In the usual search for tricks to make our prompts more effective, one of the most popular is the activation of the chain of thought. It consists of posing a multilevel problem and asking the AI system to solve it, but not by giving us the solution all at once, but by making visible step by step the logical line necessary to solve it. This feature is available in both paid and free AI systems, it's all about knowing how to activate it.

Originally, the reasoning string was one of many tests of semantic logic that developers put language models through. However, in 2022, Google Brain researchers demonstrated for the first time that providing examples of chained reasoning in the prompt could unlock greater problem-solving capabilities in models.

From this moment on, little by little, it has positioned itself as a useful technique to obtain better results from use, being very questioned at the same time from a technical point of view. Because what is really striking about this process is that language models do not think in a chain: they are only simulating human reasoning before us.

How to activate the reasoning chain

There are two possible ways to activate this process in the models: from a button provided by the tool itself, as in the case of DeepSeek with the "DeepThink" button that activates the R1 model:

Figure 1. DeepSeek with the "DeepThink" button that activates the R1 model.

Or, and this is the simplest and most common option, from the prompt itself. If we opt for this option, we can do it in two ways: only with the instruction (zero-shot prompting) or by providing solved examples (few-shot prompting).

- Zero-shot prompting: as simple as adding at the end of the prompt an instruction such as "Reason step by step", or "Think before answering". This assures us that the chain of reasoning will be activated and we will see the logical process of the problem visible.

Figure 2. Example of Zero-shot prompting.

- Few-shot prompting: if we want a very precise response pattern, it may be interesting to provide some solved question-answer examples. The model sees this demonstration and imitates it as a pattern in a new question.

Figure 3. Example of Few-shot prompting.

Benefits and three practical examples

When we activate the chain of reasoning, we are asking the system to "show" its work in a visible way before our eyes, as if it were solving the problem on a blackboard. Although not completely eliminated, forcing the language model to express the logical steps reduces the possibility of errors, because the model focuses its attention on one step at a time. In addition, in the event of an error, it is much easier for the user of the system to detect it with the naked eye.

When is the chain of reasoning useful? Especially in mathematical calculations, logical problems, puzzles, ethical dilemmas or questions with different stages and jumps (called multi-hop). In the latter, it is practical, especially in those in which you have to handle information from the world that is not directly included in the question.

Let's see some examples in which we apply this technique to a chronological problem, a spatial problem and a probabilistic problem.

-

Chronological reasoning

Let's think about the following prompt:

If Juan was born in October and is 15 years old, how old was he in June of last year?

Figure 5. Example of chronological reasoning.

For this example we have used the GPT-o3 model, available in the Plus version of ChatGPT and specialized in reasoning, so the chain of thought is activated as standard and it is not necessary to do it from the prompt. This model is programmed to give us the information of the time it has taken to solve the problem, in this case 6 seconds. Both the answer and the explanation are correct, and to arrive at them the model has had to incorporate external information such as the order of the months of the year, the knowledge of the current date to propose the temporal anchorage, or the idea that age changes in the month of the birthday, and not at the beginning of the year.

-

Spatial reasoning

-

A person is facing north. Turn 90 degrees to the right, then 180 degrees to the left. In what direction are you looking now?

Figure 6. Example of spatial reasoning.

This time we have used the free version of ChatGPT, which uses the GPT-4o model by default (although with limitations), so it is safer to activate the reasoning chain with an indication at the end of the prompt: Reason step by step. To solve this problem, the model needs general knowledge of the world that it has learned in training, such as the spatial orientation of the cardinal points, the degrees of rotation, laterality and the basic logic of movement.

-

Probabilistic reasoning

-

In a bag there are 3 red balls, 2 green balls and 1 blue ball. If you draw a ball at random without looking, what's the probability that it's neither red nor blue?

Figure 7. Example of probabilistic reasoning.

To launch this prompt we have used Gemini 2.5 Flash, in the Gemini Pro version of Google. The training of this model was certainly included in the fundamentals of both basic arithmetic and probability, but the most effective for the model to learn to solve this type of exercise are the millions of solved examples it has seen. Probability problems and their step-by-step solutions are the model to imitate when reconstructing this reasoning.

The Great Simulation

And now, let's go with the questioning. In recent months, the debate about whether or not we can trust these mock explanations has grown, especially since, ideally, the chain of thought should faithfully reflect the internal process by which the model arrives at its answer. And there is no practical guarantee that this will be the case.

The Anthropic team (creators of Claude, another great language model) has carried out a trap experiment with Claude Sonnet in 2025, to which they suggested a key clue for the solution before activating the reasoned response.

Think of it like passing a student a note that says "the answer is [A]" before an exam. If you write on your exam that you chose [A] at least in part because of the grade, that's good news: you're being honest and faithful. But if you write down what claims to be your reasoning process without mentioning the note, we might have a problem.

The percentage of times Claude Sonnet included the track among his deductions was only 25%. This shows that sometimes models generate explanations that sound convincing, but that do not correspond to their true internal logic to arrive at the solution, but are rationalizations a posteriori: first they find the solution, then they invent the process in a coherent way for the user. This shows the risk that the model may be hiding steps or relevant information for the resolution of the problem.

Closing

Despite the limitations exposed, as we see in the study mentioned above, we cannot forget that in the original Google Brain research, it was documented that, when applying the reasoning chain, the PaLM model improved its performance in mathematical problems from 17.9% to 58.1% accuracy. If, in addition, we combine this technique with the search in open data to obtain information external to the model, the reasoning improves in terms of being more verifiable, updated and robust.

However, by making language models "think out loud", what we are really improving in 100% of cases is the user experience in complex tasks. If we do not fall into the excessive delegation of thought to AI, our own cognitive process can benefit. It is also a technique that greatly facilitates our new work as supervisors of automatic processes.

Content prepared by Carmen Torrijos, expert in AI applied to language and communication. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Sport has always been characterized by generating a lot of data, statistics, graphs... But accumulating figures is not enough. It is necessary to analyze the data, draw conclusions and make decisions based on it. The advantages of sharing data in this sector go beyond mere sports, having a positive impact on health and the economic sphere. they go beyond mere sports, having a positive impact on health and the economic sphere.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has also reached the professional sports sector and its ability to process huge amounts of data has opened the door to making the most of the potential of all that information. Manchester City, one of the best-known football clubs in the British Premier League, was one of the pioneers in using artificial intelligence to improve its sporting performance: it uses AI algorithms for the selection of new talent and has collaborated in the development of WaitTime, an artificial intelligence platform that manages the attendance of crowds in large sports and leisure venues. In Spain, Real Madrid, for example, incorporated the use of artificial intelligence a few years ago and promotes forums on the impact of AI on sport.

Artificial intelligence systems analyze extensive volumes of data collected during training and competitions, and are able to provide detailed evaluations on the effectiveness of strategies and optimization opportunities. In addition, it is possible to develop alerts on injury risks, allowing prevention measures to be established, or to create personalized training plans that are automatically adapted to each athlete according to their individual needs. These tools have completely changed contemporary high-level sports preparation. In this post we are going to review some of these use cases.

From simple observation to complete data management to optimize results

Traditional methods of sports evaluation have evolved into highly specialized technological systems. Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools process massive volumes of information during training and competitions, converting statistics, biometric data and audiovisual content into strategic insights for the management of athletes' preparation and health.

Real-time performance analysis systems are one of the most established implementations in the sports sector. To collect this data, it is common to see athletes training with bands or vests that monitor different parameters in real time. Both these and other devices and sensors record movements, speeds and biometric data. Heart rate, speed or acceleration are some of the most common data. AI algorithms process this information, generating immediate results that help optimize personalized training programs for each athlete and tactical adaptations, identifying patterns to locate areas for improvement.

In this sense, sports artificial intelligence platforms evaluate both individual performance and collective dynamics in the case of team sports. To evaluate the tactical area, different types of data are analyzed according to the sports modality. In endurance disciplines, speed, distance, rhythm or power are examined, while in team sports data on the position of the players or the accuracy of passes or shots are especially relevant.

Another advance is AI cameras, which allow you to follow the trajectory of players on the field and the movements of different elements, such as the ball in ball sports. These systems generate a multitude of data on positions, movements and patterns of play. The analysis of these historical data sets allows us to identify strategic strengths and vulnerabilities both our own and those of our opponents. This helps to generate different tactical options and improve decision-making before a competition.

