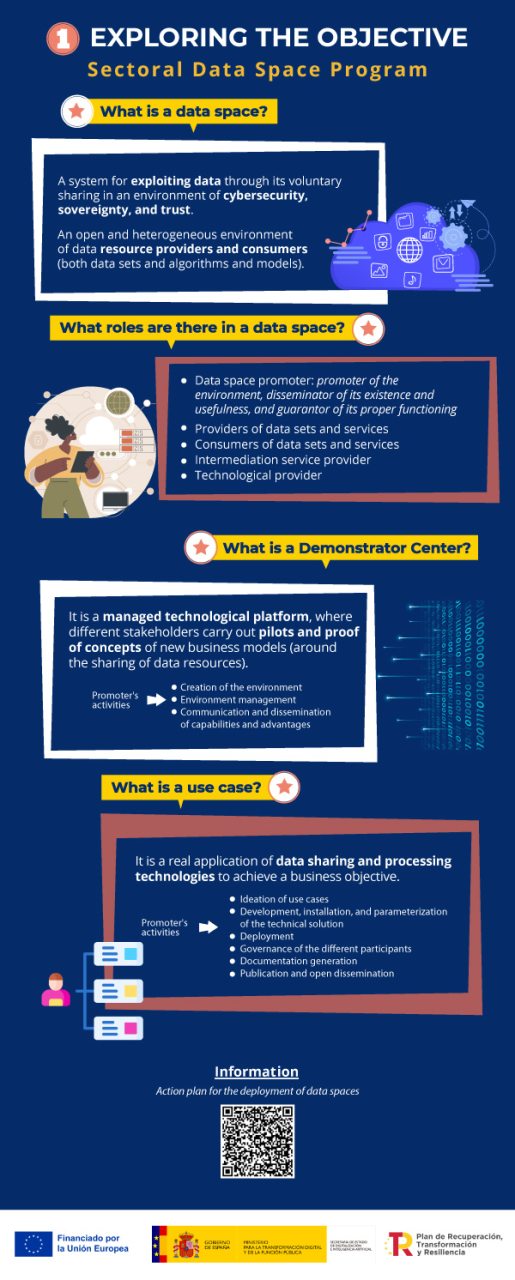

The strong commitment to common data spaces at European level is one of the main axes of the European Data Strategy adopted in 2020. This approach was already announced in that document as a basis, on the one hand, to support public policy momentum and, on the other hand, to facilitate the development of innovative products and services based on data intelligence and machine learning.

However, the availability of large sectoral datasets required, as an unavoidable prerequisite, an appropriate cross-cutting regulatory framework to establish the conditions for feasibility and security from a legal perspective. In this regard, once the reform of the regulation on the re-use of public sector information had been consolidated, with major innovations such as high-value data, the regulation on data governance was approved in 2022 and then, in 2023, the so-called Data Act. With these initiatives already approved and the recent official publication of the Artificial Intelligence Regulation, the promotion of data spaces is of particular importance, especially in the public sector, in order to ensure the availability of sufficient and quality data.

Data spaces: diversity in their configuration and regulation

The European Data Strategy already envisaged the creation of common European data spaces in a number of sectors and areas of public interest, but at the same time did not rule out the launching of new ones. In fact, in recent years, new spaces have been announced, so that the current number has increased significantly, as we shall see below.

The main reason for data spaces is to facilitate the sharing and exchange of reliable and secure data in strategic economic sectors and areas of public interest. Thus, it is not simply a matter of promoting large datasets but, above all, of supporting initiatives that offer data accessibility according to suitable governance models that, ultimately, allow the interoperability of data throughout the European Union on the basis of appropriate technological infrastructures.

Although general characterisations of data spaces can be offered on the basis of a number of common notes, there is a great diversity from a legal perspective in terms of the purposes they pursue, the conditions under which data are shared and, in particular, the subjects involved.

This heterogeneity is also present in spaces related to the public sector, i.e. those in which there is a prominent role for data generated by administrations and other public entities in the exercise of their functions, to which, therefore, the regulation on reuse and open data approved in 2019 is fully applicable.

Which are the European public sector data spaces?

In early 2024, the second version of a European Commission working document was published with the dual objective of providing an updated overview of the European policy framework for data spaces and also identifying European data space initiatives to assess their maturity and the main challenges ahead for each of them.

In particular, as far as public administrations are concerned, four data spaces are envisaged: the legal data space, the public procurement data space, the data space linked to the technical "once only" system in the context of eGovernment and, finally, the security data space for innovation. These are very diverse initiatives which, moreover, present an uneven degree of maturity, so that some have an advanced level of development and solid institutional support, while other cases are only initially sketched out and have considerable effort ahead for their design and implementation.

Let us take a closer look at each of these spaces referred to in the working paper.

1. Legal data space

It is a data space linked to legislation and jurisprudence generated by both the European Union and the Member States. The aim of this initiative is to support the legal professions, public administrations and, in general, to facilitate access to society in order to strengthen the mechanisms of the rule of law. This space has so far been based on two specific initiatives:

- One concerning information on officially published legislation, which has been articulated through the European Legislation Identifier-ELI. It is a European standard that facilitates the identification of rules in a stable and easily reusable way as it describes legislation with a set of automatically processable metadata, according to a recommended ontology.

- The second concerns decisions taken by judicial bodies, which are made accessible through an European system of unique identifiers called ECLI (European Case Law Identifier) that is assigned to the decisions of both European and national judicial bodies.

These two important initiatives, which facilitate access to and automated processing of legal information, have required a shift from a document-based management model (official gazette, court decisions) to a data-based model. And it is precisely this paradigm shift that has made it possible to offer advanced information services that go beyond the legal and linguistic limits posed by regulatory and linguistic diversity across the European Union.

In any case, while recognising the important progress they represent, there are still important challenges to be faced, such as facilitating access by specific precepts and not by normative documents or, among others, the availability of judicial documents on the basis of the rules they apply and, also, the linking of the rules with their judicial interpretation by the various judicial bodies in all States. In the case of the latter two scenarios, the challenge is even greater, as they would require the automated linking of both identifiers.

2. Public procurement data space

This is undoubtedly one of the areas with the greatest potential impact, given that in the European Union as a whole, it is estimated that public entities spend around two trillion euros (almost 14% of GDP) on the purchase of services, works and supplies. This space is therefore intended not only to facilitate access to the public procurement market across the European Union but also to strengthen transparency and accountability in public procurement spending, which is essential in the fight against corruption and in improving efficiency.

The practical relevance of this space is reinforced by the fact that it has a specific official document that strongly supports the project and sets out a precise roadmap with the objective of ensuring its deployment within a reasonable timeframe. Moreover, despite limitations in its scope of application (there is no provision for extending the publication obligation to contracts below the thresholds set at European level, nor for contract completion notices), it is at a very advanced stage, in particular as regards the availability of a specific ontology which facilitates the accessibility of information and its re-use by reinforcing the conditions for interoperability.

In short, this space is facilitating the automated processing of public procurement data by interconnecting existing datasets, thus providing a more complete picture of public procurement in the European Union as a whole, even though it has been estimated that there are more than 250,000 contracting authorities awarding public contracts.

3. Single Technical System (e-Government)

This new space is intended to support the need that exists in administrative procedures to collect information issued by the administrations of other States, without the interested parties being required to do so directly. It is therefore a matter of automatically and securely gathering the required evidence in a formalised environment based on the direct interconnection between the various public bodies, which will thus act as authentic sources of the required information.

This initiative is linked to the objective of addressing administrative simplification and, in particular, to the implementation of:

- Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2022/1463 of 5 August 2022 laying down the technical and operational specifications of the technical system for the automated cross-border exchange of evidence and the implementation of the "only once" principle.

- Regulation (EU) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 March 2024 laying down measures to ensure a high level of public sector interoperability throughout the Union (the Interoperable Europe Regulation), which aims to establish a robust governance structure for interoperability in the public sector.

4. Security data space for innovation

The objective here is to improve law enforcement authorities' access to the data needed to train and validate algorithms with the aim of enhancing the use of artificial intelligence and thus strengthening law enforcement in full respect of ethical and legal standards.

