. Moreover, if we do not know the context of the data, our model may not work properly, as its construction process has not taken into account the intrinsic characteristics of the data on which it is based.

For these and other reasons, the World Economic Forum suggests that all entities should document the provenance, creation and use of machine learning datasets in order to avoid erroneous or discriminatory results..

What are datasheets for datasets?

One mechanism for documenting this information is known as Datasheets for datasets. This framework proposes that every dataset should be accompanied by a datasheet, which consists of a questionnaire that guides data documentation and reflection throughout the data lifecycle. Some of the benefits are:

- It improves collaboration, transparency and accountability within the machine learning community.

- Mitigates unwanted social biases in models.

- Helps researchers and developers select the most appropriate datasets to achieve their specific goals.

- Facilitates greater reproducibility of results.

Datasheets will vary depending on factors such as knowledge area, existing organisational infrastructure or workflows.

To assist in the creation of datasheets, a questionnaire has been designed with a series of questions, according to the stages of the data lifecycle:

- Motivation. Collects the reasons that led to the creation of the datasets. It also asks who created or funded the datasets.

- Composition. Provides users with the necessary information on the suitability of the dataset for their purposes. It includes, among other questions, which units of observation represent the dataset (documents, photos, persons, countries), what kind of information each unit provides or whether there are errors, sources of noise or redundancies in the dataset. Reflect on data that refer to individuals to avoid possible social biases or privacy violations.

- Collection process. It is intended to help researchers and users think about how to create alternative datasets with similar characteristics. It details, for example, how the data were acquired, who was involved in the collection process, or what the ethical review process was like. It deals especially with the ethical aspects of processing data protected by the GDPR.

- Preprocessing, cleansing or tagging. These questions allow data users to determine whether data have been processed in ways that are compatible with their intended uses. Inquire whether any preprocessing, cleansing or tagging of the data was performed, or whether the software that was used to preprocess, cleanse and tag the data is available.

- Uses. This section provides information on those tasks for which the data may or may not be used. For this, questions such as: Has the dataset already been used for any task? What other tasks can it be used for? Does the composition of the dataset or the way it was collected, preprocessed, cleaned and labelled affect other future uses?

- Distribution. This covers how the dataset will be disseminated. Questions focus on whether the data will be distributed to third parties and, if so, how, when, what are the restrictions on use and under what licences.

- Maintenance. The questionnaire ends with questions aimed at planning the maintenance of the data and communicating the plan to the users of the data. For example, answers are given to whether the dataset will be updated or who will provide support.

It is recommended that all questions are considered prior to data collection, so that data creators can be aware of potential problems. To illustrate how each of these questions could be answered in practice, the model developers have produced an appendix with an example for a given dataset.

Is Datasheets for datasets effective?

The Datasheets for datasets data documentation framework has initially received good reviews, but its implementation continues to face challenges, especially when working with dynamic data.

To find out whether the framework effectively addresses the documentation needs of data creators and users, in June 2022, Microsoft USA and the University of Michigan conducted a study on its implementation. To do so, they conducted a series of interviews and a follow-up on the implementation of the questionnaire by a number of machine learning professionals.

In summary, participants expressed the need for documentation frameworks to be adaptable to different contexts, to be integrated into existing tools and workflows, and to be as automated as possible, partly due to the length of the questions. However, they also highlighted its advantages, such as reducing the risk of information loss, promoting collaboration between all those involved in the data lifecycle, facilitating data discovery and fostering critical thinking, among others.

In short, this is a good starting point, but it will have to evolve, especially to adapt to the needs of dynamic data and documentation flows applied in different contexts.

Content prepared by the datos.gob.es team.

When publishing open data, it is essential to ensure its quality. If data is well documented and of the required quality, it will be easier to reuse, as there will be less additional work for cleaning and processing. In addition, poor data quality can be costly for publishers, who may spend more money on fixing errors than on avoiding potential problems in advance.

To help in this task, the Aporta Initiative has developed the "Practical guide for improving the quality of open data", which provides a compendium of guidelines for acting on each of the characteristics that define quality, driving its improvement. The document takes as a reference the data.europe.eu data quality guide, published in 2021 by the Publications Office of the European Union.