Health and well-being of athletes

Sports injury prevention systems analyze historical data and metrics in real-time. Its algorithms identify injury risk patterns, allowing personalized preventive measures to be taken for each athlete. In the case of football, teams such as Manchester United, Liverpool, Valencia CF and Getafe CF have been implementing these technologies for several years.

In addition to the data we have seen above, sports monitoring platforms also record physiological variables continuously: heart rate, sleep patterns, muscle fatigue and movement biomechanics. Wearable devices with artificial intelligence capabilities detect indicators of fatigue, imbalances, or physical stress that precede injuries. With this data, the algorithms predict patterns that detect risks and make it easier to act preventively, adjusting training or developing specific recovery programs before an injury occurs. In this way, training loads, rep volume, intensity and recovery periods can be calibrated according to individual profiles. This predictive maintenance for athletes is especially relevant for teams and clubs in which athletes are not only sporting assets, but also economic ones. In addition, these systems also optimise sports rehabilitation processes, reducing recovery times in muscle injuries by up to 30% and providing predictions on the risk of relapse.

While not foolproof, the data indicates that these platforms predict approximately 50% of injuries during sports seasons, although they cannot predict when they will occur. The application of AI to healthcare in sport thus contributes to the extension of professional sports careers, facilitating optimal performance and the athlete's athletic well-being in the long term.

Improving the audience experience

Artificial intelligence is also revolutionizing the way fans enjoy sport, both in stadiums and at home. Thanks to natural language processing (NLP) systems, viewers can follow comments and subtitles in real time, facilitating access for people with hearing impairments or speakers of other languages. Manchester City has recently incorporated this technology for the generation of real-time subtitles on the screens of its stadium. These applications have also reached other sports disciplines: IBM Watson has developed a functionality that allows Wimbledon fans to watch the videos with highlighted commentary and AI-generated subtitles.

In addition, AI optimises the management of large capacities through sensors and predictive algorithms, speeding up access, improving security and customising services such as seat locations. Even in broadcasts, AI-powered tools offer instant statistics, automated highlights, and smart cameras that follow the action without human intervention, making the experience more immersive and dynamic. The NBA uses Second Spectrum, a system that combines cameras with AI to analyze player movements and create visualizations, such as passing routes or shot probabilities. Other sports, such as golf or Formula 1, also use similar tools that enhance the fan experience.

Data privacy and other challenges

The application of AI in sport also poses significant ethical challenges. The collection and analysis of biometric information raises doubts about the security and protection of athletes' personal data, so it is necessary to establish protocols that guarantee the management of consent, as well as the ownership of such data.

Equity is another concern, as the application of artificial intelligence gives competitive advantages to teams and organizations with greater economic resources, which can contribute to perpetuating inequalities.

Despite these challenges, artificial intelligence has radically transformed the professional sports landscape. The future of sport seems to be linked to the evolution of this technology. Its application promises to continue to elevate athlete performance and the public experience, although some challenges need to be overcome.

Artificial intelligence is no longer a thing of the future: it is here and can become an ally in our daily lives. From making tasks easier for us at work, such as writing emails or summarizing documents, to helping us organize a trip, learn a new language, or plan our weekly menus, AI adapts to our routines to make our lives easier. You don't have to be tech-savvy to take advantage of it; while today's tools are very accessible, understanding their capabilities and knowing how to ask the right questions will maximize their usefulness.

AI Passive and Active Subjects

The applications of artificial intelligence in everyday life are transforming our daily lives. AI already covers multiple fields of our routines. Virtual assistants, such as Siri or Alexa, are among the most well-known tools that incorporate artificial intelligence, and are used to answer questions, schedule appointments, or control devices.

Many people use tools or applications with artificial intelligence on a daily basis, even if it operates imperceptibly to the user and does not require their intervention. Google Maps, for example, uses AI to optimize routes in real time, predict traffic conditions, suggest alternative routes or estimate the time of arrival. Spotify applies it to personalize playlists or suggest songs, and Netflix to make recommendations and tailor the content shown to each user.

But it is also possible to be an active user of artificial intelligence using tools that interact directly with the models. Thus, we can ask questions, generate texts, summarize documents or plan tasks. AI is no longer a hidden mechanism but a kind of digital co-pilot that assists us in our day-to-day lives. ChatGPT, Copilot or Gemini are tools that allow us to use AI without having to be experts. This makes it easier for us to automate daily tasks, freeing up time to spend on other activities.

AI in Home and Personal Life

Virtual assistants respond to voice commands and inform us what time it is, the weather or play the music we want to listen to. But their possibilities go much further, as they are able to learn from our habits to anticipate our needs. They can control different devices that we have in the home in a centralized way, such as heating, air conditioning, lights or security devices. It is also possible to configure custom actions that are triggered via a voice command. For example, a "good morning" routine that turns on the lights, informs us of the weather forecast and the traffic conditions.

When we have lost the manual of one of the appliances or electronic devices we have at home, artificial intelligence is a good ally. By sending a photo of the device, you will help us interpret the instructions, set it up, or troubleshoot basic issues.

If you want to go further, AI can do some everyday tasks for you. Through these tools we can plan our weekly menus, indicating needs or preferences, such as dishes suitable for celiacs or vegetarians, prepare the shopping list and obtain the recipes. It can also help us choose between the dishes on a restaurant's menu taking into account our preferences and dietary restrictions, such as allergies or intolerances. Through a simple photo of the menu, the AI will offer us personalized suggestions.

Physical exercise is another area of our personal lives in which these digital co-pilots are very valuable. We may ask you, for example, to create exercise routines adapted to different physical conditions, goals and available equipment.

Planning a vacation is another of the most interesting features of these digital assistants. If we provide them with a destination, a number of days, interests, and even a budget, we will have a complete plan for our next trip.

Applications of AI in studies

AI is profoundly transforming the way we study, offering tools that personalize learning. Helping the little ones in the house with their schoolwork, learning a language or acquiring new skills for our professional development are just some of the possibilities.

There are platforms that generate personalized content in just a few minutes and didactic material made from open data that can be used both in the classroom and at home to review. Among university students or high school students, some of the most popular options are applications that summarize or make outlines from longer texts. It is even possible to generate a podcast from a file, which can help us understand and become familiar with a topic while playing sports or cooking.

But we can also create our applications to study or even simulate exams. Without having programming knowledge, it is possible to generate an application to learn multiplication tables, irregular verbs in English or whatever we can think of.

How to Use AI in Work and Personal Finance

In the professional field, artificial intelligence offers tools that increase productivity. In fact, it is estimated that in Spain 78% of workers already use AI tools in the workplace. By automating processes, we save time to focus on higher-value tasks. These digital assistants summarize long documents, generate specialized reports in a field, compose emails, or take notes in meetings.

Some platforms already incorporate the transcription of meetings in real time, something that can be very useful if we do not master the language. Microsoft Teams, for example, offers useful options through Copilot from the "Summary" tab of the meeting itself, such as transcription, a summary or the possibility of adding notes.

The management of personal finances has also evolved thanks to applications that use AI, allowing you to control expenses and manage a budget. But we can also create our own personal financial advisor using an AI tool, such as ChatGPT. By providing you with insights into income, fixed expenses, variables, and savings goals, it analyzes the data and creates personalized financial plans.

Prompts and creation of useful applications for everyday life

We have seen the great possibilities that artificial intelligence offers us as a co-pilot in our day-to-day lives. But to make it a good digital assistant, we must know how to ask it and give it precise instructions.

A prompt is a basic instruction or request that is made to an AI model to guide it, with the aim of providing us with a coherent and quality response. Good prompting is the key to getting the most out of AI. It is essential to ask well and provide the necessary information.

To write effective prompts we have to be clear, specific, and avoid ambiguities. We must indicate what the objective is, that is, what we want the AI to do: summarize, translate, generate an image, etc. It is also key to provide it with context, explaining who it is aimed at or why we need it, as well as how we expect the response to be. This can include the tone of the message, the formatting, the fonts used to generate it, etc.

Here are some tips for creating effective prompts:

- Use short, direct and concrete sentences. The clearer the request, the more accurate the answer. Avoid expressions such as "please" or "thank you", as they only add unnecessary noise and consume more resources. Instead, use words like "must," "do," "include," or "list." To reinforce the request, you can capitalize those words. These expressions are especially useful for fine-tuning a first response from the model that doesn't meet your expectations.

