We continue with the series of posts about Chat GPT-3. The expectation raised by the conversational system more than justifies the publication of several articles about its features and applications. In this post, we take a closer look at one of the latest news published by openAI related to Chat GPT-3. In this case, we introduce its API, that is, its programming interface with which we can integrate Chat GPT-3 into our own applications.

Introduction.

In our last post about Chat GPT-3 we carried out a co-programming or assisted programming exercise in which we asked the AI to write us a simple program, in R programming language, to visualise a set of data. As we saw in the post, we used Chat GTP-3's own available interface. The interface is very minimalistic and functional, we just have to ask the AI in the text box and it answers us in the subsequent text box. As we concluded in the post, the result of the exercise was more than satisfactory. However, we also detected some points for improvement. For example, the standard interface can be a bit slow. For a long exercise, with multiple conversational interactions with the AI (a long dialogue), the interface takes quite a long time to write the answers. Several users report the same feeling and so some, like this developer, have created their own interface with the conversational assistant to improve its response speed.

But how is this possible? The reason is simple, thanks to the GPT-3 Chat API. We have talked a lot about APIs in this space in the past. Not surprisingly, APIs are the standard mechanisms in the world of digital technologies for integrating services and applications. Any app on our smartphone makes use of APIs to show us results. When we consult the weather, sports results or the public transport timetable, apps make calls to the APIs of the services to consult the information and display the results.

The GPT-3 Chat API

Like any other current service, openAI provides its users with an API with which they can invoke (call) its different services based on the trained natural language model GPT-3. To use the API, we just have to log in with our account at https://platform.openai.com/ and locate the menu (top right) View API Keys. Click on create a new secret key and we have our new access key to the service.