While there is a clear need to facilitate the exchange of data between Member States' law enforcement authorities, the working paper emphasises that this is not a priority for AI strategies in this area, and that the advanced use of data in this area from an innovation perspective is currently relatively low.

In this respect, it is appropriate to highlight the initiative for the development of the Europol sandbox, a project that was sponsored by the decision of the Standing Committee on Operational Cooperation on Internal Security (COSI) to create an isolated space that allows States to develop, train and validate artificial intelligence and machine learning models.

Now that the process of digitisation of public entities is largely consolidated, the main challenge for data spaces in this area is to provide adequate technical, legal and organisational conditions to facilitate data availability and interoperability. In this sense, these data spaces should be taken into account when expanding the list of high-value data, along the lines already advanced by the study published by the European Commission in 2023, which emphasises that the data ets with the greatest potential are those related to government and public administration, justice and legal matters, as well as financial data.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the "Innovation, Law and Technology" Research Group (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

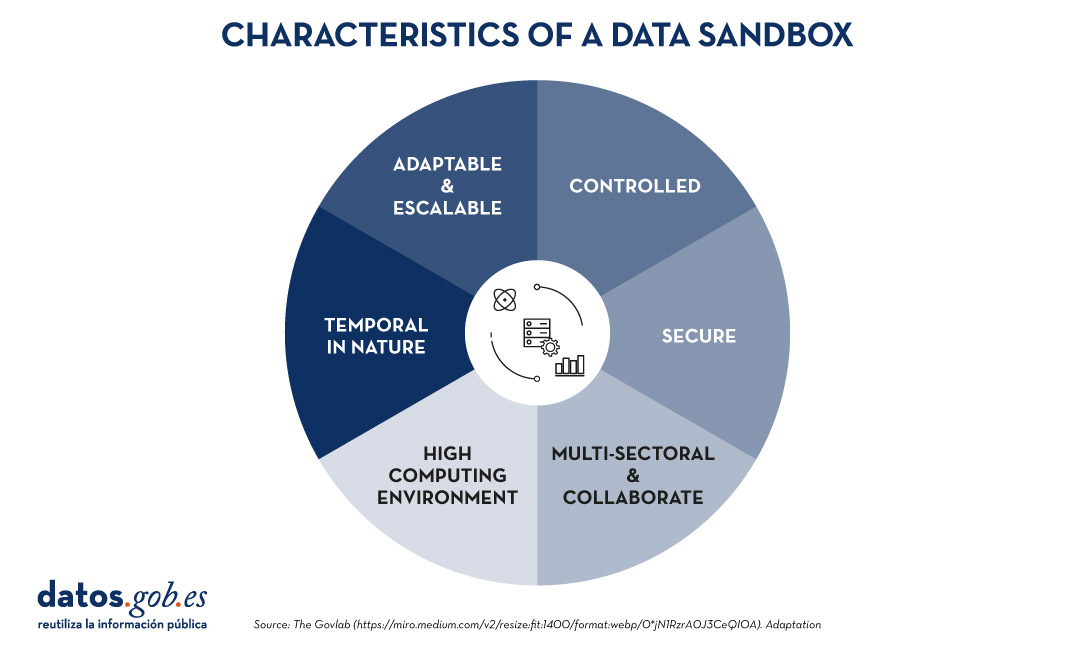

Data sandboxes are tools that provide us with environments to test new data-related practices and technologies, making them powerful instruments for managing and using data securely and effectively. These spaces are very useful in determining whether and under what conditions it is feasible to open the data. Some of the benefits they offer are:

- Controlled and secure environments: provide a workspace where information can be explored and its usefulness and quality assessed before committing to wider sharing. This is particularly important in sensitive sectors, where privacy and data security are paramount.

- Innovation: they provide a safe space for experimentation and rapid prototyping, allowing for rapid iteration, testing and refining new ideas and data-driven solutions as test bench before launching them to the public.

- Multi-sectoral collaboration: facilitate collaboration between diverse actors, including government entities, private companies, academia and civil society. This multi-sectoral approach helps to break down data silos and promotes the sharing of knowledge and good practices across sectors.

- Adaptive and scalable use: they can be adjusted to suit different data types, use cases and sectors, making them a versatile tool for a variety of data-driven initiatives.

- Cross-border data exchange: they provide a viable solution to manage the challenges of data exchange between different jurisdictions, especially with regard to international privacy regulations.

The report "Data Sandboxes: Managing the Open Data Spectrum" explores the concept of data sandboxes as a tool to strike the right balance between the benefits of open data and the need to protect sensitive information.

Value proposition for innovation

In addition to all the benefits outlined above, data sandboxes also offer a strong value proposition for organisations looking to innovate responsibly. These environments help us to improve data quality by making it easier for users to identify inconsistencies so that improvements can be made. They also contribute to reducing risks by providing secure environments to enable work with sensitive data. By fostering cross-disciplinary experimentation, collaboration and innovation, they contribute to increasing the usability of data and developing a data-driven culture within organisations. In addition, data sandboxes help reduce barriers to data access , improving transparency and accountability, which strengthens citizens' trust and leads to an expansion of data exchanges.

Types of data sandboxes and characteristics

Depending on the main objective when implementing a sandbox, there are three different types of sandboxes:

- Regulatory sandboxes, which allow companies and organisations to test innovative services under the close supervision of regulators in a specific sector or area.

- Innovation sandboxes, which are frequently used by developers to test new features and get quick feedback on their work.

- Research sandboxes, which make it easier for academia and industry to safely test new algorithms or models by focusing on the objective of their tests, without having to worry about breaching established regulations.

In any case, regardless of the type of sandbox we are working with, they are all characterised by the following common key aspects:

Figure 1. Characteristics of a data sandbox. Adaptation of a visual of The Govlab.

Each of these is described below:

- Controlled: these are restricted environments where sensitive and analysed data can be accessed securely, ensuring compliance with relevant regulations.

- Secure: they protect the privacy and security of data, often using anonymised or synthetic data.

- Collaborative: facilitating collaboration between different regions, sectors and roles, strengthening data ecosystems.

- High computational capacity: provide advanced computational resources capable of performing complex tasks on the data when needed.

- Temporal in nature: They are designed for temporary use and with a short life cycle, allowing for rapid and focused experimentation that either concludes once its objective is achieved or becomes a new long-term project.

- Adaptable: They are flexible enough to customise and scale according to needs and different data types, use cases and contexts.

Examples of data sandboxes

Data sandboxes have long been successfully implemented in multiple sectors across Europe and around the world, so we can easily find several examples of their implementation on our continent:

- Data science lab in Denmark: it provides access to sensitive administrative data useful for research, fostering innovation under strict data governance policies.

- TravelTech in Lithuania: an open access sandbox that provides tourism data to improve business and workforce development in the sector.

- INDIGO Open Data Sandbox: it promotes data sharing across sectors to improve social policies, with a focus on creating a secure environment for bilateral data sharing initiatives.

- Health data science sandbox in Denmark: a training platform for researchers to practice data analysis using synthetic biomedical data without having to worry about strict regulation.

Future direction and challenges

As we have seen, data sandboxes can be a powerful tool for fostering open data, innovation and collaboration, while ensuring data privacy and security. By providing a controlled environment for experimentation with data, they enable all interested parties to explore new applications and knowledge in a reliable and safe way. Sandboxes can therefore help overcome initial barriers to data access and contribute to fostering a more informed and purposeful use of data, thus promoting the use of data-driven solutions to public policy problems.

However, despite their many benefits, data sandboxes also present a number of implementation challenges. The main problems we might encounter in implementing them include:

- Relevance: ensure that the sandbox contains high quality and relevant data, and that it is kept up to date.

- Governance: establish clear rules and protocols for data access, use and sharing, as well as monitoring and compliance mechanisms.

- Scalability: successfully export the solutions developed within the sandbox and be able to translate them into practical applications in the real world.

- Risk management: address comprehensively all risks associated with the re-use of data throughout its lifecycle and without compromising its integrity.