Who is the guide aimed at?

The guide is aimed at open data publishers, providing them with clear guidelines on how to improve the quality of their data.

However, this collection can also provide guidance to data re-users on how to address the quality weaknesses that may be present in the datasets they work with.

What does the guide include?

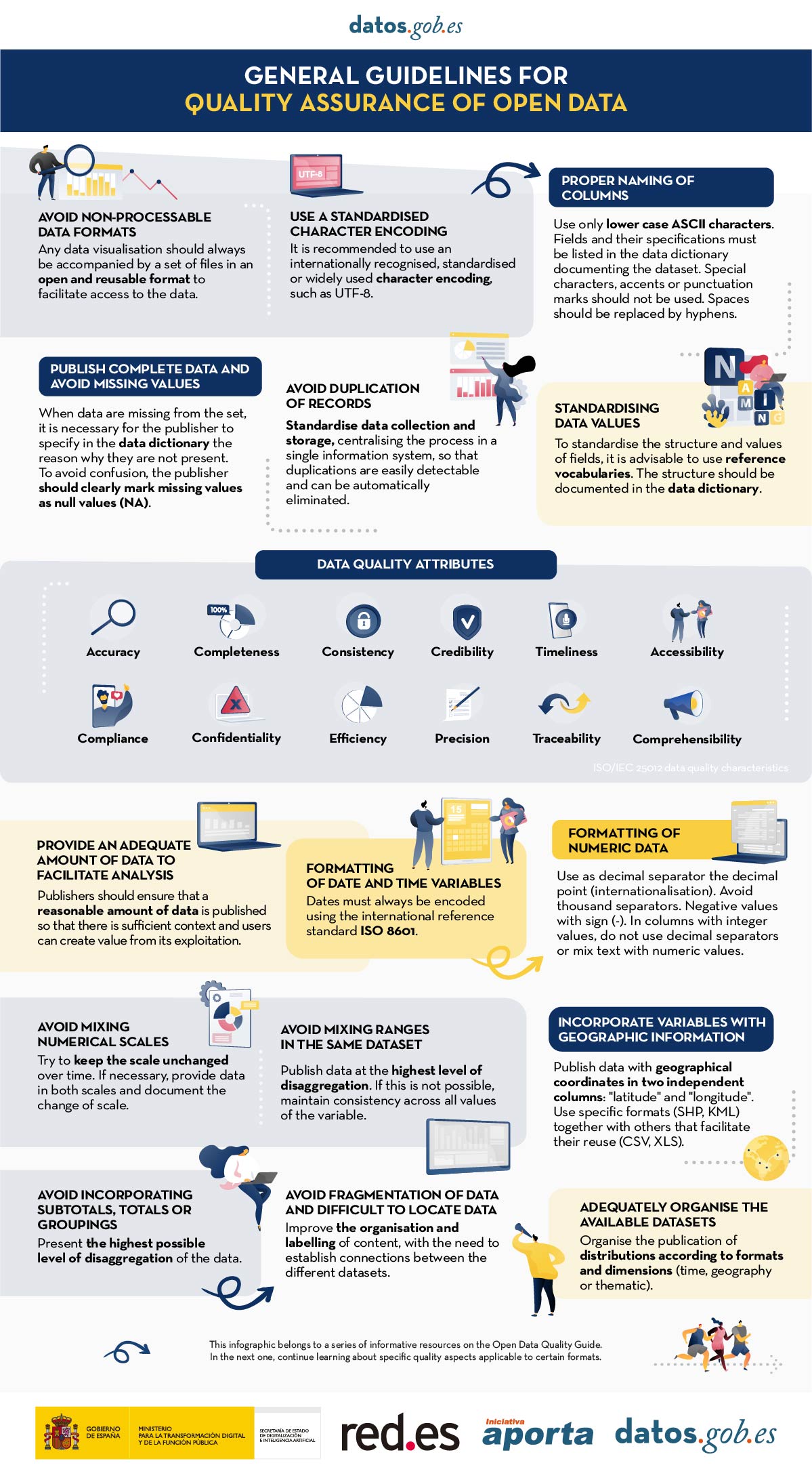

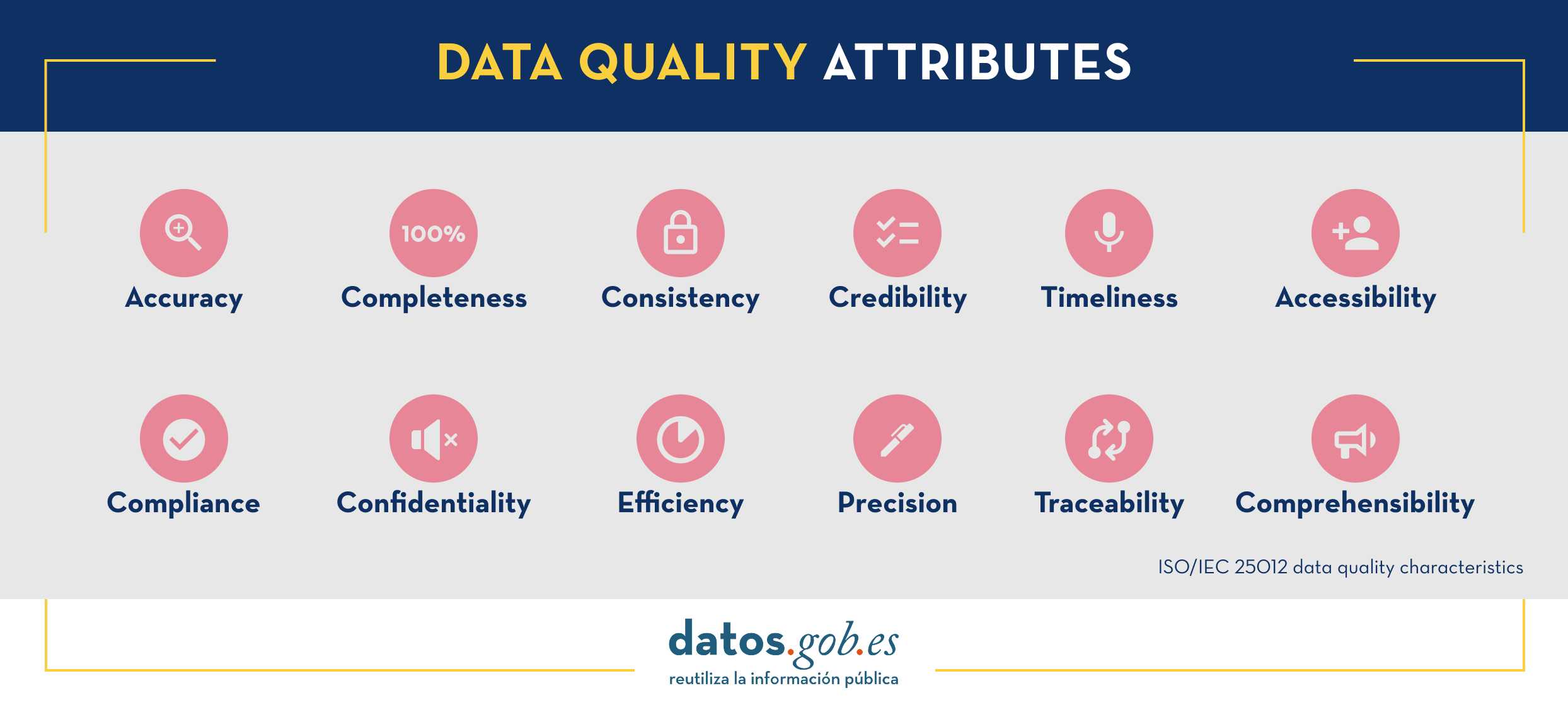

The document begins by defining the characteristics, according to ISO/IEC 25012, that data must meet in order to be considered quality data, which are shown in the following image

Next, the bulk of the guide focuses on the description of recommendations and good practices to avoid the most common problems that usually arise when publishing open data, structured as follows:

- A first part where a series of general guidelines are detailed to guarantee the quality of open data, such as, for example, using a standardised character encoding, avoiding duplicity of records or incorporating variables with geographic information. For each guideline, a detailed description of the problem, the quality characteristics affected and recommendations for their resolution are provided, together with practical examples to facilitate understanding.