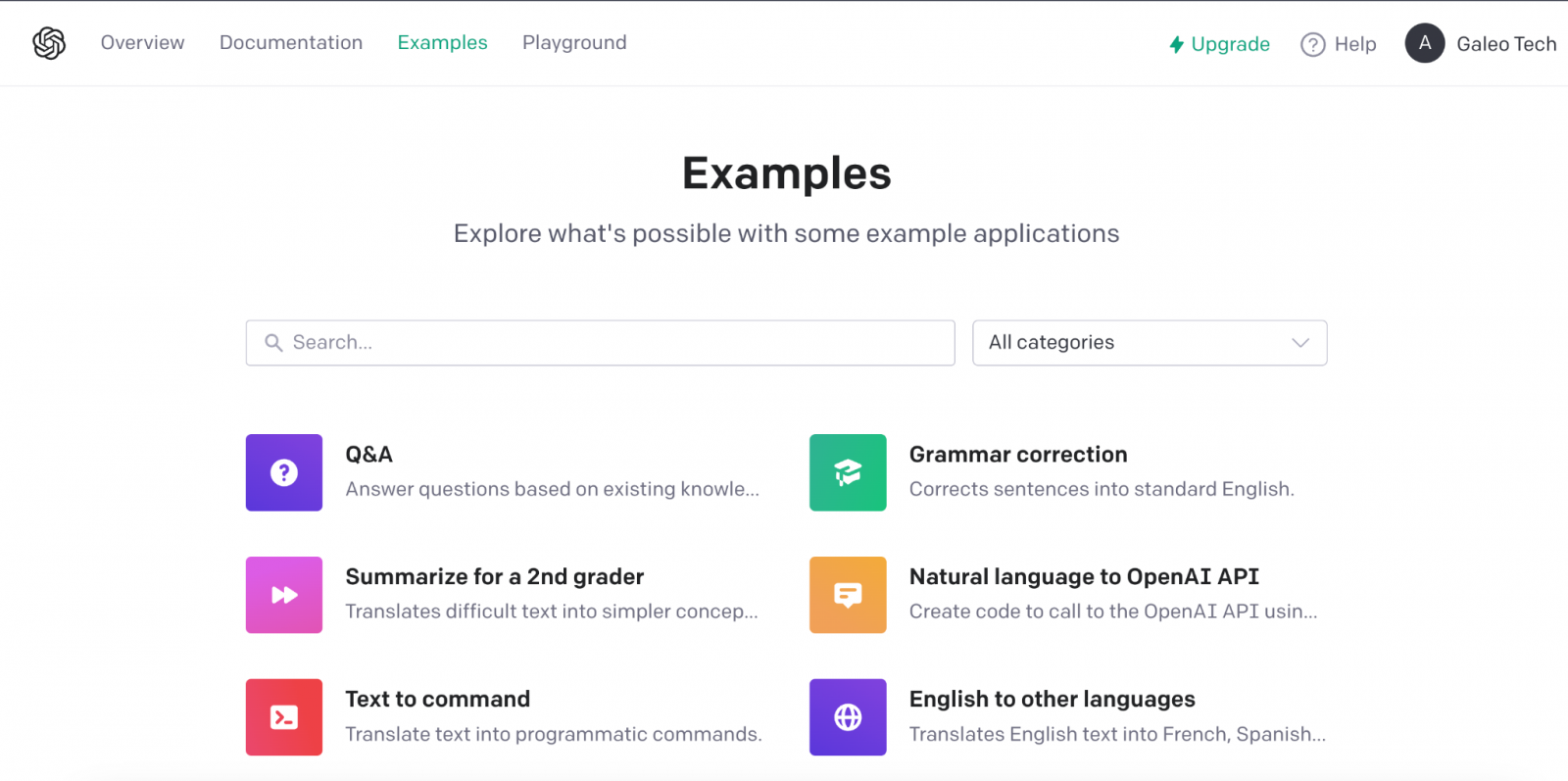

What do we do now? Well, to illustrate what we can do with this brand new key, let's look at some examples:

As we said in the introduction, we may want to try alternative interfaces to Chat GPT-3 such as https://www.typingmind.com/. When we access this website, the first thing we have to do is enter our API Key.