However, as technologies and policies continue to evolve, it is clear that data sandboxes are set to be a useful tool and play an important role in managing the spectrum of data openness, thereby driving the use of data to solve increasingly complex problems. Furthermore, the future of data sandboxes will be influenced by new regulatory frameworks (such as Data Regulations and Data Governance) that reinforce data security and promote data reuse, and by integration with privacy preservation and privacy enhancing technologies that allow us to use data without exposing any sensitive information. Together, these trends will drive more secure data innovation within the environments provided by data sandboxes.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation. The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

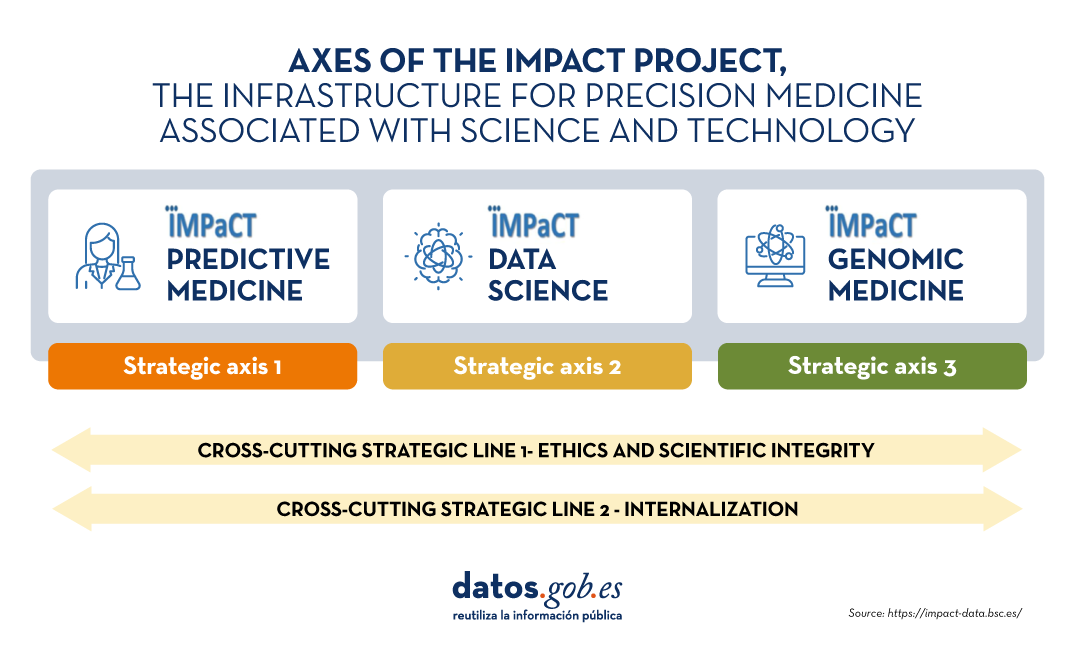

IMPaCT, the Infrastructure for Precision Medicine associated with Science and Technology, is an innovative programme that aims to revolutionise medical care. Coordinated and funded by the Carlos III Health Institute, it aims to boost the effective deployment of personalised precision medicine.

Personalised medicine is a medical approach that recognises that each patient is unique. By analysing the genetic, physiological and lifestyle characteristics of each person, more efficient and safer tailor-made treatments with fewer side effects are developed. Access to this information is also key to making progress in prevention and early detection, as well as in research and medical advances.

IMPaCT consists of 3 strategic axes:

- Axis 1 Predictive medicine: COHORTE Programme. It is an epidemiological research project consisting of the development and implementation of a structure for the recruitment of 200,000 people to participate in a prospective study.

- Strand 2 Data science: DATA Programme. It is a programme focused on the development of a common, interoperable and integrated system for the collection and analysis of clinical and molecular data. It develops criteria, techniques and best practices for the collection of information from electronic medical records, medical images and genomic data.

- Axis 3 Genomic medicine: GENOMICS Programme. It is a cooperative infrastructure for the diagnosis of rare and genetic diseases. Among other issues, it develops standardised procedures for the correct development of genomic analyses and the management of the data obtained, as well as for the standardisation and homogenisation of the information and criteria used.

In addition to these axes, there are two transversal strategic lines: one focused on ethics and scientific integrity and the other on internationalisation, as summarised in the following visual.

Source: IMPaCT-Data

In the following, we will focus on the functioning and results of IMPaCT-Data, the project linked to axis 2.

IMPaCT-Data, an integrated environment for interoperable data analysis

IMPaCT-Data is oriented towards the development and validation of an environment for the integration and joint analysis of clinical, molecular and genetic data, for secondary use, with the ultimate goal of facilitating the effective and coordinated implementation of personalised precision medicine in the National Health System. It is currently made up of a consortium of 45 entities associated by an agreement that runs until 31 December 2025.

Through this programme, the aim is to create a cloud infrastructure for medical data for research, as well as the necessary protocols to coordinate, integrate, manage and analyse such data. To this end, a roadmap with the following technical objectives is followed:

Source: IMPaCT-Data.

Results of IMPaCT-Data

As we can see, this infrastructure, still under development, will provide a virtual research environment for data analysis through a variety of services and products:

- IMPaCT-Data Federated Cloud. It includes access to public and access-controlled data, as well as tools and workflows for the analysis of genomic data, medical records and images. At this video shows how federated user access and job execution is realised through the use of shared computational resources. This allows for viewing and accessing the results in HTML and raw format, as well as their metadata. For those who want to go deeper into the user access options, please see this video another video where the linking of institutional accounts to the IMPaCT-Data account and the use of passports and visas for local access to protected data is shown.

- Compilation of software tools for the analysis of IMPaCT-Data. These tools are publicly accessible through the iMPaCT-Data domain domain at bio.tools a registry of software components and databases aimed at researchers in the field of biological and biomedical sciences. It includes a wide range of tools. On the one hand, we find general solutions, for example, focused on privacy through actions related to data de-identification and anonymisation (FAIR4Health Data Privacy Tool). On the other hand, there are specific tools, focused on very specific issues, such as gene expression meta-analysis (ImaGEO).

- Guidelines with recommendations and good practices for the collection of medical information. There are currently three guides available: "IMPaCT-Data recommendations on data and software", "IMPaCT-Data additional considerations to the IMPaCT 2022 call for projects" and "IMPaCT-Data recommendations on data and software" .

In addition to these, there are a number of deliverables related to technical aspects of the project, such as comparisons of techniques or proofs of concept, as well as scientific publications.

Driving use cases through demonstrators

One of the objectives of IMPaCT-Data is to contribute to the evaluation of technologies associated with the project's developments, through an ecosystem of demonstrators. The aim is to encourage contributions from companies, organisations and academic groups to drive improvements and achieve large-scale implementation of the project.

To meet this objective, different activities are organised where specific components are evaluated in collaboration with members of IMPaCT-Data. One example is the oRBITS terminology server for the encoding of clinical phenotypes into HPO (Human Phenotype Ontology) aimed at automatically extracting and encoding information contained in unstructured clinical reports using natural language processing. It uses the HPO terminology, which aims to standardise the collection of phenotypic data, making it accessible for further analysis.

Another example of demonstrators refers to the sharing of virtualised medical data between different centres for research projects, within a governed, efficient and secure environment, where all data quality standards defined by each entity are met within a governed, efficient and secure environment, where all data quality standards defined by each entity are met.

A strategic project aligned with Europe

IMPaCT-Data fits directly into the National Strategy for the Secondary Use of National Health System Data, as described in the PERTE on health (Strategic Projects for Economic Recovery and Transformation), with its knowledge, experience and input being of great value for the development of the National Health Data Space.

Furthermore, IMPaCT-Data's developments are directly aligned with the guidelines proposed by GAIA-X both at a general level and in the specific health environment.

The impact of the project in Europe is also evidenced by its participation in the european project GDI (Genomic Data Infrastructure) which aims to facilitate access to genomic, phenotypic and clinical data across Europe, where IMPaCT-Data is being used as a tool at national level.