- A second part with specific guidelines for ensuring the quality of open data according to the data format used. Specific guidelines are included for CSV, XML, JSON, RDF and APIs.

- Finally, the guide also includes recommendations for data standardisation and enrichment, as well as for data documentation, and a list of useful tools for working on data quality.

You can download the guide here or at the bottom of the page (only available in Spanish).

Additional materials

The guide is accompanied by a series of infographics that compile the above guidelines:

- Infographic "General guidelines for quality assurance of open data".

- Infographic "Guidelines for quality assurance using specific data formats”.

Nowadays we can find a great deal of legislative information on the web. Countries, regions and municipalities make their regulatory and legal texts public through various spaces and official bulletins. The use of this information can be of great use in driving improvements in the sector: from facilitating the location of legal information to the development of chatbots capable of resolving citizens' legal queries.

However, locating, accessing and reusing these documents is often complex, due to differences in legal systems, languages and the different technical systems used to store and manage the data.

To address this challenge, the European Union has a standard for identifying and describing legislation called the European Legislation Identifier (ELI).

What is the European Legislation Identifier?

The ELI emerged in 2012 through Council Conclusions (2012/C 325/02) in which the European Union invited Member States to adopt a standard for the identification and description of legal documents. This initiative has been further developed and enriched by new conclusions published in 2017 (2017/C 441/05) and 2019 (2019/C 360/01).

The ELI, which is based on a voluntary agreement between EU countries, aims to facilitate access, sharing and interconnection of legal information published in national, European and global systems. This facilitates their availability as open datasets, fostering their re-use.

Specifically, the ELI allows:

- Identify legislative documents, such as regulations or legal resources, uniquely by means of a unique identifier (URI), understandable by both humans and machines.

- Define the characteristics of each document through automatically processable metadata. To this end, it uses vocabularies defined by means of ontologies agreed and recommended for each field.

Thanks to this, a series of advantages are achieved:

- It provides higher quality and reliability.

- It increases efficiency in information flows, reducing time and saving costs.

- It optimises and speeds up access to legislation from different legal systems by providing information in a uniform manner.

- It improves the interoperability of legal systems, facilitating cooperation between countries.

- Facilitates the re-use of legal data as a basis for new value-added services and products that improve the efficiency of the sector.

- It boosts transparency and accountability of Member States.

Implementation of the ELI in Spain

The ELI is a flexible system that must be adapted to the peculiarities of each territory. In the case of the Spanish legal system, there are various legal and technical aspects that condition its implementation.

One of the main conditioning factors is the plurality of issuers, with regulations at national, regional and local level, each of which has its own means of official publication. In addition, each body publishes documents in the formats it considers appropriate (pdf, html, xml, etc.) and with different metadata. To this must be added linguistic plurality, whereby each bulletin is published in the official languages concerned.

It was therefore agreed that the implementation of the ELI would be carried out in a coordinated manner by all administrations, within the framework of the Sectoral Commission for e-Government (CSAE), in two phases:

- Due to the complexity of local regulations, in the first phase, it was decided to address only the technical specification applicable to the State and the Autonomous Communities, by agreement of the CSAE of 13 March 2018.

- In February 2022, a new version was drafted to include local regulations in its application.

With this new specification, the common guidelines for the implementation of the ELI in the Spanish context are established, but respecting the particularities of each body. In other words, it only includes the minimum elements necessary to guarantee the interoperability of the legal information published at all levels of administration, but each body is still allowed to maintain its own official journals, databases, internal processes, etc.

With regard to the temporal scope, bodies have to apply these specifications in the following way:

- State regulations: apply to those published from 29/12/1978, as well as those published before if they have a consolidated version.

- Autonomous Community legislation: applies to legislation published on or after 29/12/1978.

- Local regulations: each entity may apply its own criteria.

How to implement the ELI?

The website https://www.elidata.es/ offers technical resources for the application of the identifier. It explains the contextual model and provides different templates to facilitate its implementation:

It also offers the list of common minimum metadata, among other resources.

In addition, to facilitate national coordination and the sharing of experiences, information on the implementation carried out by the different administrations can also be found on the website.