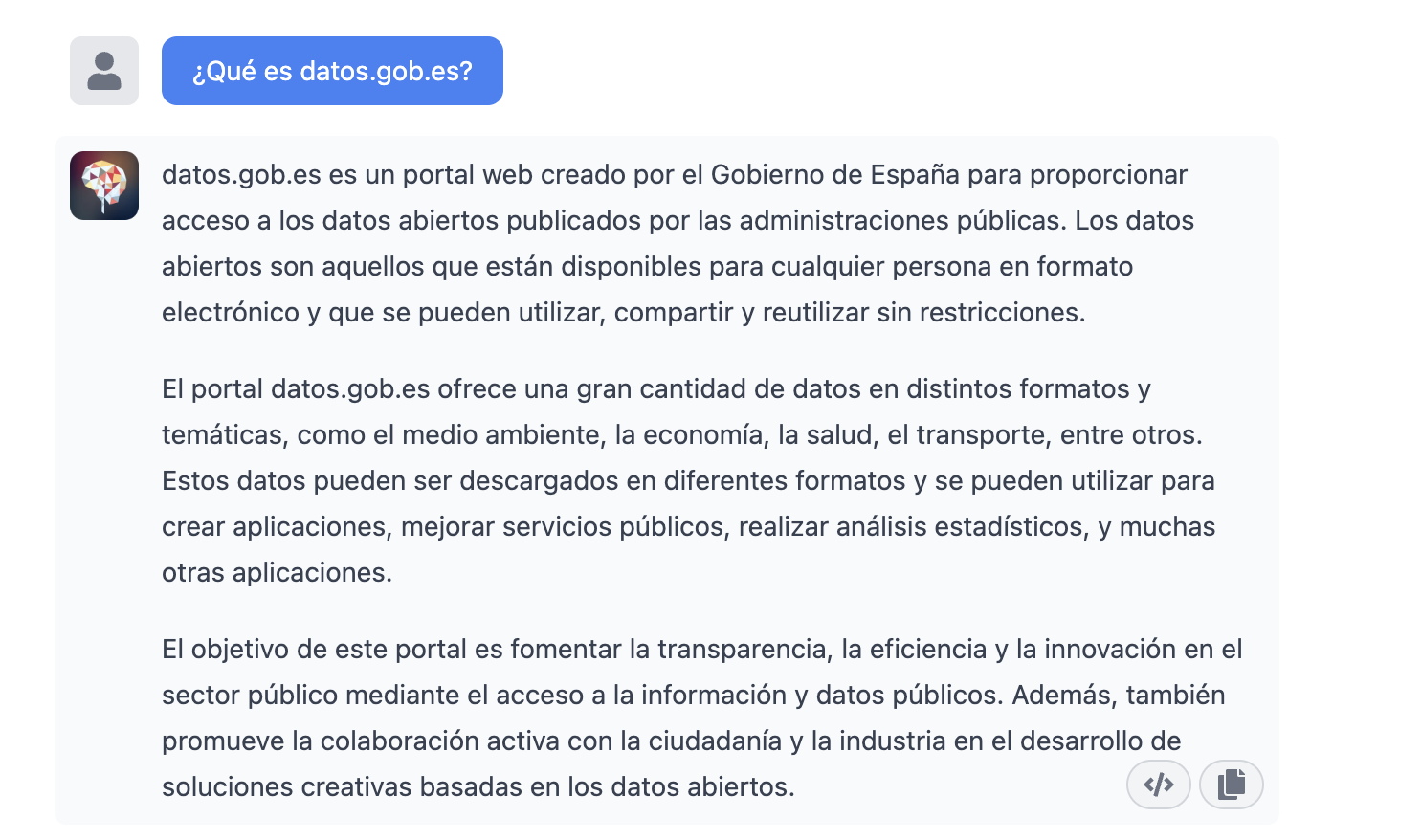

Once inside, let's do an example and see how this new interface behaves. Let's ask Chat GPT-3 What is datos.gob.es?

| Note: It is important to note that most services will not work if we do not activate a means of payment on the OpenAI website. Normally, if we have not configured a credit card, the API calls will return an error message similar to \"You exceeded your current quota, please check your plan and billing details\". |

Let's now look at another application of the GPT-3 Chat API.

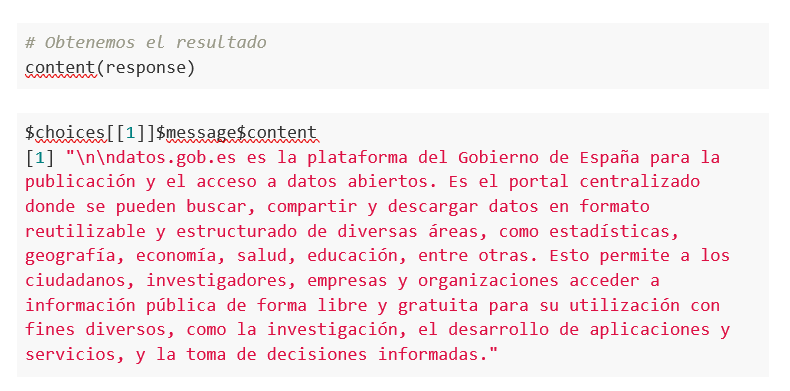

Programmatic access with R to access Chat GPT-3 programmatically (in other words, with a few lines of code in R we have access to the conversational power of the GPT-3 model). This demonstration is based on the recent post published in R Bloggers. Let's access Chat GPT-3 programmatically with the following example.

| Note: Note that the API Key has been hidden for security and privacy reasons. |

En este ejemplo, utilizamos código en R para hacer una llamada HTTPs de tipo POST y le preguntamos a Chat GPT-3 ¿Qué es datos.gob.es? Vemos que estamos utilizando el modelo gpt-3.5-turbo que, tal y como se especifica en la documentación está indicado para tareas de tipo conversacional. Toda la información sobre la API y los diferentes modelos está disponible aquí. Pero, veamos el resultado:

Not bad, right? As a curious fact we can see that a few GPT-3 Chat API calls have had the following API usage:

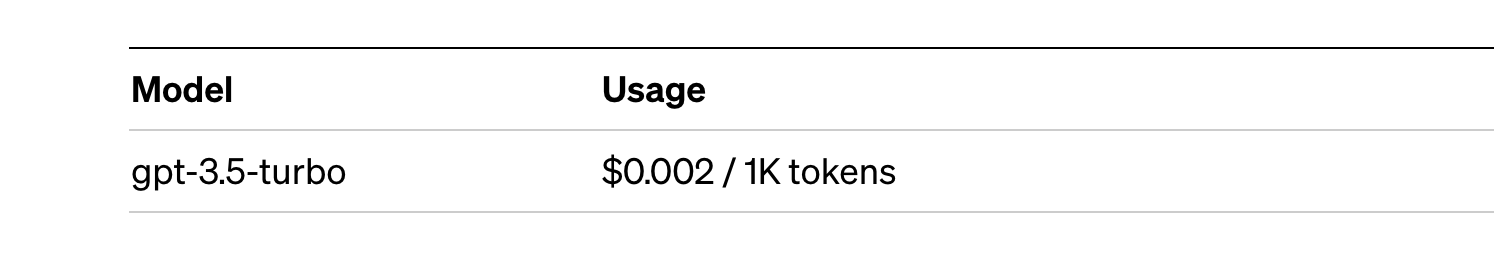

The use of the API is priced per token (something similar to words) and the public prices can be consulted here. Specifically, the model we are using has these prices:

For small tests and examples, we can afford it. In the case of enterprise applications for production environments, there is a premium model that allows you to control costs without being so dependent on usage.

Conclusion

Naturally, Chat GPT-3 enables an API to provide programmatic access to its conversational engine. This mechanism allows the integration of applications and systems (i.e. everything that is not human) opening the door to the definitive take-off of Chat GPT-3 as a business model. Thanks to this mechanism, the Bing search engine now integrates GPT-3 Chat for conversational search responses. Similarly, Microsoft Azure has just announced the availability of GPT-3 Chat as a new public cloud service. No doubt in the coming weeks we will see communications from all kinds of applications, apps and services, known and unknown, announcing their integration with GPT-3 Chat to improve conversational interfaces with their customers. See you in the next episode, maybe with GPT-4.

Behind a voice-enabled virtual assistant, a movie recommendation on a streaming platform, or the development of some COVID-19 vaccines, there are machine learning models. This branch of artificial intelligence enables systems to learn and improve their performance.

Machine learning (ML) is one of the fields driving technological progress today, and its applications are growing every day. Examples of solutions developed with machine learning include DALL-E, the set of language models in Spanish known as MarIA, and even Chat GPT-3, a generative AI tool capable of creating content of all types, such as code for programming data visualizations from the datos.gob.es catalog.

All of these solutions work thanks to large data repositories that make system learning possible. Among these, open data plays a fundamental role in the development of artificial intelligence as it can be used to train machine learning models.

Based on this premise, along with the ongoing effort of governments to open up data, there are non-governmental organizations and associations that contribute by developing applications that use machine learning techniques aimed at improving the lives of citizens. We highlight three of them:

ML Commons is driving a better machine learning system for everyone

This initiative aims to improve the positive impact of machine learning on society and accelerate innovation by offering tools such as open datasets, best practices, and algorithms. Its founding members include companies such as Google, Microsoft, DELL, Intel AI, Facebook AI, among others.

According to ML Commons, around 80% of research in the field of machine learning is based on open data. Therefore, open data is vital to accelerate innovation in this field. However, nowadays, "most public data files available are small, static, legally restricted, and not redistributable," as David Kanter, director of ML Commons, assures.

In this regard, innovative ML technologies require large datasets with licenses that allow their reuse, that can be redistributed, and that are continually improving. Therefore, ML Commons' mission is to help mitigate that gap and thus promote innovation in machine learning.

The main goal of this organization is to create a community of open data for the development of machine learning applications. Its strategy is based on three pillars:

Firstly, creating and maintaining comprehensive open datasets, including The People's Speech, with over 30,000 hours of speech in English to train natural language processing (NLP) models, Multilingual Spoken Words, with over 23 million expressions in 50 different languages, or Dollar Street, with over 38,000 images of homes from around the world in various socio-economic situations. The second pillar involves promoting best practices that facilitate standardization, such as the MLCube project, which proposes standardizing the container process for ML models to facilitate shared use. Lastly, benchmarking in study groups to define benchmarks for the developer and research community.

Taking advantage of the benefits and being part of the ML Commons community is free for academic institutions and small companies (less than ten workers).

Datacommons synthesizes different sources of open data into a single portal

Datacommons aims to enhance democratic data flows within the cooperative and solidarity economy and its main objective is to offer purified, normalized, and interoperable data.

