The evolution of generative AI has been dizzying: from the first great language models that impressed us with their ability to reproduce human reading and writing, through the advanced RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) techniques that quantitatively improved the quality of the responses provided and the emergence of intelligent agents, to an innovation that redefines our relationship with technology: Computer use.

At the end of April 2020, just one month after the start of an unprecedented period of worldwide home confinement due to the SAR-Covid19 global pandemic, we spread from datos.gob.es the large GPT-2 and GPT-3 language models. OpenAI, founded in 2015, had presented almost a year earlier (February 2019) a new language model that was able to generate written text virtually indistinguishable from that created by a human. GPT-2 had been trained on a corpus (set of texts prepared to train language models) of about 40 GB (Gigabytes) in size (about 8 million web pages), while the latest family of models based on GPT-4 is estimated to have been trained on TB (Terabyte) sized corpora; a thousand times more.

In this context, it is important to talk about two concepts:

- LLLMs (Large Language Models ): are large-scale language models, trained on vast amounts of data and capable of performing a wide range of linguistic tasks. Today, we have countless tools based on these LLMs that, by field of expertise, are able to generate programming code, ultra-realistic images and videos, and solve complex mathematical problems. All major companies and organisations in the digital-technology sector have embarked on integrating these tools into their different software and hardware products, developing use cases that solve or optimise specific tasks and activities that previously required a high degree of human intervention.

- Agents: The user experience with artificial intelligence models is becoming more and more complete, so that we can ask our interface not only to answer our questions, but also to perform complex tasks that require integration with other IT tools. For example, we not only ask a chatbot for information on the best restaurants in the area, but we also ask them to search for table availability for specific dates and make a reservation for us. This extended user experience is what artificial intelligence agentsprovide us with. Based on the large language models, these agents are able to interact with the outside world (to the model) and "talk" to other services via APIs and programming interfaces prepared for this purpose.

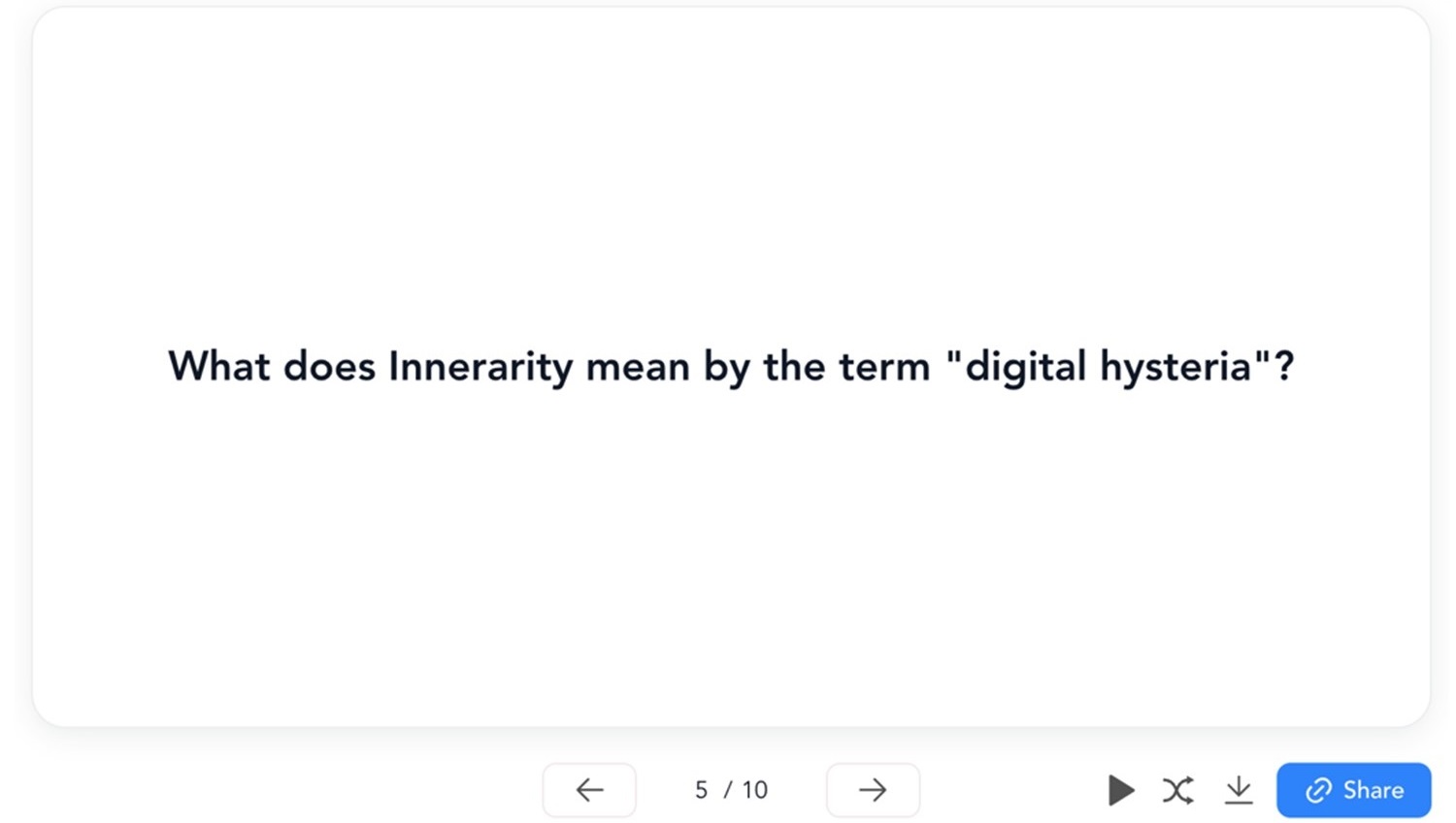

Computer use

However, the ability of agents to perform actions autonomously depends on two key elements: on the one hand, their concrete programming - the functionality that has been programmed or configured for them; on the other hand, the need for all other programmes to be ready to "talk" to these agents. That is, their programming interfaces must be ready to receive instructions from these agents. For example, the restaurant reservation application has to be prepared, not only to receive forms filled in by a human, but also requests made by an agent that has been previously invoked by a human using natural language. This fact imposes a limitation on the set of activities and/or tasks that we can automate from a conversational interface. In other words, the conversational interface can provide us with almost infinite answers to the questions we ask it, but it is severely limited in its ability to interact with the outside world due to the lack of preparation of the rest of computer applications.

This is where Computer use comes in. With the arrival of the Claude 3.5 Sonnet model, Anthropic has introduced Computer use, a beta capability that allows AI to interact directly with graphical user interfaces.

How does Computer use work?

Claude can move your computer cursor as if it were you, click buttons and type text, emulating the way humans operate a computer. The best way to understand how Computer use works in practice is to see it in action. Here is a link directly to the YouTube channel of the specific Computer use section.

Figure 1. Screenshot from Anthropic's YouTube channel, Computer use specific section.