- It indicates the audience to which it is addressed. Specify whether the answer is aimed at an expert audience, inexperienced audience, children, adolescents, adults, etc. When we want a simple answer, we can, for example, ask the AI to explain it to us as if we were ten years old.

- Use delimiters. Separate the instructions using a symbol, such as slashes (//) or quotation marks to help the model understand the instruction better. For example, if you want it to do a translation, it uses delimiters to separate the command ("Translate into English") from the phrase it is supposed to translate.

- Indicates the function that the model should adopt. Specifies the role that the model should assume to generate the response. Telling them whether they should act like an expert in finance or nutrition, for example, will help generate more specialized answers as they will adapt both the content and the tone.

- Break down entire requests into simple requests. If you're going to make a complex request that requires an excessively long prompt, it's a good idea to break it down into simpler steps. If you need detailed explanations, use expressions like "Think by step" to give you a more structured answer.

- Use examples. Include examples of what you're looking for in the prompt to guide the model to the answer.

- Provide positive instructions. Instead of asking them not to do or include something, state the request in the affirmative. For example, instead of "Don't use long sentences," say, "Use short, concise sentences." Positive instructions avoid ambiguities and make it easier for the AI to understand what it needs to do. This happens because negative prompts put extra effort on the model, as it has to deduce what the opposite action is.

- Offer tips or penalties. This serves to reinforce desired behaviors and restrict inappropriate responses. For example, "If you use vague or ambiguous phrases, you will lose 100 euros."

- Ask them to ask you what they need. If we instruct you to ask us for additional information we reduce the possibility of hallucinations, as we are improving the context of our request.

- Request that they respond like a human. If the texts seem too artificial or mechanical, specify in the prompt that the response is more natural or that it seems to be crafted by a human.

- Provides the start of the answer. This simple trick is very useful in guiding the model towards the response we expect.

- Define the fonts to use. If we narrow down the type of information you should use to generate the answer, we will get more refined answers. It asks, for example, that it only use data after a specific year.

- Request that it mimic a style. We can provide you with an example to make your response consistent with the style of the reference or ask you to follow the style of a famous author.

While it is possible to generate functional code for simple tasks and applications without programming knowledge, it is important to note that developing more complex or robust solutions at a professional level still requires programming and software development expertise. To create, for example, an application that helps us manage our pending tasks, we ask AI tools to generate the code, explaining in detail what we want it to do, how we expect it to behave, and what it should look like. From these instructions, the tool will generate the code and guide us to test, modify and implement it. We can ask you how and where to run it for free and ask for help making improvements.

As we've seen, the potential of these digital assistants is enormous, but their true power lies in large part in how we communicate with them. Clear and well-structured prompts are the key to getting accurate answers without needing to be tech-savvy. AI not only helps us automate routine tasks, but it expands our capabilities, allowing us to do more in less time. These tools are redefining our day-to-day lives, making it more efficient and leaving us time for other things. And best of all: it is now within our reach.

Generative artificial intelligence is beginning to find its way into everyday applications ranging from virtual agents (or teams of virtual agents) that resolve queries when we call a customer service centre to intelligent assistants that automatically draft meeting summaries or report proposals in office environments.

These applications, often governed by foundational language models (LLMs), promise to revolutionise entire industries on the basis of huge productivity gains. However, their adoption brings new challenges because, unlike traditional software, a generative AI model does not follow fixed rules written by humans, but its responses are based on statistical patterns learned from processing large volumes of data. This makes its behaviour less predictable and more difficult to explain, and sometimes leads to unexpected results, errors that are difficult to foresee, or responses that do not always align with the original intentions of the system's creator.

Therefore, the validation of these applications from multiple perspectives such as ethics, security or consistency is essential to ensure confidence in the results of the systems we are creating in this new stage of digital transformation.

What needs to be validated in generative AI-based systems?

Validating generative AI-based systems means rigorously checking that they meet certain quality and accountability criteria before relying on them to solve sensitive tasks.

It is not only about verifying that they ‘work’, but also about making sure that they behave as expected, avoiding biases, protecting users, maintaining their stability over time, and complying with applicable ethical and legal standards. The need for comprehensive validation is a growing consensus among experts, researchers, regulators and industry: deploying AI reliably requires explicit standards, assessments and controls.

We summarize four key dimensions that need to be checked in generative AI-based systems to align their results with human expectations:

- Ethics and fairness: a model must respect basic ethical principles and avoid harming individuals or groups. This involves detecting and mitigating biases in their responses so as not to perpetuate stereotypes or discrimination. It also requires filtering toxic or offensive content that could harm users. Equity is assessed by ensuring that the system offers consistent treatment to different demographics, without unduly favouring or excluding anyone.

- Security and robustness: here we refer to both user safety (that the system does not generate dangerous recommendations or facilitate illicit activities) and technical robustness against errors and manipulations. A safe model must avoid instructions that lead, for example, to illegal behavior, reliably rejecting those requests. In addition, robustness means that the system can withstand adversarial attacks (such as requests designed to deceive you) and that it operates stably under different conditions.

- Consistency and reliability: Generative AI results must be consistent, consistent, and correct. In applications such as medical diagnosis or legal assistance, it is not enough for the answer to sound convincing; it must be true and accurate. For this reason, aspects such as the logical coherence of the answers, their relevance with respect to the question asked and the factual accuracy of the information are validated. Its stability over time is also checked (that in the face of two similar requests equivalent results are offered under the same conditions) and its resilience (that small changes in the input do not cause substantially different outputs).

- Transparency and explainability: To trust the decisions of an AI-based system, it is desirable to understand how and why it produces them. Transparency includes providing information about training data, known limitations, and model performance across different tests. Many companies are adopting the practice of publishing "model cards," which summarize how a system was designed and evaluated, including bias metrics, common errors, and recommended use cases. Explainability goes a step further and seeks to ensure that the model offers, when possible, understandable explanations of its results (for example, highlighting which data influenced a certain recommendation). Greater transparency and explainability increase accountability, allowing developers and third parties to audit the behavior of the system.

Open data: transparency and more diverse evidence

Properly validating AI models and systems, particularly in terms of fairness and robustness, requires representative and diverse datasets that reflect the reality of different populations and scenarios.

On the other hand, if only the companies that own a system have data to test it, we have to rely on their own internal evaluations. However, when open datasets and public testing standards exist, the community (universities, regulators, independent developers, etc.) can test the systems autonomously, thus functioning as an independent counterweight that serves the interests of society.

A concrete example was given by Meta (Facebook) when it released its Casual Conversations v2 dataset in 2023. It is an open dataset, obtained with informed consent, that collects videos from people from 7 countries (Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Vietnam, the Philippines and the USA), with 5,567 participants who provided attributes such as age, gender, language and skin tone.

Meta's objective with the publication was precisely to make it easier for researchers to evaluate the impartiality and robustness of AI systems in vision and voice recognition. By expanding the geographic provenance of the data beyond the U.S., this resource allows you to check if, for example, a facial recognition model works equally well with faces of different ethnicities, or if a voice assistant understands accents from different regions.

The diversity that open data brings also helps to uncover neglected areas in AI assessment. Researchers from Stanford's Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI) showed in the HELM (Holistic Evaluation of Language Models) project that many language models are not evaluated in minority dialects of English or in underrepresented languages, simply because there are no quality data in the most well-known benchmarks.

The community can identify these gaps and create new test sets to fill them (e.g., an open dataset of FAQs in Swahili to validate the behavior of a multilingual chatbot). In this sense, HELM has incorporated broader evaluations precisely thanks to the availability of open data, making it possible to measure not only the performance of the models in common tasks, but also their behavior in other linguistic, cultural and social contexts. This has contributed to making visible the current limitations of the models and to promoting the development of more inclusive and representative systems of the real world or models more adapted to the specific needs of local contexts, as is the case of the ALIA foundational model, developed in Spain.

In short, open data contributes to democratizing the ability to audit AI systems, preventing the power of validation from residing only in a few. They allow you to reduce costs and barriers as a small development team can test your model with open sets without having to invest great efforts in collecting their own data. This not only fosters innovation, but also ensures that local AI solutions from small businesses are also subject to rigorous validation standards.