This shows that thanks to IMPaCT-Data it will be possible to promote biomedical research projects not only in Spain, but also in Europe, thus contributing to the improvement of public health and individualised treatment of patients.

One of the main objectives of Regulation (EU) of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 December 2023 on harmonised rules for fair access to and use of data (Data Regulation) is to promote the development of interoperability criteria for data spaces, data processing services and smart contracts. In this respect, the Regulation understands interoperability as:

The ability of two or more data spaces or communication networks, systems, connected products, applications, data processing services or components to exchange and use data to perform their functions.

It explicitly states that 'interoperable and high quality data from different domains increase competitiveness and innovationand ensure sustainable economic growth', which requires that 'the same data can be used and reused for different purposes and in an unlimited way, without loss of quality or quantity'. It therefore believes that "a regulatory approach to interoperability that is ambitious and inspires innovation is essential toovercome the dependence on a single provider, which hinders competition and the development of new services".

Interoperability and data spaces

This concern already existed in the European Data Strategy where interoperability was seen as a key element for the valorisation of data and, in particular, for the deployment of Artificial Intelligence. In fact, interoperability is an unavoidable premise for data spaces, so that the establishment of appropriate protocols becomes essential to ensure their potential, both for each of the data spaces internally and also in order to facilitate a cross-cutting integration of several of them.

In this sense, there are frequent standardisation initiatives and meetings to try to establish specific interoperability conditions in this type of scenario, characterised by the diversity of data sources. Although this is an added difficulty, a cross-cutting approach, integrating several data spaces, provides a greater impact on the generation of value-added services and creates the right legal conditions for innovation.

According to the Data Regulation, those who participate in data spaces and offer data or data services to other actors involved in data spaces have to comply with a number of requirements aimed precisely at ensuring appropriate conditions for interoperability and thus that data can be processed jointly. To this end, a description of the content, structure, format and other conditions of use of the data shall be provided in such a way as to facilitate access to and sharing of the data in an automated manner, including in real time or allowing bulk downloading where appropriate.

It should be noted that compliance with technical and semantic standards for interoperability is essential for data spaces, since a minimum standardisation of legal conditions greatly facilitates their operation. In particular, it is of great importance to ensure that the data provider holds the necessary rights to share the data in such an environment and to be able to prove this in an automated way

Interoperability in data processing services

The Data Regulation pays particular attention to the need to improve interoperability between different data processing service providers, so that customers can benefit from the interaction between each of them, thereby reducing dependency on individual providers.

To this end, firstly, it reinforces the reporting obligations of providers of this type of services, to which must be added those derived from the general regulation on the provision of digital content and services general regulation on the provision of digital content and services. In particular, they must be in writing:

- Contractual conditions relating to customer rights, especially in situations related to a possible switch to another provider or infrastructure.

- A full indication of the data that may be exported during the switching process, so that the scope of the interoperability obligation will have to be fixed in advance. In addition, such information has to be made available through an up-to-date online registry to be offered by the service provider.

The Regulation aims to ensure that customers' right to free choice of data service provider is not affected by barriers and difficulties arising from lack of interoperability. The regulation even contemplates an obligation of proactivity so that the change of provider takes place without incidents in the provision of the service to the customer, obliging them to adopt reasonable measures to ensure "functional equivalence" and even to offer free of charge open interfaces to facilitate this process. However, in some cases - in particular where two services are intended to be used in parallel - the former provider is allowed to pass on certain costs that may have been incurred.

Ultimately, the interoperability of data processing services goes beyond simple technical or semantic aspects, so that it becomes an unavoidable premise for ensuring the portability of digital assets, guaranteeing the security and integrity of services and, among other objectives, not interfering with the incorporation of technological innovations, all with a marked prominence of cloud services.

Smart contracts and interoperability

The Data Regulation also pays particular attention to the interoperability conditions allowing the automated execution of data exchanges, for which it is essential to set them in a predetermined way. Otherwise, the optimal operating conditions required by the digital environment, especially from the point of view of efficiency, would be affected.

The new regulation includes specific obligations for smart contract providers and also for those who deploy smart contract tools in the course of their commercial, business or professional activity. For this purpose, a smart contract is defined as a contract that

a computer programme used for the automated execution of an agreement or part thereof, which uses a sequence of electronic data records and ensures their completeness and the accuracy of their chronological order

They have to ensure that smart contracts comply with the obligations of the Regulation as regards the provision of data and, among other aspects, it will be essential to ensure "consistency with the terms of the data sharing agreement that executes the smart contract". They shall therefore be responsible for the effective fulfilment of these requirements by carrying out a conformity assessment and issuing a declaration of compliance with these requirements.

To facilitate the enforcement of these safeguards, the Regulation provides for a presumption of compliance where harmonised standards published in the Official Journal of the European Union are respected the Commission is authorised to request European standardisation organisations to draw up specific provisions.

In the last five years, and in particular since the 2020 Strategy, there has been significant progress in European regulation, which makes it possible to state that the right legal conditions are in place to ensure the availability of quality data to drive technological innovation. As far as interoperability is concerned, very important steps have already been taken, especially in the public sector public sector where we can find disruptive technologies that can be extremely useful. However, the challenge of precisely specifying the scope of the legally established obligations still remains.

For this reason, the Data Regulation itself empowers the Commission toadopt common specifications to ensure effective compliance with the measures it envisages if necessary. However, this is a subsidiary measure, as other avenues to achieve interoperability, such as the development of harmonised standards through standardisation organisations, must be pursued first.

In short, regulating interoperability requires an ambitious approach, as recognised by the Data Regulation itself, although it is a complex process that requires implementing measures at different levels that go beyond the simple adoption of legal rules, even if such legislation represents an important step forward to boost innovation under the right conditions, i.e. beyond simple technological premises.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec). The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

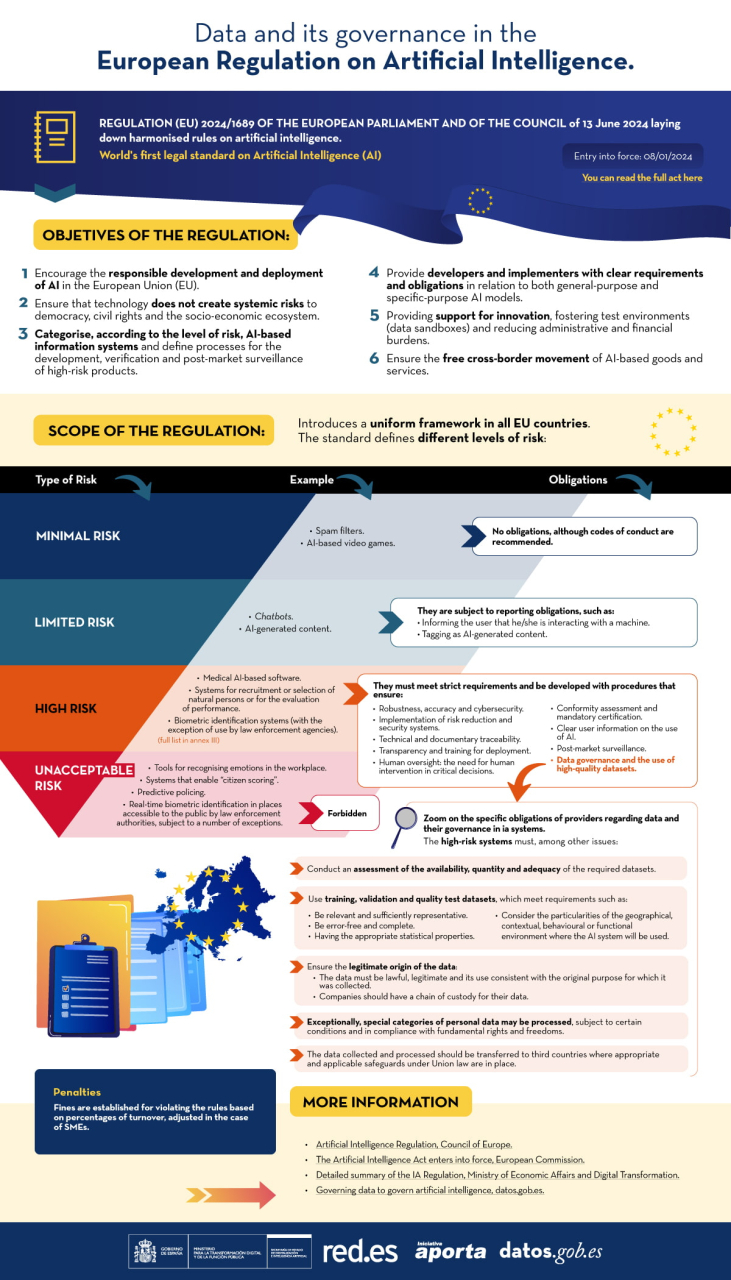

The publication on Friday 12 July 2024 of the Artificial Intelligence Regulation (AIA) opens a new stage in the European and global regulatory framework. The standard is characterised by an attempt to combine two souls. On the one hand, it is about ensuring that technology does not create systemic risks for democracy, the guarantee of our rights and the socio-economic ecosystem as a whole. On the other hand, a targeted approach to product development is sought in order to meet the high standards of reliability, safety and regulatory compliance defined by the European Union.