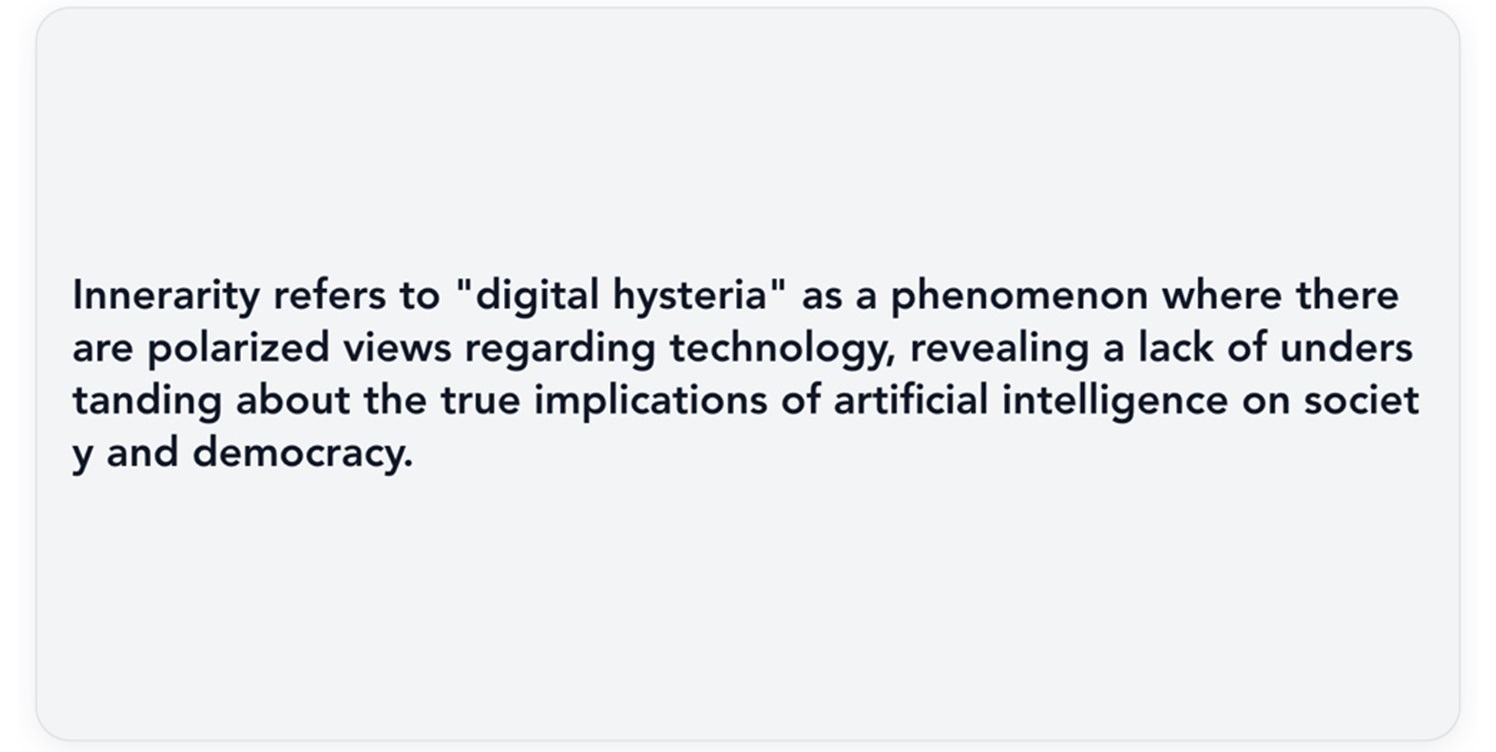

Would you like to try it?

If you've made it this far, you can't miss out without trying it with your own hands.

Here is a simple guide to testing Computer use in an isolated environment. It is important to take into account the security recommendations that Antrophic proposes in its Computer use guidelines. This feature of the Claude Sonet model can perform actions on a computer and this can be potentially dangerous, so it is recommended to carefully review the security warning of Computer use.

All official developer documentation can be found in the antrophic's official Github repository. In this post, we have chosen to run Computer use in a Docker container environment. It is the easiest and safest way to test it. If you don't already have it, you can follow the simple official guidelines to pre-install it on your system.

To reproduce this test we propose to follow this script step by step:.

- Anthropic API Key. To interact with Claude Sonet you need an Anthropic account which you can create for free here. Once inside, you can go to the API Keys section and create a new one for your test

- Once you have your API Key, you must run this command in your terminal, substituting your key where it says "%your_api_key%":

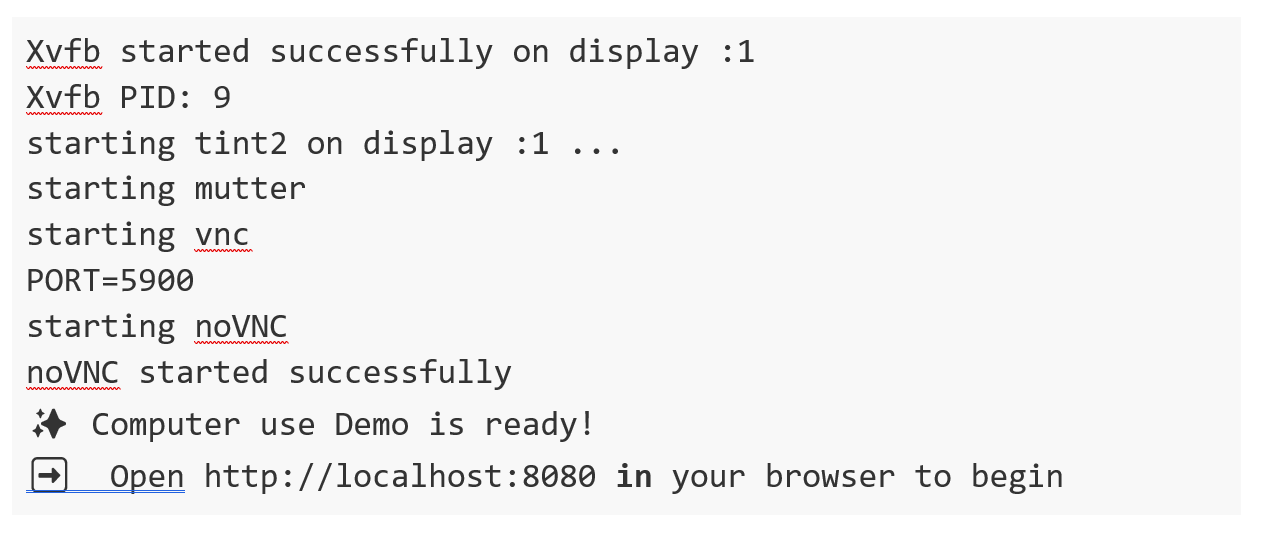

3. If everything went well, you will see these messages in your terminal and now you just have to open your browser and type this url in the navigation bar: htttp://localhost:8080/.

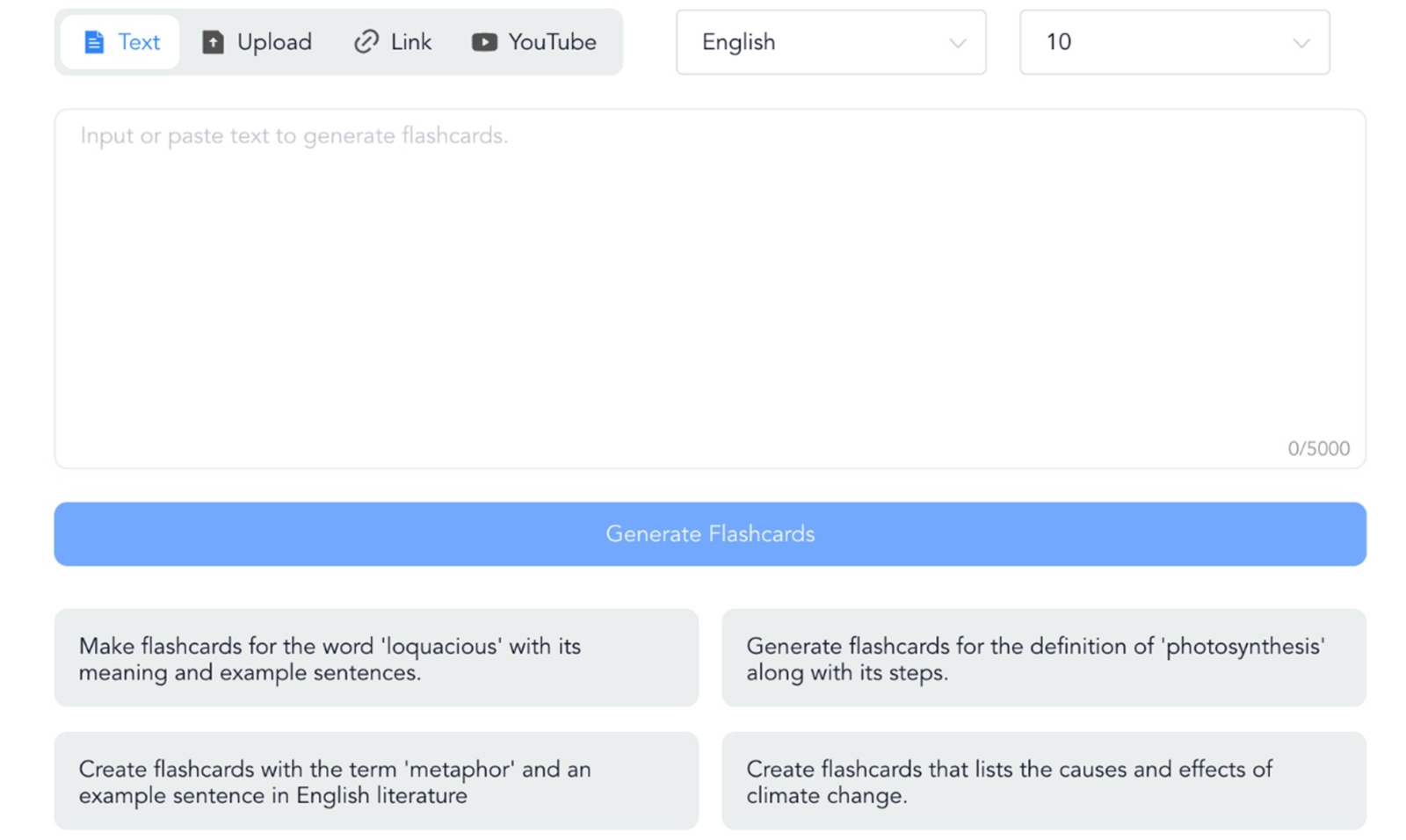

You will see your interface open:

Figure 2. Computer use interface.