The ELI is already applied, for example, in the Official State Gazette (BOE). From its website it is possible to access all the regulations in the BOE identified with ELI, distinguishing between state and autonomous community regulations. If we take as a reference a regulation such as Royal Decree-Law 24/2021, which transposed several European directives (including the one on open data and reuse of public sector information), we can see that it includes an ELI permalink.

In short, we are faced with a very useful common mechanism to facilitate the interoperability of legal information, which can promote its reuse not only at a national level, but also at a European level, favouring the creation of the European Union's area of freedom, security and justice.

Content prepared by the datos.gob.es team.

A data space is an ecosystem where, on a voluntary basis, the data of its participants (public sector, large and small technology or business companies, individuals, research organizations, etc.) are pooled. Thus, under a context of sovereignty, trust and security, products or services can be shared, consumed and designed from these data spaces.

This is especially important because if the user feels that he has control over his own data, thanks to clear and concise communication about the terms and conditions that will mark its use, the sharing of such data will become effective, thus promoting the economic and social development of the environment.

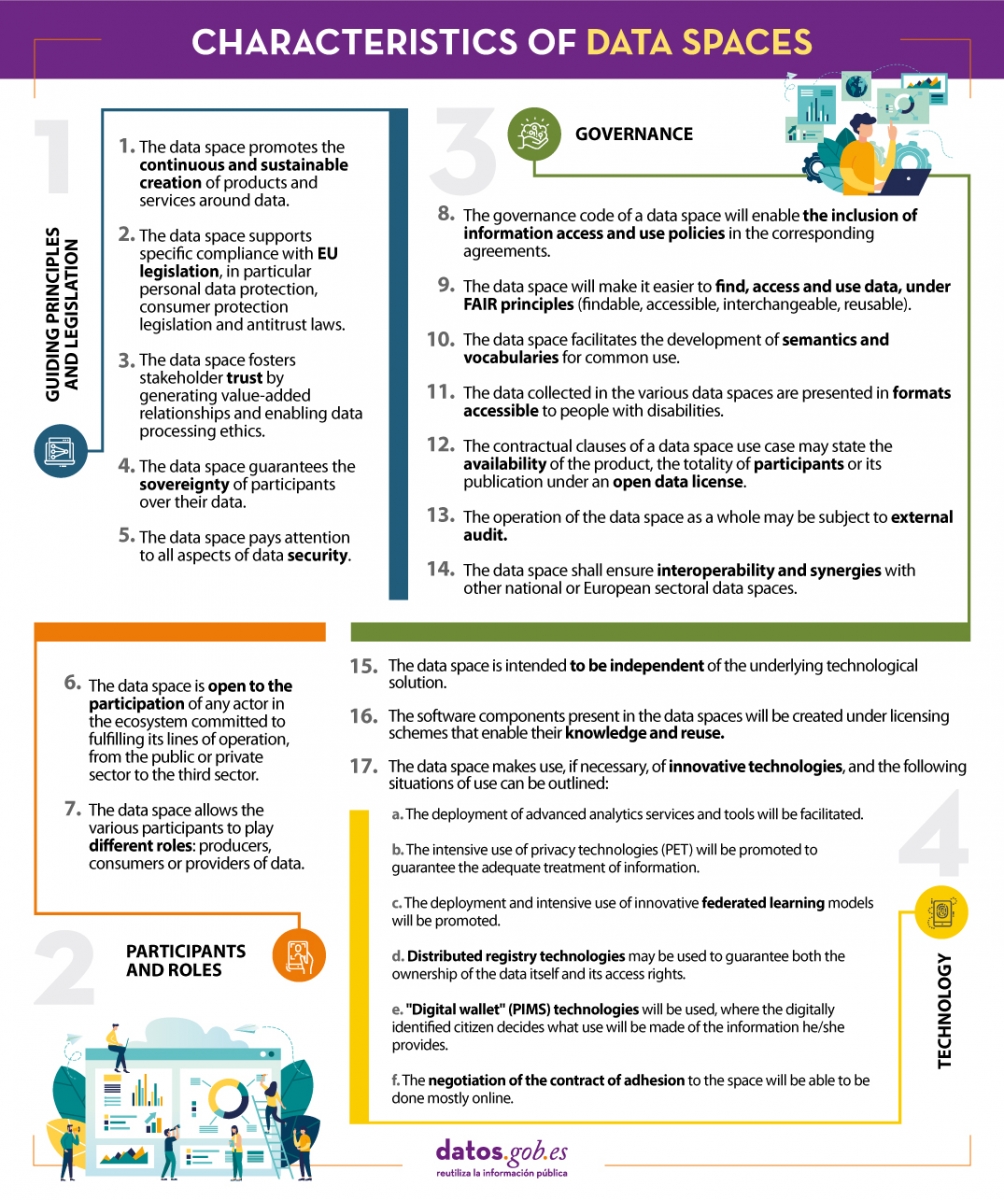

In line with this idea and with the aim of improving the design of data spaces, the Data Office establishes a series of characteristics whose objective is to record the regulations that must be followed to design, from an architectural point of view, efficient and functional data spaces.

We summarize in the following visual some of the most important characteristics for the creation of data spaces. To consult the original document and all the standards proposed by the Data Office, please download the attached document at the end of this article.

(You can download the accessible version in word here)

This report published by the European Data Portal (EDP) aims to advance the debate on the medium and long-term sustainability of open data portal infrastructures.

It provides recommendations to open data publishers and data publishers on how to make open data available and how to promote its reuse. It is based on the previous work done by the data.europa.eu team, on research on open data management, and on the interaction between humans and data.

Considering the conclusions, 10 recommendations are proposed for increasing the reuse of data.

The report is available at this link: " Principles and recommendations to make data.europa.eu data more reusable: A strategy mapping report "

One of the key actions that we recently highlighted as necessary to build the future of open data in our country is the implementation of processes to improve data management and governance. It is no coincidence that proper data management in our organisations is becoming an increasingly complex and in-demand task. Data governance specialists, for example, are increasingly in demand - with more than 45,000 active job openings in the US for a role that was virtually non-existent not so long ago - and dozens of data management platforms now advertise themselves as data governance platforms.

But what's really behind these buzzwords - what is it that we really mean by data governance? In reality, what we are talking about is a series of quite complex transformation processes that affect the whole organisation.