Scope of application of the standard

The standard allows differentiation between low-and medium-risk systems, high-risk systems and general-purpose AI models. In order to qualify systems, the AIA defines criteria related to the sector regulated by the European Union (Annex I) and defines the content and scope of those systems which by their nature and purpose could generate risks (Annex III). The models are highly dependent on the volume of data, their capacities and operational load.

AIA only affects the latter two cases: high-risk systems and general-purpose AI models. High-risk systems require conformity assessment through notified bodies. These are entities to which evidence is submitted that the development complies with the AIA. In this respect, the models are subject to control formulas by the Commission that ensure the prevention of systemic risks. However, this is a flexible regulatory framework that favours research by relaxing its application in experimental environments, as well as through the deployment of sandboxes for development.

The standard sets out a series of "requirements for high-risk AI systems" (section two of chapter three) which should constitute a reference framework for the development of any system and inspire codes of good practice, technical standards and certification schemes. In this respect, Article 10 on "data and data governance" plays a central role. It provides very precise indications on the design conditions for AI systems, particularly when they involve the processing of personal data or when they are projected on natural persons.

This governance should be considered by those providing the basic infrastructure and/or datasets, managing data spaces or so-called Digital Innovation Hubs, offering support services. In our ecosystem, characterised by a high prevalence of SMEs and/or research teams, data governance is projected on the quality, security and reliability of their actions and results. It is therefore necessary to ensure the values that AIA imposes on training, validation and test datasets in high-risk systems, and, where appropriate, when techniques involving the training of AI models are employed.

These values can be aligned with the principles of Article 5 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and enrich and complement them. To these are added the risk approach and data protection by design and by default. Relating one to the other is ancertainly interesting exercise.

Ensure the legitimate origin of the data. Loyalty and lawfulness

Alongside the common reference to the value chain associated with data, reference should be made to a 'chain of custody' to ensure the legality of data collection processes. The origin of the data, particularly in the case of personal data, must be lawful, legitimate and its use consistent with the original purpose of its collection. A proper cataloguing of the datasets at source is therefore indispensable to ensure a correct description of their legitimacy and conditions of use.

This is an issue that concerns open data environments, data access bodies and services detailed in the Data Governance Regulation (DGA ) or the European Health Data Space (EHDS) and is sure to inspire future regulations. It is usual to combine external data sources with the information managed by the SME.

Data minimisation, accuracy and purpose limitation

AIA mandates, on the one hand, an assessment of the availability, quantity and adequacy of the required datasets. On the other hand, it requires that the training, validation and test datasets are relevant, sufficiently representative and possess adequate statistical properties. This task is highly relevant to the rights of individuals or groups affected by the system. In addition, they shall, to the greatest extent possible, be error-free and complete in view of their intended purpose. AIA predicates these properties for each dataset individually or for a combination of datasets.

In order to achieve these objectives, it is necessary to ensure that appropriate techniques are deployed:

- Perform appropriate processing operations for data preparation, such as annotation, tagging, cleansing, updating, enrichment and aggregation.

- Make assumptions, in particular with regard to the information that the data are supposed to measure and represent. Or, to put it more colloquially, to define use cases.

- Take into account, to the extent necessary for the intended purpose, the particular characteristics or elements of the specific geographical, contextual, behavioural or functional environment in which the high-risk AI system is intended to be used.

Managing risk: avoiding bias

In the area of data governance, a key role is attributed to the avoidance of bias where it may lead to risks to the health and safety of individuals, adversely affect fundamental rights or give rise to discrimination prohibited by Union law, in particular where data outputs influence incoming information for future operations. To this end, appropriate measures should be taken to detect, prevent and mitigate possible biases identified.

The AIA exceptionally enables the processing of special categories of personal data provided that they offer adequate safeguards in relation to the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons. But it imposes additional conditions:

- the processing of other data, such as synthetic or anonymised data, does not allow effective detection and correction of biases;

- that special categories of personal data are subject to technical limitations concerning the re-use of personal data and to state-of-the-art security and privacy protection measures, including the pseudonymisation;

- that special categories of personal data are subject to measures to ensure that the personal data processed are secured, protected and subject to appropriate safeguards, including strict controls and documentation of access, to prevent misuse and to ensure that only authorised persons have access to such personal data with appropriate confidentiality obligations;

- that special categories of personal data are not transmitted or transferred to third parties and are not otherwise accessible to them;

- that special categories of personal data are deleted once the bias has been corrected or the personal data have reached the end of their retention period, whichever is the earlier;

- that the records of processing activities under Regulations (EU) 2016/679 and (EU) 2018/1725 and Directive (EU) 2016/680 include the reasons why the processing of special categories of personal data was strictly necessary for detecting and correcting bias, and why that purpose could not be achieved by processing other data.

The regulatory provisions are extremely interesting. RGPD, DGA or EHDS are in favour of processing anonymised data. AIA makes an exception in cases where inadequate or low-quality datasets are generated from a bias point of view.

Individual developers, data spaces and intermediary services providing datasets and/or platforms for development must be particularly diligent in defining their security. This provision is consistent with the requirement to have secure processing spaces in EHDS, implies a commitment to certifiable security standards, whether public or private, and advises a re-reading of the seventeenth additional provision on data processing in our Organic Law on Data Protection in the area of pseudonymisation, insofar as it adds ethical and legal guarantees to the strictly technical ones. Furthermore, the need to ensure adequate traceability of uses is underlined. In addition, it will be necessary to include in the register of processing activities a specific mention of this type of use and its justification.

Apply lessons learned from data protection, by design and by default

Article 10 of AIA requires the documentation of relevant design decisions and the identification of relevant data gaps or deficiencies that prevent compliance with AIA and how to address them. In short, it is not enough to ensure data governance, it is also necessary to provide documentary evidence and to maintain a proactive and vigilant attitude throughout the lifecycle of information systems.

These two obligations form the keystone of the system. And its reading should even be much broader in the legal dimension. Lessons learned from the GDPR teach that there is a dual condition for proactive accountability and the guarantee of fundamental rights. The first is intrinsic and material: the deployment of privacy engineering in the service of data protection by design and by default ensures compliance with the GDPR. The second is contextual: the processing of personal data does not take place in a vacuum, but in a broad and complex context regulated by other sectors of the law.

Data governance operates structurally from the foundation to the vault of AI-based information systems. Ensuring that it exists, is adequate and functional is essential. This is the understanding of the Spanish Government's Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2024 which seeks to provide the country with the levers to boost our development.

AIA makes a qualitative leap and underlines the functional approach from which data protection principles should be read by stressing the population dimension. This makes it necessary to rethink the conditions under which the GDPR has been complied with in the European Union. There is an urgent need to move away from template-based models that the consultancy company copies and pastes. It is clear that checklists and standardisation are indispensable. However, its effectiveness is highly dependent on fine tuning. And this calls particularly on the professionals who support the fulfilment of this objective to dedicate their best efforts to give deep meaning to the fulfilment of the Artificial Intelligence Regulation.