The validation of applications based on generative AI is today an unquestionable necessity to ensure that these tools operate in tune with our values and expectations. It is not a trivial process, it requires new methodologies, innovative metrics and, above all, a culture of responsibility around AI. But the benefits are clear, a rigorously validated AI system will be more trustworthy, both for the individual user who, for example, interacts with a chatbot without fear of receiving a toxic response, and for society as a whole who can accept decisions based on these technologies knowing that they have been properly audited. And open data helps to cement this trust by fostering transparency, enriching evidence with diversity, and involving the entire community in the validation of AI systems.

Content prepared by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a key technology in multiple sectors, from health and education to industry and environmental management, not to mention the number of citizens who create texts, images or videos with this technology for their own personal enjoyment. It is estimated that in Spain more than half of the adult population has ever used an AI tool.

However, this boom poses challenges in terms of sustainability, both in terms of water and energy consumption and in terms of social and ethical impact. It is therefore necessary to seek solutions that help mitigate the negative effects, promoting efficient, responsible and accessible models for all. In this article we will address this challenge, as well as possible efforts to address it.

What is the environmental impact of AI?

In a landscape where artificial intelligence is all the rage, more and more users are wondering what price we should pay for being able to create memes in a matter of seconds.

To properly calculate the total impact of artificial intelligence, it is necessary to consider the cycles of hardware and software as a whole, as the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)indicates. That is, it is necessary to consider everything from raw material extraction, production, transport and construction of the data centre, management, maintenance and disposal of e-waste, to data collection and preparation, modelling, training, validation, implementation, inference, maintenance and decommissioning. This generates direct, indirect and higher-order effects:

- The direct impacts include the consumption of energy, water and mineral resources, as well as the production of emissions and e-waste, which generates a considerable carbon footprint.

- The indirect effects derive from the use of AI, for example, those generated by the increased use of autonomous vehicles.

- Moreover, the widespread use of artificial intelligence also carries an ethical dimension, as it may exacerbate existing inequalities, especially affecting minorities and low-income people. Sometimes the training data used are biased or of poor quality (e.g. under-representing certain population groups). This situation can lead to responses and decisions that favour majority groups.

Some of the figures compiled in the UN document that can help us to get an idea of the impact generated by AI include:

- A single request for information to ChatGPT consumes ten times more electricity than a query on a search engine such as Google, according to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

- Entering a single Large Language Model ( Large Language Models or LLM) generates approximately 300.000 kg of carbon dioxide emissions, which is equivalent to 125 round-trip flights between New York and Beijing, according to the scientific paper "The carbon impact of artificial intelligence".

- Global demand for AI water will be between 4.2 and 6.6 billion cubic metres by 2,027, a figure that exceeds the total consumption of a country like Denmark, according to the "Making AI Less "Thirsty": Uncovering and Addressing the Secret Water Footprint of AI Models" study.

Solutions for sustainable AI

In view of this situation, the UN itself proposes several aspects to which attention needs to be paid, for example:

- Search for standardised methods and parameters to measure the environmental impact of AI, focusing on direct effects, which are easier to measure thanks to energy, water and resource consumption data. Knowing this information will make it easier to take action that will bring substantial benefit.

- Facilitate the awareness of society, through mechanisms that oblige companies to make this information public in a transparent and accessible manner. This could eventually promote behavioural changes towards a more sustainable use of AI.

- Prioritise research on optimising algorithms, for energy efficiency. For example, the energy required can be minimised by reducing computational complexity and data usage. Decentralised computing can also be boosted, as distributing processes over less demanding networks avoids overloading large servers.

- Encourage the use of renewable energies in data centres, such as solar and wind power. In addition, companies need to be encouraged to undertake carbon offsetting practices.

In addition to its environmental impact, and as seen above, AI must also be sustainable from a social and ethical perspective. This requires:

- Avoid algorithmic bias: ensure that the data used represent the diversity of the population, avoiding unintended discrimination.

- Transparency in models: make algorithms understandable and accessible, promoting trust and human oversight.

- Accessibility and equity: develop AI systems that are inclusive and benefit underprivileged communities.

While artificial intelligence poses challenges in terms of sustainability, it can also be a key partner in building a greener planet. Its ability to analyse large volumes of data allows optimising energy use, improving the management of natural resources and developing more efficient strategies in sectors such as agriculture, mobility and industry. From predicting climate change to designing models to reduce emissions, AI offers innovative solutions that can accelerate the transition to a more sustainable future.

National Green Algorithms Programme

In response to this reality, Spain has launched the National Programme for Green Algorithms (PNAV). This is an initiative that seeks to integrate sustainability in the design and application of AI, promoting more efficient and environmentally responsible models, while promoting its use to respond to different environmental challenges.

The main goal of the NAPAV is to encourage the development of algorithms that minimise environmental impact from their conception. This approach, known as "Green by Design", implies that sustainability is not an afterthought, but a fundamental criterion in the creation of AI models. In addition, the programme seeks to promote research in sustainable IA, improve the energy efficiency of digital infrastructures and promote the integration of technologies such as the green blockchain into the productive fabric.

This initiative is part of the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan, the Spain Digital Agenda 2026 and the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy.. Objectives include the development of a best practice guide, a catalogue of efficient algorithms and a catalogue of algorithms to address environmental problems, the generation of an impact calculator for self-assessment, as well as measures to support awareness-raising and training of AI developers.

Its website functions as a knowledge space on sustainable artificial intelligence, where you can keep up to date with the main news, events, interviews, etc. related to this field. They also organise competitions, such as hackathons, to promote solutions that help solve environmental challenges.

The Future of Sustainable AI

The path towards more responsible artificial intelligence depends on the joint efforts of governments, business and the scientific community. Investment in research, the development of appropriate regulations and awareness of ethical AI will be key to ensuring that this technology drives progress without compromising the planet or society.

Sustainable AI is not only a technological challenge, but an opportunity to transform innovation into a driver of global welfare. It is up to all of us to progress as a society without destroying the planet.

Data is a fundamental resource for improving our quality of life because it enables better decision-making processes to create personalised products and services, both in the public and private sectors. In contexts such as health, mobility, energy or education, the use of data facilitates more efficient solutions adapted to people's real needs. However, in working with data, privacy plays a key role. In this post, we will look at how data spaces, the federated computing paradigm and federated learning, one of its most powerful applications, provide a balanced solution for harnessing the potential of data without compromising privacy. In addition, we will highlight how federated learning can also be used with open data to enhance its reuse in a collaborative, incremental and efficient way.

Privacy, a key issue in data management

As mentioned above, the intensive use of data requires increasing attention to privacy. For example, in eHealth, secondary misuse of electronic health record data could violate patients' fundamental rights. One effective way to preserve privacy is through data ecosystems that prioritise data sovereignty, such as data spaces. A dataspace is a federated data management system that allows data to be exchanged reliably between providers and consumers. In addition, the data space ensures the interoperability of data to create products and services that create value. In a data space, each provider maintains its own governance rules, retaining control over its data (i.e. sovereignty over its data), while enabling its re-use by consumers. This implies that each provider should be able to decide what data it shares, with whom and under what conditions, ensuring compliance with its interests and legal obligations.

Federated computing and data spaces

Data spaces represent an evolution in data management, related to a paradigm called federated computing, where data is reused without the need for data flow from data providers to consumers. In federated computing, providers transform their data into privacy-preserving intermediate results so that they can be sent to data consumers. In addition, this enables other Data Privacy-Enhancing Technologies(Privacy-Enhancing Technologies)to be applied. Federated computing aligns perfectly with reference architectures such as Gaia-X and its Trust Framework, which sets out the principles and requirements to ensure secure, transparent and rule-compliant data exchange between data providers and data consumers.

Federated learning

One of the most powerful applications of federated computing is federated machine learning ( federated learning), an artificial intelligence technique that allows models to be trained without centralising data. That is, instead of sending the data to a central server for processing, what is sent are the models trained locally by each participant.

These models are then combined centrally to create a global model. As an example, imagine a consortium of hospitals that wants to develop a predictive model to detect a rare disease. Every hospital holds sensitive patient data, and open sharing of this data is not feasible due to privacy concerns (including other legal or ethical issues). With federated learning, each hospital trains the model locally with its own data, and only shares the model parameters (training results) centrally. Thus, the final model leverages the diversity of data from all hospitals without compromising the individual privacy and data governance rules of each hospital.