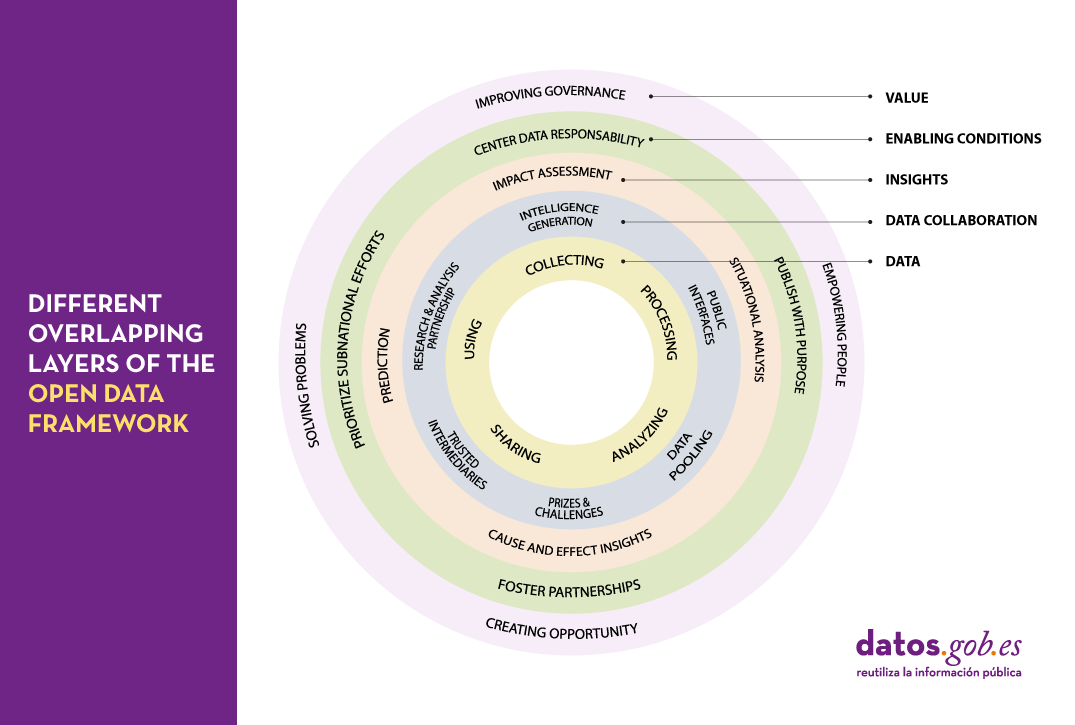

This complexity is perfectly reflected in the framework proposed by the Open Data Policy Lab, where we can clearly see the different overlapping layers of the model and what their main characteristics are - leading to a journey through the elaboration of data, collaboration with data as the main tool, knowledge generation, the establishment of the necessary enabling conditions and the creation of added value.

Let's now peel the onion and take a closer look at what we will find in each of these layers:

The data lifecycle

We should never consider data as isolated elements, but as part of a larger ecosystem, which is embedded in a continuous cycle with the following phases:

- Collection or collation of data from different sources.

- Processing and transformation of data to make it usable.

- Sharing and exchange of data between different members of the organisation.

- Analysis to extract the knowledge being sought.

- Using data according to the knowledge obtained.

Collaboration through data

It is not uncommon for the life cycle of data to take place solely within the organisation where it originates. However, we can increase the value of that data exponentially, simply by exposing it to collaboration with other organisations through a variety of mechanisms, thus adding a new layer of management:

- Public interfaces that provide selective access to data, enabling new uses and functions.

- Trusted intermediaries that function as independent data brokers. These brokers coordinate the use of data by third parties, ensuring its security and integrity at all times.

- Data pooling that provide a common, joint, complete and coherent view of data by aggregating portions from different sources.

- Research and analysis partnership, granting access to certain data for the purpose of generating specific knowledge.

- Prizes and challenges that give access to specific data for a limited period of time to promote new innovative uses of data.

- Intelligence generation, whereby the knowledge acquired by the organisation through the data is also shared and not just the raw material.

Insight generation

Thanks to the collaborations established in the previous layer, it will be possible to carry out new studies of the data that will allow us both to analyse the past and to try to extrapolate the future using various techniques such as:

- Situational analysis, knowing what is happening in the data environment.

- Cause and effect insigths, looking for an explanation of the origin of what is happening.

- Prediction, trying to infer what will happen next.

- Impact assessment, establishing what we expect should happen.

Enabling conditions

There are a number of procedures that when applied on top of an existing collaborative data ecosystem can lead to even more effective use of data through techniques such as:

- Publish with a purpose, with the aim of coordinating data supply and demand as efficiently as possible.

- Foster partnerships, including in our analysis those groups of people and organisations that can help us better understand real needs.

- Prioritize subnational efforts, strengthening of alternative data sources by providing the necessary resources to create new data sources in untapped areas.

- Center data responsability, establishing an accountability framework around data that takes into account the principles of fairness, engagement and transparency.

Value generation

Scaling up the ecosystem -and establishing the right conditions for that ecosystem to flourish- can lead to data economies of scale from which we can derive new benefits such as:

- Improving governance and operations of the organisation itself through the overall improvements in transparency and efficiency that accompany openness processes.

- Empowering people by providing them with the tools they need to perform their tasks in the most appropriate way and make the right decisions.

- Creating new opportunities for innovation, the creation of new business models and evidence-led policy making.

- Solving problems by optimising processes and services and interventions within the system in which we operate.

As we can see, the concept of data governance is actually much broader and more complex than one might initially expect and encompasses a number of key actions and tasks that in most organisations it will be practically impossible to try to centralise in a single role or through a single tool. Therefore, when establishing a data governance system in an organisation, we should face the challenge as an integral transformation process or a paradigm shift in which practically all members of the organisation should be involved to a greater or lesser extent. A good way to face this challenge with greater ease and better guarantees would be through the adoption and implementation of some of the frameworks and reference standards that have been created in this respect and that correspond to different parts of this model.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation.

The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.