You can now go to explore how Computer use works. We suggest the following prompt to get you started:

We suggest you start small. For example, ask them to open a browser and search for something. You can also ask him to give you information about your computer or operating system. Gradually, you can ask for more complex tasks. We have tested this prompt and after several trials we have managed to get Computer use to perform the complete task.

Open a browser, navigate to the datos.gob.es catalogue, use the search engine to locate a dataset on: Public security. Traffic accidents. 2014; Locate the file in csv format; download and open it with free Office.

Potential uses in data platforms such as datos.gob.es

In view of this first experimental version of Computer use, it seems that the potential of the tool is very high. We can imagine how many more things we can do thanks to this tool. Here are some ideas:

- We could ask the system to perform a complete search of datasets related to a specific topic and summarise the main results in a document. In this way, if for example we write an article on traffic data in Spain, we could unattended obtain a list of the main open datasets of traffic data in Spain in the datos.gob.es catalogue.

- In the same way, we could request a summary in the same way, but in this case, not of dataset, but of platform items.

- A slightly more sophisticated example would be to ask Claude, through the conversational interface of Computer use, to make a series of calls to the data API.gob.es to obtain information from certain datasets programmatically. To do this, we open a browser and log into an application such as Postman (remember at this point that Computer use is in experimental mode and does not allow us to enter sensitive data such as user credentials on web pages). We can then ask you to search for information about the datos.gob.es API and execute an http call, taking advantage of the fact that this API does not require authentication.

Through these simple examples, we hope that we have introduced you to a new application of generative AI and that you have understood the paradigm shift that this new capability represents. If the machine is able to emulate the use of a computer as we humans do, unimaginable new opportunities will open up in the coming months.

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, expert in Digital Transformation and Innovation. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The enormous acceleration of innovation in artificial intelligence (AI) in recent years has largely revolved around the development of so-called "foundational models". Also known as Large [X] Models (Large [X] Models or LxM), Foundation Models, as defined by the Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM) of the Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence's (HAI) Stanford University's models that have been trained on large and highly diverse datasets and can be adapted to perform a wide range of tasks using techniques such as fine-tuning (fine-tuning).

It is precisely this versatility and adaptability that has made foundational models the cornerstone of the numerous applications of artificial intelligence being developed, since a single base architecture can be used across a multitude of use cases with limited additional effort.

Types of foundational models

The "X" in LxM can be replaced by several options depending on the type of data or tasks for which the model is specialised. The best known by the public are the LLM (Large Language Models), which are at the basis of applications such as ChatGPT or Gemini, and which focus on natural language understanding and generation.. LVMs (Large Vision Models), such as DINOv2 or CLIP, are designed tointerpret images and videos, recognise objects or generate visual descriptions.. There are also models such as Operator or Rabbit R1 that fall into the LAM (Large Action Models) category and are aimed atexecuting actions from complex instructions..

As regulations have emerged in different parts of the world, so have other definitions that seek to establish criteria and responsibilities for these models to foster confidence and security. The most relevant definition for our context is that set out in the European Union AI Regulation (AI Act), which calls them "general-purpose AI models" and distinguishes them by their "ability to competently perform a wide variety of discrete tasks" and because they are "typically trained using large volumes of data and through a variety of methods, such as self-supervised, unsupervised or reinforcement learning".

Foundational models in Spanish and other co-official languages

Historically, English has been the dominant language in the development of large AI models, to the extent that around 90% of the training tokens of today's large models are drawn from English texts. It is therefore logical that the most popular models, for example OpenAI's GPT family, Google's Gemini or Meta's Llama, are more competent at responding in English and perform less well when used in other languages such as Spanish.

Therefore, the creation of foundational models in Spanish, such as ALIA, is not simply a technical or research exercise, but a strategic move to ensure that artificial intelligence does not further deepen the linguistic and cultural asymmetries that already exist in digital technologies in general. The development of ALIA, driven by the Spain's Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2024, "based on the broad scope of our languages, spoken by 600 million people, aims to facilitate the development of advanced services and products in language technologies, offering an infrastructure marked by maximum transparency and openness".

Such initiatives are not unique to Spain. Other similar projects include BLOOM, a 176-billion-parameter multilingual model developed by more than 1,000 researchers worldwide and supporting 46 natural languages and 13 programming languages. In China, Baidu has developed ERNIE, a model with strong Mandarin capabilities, while in France the PAGNOL model has focused on improving French capabilities. These parallel efforts show a global trend towards the "linguistic democratisation" of AI.

Since the beginning of 2025, the first language models in the four co-official languages, within the ALIA project, have been available. The ALIA family of models includes ALIA-40B, a model with 40.40 billion parameters, which is currently the most advanced public multilingual foundational model in Europeand which was trained for more than 8 months on the MareNostrum 5 supercomputer, processing 6.9 trillion tokens equivalent to about 33 terabytes of text (about 17 million books!). Here all kinds of official documents and scientific repositories in Spanish are included, from congressional journals to scientific repositories or official bulletins to ensure the richness and quality of your knowledge.

Although this is a multilingual model, Spanish and co-official languages have a much higher weight than usual in these models, around 20%, as the training of the model was designed specifically for these languages, reducing the relevance of English and adapting the tokens to the needs of Spanish, Catalan, Basque and Galician.. As a result, ALIA "understands" our local expressions and cultural nuances better than a generic model trained mostly in English.

Applications of the foundational models in Spanish and co-official languages

It is still too early to judge the impact on specific sectors and applications that ALIA and other models that may be developed from this experience may have. However, they are expected to serve as a basis for improving many Artificial Intelligence applications and solutions:.

- Public administration and government: ALIA could give life to virtual assistants that attend to citizens 24 hours a day for procedures such as paying taxes, renewing ID cards, applying for grants, etc., as it is specifically trained in Spanish regulations. In fact, a pilot for the Tax Agency using ALIA, which would aim to streamline internal procedures, has already been announced.

- Education: A model such as ALIA could also be the basis for personalised virtual tutors to guide students in Spanish and co-official languages. For example, assistants who explain concepts of mathematics or history in simple language and answer questions from the students, adapting to their level since, knowing our language well, they would be able to provide important nuances in the answers and understand the typical doubts of native speakers in these languages. They could also help teachers by generating exercises or summaries of readings or assisting them in correcting students' work.

- Health: ALIA could be used to analyse medical texts and assist healthcare professionals with clinical reports, medical records, information leaflets, etc. For example, it could review patient files to extract key elements, or assist professionals in the diagnostic process. In fact, the Ministry of Health is planning a pilot application with ALIA to improve early detection of heart failure in primary care.

- Justice: In the legal field, ALIA would understand technical terms and contexts of Spanish law much better than a non-specialised model as it has been trained with legal vocabulary from official documents. An ALIA-based virtual paralegal could be able to answer basic citizen queries, such as how to initiate a given legal procedure, citing the applicable law. The administration of justice could also benefit from much more accurate machine translations of court documents between co-official languages.

Future lines

The development of foundation models in Spanish, as in other languages, is beginning to be seen outside the United States as a strategic issue that contributes to guaranteeing the technological sovereignty of countries. Of course, it will be necessary to continue training more advanced versions (models with up to 175 billion parameters are targeted, which would be comparable to the most powerful in the world), incorporating new open data, and fine-tuning applications. From the Data Directorate and the SEDIA it is intended to continue to support the growth of this family of models, to keep it at the forefront and ensure its adoption.

On the other hand, these first foundational models in Spanish and co-official languages have initially focused on written language, so the next natural frontier could be multimodality. Integrating the capacity to manage images, audio or video in Spanish together with the text would multiply its practical applications, since the interpretation of images in Spanish is one of the areas where the greatest deficiencies are detected in the large generic models.

Ethical issues will also need to be monitored to ensure that these models do not perpetuate bias and are useful for all groups, including those who speak different languages or have different levels of education. In this respect, Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is not optional, but a fundamental requirement to ensure its responsible adoption.. The National AI Supervisory Agency, the research community and civil society itself will have an important role to play here.

Content prepared by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The European Union is at the forefront of the development of safe, ethical and people-centred artificial intelligence (AI). Through a robust regulatory framework, based on human rights and fundamental values, the EU is building an AI ecosystem that simultaneously benefits citizens, businesses and public administrations. As part of its commitment to the proper development of this technology, the European Commission has proposed a set of actions to promote its excellence.

In this regard, a pioneering piece of legislation that establishes a comprehensive legal framework stands out: the AI Act. It classifies artificial intelligence models according to their level of risk and establishes specific obligations for providers regarding data and data governance. In parallel, the Coordinated Plan on AI updated in 2021 sets out a roadmap to boost investment, harmonise policies and encourage the uptake of AI across the EU.

Spain is aligned with Europe in this area and therefore has a strategy to accelerate its development and expansion.. In addition, the transposition of the AI law has recently been approved, with the preliminary draft law for an ethical, inclusive and beneficial use of artificial intelligence.