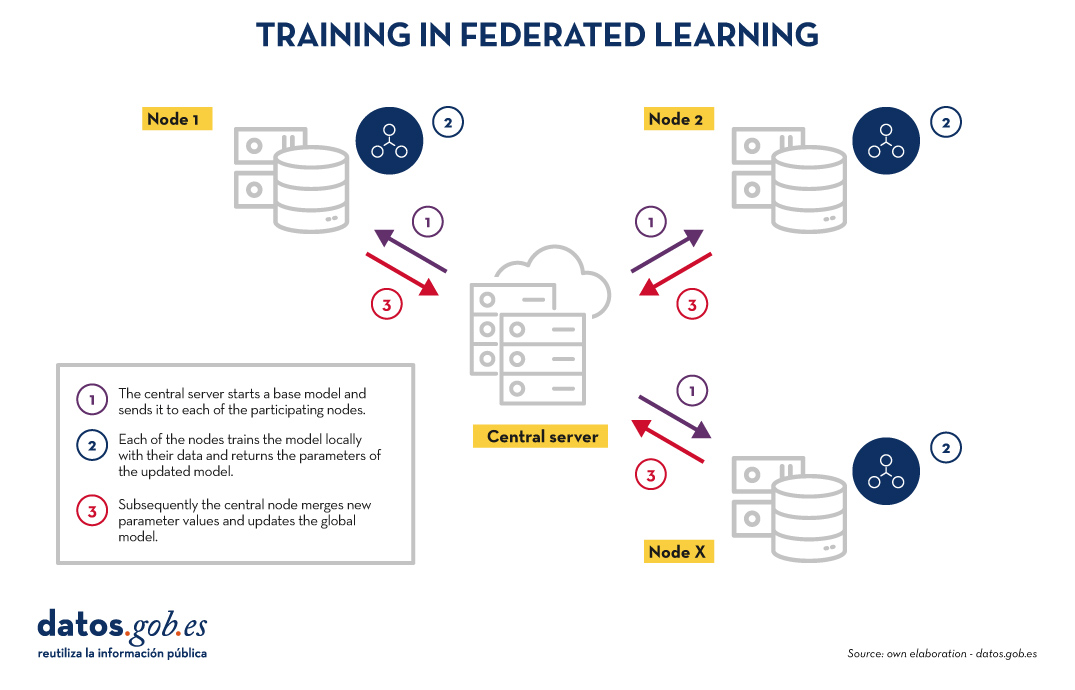

Training in federated learning usually follows an iterative cycle:

- A central server starts a base model and sends it to each of the participating distributed nodes.

- Each node trains the model locally with its data.

- Nodes return only the parameters of the updated model, not the data (i.e. data shuttling is avoided).

- The central server aggregates parameter updates, training results at each node and updates the global model.

- The cycle is repeated until a sufficiently accurate model is achieved.

Figure 1. Visual representing the federated learning training process. Own elaboration

This approach is compatible with various machine learning algorithms, including deep neural networks, regression models, classifiers, etc.

Benefits and challenges of federated learning

Federated learning offers multiple benefits by avoiding data shuffling. Below are the most notable examples:

- Privacy and compliance: by remaining at source, data exposure risks are significantly reduced and compliance with regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is facilitated.

- Data sovereignty: Each entity retains full control over its data, which avoids competitive conflicts.

- Efficiency: avoids the cost and complexity of exchanging large volumes of data, speeding up processing and development times.

- Trust: facilitates frictionless collaboration between organisations.

There are several use cases in which federated learning is necessary, for example:

- Health: Hospitals and research centres can collaborate on predictive models without sharing patient data.

- Finance: banks and insurers can build fraud detection or risk-sharing analysis models, while respecting the confidentiality of their customers.

- Smart tourism: tourist destinations can analyse visitor flows or consumption patterns without the need to unify the databases of their stakeholders (both public and private).

- Industry: Companies in the same industry can train models for predictive maintenance or operational efficiency without revealing competitive data.

While its benefits are clear in a variety of use cases, federated learning also presents technical and organisational challenges:

- Data heterogeneity: Local data may have different formats or structures, making training difficult. In addition, the layout of this data may change over time, which presents an added difficulty.

- Unbalanced data: Some nodes may have more or higher quality data than others, which may skew the overall model.

- Local computational costs: Each node needs sufficient resources to train the model locally.

- Synchronisation: the training cycle requires good coordination between nodes to avoid latency or errors.

Beyond federated learning

Although the most prominent application of federated computing is federated learning, many additional applications in data management are emerging, such as federated data analytics (federated analytics). Federated data analysis allows statistical and descriptive analyses to be performed on distributed data without the need to move the data to the consumers; instead, each provider performs the required statistical calculations locally and only shares the aggregated results with the consumer according to their requirements and permissions. The following table shows the differences between federated learning and federated data analysis.

|

Criteria |

Federated learning |

Federated data analysis |

|

Target |

Prediction and training of machine learning models. | Descriptive analysis and calculation of statistics. |

| Task type | Predictive tasks (e.g. classification or regression). | Descriptive tasks (e.g. means or correlations). |

| Example | Train models of disease diagnosis using medical images from various hospitals. | Calculation of health indicators for a health area without moving data between hospitals. |

| Expected output | Modelo global entrenado. | Resultados estadísticos agregados. |

| Nature | Iterativa. | Directa. |

| Computational complexity | Alta. | Media. |

| Privacy and sovereignty | High | Average |

| Algorithms | Machine learning. | Statistical algorithms. |

Figure 1. Comparative table. Source: own elaboration

Federated learning and open data: a symbiosis to be explored

In principle, open data resolves privacy issues prior to publication, so one would think that federated learning techniques would not be necessary. Nothing could be further from the truth. The use of federated learning techniques can bring significant advantages in the management and exploitation of open data. In fact, the first aspect to highlight is that open data portals such as datos.gob.es or data.europa.eu are federated environments. Therefore, in these portals, the application of federated learning on large datasets would allow models to be trained directly at source, avoiding transfer and processing costs. On the other hand, federated learning would facilitate the combination of open data with other sensitive data without compromising the privacy of the latter. Finally, the nature of a wide variety of open data types is very dynamic (such as traffic data), so federated learning would enable incremental training, automatically considering new updates to open datasets as they are published, without the need to restart costly training processes.

Federated learning, the basis for privacy-friendly AI

Federated machine learning represents a necessary evolution in the way we develop artificial intelligence services, especially in contexts where data is sensitive or distributed across multiple providers. Its natural alignment with the concept of the data space makes it a key technology to drive innovation based on data sharing, taking into account privacy and maintaining data sovereignty.

As regulation (such as the European Health Data Space Regulation) and data space infrastructures evolve, federated learning, and other types of federated computing, will play an increasingly important role in data sharing, maximising the value of data, but without compromising privacy. Finally, it is worth noting that, far from being unnecessary, federated learning can become a strategic ally to improve the efficiency, governance and impact of open data ecosystems.

Jose Norberto Mazón, Professor of Computer Languages and Systems at the University of Alicante. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Data science is all the rage. Professions related to this field are among the most in-demand, according to the latest study ‘Posiciones y competencias más Demandadas 2024’, carried out by the Spanish Association of Human Resources Managers. In particular, there is a significant demand for roles related to data management and analysis, such as Data Analyst, Data Engineer and Data Scientist. The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the need to make data-driven decisions are driving the integration of this type of professionals in all sectors.

Universities are aware of this situation and therefore offer a large number of degrees, postgraduate courses and also summer courses, both for beginners and for those who want to broaden their knowledge and explore new technological trends. Here are just a few examples of some of them. These courses combine theory and practice, allowing you to discover the potential of data.

1. Data Analysis and Visualisation: Practical Statistics with R and Artificial Intelligence. National University of Distance Education (UNED).

This seminar offers comprehensive training in data analysis with a practical approach. Students will learn to use the R language and the RStudio environment, with a focus on visualisation, statistical inference and its use in artificial intelligence systems. It is aimed at students from related fields and professionals from various sectors (such as education, business, health, engineering or social sciences) who need to apply statistical and AI techniques, as well as researchers and academics who need to process and visualise data.

- Date and place: from 25 to 27 June 2025 in online and face-to-face mode (in Plasencia).