You can see a summary of the regulations in the following infographic:

Content prepared by Ricard Martínez, Director of the Chair of Privacy and Digital Transformation. Professor, Department of Constitutional Law, Universitat de València. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The European Union has devised a fundamental strategy to ensure accessible and reusable data for research, innovation and entrepreneurship. Strategic decisions have been made both in a regulatory and in a material sense to build spaces for data sharing and to foster the emergence of intermediaries with the capacity to process information.

European policies give rise to a very diverse ecosystem that should be differentiated. On the one hand, there is a deepening of open data reuse policies. On the other hand, the aim is to cover a space that has been inaccessible until now. We are referring to data that, due to the guarantee of the fundamental right to data protection, intellectual property or business secrecy, was inaccessible. Today, anonymization technologies, as well as data intermediation technologies, make it possible to process them with due guarantees. Finally, the aim is to provide resources through the promotion of data spaces, initiatives that propose federative models, such as Gaia X, or the European digital infrastructures (EDIC) promoted by the European Commission and the Digital Innovation Hubs aimed at promoting business and government in this field. This scenario will boost different types of use in research, invocation and entrepreneurship.

This article focuses on the agreement signed by the National Statistics Institute (INE), the State Tax Administration Agency (AEAT), different Social Security bodies, the State Public Employment Service (SEPE) and the Bank of Spain to boost access to data, which is part of this EU strategy whose principles, rules and conditions must be explained in order to place it in context, underline its importance and understand the implications of the agreement.

Competing by guaranteeing our rights

The EU competes at a structural disadvantage vis-à-vis the US or the People's Republic of China. On the North American side, the development processes of disruptive technologies in the context of the Internet and, particularly, the deployment of search engines, social networks and mobile applications have favoured the birth of a data broking market in which a few companies have an almost monopolistic power over data. The great champions of the digital world manage information on practically all sectors of activity, thanks to a business model based on the capitalisation or commoditisation of our privacy and their entry into sectors such as health or activity bracelets. Every time a user did a search, sent an email, commented on a social network or dictated a message to a mobile phone, it fuelled that position of dominance and underpinned the development of large language models in artificial intelligence or the deployment of algorithmic tools linked to neuroemotional marketing.

On the Chinese side, there is a closed internet model under state control, with a position of participation and surveillance over the large local multinationals in the sector and a global dominance over 5G network traffic. It is a vigilant state that has become the first power in the deployment of artificial intelligence through video surveillance and facial recognition and has a very clear state policy on the deployment of artificial intelligence (AI), creating advantages to compete in this race.

The EU starts from an apparently disadvantageous position. It is not at all a question of lack of talent or high abilities. Much of the Internet and IT ecosystem has been developed in Europe or by European talent. However, our market has not been able to generate conditions that would allow the emergence of major technological champions capable of supporting the entire value chain, from cloud infrastructures to the availability of large volumes of data that feed this ecosystem. Moreover, the EU adopted an ethical, political and legal commitment to freedoms, equity and democracy. This position, which has operated as a kind of barrier in terms of costs and processes, integrates within it the essential requirements for a democratic, inclusive and liberty-guaranteeing digital transformation.

The Data Governance Act

The legal substratum of data sharing is integrated by a complex modular structure integrating the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Open Data and Re-use of Public Sector Information Directive, the Data Governance Act (DGA), the Data Act (DA) and, in the immediate future, the artificial Intelligence Act and the European Health Data Space Regulation (EHDS). The rules should facilitate the re-use of data, including those under the scope of data protection, intellectual property and business secrecy. Several factors must operate to make this possible, which are set out below:

- Data sharing from government should grow exponentially and generate a data market that is currently monopolised by foreign companies.

- Digital sovereignty in legal terms will also be a growth driver insofar as it defines market rules based on the philosophy of the European Union centred on the guarantee of fundamental rights. This should have an immediate consequence when defining processes aimed at producing safe and reliable products.

- Digital sovereignty will in turn have important technological consequences. Public data spaces, whether promoted from digital hubs or federations of nodes, such as Gaia X, should make data available to the individual researcher or start-up, including application dashboards and technical support.

- The result of the regulation is to accelerate and increase the possibilities for freeing and sharing data. The EU and the convention under discussion seek to release data subject to trade secrecy, intellectual property or, in particular, the protection of personal data, in a secure manner through intermediation processes in secure data environments. This matter has occupied, among others, the Spanish Data Protection Agency and the European Cybersecurity Agency (ENISA). This implies a commitment to anonymisation and/or quasi-anonymisation environments through technologies such as differential privacy, homomorphic encryption and homomorphic encryption or multi-party computing.

All of this is based on the guarantee of fundamental rights and the empowerment of people. GDPR, DGA, DA and EHDS should make it possible to achieve the dual objective of creating a European market for the free movement and re-use of protected data. This ensures that individuals and organisations can exercise their rights of control and, at the same time, share these rights, while also encouraging data altruism. Moreover, the GDPR, DGA, EHDS and the artificial Intelligence Act define precise limits through prohibitions on use, regulated access conditions and ethically and legally sound design procedures. With an idea that should be considered central, there is a dimension of public or common interest that, beyond the epic battles of COVID, reaches the small but essential aspirations of the individual researcher, the disruptive entrepreneur, the SME trying to improve its value chain or the Administration innovating processes at the service of people.

Spain commits to the digital transformation of data spaces

The 2025 Plan, the Artificial Intelligence Strategy, the efforts of the Next Generation funds through its Strategic Projects for Economic Recovery and Transformation (PERTES in Spanish), the AI Missions and the Digital Bill of Rights exemplify Spain's alignment and leadership in this field. To make these strategies viable, secure data and process environments are essential. Now, the National Health Data Space has been joined by the agreement between the INE, the AEAT, different Social Security bodies, the SEPE and the Bank of Spain. As its explanatory memorandum states, it constitutes a first and encouraging step towards the deployment of DGA in our country.

They understand not only the scientific and business value of the statistical information they handle, but also the significant growth in demand and need for it. On the other hand, they take on a qualitatively relevant issue: the interest derived from the interconnection of datasets from the point of view of the value they bring. They therefore declare their willingness to maximise the added value of their data by allowing cross-referencing or integration when research is carried out for scientific purposes in the public interest.

The keys to the agreement to provide statistical data to researchers for scientific purposes in the public interest

Some of the questions that may arise with regard to this agreement are answered below.

-

How can the data be accessed?

Access to data goes through a cross-information access request that must be individually accepted by each institution. This takes into account certain assessment criteria regarding the nature of the data and the interest of the proposal.

Facilitating this access implies for the signatory institutions an effort of de-identification and cross-checking carried out by each of them directly or through trusted third parties. The result, "depending on the security level of the resulting file", will entail:

- A direct and autonomous access.

- A processing of the data in one of the secure rooms or centres made available by the signatory entities.

Some of the rooms currently available are:

Also noteworthy is the creation of ES_DataLab, which facilitates access to microdata in an environment that guarantees the confidentiality of the information. It allows cross-referencing data from different participating institutions, such as the INE, the AEAT, the Secretary of State for Social Security and Pensions, the Social Security General Treasury (TGSS), the National Social Security Institute (INSS), the Social Marine Institute (ISM), the Social Security IT Management (GISS), the State Public Employment Service and the Bank of Spain.

In implementation of the DGA 's plans, the Single National Information Point" (NSIP), managed by the General Directorate of Data, has been set up, from where citizens, business people or researchers can locate information on protected public sector data. This item is available at datos.gob.es.

-

What data is shared?

The volume and typologies of data they handle are truly significant. The press release presenting the agreement stated that it would be possible to access "the microdata bases owned by the INE, the AEAT, the SS and the BE, with the necessary guarantees of security, statistical secrecy, personal data protection and compliance with current legislation. In addition to statistical databases from its surveys, INE may also provide access to administrative registers, both those compiled or coordinated by INE and those under other ownership but which INE uses to compile its statistics (in the latter case consulting all requests for access to the holders of the corresponding registers)".