European projects transforming key sectors

In this context, the EU is funding numerous projects that use artificial intelligence technologies to solve challenges in various fields. Below, we highlight some of the most innovative ones, some of which have already been completed and some of which are underway:

Agriculture and food sustainability

Projects currently underway:

-

ANTARES: develops smart sensor technologies and big data to help farmers produce more food in a sustainable way, benefiting society, farm incomes and the environment.

Examples of other completed projects:

-

Pantheon: developed a control and data acquisition system, equivalent to industrial SCADA, for precision farming in large hazelnut orchards, increasing production, reducing chemical inputs and simplifying management.

-

Trimbot2020: researched robotics and vision technologies to create the first outdoor gardening robot, capable of navigating varied terrain and trimming rose bushes, hedges and topiary.

Industry and manufacturing

Projects currently underway:

-

SERENA: applies AI techniques to predict maintenance needs of industrial equipment, reducing costs and time, and improving the productivity of production processes..

-

SecondHands: has developed a robot capable of proactively assisting maintenance technicians by recognising human activity and anticipating their needs, increasing efficiency and productivity in industrial environments.

Examples of other completed projects:

-

QU4LITY: combined data and AI to increase manufacturing sustainability, providing a data-shared, SME-friendly, standardised and transformative zero-defect manufacturing model.

-

KYKLOS 4.0: explored how cyber-physical systems, product lifecycle management, augmented reality and AI can transform circular manufacturing through seven large-scale pilot projects.

Transport and mobility

Projects currently underway

-

VI-DAS: A project by a Spanish company working on advanced driver assistance systems and navigation aids, combining traffic understanding with consideration of the driver's physical, mental and behavioural state to improve road safety.

-

PILOTING: adapts, integrates and demonstrates robotic solutions in an integrated platform for the inspection and maintenance of refineries, bridges and tunnels.. One of its focuses is on boosting production and access to inspection data.

Examples of other completed projects:

- FABULOS: has developed and tested a local public transport system using autonomous minibuses, demonstrating its viability and promoting the introduction of robotic technologies in public infrastructure.

Social impact research

Projects currently underway:

-

HUMAINT: provides a multidisciplinary understanding of the current state and future evolution of machine intelligence and its potential impact on human behaviour, focusing on cognitive and socio-emotional capabilities.

-

AI Watch: monitors industrial, technological and research capacity, policy initiatives in Member States, AI adoption and technical developments, and their impact on the economy, society and public services.

Examples of other completed projects:

-

TECHNEQUALITY: examined the potential social consequences of the digital age, looking at how AI and robots affect work and how automation may impact various social groups differently.

Health and well-being

Projects currently underway:

-

DeepHealth: develops advanced tools for medical image processing and predictive modelling, facilitating the daily work of healthcare personnel without the need to combine multiple tools..

-

BigO: collects and analyses anonymised data on child behaviour patterns and their environment to extract evidence on local factors involved in childhood obesity.

Examples of other completed projects:

-

PRIMAGE: has created a cloud-based platform to support decision making for malignant solid tumours, offering predictive tools for diagnosis, prognosis and monitoring, using imaging biomarkers and simulation of tumour growth..

-

SelfBACK: provided personalised support to patients with low back pain through a mobile app, using sensor-collected data to tailor recommendations to each user.

-

EYE-RISK: developed tools that predict the likelihood of developing age-related eye diseases and measures to reduce this risk, including a diagnostic panel to assess genetic predisposition.

- Solve-RD: improved diagnosis of rare diseases by pooling patient data and advanced genetic methods.

The future of AI in Europe

These examples, both past and present, are very interesting use cases of the development of artificial intelligence in Europe. However, the EU's commitment to AI is also forward-looking. And it is reflected in an ambitious investment plan: the Commission plans to invest EUR 1 billion per year in AI, from the Digital Europe and Horizon Europe programmes, with the aim of attracting more than EUR 20 billion of total AI investment per year during this decade..

The development of an ethical, transparent and people-centred IA is already an EU objective that goes beyond the legal framework. With a hands-on approach, the European Union funds projects that not only drive technological innovation, but also address key societal challenges, from health to climate change, building a more sustainable, inclusive and prosperous future for all European citizens.

The increasing adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) systems in critical areas such as public administration, financial services or healthcare has brought the need for algorithmic transparency to the forefront. The complexity of AI models used to make decisions such as granting credit or making a medical diagnosis, especially when it comes to deep learning algorithms, often gives rise to what is commonly referred to as the "black box" problem, i.e. the difficulty of interpreting and understanding how and why an AI model arrives at a certain conclusion. The LLLMs or SLMs that we use so much lately are a clear example of a black box system where not even the developers themselves are able to foresee their behaviour.

In regulated sectors, such as finance or healthcare, AI-based decisions can significantly affect people's lives and therefore it is not acceptable to raise doubts about possible bias or attribution of responsibility. As a result, governments have begun to develop regulatory frameworks such as the Artificial Intelligence Regulation that require greater explainability and oversight in the use of these systems with the additional aim of generating confidence in the advances of the digital economy.

Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) is the discipline that has emerged in response to this challenge, proposing methods to make the decisions of AI models understandable. As in other areas related to artificial intelligence, such as LLLM training, open data is an important ally of explainable artificial intelligence to build audit and verification mechanisms for algorithms and their decisions.

What is explainable AI (XAI)?

Explainable AI refers to methods and tools that allow humans to understand and trust the results of machine learning models. According to the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the NIST is the only organisation in the U.S. that has a national standards body. The four key principles of Explainable Artificial Intelligence in the US are to ensure that AI systems are transparent, understandable and trusted by users:

- Explainability (Explainability): the AI must provide clear and understandable explanations of how it arrives at its decisions and recommendations.

- Meaningful (Meaningful): explanations must be meaningful and understandable to users.

- Accuracy (Accuracy): AI must generate accurate and reliable results, and the explanation of these results must accurately reflect its performance.

- Knowledge Limits (Knowledge Limits): AI must recognise when it does not have sufficient information or confidence in a decision and refrain from issuing responses in such cases.

Unlike traditional "black box" AI systems, which generate results without revealing their internal logic, XAI works on the traceability, interpretability and accountability of these decisions. For example, if a neural network rejects a loan application, XAI techniques can highlight the specific factors that influenced the decision. Thus, while a traditional model would simply return a numerical rating of the credit file, an XAI system could also tell us something like "Payment history (23%), job stability (38%) and current level of indebtedness (32%) were the determining factors in the loan denial". This transparency is vital not only for regulatory compliance, but also for building user confidence and improving AI systems themselves.

Key techniques in XAI

The Catalogue of trusted AI tools and metrics from the OECD's Artificial Intelligence Policy Observatory (OECD.AI) collects and shares tools and metrics designed to help AI actors develop trusted systems that respect human rights and are fair, transparent, explainable, robust, safe and reliable. For example, two widely adopted methodologies in XAI are Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP).

- LIME approximates complex models with simpler, interpretable versions to explain individual predictions. It is a generally useful technique for quick interpretations, but not very stable in assigning the importance of variables from one example to another.

- SHAP quantifies the exact contribution of each input to a prediction using game theory principles. This is a more precise and mathematically sound technique, but much more computationally expensive.

For example, in a medical diagnostic system, both LIME and SHAP could help us interpret that a patient's age and blood pressure were the main factors that led to a diagnosis of high risk of infarction, although SHAP would give us the exact contribution of each variable to the decision.

One of the most important challenges in XAI is to find the balance between the predictive ability of a model and its explainability. Hybrid approaches are therefore often used, integrating a posteriori explanatory methods of decision making with complex models. For example, a bank could implement a deep learning system for fraud detection, but use SHAP values to audit its decisions and ensure that no discriminatory decisions are made.

Open data in the XAI

There are at least two scenarios in which value can be generated by combining open data with explainable artificial intelligence techniques:

- The first of these is the enrichment and validation of the explanations obtained with XAI techniques. Open data makes it possible to add layers of context to many technical explanations, which is also true for the explainability of AI models. For example, if an XAI system indicates that air pollution influenced an asthma diagnosis, linking this result to open air quality datasets from patients' areas of residence would allow validation of the correctness of the result.

- Improving the performance of AI models themselves is another area where open data brings value. For example, if an XAI system identifies that the density of urban green space significantly affects cardiovascular risk diagnoses, open urban planning data could be used to improve the accuracy of the algorithm.

It would be ideal if AI model training datasets could be shared as open data, so that it would be possible to verify model training and replicate the results. What is possible, however, is the open sharing of detailed metadata on such trainings as promoted by Google's Model Cards initiative, thus facilitating post-hoc explanations of the models' decisions. In this case it is a tool more oriented towards developers than towards the end-users of the algorithms.

In Spain, in a more citizen-driven initiative, but equally aimed at fostering transparency in the use of artificial intelligence algorithms, the Open Administration of Catalonia has started to publish comprehensible factsheets for each AI algorithm applied to digital administration services. Some are already available, such as the AOC Conversational Chatbots or the Video ID for Mobile idCat.