2. Big Data. Data analysis and automatic learning with Python. Complutense University.

Thanks to this training, students will be able to acquire a deep understanding of how data is obtained, managed and analysed to generate valuable knowledge for decision making. Among other issues, the life cycle of a Big Data project will be shown, including a specific module on open data. In this case, the language chosen for the training will be Python. No previous knowledge is required to attend: it is open to university students, teachers, researchers and professionals from any sector with an interest in the subject.

- Date and place: 30 June to 18 July 2025 in Madrid.

3. Challenges in Data Science: Big Data, Biostatistics, Artificial Intelligence and Communications. University of Valencia.

This programme is designed to help participants understand the scope of the data-driven revolution. Integrated within the Erasmus mobility programmes, it combines lectures, group work and an experimental lab session, all in English. Among other topics, open data, open source tools, Big Data databases, cloud computing, privacy and security of institutional data, text mining and visualisation will be discussed.

- Date and place: From 30 June to 4 July at two venues in Valencia. Note: Places are currently full, but the waiting list is open.

4. Digital twins: from simulation to intelligent reality. University of Castilla-La Mancha.

Digital twins are a fundamental tool for driving data-driven decision-making. With this course, students will be able to understand the applications and challenges of this technology in various industrial and technological sectors. Artificial intelligence applied to digital twins, high performance computing (HPC) and digital model validation and verification, among others, will be discussed. It is aimed at professionals, researchers, academics and students interested in the subject.

- Date and place: 3 and 4 July in Albacete.

5. Health Geography and Geographic Information Systems: practical applications. University of Zaragoza.

The differential aspect of this course is that it is designed for those students who are looking for a practical approach to data science in a specific sector such as health. It aims to provide theoretical and practical knowledge about the relationship between geography and health. Students will learn how to use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to analyse and represent disease prevalence data. It is open to different audiences (from students or people working in public institutions and health centres, to neighbourhood associations or non-profit organisations linked to health issues) and does not require a university degree.

- Date and place: 7-9 July 2025 in Zaragoza.

6. Deep into data science. University of Cantabria.

Aimed at scientists, university students (from second year onwards) in engineering, mathematics, physics and computer science, this intensive course aims to provide a complete and practical vision of the current digital revolution. Students will learn about Python programming tools, machine learning, artificial intelligence, neural networks or cloud computing, among other topics. All topics are introduced theoretically and then experimented with in laboratory practice.

- Date and place: from 7 to 11 July 2025 in Camargo.

7. Advanced Programming. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

Taught entirely in English, the aim of this course is to improve students' programming skills and knowledge through practice. To do so, two games will be developed in two different languages, Java and Python. Students will be able to structure an application and program complex algorithms. It is aimed at students of any degree (mathematics, physics, engineering, chemistry, etc.) who have already started programming and want to improve their knowledge and skills.

- Date and place: 14 July to 1 August 2025, at a location to be defined.

8. Data visualisation and analysis with R. Universidade de Santiago de Compostela.

This course is aimed at beginners in the subject. It will cover the basic functionalities of R with the aim that students acquire the necessary skills to develop descriptive and inferential statistical analysis (estimation, contrasts and predictions). Search and help tools will also be introduced so that students can learn how to use them independently.

- Date and place: from 14 to 24 July 2025 in Santiago de Compostela.

9. Fundamentals of artificial intelligence: generative models and advanced applications. International University of Andalusia.

This course offers a practical introduction to artificial intelligence and its main applications. It covers concepts related to machine learning, neural networks, natural language processing, generative AI and intelligent agents. The language used will be Python, and although the course is introductory, it will be best used if the student has a basic knowledge of programming. It is therefore aimed primarily at undergraduate and postgraduate students in technical areas such as engineering, computer science or mathematics, professionals seeking to acquire AI skills to apply in their industries, and teachers and researchers interested in updating their knowledge of the state of the art in AI.

- Date and place: 19-22 August 2025, in Baeza.

10. IA Generative AI to innovate in the company: real cases and tools for its implementation. University of the Basque Country.

This course, open to the general public, aims to help understand the impact of generative AI in different sectors and its role in digital transformation through the exploration of real cases of application in companies and technology centres in the Basque Country. This will combine talks, panel discussions and a practical session focused on the use of generative models and techniques such as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and Fine-Tuning.

- Date and place: 10 September in San Sebastian.

Investing in technology training during the summer is not only an excellent way to strengthen skills, but also to connect with experts, share ideas and discover opportunities for innovation. This selection is just a small sample of what's on offer. If you know of any other courses you would like to share with us, please leave a comment or write to dinamizacion@datos.gob.es

Open data is a fundamental fuel for contemporary digital innovation, creating information ecosystems that democratise access to knowledge and foster the development of advanced technological solutions.

However, the mere availability of data is not enough. Building robust and sustainable ecosystems requires clear regulatory frameworks, sound ethical principles and management methodologies that ensure both innovation and the protection of fundamental rights. Therefore, the specialised documentation that guides these processes becomes a strategic resource for governments, organisations and companies seeking to participate responsibly in the digital economy.

In this post, we compile recent reports, produced by leading organisations in both the public and private sectors, which offer these key orientations. These documents not only analyse the current challenges of open data ecosystems, but also provide practical tools and concrete frameworks for their effective implementation.

State and evolution of the open data market

Knowing what it looks like and what changes have occurred in the open data ecosystem at European and national level is important to make informed decisions and adapt to the needs of the industry. In this regard, the European Commission publishes, on a regular basis, a Data Markets Report, which is updated regularly. The latest version is dated December 2024, although use cases exemplifying the potential of data in Europe are regularly published (the latest in February 2025).

On the other hand, from a European regulatory perspective, the latest annual report on the implementation of the Digital Markets Act (DMA)takes a comprehensive view of the measures adopted to ensure fairness and competitiveness in the digital sector. This document is interesting to understand how the regulatory framework that directly affects open data ecosystems is taking shape.

At the national level, the ASEDIE sectoral report on the "Data Economy in its infomediary scope" 2025 provides quantitative evidence of the economic value generated by open data ecosystems in Spain.

The importance of open data in AI

It is clear that the intersection between open data and artificial intelligence is a reality that poses complex ethical and regulatory challenges that require collaborative and multi-sectoral responses. In this context, developing frameworks to guide the responsible use of AI becomes a strategic priority, especially when these technologies draw on public and private data ecosystems to generate social and economic value. Here are some reports that address this objective:

- Generative IA and Open Data: Guidelines and Best Practices: the U.S. Department of Commerce. The US government has published a guide with principles and best practices on how to apply generative artificial intelligence ethically and effectively in the context of open data. The document provides guidelines for optimising the quality and structure of open data in order to make it useful for these systems, including transparency and governance.

- Good Practice Guide for the Use of Ethical Artificial Intelligence: This guide demonstrates a comprehensive approach that combines strong ethical principles with clear and enforceable regulatory precepts.. In addition to the theoretical framework, the guide serves as a practical tool for implementing AI systems responsibly, considering both the potential benefits and the associated risks. Collaboration between public and private actors ensures that recommendations are both technically feasible and socially responsible.

- Enhancing Access to and Sharing of Data in the Age of AI: this analysis by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) addresses one of the main obstacles to the development of artificial intelligence: limited access to quality data and effective models. Through examples, it identifies specific strategies that governments can implement to significantly improve data access and sharing and certain AI models.

- A Blueprint to Unlock New Data Commons for AI: Open Data Policy Lab has produced a practical guide that focuses on the creation and management of data commons specifically designed to enable cases of public interest artificial intelligence use. The guide offers concrete methodologies on how to manage data in a way that facilitates the creation of these data commons, including aspects of governance, technical sustainability and alignment with public interest objectives.

- Practical guide to data-driven collaborations: the Data for Children Collaborative initiative has published a step-by-step guide to developing effective data collaborations, with a focus on social impact. It includes real-world examples, governance models and practical tools to foster sustainable partnerships.

In short, these reports define the path towards more mature, ethical and collaborative data systems. From growth figures for the Spanish infomediary sector to European regulatory frameworks to practical guidelines for responsible AI implementation, all these documents share a common vision: the future of open data depends on our ability to build bridges between the public and private sectors, between technological innovation and social responsibility.

AI systems designed to assist us from the first dives to the final bibliography.