-

Who can access the data?

In order to grant access to the data, the confidentiality regime applicable to the data requested and its legal framework, the social interest of the results to be obtained in the research, the profile, trajectory and scientific publications of the principal investigator and associated researchers or the history of research projects of the entity backing the project, among other aspects, shall be taken into account.

One of the issues envisaged by the DGA in this area consists of establishing economic considerations that ensure the sustainability of the system. In any case, the third clause of the agreement provides for the possibility of receiving financial consideration from applicants for the services of preparing and making available the data contained in the databases owned by them, in accordance with the provisions of statistical legislation (Article 21.3 of the Law 12/1989 of 9 May 1989 on the Public Statistical Function - LFEP) and in the regulations governing each institution.

-

What challenges do data access requesters and signatories face?

Regardless of the scientific conditions of the research proposal, it is essential to appeal to the deploying institutions to significantly increase the quality of their data protection and information security compliance processes. But this will not be enough, the deployment of artificial intelligence requires the incorporation of additional processes that we can find in the document of the Conference of Rectors of Spanish Universities CRUE ICT 360º, addressed in 2023 for the assumption of the university. While it is true that the artificial Intelligence Act proposes a scenario of less regulation in basic research, it also requires a high level of ethical deployment. And to do so, it will be essential to apply principles of artificial intelligence ethics, with the model ALTAI (Assessment List for Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence) or an alternative model, and to the Fundamental Rights Impact Analysis (FRAIA). This is without neglecting the high legal requirements for the development of market-oriented systems. Beyond the formal declarations of the Convention, the lessons learned from European projects affirm the need for a procedural framework of evidence-based legal and ethical verification of research projects and the capacities of institutions requesting access to data.

From the point of view of the signatory institutions, in addition to the challenge of the economic sustainability of the model, foreseen and regulated in the agreement, the need for a regulatory investment strategy seems evident. We have no doubt that each data repository and the processes underpinning them have been subject to a data protection impact assessment and security methodologies linked to the National Scheme. Data protection by design and by default or compliance with the recommendations on anonymisation and data space management mentioned above will be further elements considered. This translates into processes, but also into people - chief data officers, data analysts, other mediators such as data protection officers, etc. - together with a high level of security requirements. On the other hand, the duty of transparency vis-à-vis citizens will require efficient channels and a very precise risk management model in the event of a possible mass exercise of a right to object to processing, without prejudice to its feasibility.

Finally, the Spanish Data Protection Agency should approach this process in a proactive and promotional way without renouncing its role as guarantor of fundamental rights, but contributing to the development of functional solutions. This is not just any agreement but an essential test bed for the future of data research in Spain.

In our opinion, the most exciting statement of these institutions consists of understanding the agreement "as the embryo of the future System of access to data for research for scientific purposes of public interest, which must be in accordance with the Spanish and European strategy on data and the legislation on its governance, within a framework of development of public sector data spaces, and respecting in any case the autonomy and the legal regime applicable to the Banco de España".

Content prepared by Ricard Martínez, Director of the Chair of Privacy and Digital Transformation. Professor, Department of Constitutional Law, Universitat de València. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

Building the European Health Data Space is one of the challenges of our generation. The COVID 19 pandemic put us in front of the mirror and brought back at least two images. The first was none other than the result of the application of formalistic, bureaucratised and old-fashioned models of data management. Second, the enormous potential offered by data sharing, collaboration of interdisciplinary teams and the use of health information for the common good. The European Union is clearly committed to the second strategy. This article examines the challenges of building a National Health Data Space as an instrument to enhance the reuse of health data for secondary uses from a variety of perspectives.

The error of focusing on formalist visions

The data processing and sharing scenario prior to the deployment of the European data strategy and its commitment to data spaces produced not only counter-intuitive, but also counter-factual effects. The framework of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) instead of favouring processing operated as a barrier. Strict enforcement was chosen, based on the prevalence of privacy. Instead of seeking to manage risk through legal and technical solutions, the decision was made not to process data or to use technically complex anonymisations that are unfeasible in practice.

This model is not sustainable. Technological acceleration forces a shift in the centre of gravity from prohibition to risk management and data governance. And this is what Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the European Health Data Space (EHDS) is committed to: finding solutions and defining guarantees to protect people. And this transformation finds Spain's healthcare sector in an unbeatable situation from any point of view, although it is not without risks.

Spain, a pioneer in the change of approach

Our country did its homework with the seventeenth additional provision on the processing of health data in Organic Law 3/2018, of 5 December, on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights (LOPDGDD, in Spanish acronyms). The regulation circumvented most of the problems affecting the secondary use of health data and did so with the methodology derived from the GDPR and the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court. To this end, he opted for:

- A clear systematisation and normative predetermination of use cases.

- A precise definition of treatment entitlements.

- Procedural, contractual and security guarantees.

The Provision was five years ahead of the EHDS in terms of its aims, objectives and safeguards. Not only that, it puts our healthcare system at a competitive advantage from a legal and material point of view.

From this point of view, the National Health Data Space as the backbone is a project that is as essential as it is unpostponable, as reflected in the National Health System's Digital Health strategy and the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan. However, this assertion cannot be based on uncritical enthusiasm. Much work remains to be done.

Lessons learned and challenges to overcome

European research projects managed by the ecosystem of health foundations at the Carlos Tercero Institute, university and business, provide interesting lessons. In our country we are working on precision medicine, on the construction of data lakes, on mobile applications, on high capacities of pseudonymisation and anonymisation, on medical imaging, on predictive artificial intelligence..., and we could go on. This ecosystem needs a layer of governance innovation. Part of it will be provided directly by the EHDS. Data access bodies, the supervisory authority and cross-border access structures shall ensure the lifecycle from the formation of catalogued and reliable datasets to their actual processing. These governance infrastructures require an organisational and human deployment to support them. Previous experience helps to anticipate the risks that a stress test may pose for the whole value chain:

- The training of human resources in crucial aspects of data protection, information security and new ethical requirements is not always adequate in terms of format, volume and profile segmentation. Not 100% of the workforce is trained, while voluntary continuing education for health professionals is of a high legal standard, causing an effect that is as counterproductive as it is perverse: curtailing the capacity to innovate. If instead of empowering and engaging, we offer an endless list of GDPR obligations, research staff end up self-censoring their ability to imagine. The content and the training target are confused. High-level training should focus on project managers and technical and legal support staff. And in these, data protection officer plays a vehicular role, as it is the person who must provide non-binary advice - of the legal or non-legal type - and cannot transfer all the responsibility to the research team.

- Governance of treatment resources and processes needs to be improved. In certain research areas, and universities are the best example of this, information systems are segmented and managed at the smallest project or research team level. These are insufficient resources, with little control over risk management and security monitoring, including support for the management and maintenance of the treatment environment. Moreover, data access procedures are based on rigid models, anchored in the case study or clinical trial. Thus, more often than not, we handle datasets in very specific environments outside the main data processing centres. This multiplies the risk, and the costs, in areas such as data protection impact assessments or the deployment of security measures.

Lack of expertise can pose systemic risks. To begin with, Ethics Committees are confronted with issues of data protection and artificial intelligence ethics that overwhelm their habits, customs and knowledge, and mothball their processes. On the other hand, what we commonly refer to as big data is not something that happens by magic. Pseudonymisation or anonymisation, annotation, enrichment and validation of the dataset and the processes implemented on it require highly skilled professionals.

Effects of EHDS

We should reflect on whether our leading position in digitisation could also be our Achilles' heel. Few countries have a high degree of digitisation of every level of healthcare, from primary to hospital. Virtually none have regulated the use of pseudonymised data without consent, nor the broad consent model of our LOPDGDD. In this sense, under the umbrella of the EHDS there could be two effects that we need to manage:

- New opportunities in research projects. Firstly, as soon as Spanish health institutions publish their data catalogues at European level, requests for access from other countries could multiply. And, therefore, the opportunities to participate in research projects as information providers, data holders, or as data users.