Real examples of open data and XAI

A recent paper published in Applied Sciences by Portuguese researchers exemplifies the synergy between XAI and open data in the field of real estate price prediction in smart cities. The research highlights how the integration of open datasets covering property characteristics, urban infrastructure and transport networks, with explainable artificial intelligence techniques such as SHAP analysis, unravels the key factors influencing property values. This approach aims to support the generation of urban planning policies that respond to the evolving needs and trends of the real estate market, promoting sustainable and equitable growth of cities.

Another study by researchers at INRIA (French Institute for Research in Digital Sciences and Technologies), also on real estate data, delves into the methods and challenges associated with interpretability in machine learning based on linked open data. The article discusses both intrinsic techniques, which integrate explainability into model design, and post hoc methods that examine and explain complex systems decisions to encourage the adoption of transparent, ethical and trustworthy AI systems.

As AI continues to evolve, ethical considerations and regulatory measures play an increasingly important role in creating a more transparent and trustworthy AI ecosystem. Explainable artificial intelligence and open data are interconnected in their aim to foster transparency, trust and accountability in AI-based decision-making. While XAI provides the tools to dissect AI decision-making, open data provides the raw material not only for training, but also for testing some XAI explanations and improving model performance. As AI continues to permeate every facet of our lives, fostering this synergy will contribute to building systems that are not only smarter, but also fairer.

Content prepared by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Open source artificial intelligence (AI) is an opportunity to democratise innovation and avoid the concentration of power in the technology industry. However, their development is highly dependent on the availability of high quality datasets and the implementation of robust data governance frameworks. A recent report by Open Future and the Open Source Initiative (OSI) analyses the challenges and opportunities at this intersection, proposing solutions for equitable and accountable data governance. You can read the full report here.

In this post, we will analyse the most relevant ideas of the document, as well as the advice it offers to ensure a correct and effective data governance in artificial intelligence open source and take advantage of all its benefits.

The challenges of data governance in AI

Despite the vast amount of data available on the web, accessing and using it to train AI models poses significant ethical, legal and technical challenges. For example:

- Balancing openness and rights: In line with the Data Governance Regulation (DGA), broad access to data should be guaranteed without compromising intellectual property rights, privacy and fairness.

- Lack of transparency and openness standards: It is important that models labelled as "open" meet clear criteria for transparency in the use of data.

- Structural biases: Many datasets reflect linguistic, geographic and socio-economic biases that can perpetuate inequalities in AI systems.

- Environmental sustainability: the intensive use of resources to train AI models poses sustainability challenges that must be addressed with more efficient practices.

- Engage more stakeholders: Currently, developers and large corporations dominate the conversation on AI, leaving out affected communities and public organisations.

Having identified the challenges, the report proposes a strategy for achieving the main goal: adequate data governance in open source AI models. This approach is based on two fundamental pillars.

Towards a new paradigm of data governance

Currently, access to and management of data for training AI models is marked by increasing inequality. While some large corporations have exclusive access to vast data repositories, many open source initiatives and marginalised communities lack the resources to access quality, representative data. To address this imbalance, a new approach to data management and use in open source AI is needed. The report highlights two fundamental changes in the way data governance is conceived:

On the one hand, adopting a data commons approach which is nothing more than an access model that ensures a balance between data openness and rights protection.. To this end, it would be important to use innovative licences that allow data sharing without undue exploitation. It is also relevant to create governance structures that regulate access to and use of data. And finally, implement compensation mechanisms for communities whose data is used in artificial intelligence.

On the other hand, it is necessary to transcend the vision focused on AI developers and include more actors in data governance, such as:

- Data owners and content-generating communities.

- Public institutions that can promote openness standards.

- Civil society organisations that ensure fairness and responsible access to data.

By adopting these changes, the AI community will be able to establish a more inclusive system, in which the benefits of data access are distributed in a manner that is equitable and respectful of the rights of all stakeholders. According to the report, the implementation of these models will not only increase the amount of data available for open source AI, but will also encourage the creation of fairer and more sustainable tools for society as a whole.

Advice and strategy

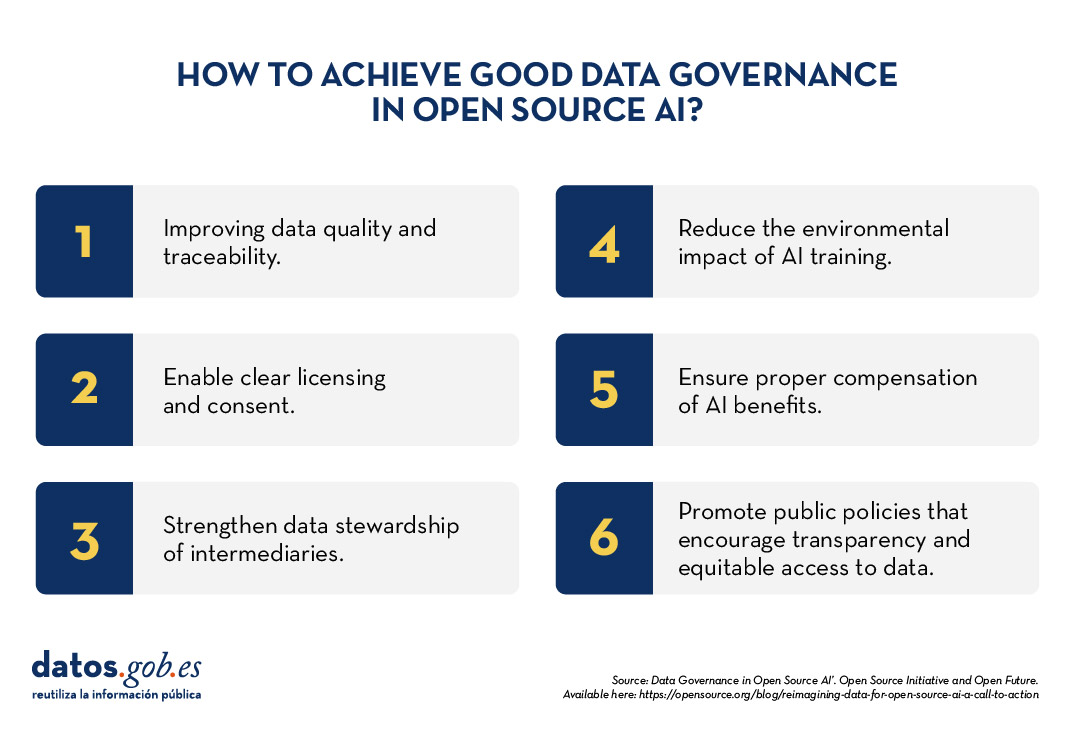

To make robust data governance effective in open source AI, the report proposes six priority areas for action:

- Data preparation and traceability: Improve the quality and documentation of data sets.

- Licensing and consent mechanisms: allow data creators to clearly define their use.

- Data stewardship: strengthen the role of intermediaries who manage data ethically.

- Environmental sustainability: Reduce the impact of AI training with efficient practices.

- Compensation and reciprocity: ensure that the benefits of AI reach those who contribute data.

- Public policy interventions: promote regulations that encourage transparency and equitable access to data.

Open source artificial intelligence can drive innovation and equity, but to achieve this requires a more inclusive and sustainable approach to data governance. Adopting common data models and broadening the ecosystem of actors will build AI systems that are fairer, more representative and accountable to the common good.

The report published by Open Future and Open Source Initiative calls for action from developers, policymakers and civil society to establish shared standards and solutions that balance open data with the protection of rights. With strong data governance, open source AI will be able to deliver on its promise to serve the public interest.

The concept of data commons emerges as a transformative approach to the management and sharing of data that serves collective purposes and as an alternative to the growing number of macrosilos of data for private use. By treating data as a shared resource, data commons facilitate collaboration, innovation and equitable access to data, emphasising the communal value of data above all other considerations. As we navigate the complexities of the digital age - currently marked by rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and the continuing debate about the challenges in data governance- the role that data commons can play is now probably more important than ever.

What are data commons?

The data commons refers to a cooperative framework where data is collected, governed and shared among all community participants through protocols that promote openness, equity, ethical use and sustainability. The data commons differ from traditional data-sharing models mainly in the priority given to collaboration and inclusion over unitary control.

Another common goal of the data commons is the creation of collective knowledge that can be used by anyone for the good of society. This makes them particularly useful in addressing today's major challenges, such as environmental challenges, multilingual interaction, mobility, humanitarian catastrophes, preservation of knowledge or new challenges in health and health care.

In addition, it is also increasingly common for these data sharing initiatives to incorporate all kinds of tools to facilitate data analysis and interpretation , thus democratising not only the ownership of and access to data, but also its use.

For all these reasons, data commons could be considered today as a criticalpublic digital infrastructure for harnessing data and promoting social welfare.