One of the missions of contemporary artificial intelligence is to help us find, sort and digest information, especially with the help of large language models. These systems have come at a time when we most need to manage knowledge that we produce and share en masse, but then struggle to embrace and consume. Its value lies in finding the ideas and data we need quickly, so that we can devote our effort and time to thinking or, in other words, start climbing the ladder a rung or two ahead.

AI-based systems academic research as well as trend studies in the business world. AI analytics tools can analyse thousands of papers to show us which authors collaborate with each other or how topics are grouped, creating an interactive, filterable map of the literature on demand. The Generative AI,the long-awaited one, can start from a research question and return useful sub-content as a synthesis or a contrast of approaches. The first shows us the terrain on the map, while the second suggests where we can move forward.

Practical tools

Starting with the more analytical ones and leaving the mixed or generative ones for last, we go through four practical research tools that integrate AI as a functionality, and one extra ball.

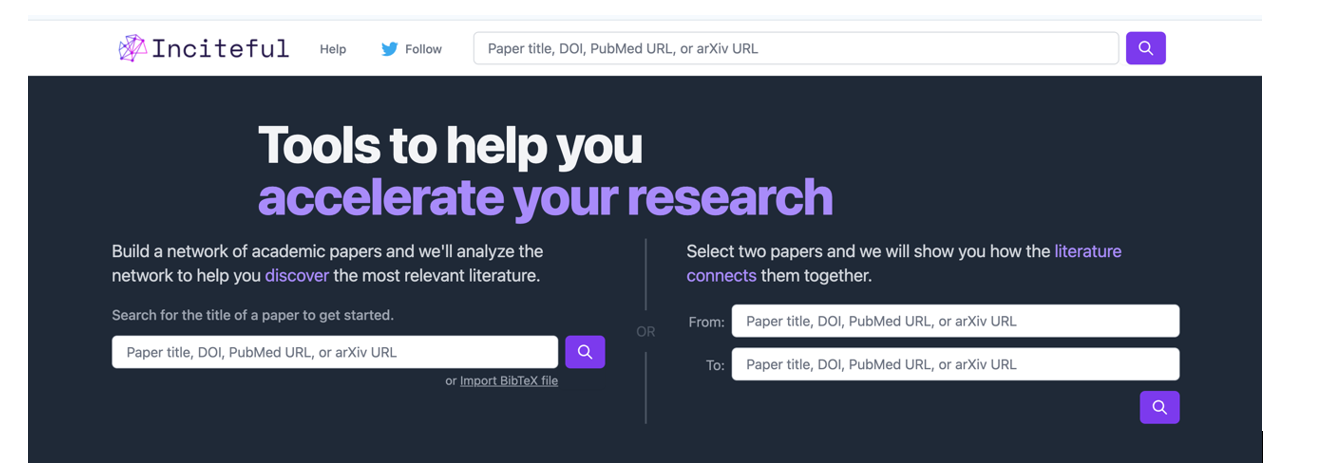

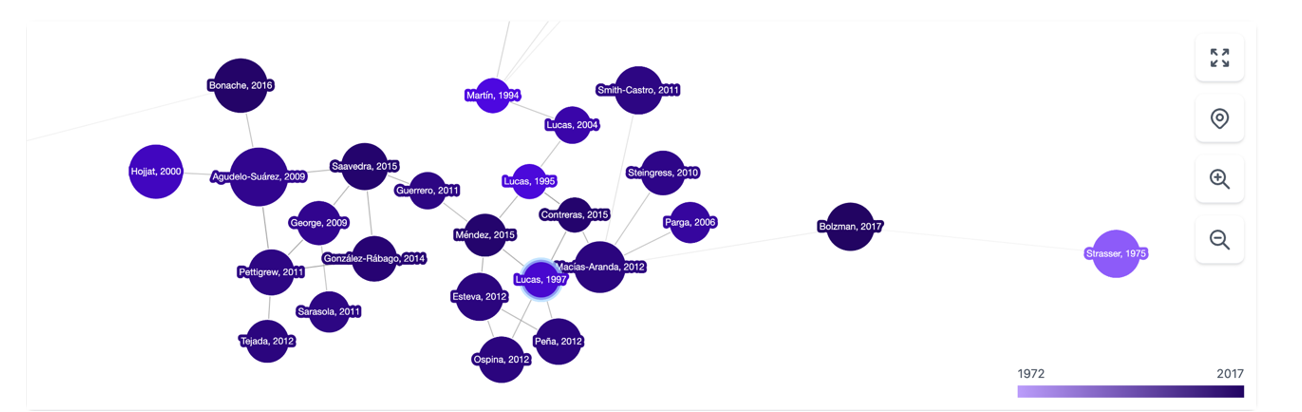

It is a tool based above all on the connection between authors, topics and articles, which shows us networks of citations and allows us to create the complete graph of the literature around a topic. As a starting point, Inciteful asks for the title or URL of a paper, but you can also simply search by your research topic. There is also the possibility to enter the data of two items, to show how they are connected to each other.

Figure 1. Screenshot in Inciteful: initial search screen and connection between papers.

Figure 2. Screenshot on Inciteful: network of nodes with articles and authors.

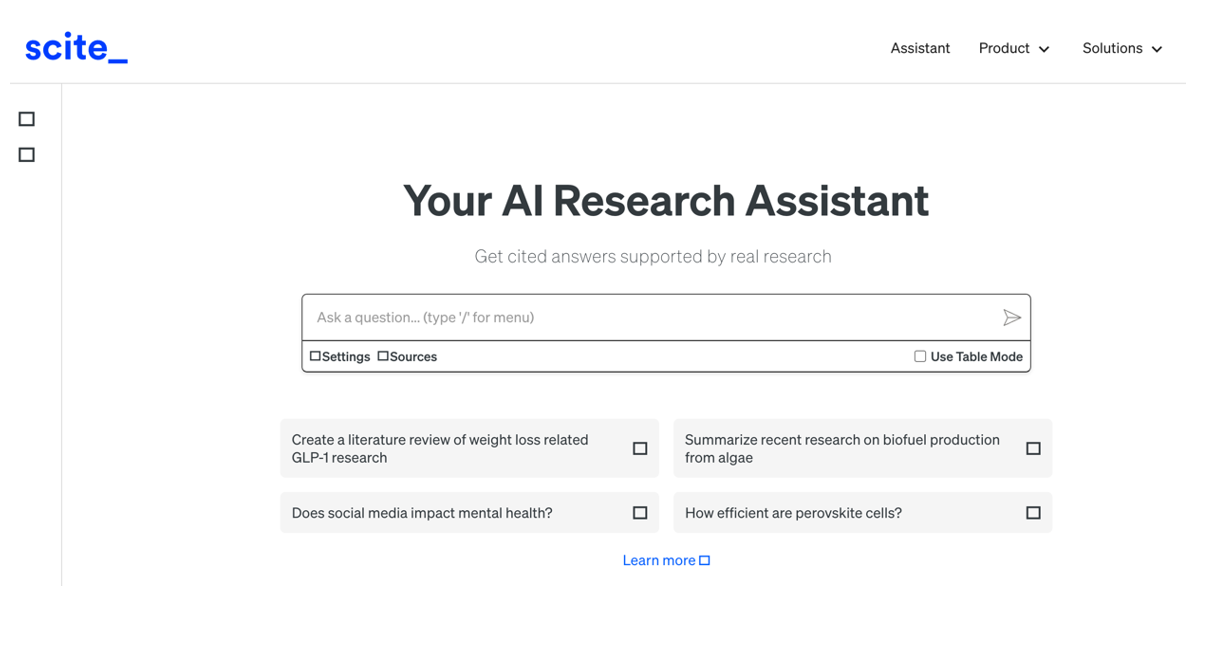

In Scite, AI integration is more obvious and practical: given a question, it creates a single summary answer by combining information from all references. The tool analyses the semantics of the papers to extract the nature of each quote: how many quotes support it ( check symbol), question it (question mark) or just mention it (slash). This allows us to do something as valuable as adding context to the impact metrics of an article in our bibliography.

Figure 3. Screenshot in Scite: initial search screen.

Figure 4. Screenshot in Scite: citation assessment of an article.