- Boosting the ecosystem of innovative companies. Moreover, the wide range of secondary uses foreseen by the EHDS will broaden the profile of actors submitting data access requests. This points to the possibility of a unique ecosystem of innovative companies for the deployment of health solutions from wellness to artificial intelligence-assisted medical diagnostics.

This forces those responsible for the public health system to ask themselves a rather simple question: what level of availability, process capability, security and interoperability can the available information systems offer? Let us not forget that many trans-European research projects, or the deployment of Artificial Intelligence tools in the health sector, are backed by budgets running into millions. This presents enormous opportunities to deepen the deployment of new models of health service delivery that also feed back into research, innovation and entrepreneurship. But there is also the risk of not being able to take advantage of the available resources due to shortcomings in the design of repositories and their processing capabilities.

What data space model are we pursuing?

The answer to this question can be found very clearly both in the European Union's data space strategy and in the Spanish Government's own strategy. The task that the EHDS attributes to data access bodies, beyond the mere granting of an access permit, is to support and assist in the development of the processing. This requires a National Health Data Space to ensure service level, anonymisation or pseudonymisation standards, interoperability and information security.

In this context, individual researchers in non-health settings, but especially small and medium-sized innovative companies, do not possess the necessary muscle and expertise to meet ethical and regulatory requirements. Therefore, the need to provide them with support in terms of the design of regulatory and ethical compliance models should not be neglected, if they are not to act as a barrier to entry or exclusion.

This does not exclude or preclude regional efforts, those of foundations or reference hospitals, or nascent data infrastructures in the field of medical imaging of cancer or genomics. It is precisely the idea of a federation of data spaces that inspires European legislation that can bear fruit of the highest quality here. The Ministry of Health and public health departments should move in this direction, with the support of the new Ministry of Digital Transformation and Public Administration. The autonomous communities reflect and act on the development of governable models and participate, together with the Ministry of Health, in the governance model that should govern the national framework. Regulators such as the Spanish Data Protection Agency are providing viable frameworks for the development of data spaces. Entire hospitals design, implement and deploy information systems that seek to integrate hundreds of data sources and generate data lakes for research. Data infrastructures such as EUCAIM lead the way and generate high-quality know-how in highly specialised areas.

The work on the roll-out of a National Health Data Space, and each and every one of the unique initiatives underway, show us a way forward in which the federation of effort, solidarity and data sharing ensure that our privileged position in health digitisation stimulates leadership in research, innovation and digital entrepreneurship. The National Health Data Space will be able to offer differential value to stakeholders. It will provide data quality and volume, support advanced compute-intensive data analytics and AI tools and can provide security in software brokering processes for the processing of pseudonymised data with high requirements.

It is necessary to recall a core value for the European Union: the guarantee of fundamental rights and the human-centred approach. The Charter of Digital Rights promoted by the Spanish government proposes successively the right of access to data for scientific research, innovation and development purposes, as well as the right to the protection of health in the digital environment. The National Health Data Space is called to be the indispensable instrument to achieve a sustainable, inclusive digital health at the service of the common good, which at the same time boosts this dimension of the data economy, promoting research and entrepreneurship in our country.

Content prepared by Ricard Martínez, Director of the Chair of Privacy and Digital Transformation. Professor, Department of Constitutional Law, Universitat de València. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The Council of Ministers approved in February this year the Sustainable Mobility Bill (PL), a commitment to a digital and innovative transport system in which open mobility data will play a key role.

Inaddition to regulating innovative solutions such as on-demand transport, car sharing or temporary use of vehicles, the regulation will encourage the promotion ofopen data by administrations, infrastructure managers and public and private operators. All this, as stated in Chapter III Title V of the Draft Law "will bring enormous benefits to citizens, e.g. for new mobility and their contribution to the European Green Pact".

This Bill is aligned with the European Data Strategy, which has among its objectives to create a single market for data that ensures Europe' s global competitiveness and data sovereignty through the creation of common European data spaces common European data spaces in nine strategic sectors. In particular, it foresees the creation and development of a common European mobility data space to put Europe at the forefront of the development of a smart transport system, including connected cars and other modes of transport. Along these lines, the European Commission presented its Sustainable and Intelligent Mobility Strategywhich includes an action dedicated to innovation, data and artificial intelligence for smarter mobility. Following in Europe's footsteps, Spain has launched this Sustainable Mobility Bill.

In this post we look at the benefits that the use of open data can bring to the sector, the obligations that the PL will place on data, and the next steps in building the Integrated Mobility Data Space.

Benefits of using open data on sustainable mobility

The Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility, in the web section created for the Law, identifies some of the benefits that access to and use of open transport and mobility data can offer both to the business community and to public administrations and citizens in general:

- Encourage the development of applications that enable citizens to make decisions on the planning of their journeys and during the course of their journeys.

- Improve the conditions of service provision and the travel experience .

- Incentivise research, create new developments and businesses from the data generated in the transport and mobility ecosystem.

- Enable public administrations to have a better understanding of the transport and mobility system in order to improve the definition of public policies and the management of the system.

- Encourage the use of this data for other public interest purposes that may arise.

Ensuring access to open mobility data

In order to make good use of these data and thus take advantage of all the benefits they offer, the Draft Law determines a strategy to ensure the availability of open data in the field of transport and mobility. This strategy concerns:

- transport companies and infrastructure managers, which must drive digitalisation and provide a significant part of the data, with specific characteristics and functionalities.

- administrations and public entities were already obliged to ensure the openness of their data by design, as well as its re-use on the basis of the already existing

In short, the guidelines for re-use already defined in Law 37/2007 for the public sector are respected, and the need to regulate access to this information and the way in which this data is used by third parties, i.e. companies in the sector, is also included.

Integrated Mobility Data Space

In line with the European Data Strategy mentioned at the beginning of the post, the PL determines the obligation to create the Integrated Mobility Data Space (EDIM) under the direction of the Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility, in coordination with the Secretary of State for Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence. In the EDIM, the aforementioned transport companies, infrastructure managers and administrations will share their data, which will optimise the decision making of all actors when planning the implementation of new infrastructures and the launch of new services.

The Draft Law defines some characteristics of the Integrated Mobility Data Space such as the modular structure, which will include information in a systematic way on different areas of urban, metropolitan and interurban mobility, both for people and goods.

Specifically, the EDIM, according to Article 14, would collect data "in digital form in a free, non-discriminatory and up-to-date manner" on:

- Supply and demand of the different modes of transport and mobility, information on public transport services and mobility services under the responsibility of the administrations

- Financial situation and costs of providing services for all modes of public transport, investments in transport infrastructure, inventory of transport infrastructure and terminals, conditions and degree of accessibility.

- Other data to be agreed at the Sectoral Conference on Transport.

It identifies examples of this type of data and information on the responsibility for its provision, format, frequency of updating and other characteristics.

As referred to in the CP, the data and information managed by the EDIM will provide an integrated vision to analyse and facilitate mobility management, improving the design of sustainable and efficient solutions, and transparency in the design of public transport and mobility policies. In addition, the Law will promote the creation of a sandbox or test environment to serve as an incubator for innovative mobility projects. The outcome of the tests will allow both the developer and the administration to learn by observing the market in a controlled environment.

National Bimodal Transport Access Point

On the other hand, the Bill also provides for the creation of a National Bimodal Transport Access Point that will collect the information communicated to the Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility in the framework of the priority action "Provision of information services on multimodal journeys throughout the Union" of Directive 2010/40/EU which refers to the transport of goods and/or persons by more than one means of transport.

This information will be freely accessible and will also serve to feed the EDIM in the area related to the characterisation of transport and mobility of persons, as well as the National Catalogue of Public Information maintained by the General State Administration.

The Bill defines that the provision of services to citizens using transport and mobility data from the National Multimodal Transport Access Point must be done in a fair, neutral, impartial, non-discriminatory and transparent manner. It adds that the Ministry of Transport and Sustainable Mobility will propose rules for the use of such data within 12 months after the entry into force of this law.

The Sustainable Mobility Bill is currently in parliamentary procedure, as it has been sent to the Spanish Parliament for urgent processing and approval in 2024.