Principles of the data commons

The data commons are built on a number of simple principles that will be key to their proper governance:

- Openness and accessibility: data must be accessible to all authorised persons.

- Ethical governance: balance between inclusion and privacy.

- Sustainability: establish mechanisms for funding and resources to maintain data as a commons over time.

- Collaboration: encourage participants to contribute new data and ideas that enable their use for mutual benefit.

- Trust: relationships based on transparency and credibility between stakeholders.

In addition, if we also want to ensure that the data commons fulfil their role as public domain digital infrastructure, we must guarantee other additional minimum requirements such as: existence of permanent unique identifiers , documented metadata , easy access through application programming interfaces (APIs), portability of the data, data sharing agreements between peers and ability to perform operations on the data.

The important role of the data commons in the age of Artificial Intelligence

AI-driven innovation has exponentially increased the demand for high-quality, diverse data sets a relatively scarce commodityat a large scale that may lead to bottlenecks in the future development of the technology and, at the same time, makes data commons a very relevant enabler for a more equitable AI. By providing shared datasets governed by ethical principles, data commons help mitigate common risks such as risks, data monopolies and unequal access to the benefits of AI.

Moreover, the current concentration of AI developments also represents a challenge for the public interest. In this context, the data commons hold the key to enable a set of alternative, public and general interest-oriented AI systems and applications, which can contribute to rebalancing this current concentration of power. The aim of these models would be to demonstrate how more democratic, public interest-oriented and purposeful systems can be designed based on public AI governance principles and models.

However, the era of generative AI also presents new challenges for data commons such as, for example and perhaps most prominently, the potential risk of uncontrolled exploitation of shared datasets that could give rise to new ethical challenges due to data misuse and privacy violations.

On the other hand, the lack of transparency regarding the use of the data commons by the AI could also end up demotivating the communities that manage them, putting their continuity at risk. This is due to concerns that in the end their contribution may be benefiting mainly the large technology platforms, without any guarantee of a fairer sharing of the value and impact generated as originally intended".

For all of the above, organisations such as Open Future have been advocating for several years now for Artificial Intelligence to function as a common good, managed and developed as a digital public infrastructure for the benefit of all, avoiding the concentration of power and promoting equity and transparency in both its development and its application.

To this end, they propose a set of principles to guide the governance of the data commons in its application for AI training so as to maximise the value generated for society and minimise the possibilities of potential abuse by commercial interests:

- Share as much data as possible, while maintaining such restrictions as may be necessary to preserve individual and collective rights.

- Be fully transparent and provide all existing documentation on the data, as well as on its use, and clearly distinguish between real and synthetic data.

- Respect decisions made about the use of data by persons who have previously contributed to the creation of the data, either through the transfer of their own data or through the development of new content, including respect for any existing legal framework.

- Protect the common benefit in the use of data and a sustainable use of data in order to ensure proper governance over time, always recognising its relational and collective nature.

- Ensuring the quality of data, which is critical to preserving its value as a common good, especially given the potential risks of contamination associated with its use by AI.

- Establish trusted institutions that are responsible for data governance and facilitate participation by the entire data community, thus going a step beyond the existing models for data intermediaries.

Use cases and applications

There are currently many real-world examples that help illustrate the transformative potential of data commons:

- Health data commons : projects such as the National Institutes of Health's initiative in the United States - NIH Common Fund to analyse and share large biomedical datasets, or the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Research Data Commons , demonstrate how data commons can contribute to the acceleration of health research and innovation.

- AI training and machine learning: the evaluation of AI systems depends on rigorous and standardised test data sets. Initiatives such as OpenML or MLCommons build open, large-scale and diverse datasets, helping the wider community to deliver more accurate and secure AI systems.

- Urban and mobility data commons : cities that take advantage of shared urban data platforms improve decision-making and public services through collective data analysis, as is the case of Barcelona Dades, which in addition to a large repository of open data integrates and disseminates data and analysis on the demographic, economic, social and political evolution of the city. Other initiatives such as OpenStreetMaps itself can also contribute to providing freely accessible geographic data.

- Culture and knowledge preservation: with such relevant initiatives in this field as Mozilla's Common Voice project to preserve and revitalise the world's languages, or Wikidata, which aims to provide structured access to all data from Wikimedia projects, including the popular Wikipedia.

Challenges in the data commons

Despite their promise and potential as a transformative tool for new challenges in the digital age, the data commons also face their own challenges:

- Complexity in governance: Striking the right balance between inclusion, control and privacy can be a delicate task.

- Sustainability: Many of the existing data commons are fighting an ongoing battle to try to secure the funding and resources they need to sustain themselves and ensure their long-term survival.

- Legal and ethical issues: addressing challenges relating to intellectual property rights, data ownership and ethical use remain critical issues that have yet to be fully resolved.

- Interoperability: Ensuring compatibility between datasets and platforms is a persistent technical hurdle in almost any data sharing initiative, and the data commons were to be no exception.

The way forward

To unlock their full potential, the data commons require collective action and a determined commitment to innovation. Key actions include:

- Develop standardised governance models that strike a balance between ethical considerations and technical requirements.

- Apply the principle of reciprocity in the use of data, requiring those who benefit from it to share their results back with the community.

- Protection of sensitive data through anonymisation, preventing data from being used for mass surveillance or discrimination.

- Encourage investment in infrastructure to support scalable and sustainable data exchange.

- Promote awareness of the social benefits of data commons to encourage participation and collaboration.

Policy makers, researchers and civil society organisations should work together to create an ecosystem in which the data commons can thrive, fostering more equitable growth in the digital economy and ensuring that the data commons can benefit all.

Conclusion

The data commons can be a powerful tool for democratising access to data and fostering innovation. In this era defined by AI and digital transformation, they offer us an alternative path to equitable, sustainable and inclusive progress. Addressing its challenges and adopting a collaborative governance approach through cooperation between communities, researchers and regulators will ensure fair and responsible use of data.

This will ensure that data commons become a fundamental pillar of the digital future, including new applications of Artificial Intelligence, and could also serve as a key enabling tool for some of the key actions that are part of the recently announced European competitiveness compass, such as the new Data Union strategy and the AI Gigafactories initiative.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation. The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer a futuristic concept and has become a key tool in our daily lives. From movie or series recommendations on streaming platforms to virtual assistants like Alexa or Google Assistant on our devices, AI is everywhere. But how do you build an AI model? Despite what it might seem, the process is less intimidating if we break it down into clear and understandable steps.

Step 1: Define the problem

Before we start, we need to be very clear about what we want to solve. AI is not a magic wand: different models will work better in different applications and contexts so it is important to define the specific task we want to execute. For example, do we want to predict the sales of a product? Classify emails as spam or non-spam? Having a clear definition of the problem will help us structure the rest of the process.

In addition, we need to consider what kind of data we have and what the expectations are. This includes determining the desired level of accuracy and the constraints of available time or resources.

Step 2: Collect the data

The quality of an AI model depends directly on the quality of the data used to train it. This step consists of collecting and organising the data relevant to our problem. For example, if we want to predict sales, we will need historical data such as prices, promotions or buying patterns.

Data collection starts with identifying relevant sources, which can be internal databases, sensors, surveys... In addition to the company's own data, there is a wide ecosystem of data, both open and proprietary, that can be drawn upon to build more powerful models. For example, the Government of Spain makes available through the datos.gob.es portal multiple sets of open data published by public institutions. On the other hand, Amazon Web Services (AWS) through its AWS Data Exchange portal allows access and subscription to thousands of proprietary datasets published and maintained by different companies and organisations.

The amount of data required must also be considered here. AI models often require large volumes of information to learn effectively. It is also crucial that the data are representative and do not contain biases that could affect the results. For example, if we train a model to predict consumption patterns and only use data from a limited group of people, it is likely that the predictions will not be valid for other groups with different behaviours.

Step 3: Prepare and explore the data

Once the data have been collected, it is time to clean and normalise them. In many cases, raw data may contain problems such as errors, duplications, missing values, inconsistencies or non-standardised formats. For example, you might find empty cells in a sales dataset or dates that do not follow a consistent format. Before feeding the model with this data, it is essential to fit it to ensure that the analysis is accurate and reliable. This step not only improves the quality of the results, but also ensures that the model can correctly interpret the information.

Once the data is clean, it is essential to perform feature engineering (feature engineering), a creative process that can make the difference between a basic model and an excellent one. This phase consists of creating new variables that better capture the nature of the problem we want to solve. For example, if we are analysing onlinesales, in addition to using the direct price of the product, we could create new characteristics such as the price/category_average ratio, the days since the last promotion, or variables that capture the seasonality of sales. Experience shows that well-designed features are often more important for the success of the model than the choice of the algorithm itself.

In this phase, we will also carry out a first exploratory analysis of the data, seeking to familiarise ourselves with the data and detect possible patterns, trends or irregularities that may influence the model. Further details on how to conduct an exploratory data analysis can be found in this guide .