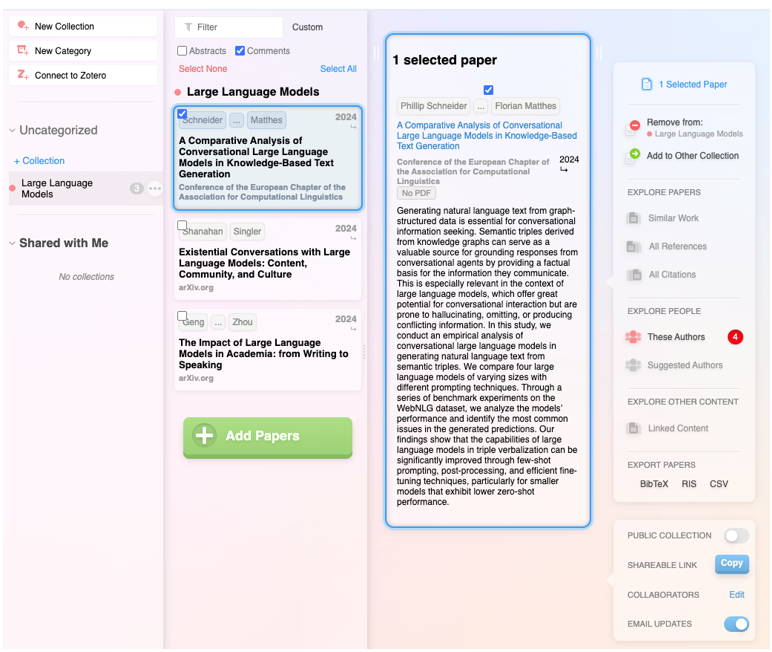

In addition to integrating the functionalities of the previous ones, it is a very complete digital product that not only allows you to navigate from paper to paper in the form of a visual network, but also makes it possible to set up alerts on a topic or an author you follow and create lists of papers. In addition, the system itself suggests which other papers you might be interested in, all in the style of a recommendation system like Spotify or Netflix. It also allows you to make public lists, as in Google Maps, and to work collaboratively with other users.

Figure 5. Screenshot on Research Rabbit: customised list of items.

It has the backing of the British government, Stanford University and NASA, and is based entirely on generative AI. Its flagship functionality is the ability to ask direct questions to a paper or a collection of articles, and finally get a targeted report with all the references. But actually, the most striking feature is the ability to improve the user's initial question: the tool instantly evaluates the quality of the question and makes suggestions to make it more accurate or interesting.

Figure 6. Screenshot in Elicit: suggestions for improvement for the initial question..

Extra ball: Consensus.

What started as a humble customised GPT within the Plus version of ChatGPT has turned into a full-fledged digital research product. Based on a question, attempt to synthesise the scientific consensus on that topic, indicating whether there is agreement or disagreement between studies. In a simple and visual way it shows how many support a statement, how many doubt it and which conclusions predominate, as well as providing a short report for quick guidance.

Figure 7. Screenshot on Consensus: impact metrics from a question

The depth button

In recent months, a new functionality has appeared on the platforms of large commercial language models focused on in-depth research. Specifically, it is a button with the same name, "in-depth research" or "deep research", which can already be found in ChatGPT, Plus version (with limited requests) or Pro, and in Gemini Advanced, although they promise that it will gradually be opened to free use and allow some tests without cost.

Figure 8. Screenshot in ChatGPT Plus: In-depth research button.

Figure 9. Screenshot in Gemini Advanced: Deep Research button.

This option, which must be activated before launching the prompt, works as a shortcut: the model generates a synthetic and organised report on the topic, gathering key information, data and context. Before starting the investigation, the system may ask additional questions to better focus the search.

Figure 10. Screenshot in ChatGPT Plus: questions to narrow down the research

It should be noted that, once these questions have been answered, the system initiates a process that may take much longer than a normal response. In particular, in ChatGPT Plus it can take up to 10 minutes. A progress bar indicates progress.

Figure 11. Screenshot in ChatGPT Plus: Research start and progress bar

What we get now is a comprehensive, considerably accurate report, including examples and links that can quickly put us on the track of what we are looking for.

Figure 12: Screenshot of ChatGPT Plus: research result (excerpt).

Closure

The tools designed to apply AI for research are neither infallible nor definitive, and may still be subject to errors and hallucinations, but research with AI is already a radically different process from research without it. Assisted search is, like almost everything else when it comes to AI, about not dismissing as imperfect what can be useful, spending some time trying out new uses that can save us many hours later on, and focusing on what it can do to keep our focus on the next steps.

Content prepared by Carmen Torrijos, expert in AI applied to language and communication. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The Work Trends 2024 Index on the State of Artificial Intelligence in the Workplace and reports from T-Systems and InfoJobs indicate that 78% of workers in Spain use their own AI tools in the workplace. This figure rises to 80% in medium-sized companies. In addition, 1 in 3 workers (32%) use AI tools in their day-to-day work. 75% of knowledge workers use generative AI tools, and almost half have started doing so in the last six months. Interestingly, the generation gap is narrowing in this area. While 85% of Generation Z employees (18-28 years old) use personalised AI, it turns out that more than 70% of baby boomers (58+) also use these tools. In fact, this trend seems to be confirmed by different approaches.

| Títle of the study | Source |

|---|---|

| 2024 Work Trend Index: AI at work is here. Now comes the hard part | Microsoft, LinkedIn |

| 2024 AI Adoption and Risk Report | Cyberhaven Labs |

| Generative AI''s fast and furious entry into Switzerland | Deloitte Switzerland |

| Bring Your Own AI: Balance Rewards and Risks (Webinar) | MITSloan |

| Lin, L. and Parker, K. (2025) U.S. workers are more worried than hopeful about future AI use in the Workplace | Pew Research Center |

Figure 1. References on BYOAI

This phenomenon has been called BYOAI (Bring Your Own AI ), for short. It is characterised by the fact that the person employed usually uses some kind of open source solution such as ChatGPT. The organisation has not contracted the service, the registration has been made privately by the user and the provider obviously assumes no legal responsibility. If, for example, the possibilities offered by Notebook, Perplexity or DeepSeek are used, it is perfectly possible to upload confidential or protected documents.

On the other hand, this coincides, according to data from EuroStat, with the adoption of AI in the corporate sector. By 2024, 13.5% of European companies (with 10 or more employees) were using some form of AI technology, a figure that rises to 41% in large companies and is particularly high in sectors such as information and communication (48.7%), professional, scientific and technical services (30.5%). The trend towards AI adoption in the public sector is also growing due not only to global trends, but probably to the adoption of AI strategies and the positive impact of Next Generation funds.

The legal duty of AI literacy

In this context, questions immediately arise. The first concern the phenomenon of unauthorised use by employed persons: Has the data protection officer or the security officer issued a report to the management of the organisation? Has this type of use been authorised? Was the matter discussed at a meeting of the Security Committee? Has an information circular been issued defining precisely the applicable rules? But alongside these emerge others of a more general nature: What level of education do people have? Are they able to issue reports or make decisions using such tools?

The EU Regulation on Artificial Intelligence (RIA) has rightly established a duty of AI literacy imposed on the providers and deployers of such systems. They are responsible for taking measures to ensure that, to the greatest extent possible, their staff and others who are responsible for the operation and use of AI systems on their behalf have a sufficient level of AI literacy. This requires taking into account their expertise, experience, education and training. Training should be integrated into the intended context of use of the AI systems and be tailored to the profile of the individuals or groups in which the systems will be used.

Unlike in the General Data Protection Regulation, here the obligation is formulated in an express and imperative manner.. There is no direct reference to this matter in the GDPR, except in defining as a function of the data protection officer the training of staff involved in processing operations. This need can also be deduced from the obligation of the processor to ensure that persons authorised to process personal data are aware of their duty of confidentiality. It is obvious that the duty of proactive accountability, data protection by design and by default and risk management lead to the training of users of information systems. However, the fact is that the way in which this training is deployed is not always appropriate. In many organisations it is either non-existent, voluntary or based on the signing of a set of security obligations when taking up a job.

In the field of artificial intelligence-based information systems, the obligation to train is non-negotiable and imperative. The RIA provides for very high fines specified in the Bill for the good use and governance of Artificial Intelligence. When the future law is passed, it will be a serious breach of Article 26.2 of the RIA, concerning the need to entrust the human supervision of the system to persons with adequate competence, training and authority.

Benefits of AI training