Another typical activity at this stage is to divide the data into training, validation and test sets. For example, if we have 10,000 records, we could use 70% for training, 20% for validation and 10% for testing. This allows the model to learn without overfitting to a specific data set.

To ensure that our evaluation is robust, especially when working with limited datasets, it is advisable to implement cross-validationtechniques. This methodology divides the data into multiple subsets and performs several iterations of training and validation. For example, in a 5-fold cross-validation, we split the data into 5 parts and train 5 times, each time using a different part as the validation set. This gives us a more reliable estimate of the real performance of the model and helps us to detect problems of over-fitting or variability in the results.

Step 4: Select a model

There are multiple types of AI models, and the choice depends on the problem we want to solve. Common examples are regression, decision tree models, clustering models, time series models or neural networks. In general, there are supervised models, unsupervised models and reinforcement learning models. More detail can be found in this post on how machines learn.

When selecting a model, it is important to consider factors such as the nature of the data, the complexity of the problem and the ultimate goal. For example, a simple model such as linear regression may be sufficient for simple, well-structured problems, while neural networks or advanced models might be needed for tasks such as image recognition or natural language processing. In addition, the balance between accuracy, training time and computational resources must also be considered. A more accurate model generally requires more complex configurations, such as more data, deeper neural networks or optimised parameters. Increasing the complexity of the model or working with large datasets can significantly lengthen the time needed to train the model. This can be a problem in environments where decisions must be made quickly or resources are limited and require specialised hardware, such as GPUs or TPUs, and larger amounts of memory and storage.

Today, many open source libraries facilitate the implementation of these models, such as TensorFlow, PyTorch or scikit-learn.

Step 5: Train the model

Training is at the heart of the process. During this stage, we feed the model with training data so that it learns to perform its task. This is achieved by adjusting the parameters of the model to minimise the error between its predictions and the actual results.

Here it is key to constantly evaluate the performance of the model with the validation set and make adjustments if necessary. For example, in a neural network-type model we could test different hyperparameter settings such as learning rate, number of hidden layers and neurons, batch size, number of epochs, or activation function, among others.

Step 6: Evaluate the model

Once trained, it is time to test the model using the test data set we set aside during the training phase. This step is crucial to measure how it performs on data that is new to the model and ensures that it is not "overtrained", i.e. that it not only performs well on training data, but that it is able to apply learning on new data that may be generated on a day-to-day basis.

When evaluating a model, in addition to accuracy, it is also common to consider:

- Confidence in predictions: assess how confident the predictions made are.

- Response speed: time taken by the model to process and generate a prediction.

- Resource efficiency: measure how much memory and computational usage the model requires.

- Adaptability: how well the model can be adjusted to new data or conditions without complete retraining.

Step 7: Deploy and maintain the model

When the model meets our expectations, it is ready to be deployed in a real environment. This could involve integrating the model into an application, automating tasks or generating reports.

However, the work does not end here. The AI needs continuous maintenance to adapt to changes in data or real-world conditions. For example, if buying patterns change due to a new trend, the model will need to be updated.

Building AI models is not an exact science, it is the result of a structured process that combines logic, creativity and perseverance. This is because multiple factors are involved, such as data quality, model design choices and human decisions during optimisation. Although clear methodologies and advanced tools exist, model building requires experimentation, fine-tuning and often an iterative approach to obtain satisfactory results. While each step requires attention to detail, the tools and technologies available today make this challenge accessible to anyone interested in exploring the world of AI.

ANNEX I - Definitions Types of models

-

Regression: supervised techniques that model the relationship between a dependent variable (outcome) and one or more independent variables (predictors). Regression is used to predict continuous values, such as future sales or temperatures, and may include approaches such as linear, logistic or polynomial regression, depending on the complexity of the problem and the relationship between the variables.

-

Decision tree models: supervised methods that represent decisions and their possible consequences in the form of a tree. At each node, a decision is made based on a characteristic of the data, dividing the set into smaller subsets. These models are intuitive and useful for classification and prediction, as they generate clear rules that explain the reasoning behind each decision.

-

Clustering models: unsupervised techniques that group data into subsets called clusters, based on similarities or proximity between the data. For example, customers with similar buying habits can be grouped together to personalise marketing strategies. Models such as k-means or DBSCAN allow useful patterns to be identified without the need for labelled data.

-

Time series models: designed to work with chronologically ordered data, these models analyse temporal patterns and make predictions based on history. They are used in cases such as demand forecasting, financial analysis or meteorology. They incorporate trends, seasonality and relationships between past and future data.

-

Neural networks: models inspired by the workings of the human brain, where layers of artificial neurons process information and detect complex patterns. They are especially useful in tasks such as image recognition, natural language processing and gaming. Neural networks can be simple or deep learning, depending on the problem and the amount of data.

-

Supervised models: these models learn from labelled data, i.e., sets in which each input has a known outcome. The aim is for the model to generalise to predict outcomes in new data. Examples include spam and non-spam mail classification and price predictions.

-

Unsupervised models: twork with unlabelled data, looking for hidden patterns, structures or relationships within the data. They are ideal for exploratory tasks where the expected outcome is not known in advance, such as market segmentation or dimensionality reduction.

- Reinforcement learning model: in this approach, an agent learns by interacting with an environment, making decisions and receiving rewards or penalties based on performance. This type of learning is useful in problems where decisions affect a long-term goal, such as training robots, playing video games or developing investment strategies.

Content prepared by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies linked to the data economy. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

In this episode we will discuss artificial intelligence and its challenges, based on the European Regulation on Artificial Intelligence that entered into force this year. Come and find out about the challenges, opportunities and new developments in the sector from two experts in the field:

- Ricard Martínez, professor of constitutional law at the Universitat de València where he directs the Chair of Privacy and Digital Transformation Microsoft University of Valencia.

- Carmen Torrijos, computational linguist, expert in AI applied to language and professor of text mining at the Carlos III University.

Listen to the full podcast (only available in Spanish)

Summary / Transcript of the interview

1. It is a fact that artificial intelligence is constantly evolving. To get into the subject, I would like to hear about the latest developments in AI?

Carmen Torrijos: Many new applications are emerging. For example, this past weekend there has been a lot of buzz about an AI for image generation in X (Twitter), I don't know if you've been following it, called Grok. It has had quite an impact, not because it brings anything new, as image generation is something we have been doing since December 2023. But this is an AI that has less censorship, that is, until now we had a lot of difficulties with the generalist systems to make images that had faces of celebrities or had certain situations and it was very monitored from any tool. What Grok does is to lift all that up so that anyone can make any kind of image with any famous person or any well-known face. It is probably a passing fad. We will make images for a while and then it will pass.

And then there are also automatic podcast creation systems, such as Notebook LM. We've been watching them for a couple of months now and it's really been one of the things that has really surprised me in the last few months. Because it already seems that they are all incremental innovations: on top of what we already have, they give us something better. But this is something really new and surprising. You upload a PDF and it can generate a podcast of two people talking in a totally natural, totally realistic way about that PDF. This is something that Notebook LM, which is owned by Google, can do.

2. The European Regulation on Artificial Intelligence is the world's first legal regulation on AI, with what objectives is this document, which is already a reference framework at international level, being published?

Ricard Martínez: The regulation arises from something that is implicit in what Carmen has told us. All this that Carmen tells is because we have opened ourselves up to the same unbridled race that we experienced with the emergence of social media. Because when this happens, it's not innocent, it's not that companies are being generous, it's that companies are competing for our data. They gamify us, they encourage us to play, they encourage us to provide them with information, so they open up. They do not open up because they are generous, they do not open up because they want to work for the common good or for humanity. They open up because we are doing their work for them. What does the EU want to stop? What we learned from social media. The European Union has two main approaches, which I will try to explain very succinctly. The first approach is a systemic risk approach. The European Union has said: "I will not tolerate artificial intelligence tools that may endanger the democratic system, i.e. the rule of law and the way I operate, or that may seriously infringe fundamental rights". That is a red line.

The second approach is a product-oriented approach. An AI is a product. When you make a car, you follow rules that manage how you produce that car, and that car comes to market when it is safe, when it has all the specifications. This is the second major focus of the Regulation. The regulation says that you can be developing a technology because you are doing research and I almost let you do whatever you want. Now, if this technology is to come to market, you will catalogue the risk. If the risk is low or slight, you are going to be able to do a lot of things and, practically speaking, with transparency and codes of conduct, I will give you a pass. But if it's a high risk, you're going to have to follow a standardised design process, and you're going to need a notified body to verify that technology, make sure that in your documentation you've met what you have to meet, and then they'll give you a CE mark. And that's not the end of it, because there will be post-trade surveillance. So, throughout the life cycle of the product, you need to ensure that this works well and that it conforms to the standard.

On the other hand, a tight control is established with regard to big data models, not only LLM, but also image or other types of information, where it is believed that they may pose systemic risks.

In that case, there is a very direct control by the Commission. So, in essence, what they are saying is: "respect rights, guarantee democracy, produce technology in an orderly manner according to certain specifications".

Carmen Torrijos: Yes, in terms of objectives it is clear. I have taken up Ricard's last point about producing technology in accordance with this Regulation. We have this mantra that the US does things, Europe regulates things and China copies things. I don't like to generalise like that. But it is true that Europe is a pioneer in terms of legislation and we would be much stronger if we could produce technology in line with the regulatory standards we are setting. Today we still can't, maybe it's a question of giving ourselves time, but I think that is the key to technological sovereignty in Europe.

3. In order to produce such technology, AI systems need data to train their models. What criteria should the data meet in order to train an AI system correctly? Could open data sets be a source? In what way?

Carmen Torrijos: The data we feed AI with is the point of greatest conflict. Can we train with any dataset even if it is available? We are not talking about open data, but about available data.

Open data is, for example, the basis of all language models, and everyone knows this, which is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is an ideal example for training, because it is open, it is optimised for computational use, it is downloadable, it is very easy to use, there is a lot of language, for example, for training language models, and there is a lot of knowledge of the world. This makes it the ideal dataset for training an AI model. And Wikipedia is in the open, it is available, it belongs to everyone and it is for everyone, you can use it.

But can all the datasets available on the Internet be used to train AI systems? That is a bit of a doubt. Because the fact that something is published on the Internet does not mean that it is public, for public use, although you can take it and train a system and start generating profit from that system. It had a copyright, authorship and intellectual property. That I think is the most serious conflict we have right now in generative AI because it uses content to inspire and create. And there, little by little, Europe is taking small steps. For example, the Ministry of Culture has launched an initiative to start looking at how we can create content, licensed datasets, to train AI in a way that is legal, ethical and respectful of authors' intellectual property rights.

All this is generating a lot of friction. Because if we go on like this, we will turn against many illustrators, translators, writers, etc. (all creators who work with content), because they will not want this technology to be developed at the expense of their content. Somehow you have to find a balance in regulation and innovation to make both happen. From the large technological systems that are being developed, especially in the United States, there is a repeated idea that only with licensed content, with legal datasets that are free of intellectual property, or that the necessary returns have been paid for their intellectual property, it is not possible to reach the level of quality of AIs that we have now. That is, only with legal datasets alone we would not have ChatGPT at the level ChatGPT is at now.

This is not set in stone and does not have to be the case. We have to continue researching, that is, we have to continue to see how we can achieve a technology of that level, but one that complies with the regulation. Because what they have done in the United States, what GPT-4 has done, the great models of language, the great models of image generation, is to show us the way. This is as far as we can go. But you have done so by taking content that is not yours, that it was not permissible to take. We have to get back to that level of quality, back to that level of performance of the models, respecting the intellectual property of the content. And that is a role that I believe is primarily Europe's responsibility.

4. Another issue of public concern with regard to the rapid development of AI is the processing of personal data. How should they be protected and what conditions does the European regulation set for this?

Ricard Martínez: There is a set of conducts that have been prohibited essentially to guarantee the fundamental rights of individuals. But it is not the only measure. I attach a great deal of importance to an article in the regulation that we are probably not going to give much thought to, but for me it is key. There is an article, the fourth one, entitled AI Literacy, which says that any subject that is intervening in the value chain must have been adequately trained. You have to know what this is about, you have to know what the state of the art is, you have to know what the implications are of the technology you are going to develop or deploy. I attach great value to it because it means incorporating throughout the value chain (developer, marketer, importer, company deploying a model for use, etc.) a set of values that entail what is called accountability, proactive responsibility, by default. This can be translated into a very simple element, which has been talked about for two thousand years in the world of law, which is 'do no harm', the principle of non-maleficence.

With something as simple as that, "do no harm to others, act in good faith and guarantee your rights", there should be no perverse effects or harmful effects, which does not mean that it cannot happen. And this is precisely what the Regulation says in particular when it refers to high-risk systems, but it is applicable to all systems. The Regulation tells you that you have to ensure compliance processes and safeguards throughout the life cycle of the system. That is why it is so important to have robustness, resilience and contingency plans that allow you to revert, shut down, switch to human control, change the usage model when an incident occurs.

Therefore, the whole ecosystem is geared towards this objective of no harm, no rights, no harm. And there is an element that no longer depends on us, it depends on public policy. AI will not only infringe on rights, it will change the way we understand the world. If there are no public policies in the education sector that ensure that our children develop computational thinking skills and are able to have a relationship with a machine-interface, their access to the labour market will be significantly affected. Similarly, if we do not ensure the continuous training of active workers and also the public policies of those sectors that are doomed to disappear.

Carmen Torrijos: I find Ricard's approach of to train is to protect very interesting. Train people, inform people, get people trained in AI, not only people in the value chain, but everybody. The more you train and empower, the more you are protecting people.

When the law came out, there was some disappointment in AI environments and especially in creative environments. Because we were in the midst of the generative AI boom and generative AI was hardly being regulated, but other things were being regulated that we took for granted would not happen in Europe, but that have to be regulated so that they cannot happen. For example, biometric surveillance: Amazon can't read your face to decide whether you are sadder that day and sell you more stuff or get more advertising or a particular advertisement. I say Amazon, but it can be any platform. This, for example, will not be possible in Europe because it is forbidden by law, it is an unacceptable use: biometric surveillance.

Another example is social scoring, the social scoring that we see happening in China, where citizens are given points and access to public services based on these points. That is not going to be possible either. And this part of the law must also be considered, because we take it for granted that this is not going to happen to us, but when you don't regulate it, that's when it happens. China has installed 600 million TRF cameras, facial recognition technology, which recognise you with your ID card. That is not going to happen in Europe because it cannot, because it is also biometric surveillance. So you have to understand that the law perhaps seems to be slowing down on what we are now enraptured by, which is generative AI, but it has been dedicated to addressing very important points that needed to be covered in order to protect people. In order not to lose fundamental rights that we have already won.

Finally, ethics has a very uncomfortable component, which nobody wants to look at, which is that sometimes it has to be revoked. Sometimes it is necessary to remove something that is in operation, even that is providing a benefit, because it is incurring some kind of discrimination, or because it is bringing some kind of negative consequence that violates the rights of a collective, of a minority or of someone vulnerable. And that is very complicated. When we have become accustomed to having an AI operating in a certain context, which may even be a public context, to stop and say that this is discriminating against people, then this system cannot continue in production and has to be removed. This point is very complicated, it is very uncomfortable and when we talk about ethics, which we talk very easily about ethics, we must also think about how many systems we are going to have to stop and review before we can put them back into operation, however easy they make our lives or however innovative they may seem.

5. In this sense, taking into account all that the Regulation contains, some Spanish companies, for example, will have to adapt to this new framework. What should organisations already be doing to prepare? What should Spanish companies review in the light of the European regulation?

Ricard Martínez: This is very important, because there is a corporate business level of high capabilities that I am not worried about because these companies understand that we are talking about an investment. And just as they invested in a process-based model that integrated the compliance from the design for data protection. The next leap, which is to do exactly the same thing with artificial intelligence, I won't say that it is unimportant, because it is of relevant importance, but let's say that it is going down a path that has already been tried. These companies already have compliance units, they already have advisors, and they already have routines into which the artificial intelligence regulatory framework can be integrated as part of the process. In the end, what it will do is to increase risk analysis in one sense. It will surely force the design processes and also the design phases themselves to be modular, i.e., while in software design we are practically talking about going from a non-functional model to chopping up code, here there are a series of tasks of enrichment, annotation, validation of the data sets, prototyping that surely require more effort, but they are routines that can be standardised.

My experience in European projects where we have worked with clients, i.e. SMEs, who expect AI to be plug and play, what we have seen is a huge lack of capacity building. The first question you should ask yourself is not whether your company needs AI, but whether your company is ready for AI. This is an earlier and rather more relevant question. Hey, you think you can make a leap into AI, that you can contract a certain type of services, and we are realising that you don't even comply with the data protection regulation.

There is something, an entity called the Spanish Agency for Artificial Intelligence, AESIA, and there is a Ministry of Digital Transformation, and if there are no accompanying public policies, we may incur risky situations. Why? Because I have the great pleasure of training future entrepreneurs in artificial intelligence in undergraduate and postgraduate courses. When confronted with the ethical and legal framework, I won't say they want to die, but the world comes crashing down on them. Because there is no support, there is no accompaniment, there are no resources, or they cannot see them, that do not involve a round of investment that they cannot bear, or there are no guided models that help them in a way that is, I won't say easy, but at least usable.

Therefore, I believe that there is a substantial challenge in public policies, because if this combination does not happen, the only companies that will be able to compete are those that already have a critical mass, an investment capacity and an accumulated capital that allows them to comply with the standard. This situation could lead to a counterproductive outcome.