The variety of formats and information offered by public portals of open data can be a hindrance to research. The goal of Datacommons is to compile open data into an encyclopedic website that organizes all datasets through nodes. This way, users can access the source that interests them the most.

This platform, designed for educational and journalistic research purposes, functions as a reference tool for navigating through different sources of data. The team of collaborators works to keep the information up-to-date and interacts with the community through its email (support@datacommons.org) or GitHub forum.

Papers with Code: the open repository of materials to feed machine learning models

This is a portal that offers code, reports, data, methods, and evaluation tables in open and free format. All content on the website is licensed under CC-BY-SA, meaning it allows copying, distributing, displaying, and modifying the work, even for commercial purposes, by sharing the contributions made with the same original license.

Any user can contribute by providing content and even participate in the community's Slack channel, which is moderated by responsible individuals who protect the platform's defined inclusion policy.

As of today, Papers with Code hosts 7806 datasets that can be filtered by format (graph, text, image, tabular, etc.), task (object detection, queries, image classification, etc.), or language. The team maintaining Papers with Code belongs to the Meta Research Institute.

The goal of ML Commons, Data Commons, and Papers with Code is to maintain and grow open data communities that contribute to the development of innovative technologies, including artificial intelligence (machine learning, deep learning, etc.) with all the possibilities its development can offer to society.

As part of this process, the three organizations play a fundamental role: they offer standard and redistributable data repositories to train machine learning models. These are useful resources for academic exercises, promoting research, and ultimately facilitating the innovation of technologies that are increasingly present in our society.

Talking about GPT-3 these days is not the most original topic in the world, we know it. The entire technology community is publishing examples, holding events and predicting the end of the world of language and content generation as we know it today. In this post, we ask ChatGPT to help us in programming an example of data visualisation with R from an open dataset available at datos.gob.es.

Introduction

Our previous post talked about Dall-e and GPT-3's ability to generate synthetic images from a description of what we want to generate in natural language. In this new post, we have done a completely practical exercise in which we ask artificial intelligence to help us make a simple program in R that loads an open dataset and generates some graphical representations.

We have chosen an open dataset from the platform datos.gob.es. Specifically, a simple dataset of usage data from madrid.es portals. The description of the repository explains that it includes information related to users, sessions and number of page views of the following portals of the Madrid City Council: Municipal Web Portal, Sede Electrónica, Transparency Portal, Open Data Portal, Libraries and Decide Madrid.

The file can be downloaded in .csv or .xslx format and if we preview it, it looks as follows:

OK, let's start co-programming with ChatGPT!

First we access the website and log in with our username and password. You need to be registered on the openai.com website to be able to access GPT-3 capabilities, including ChatGPT.

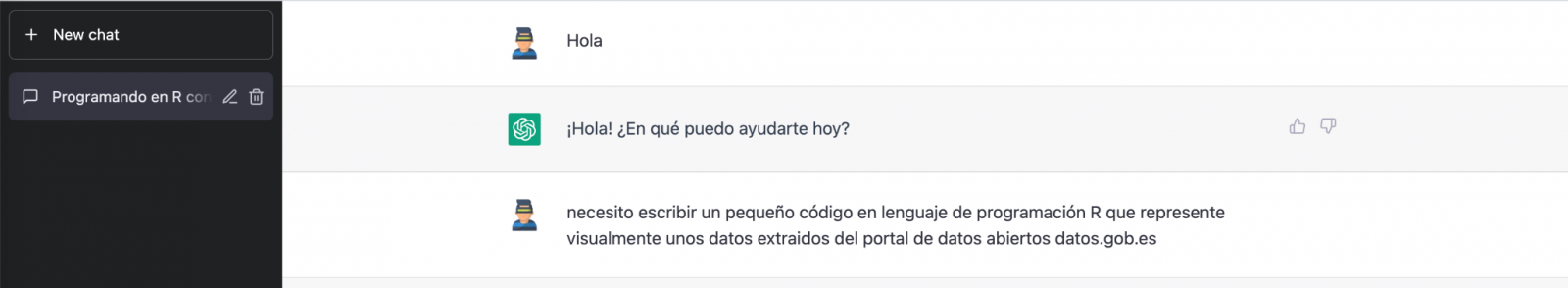

We start our conversation:

During this exercise we have tried to have a conversation in the same way as we would have with a programming partner. So the first step we do is to say ‘hello’ and mention the problem we have. When we ask the AI to help us create a small program in R that graphically represents some data, it gives us some examples and helps us with the explanation of the program:

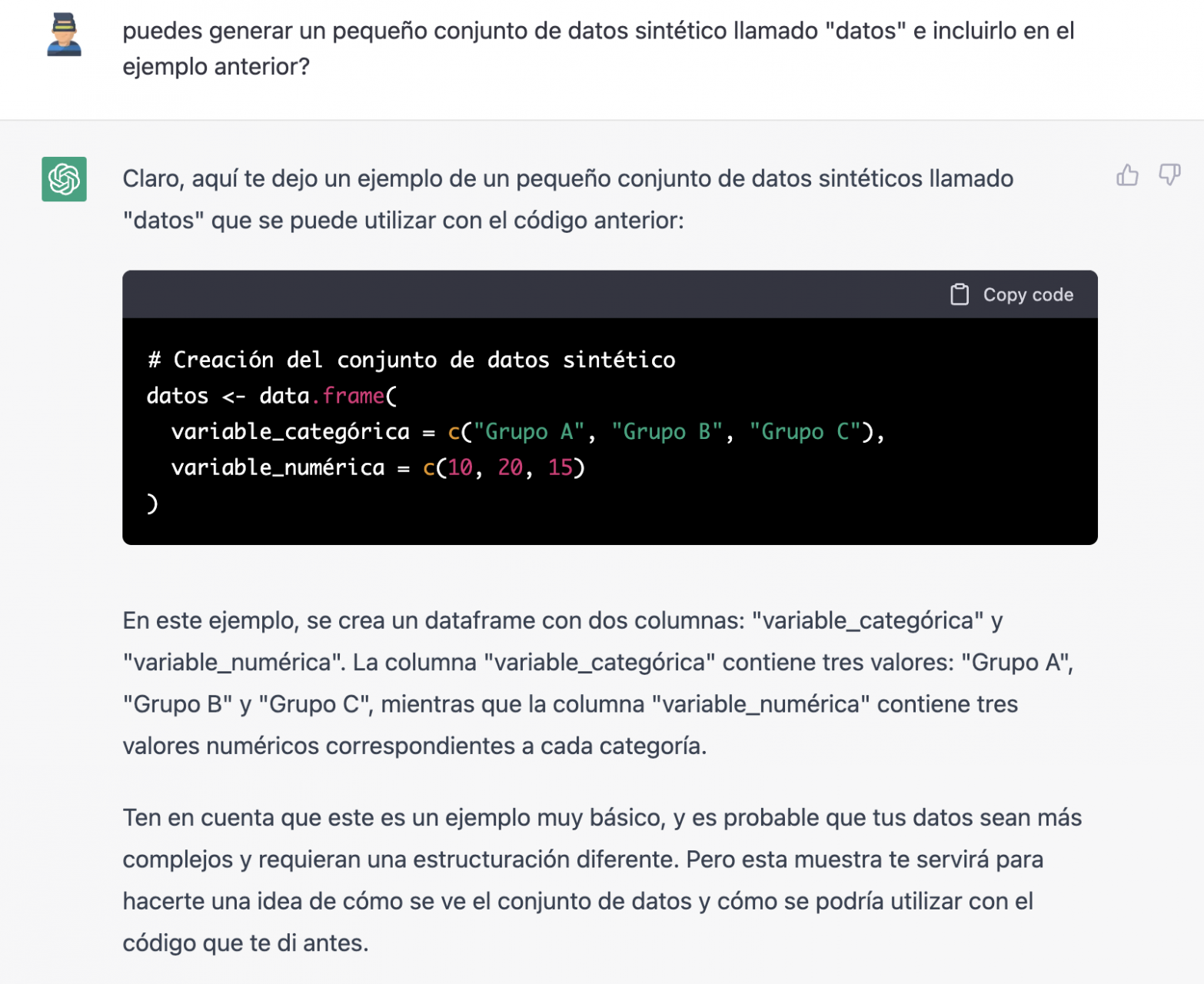

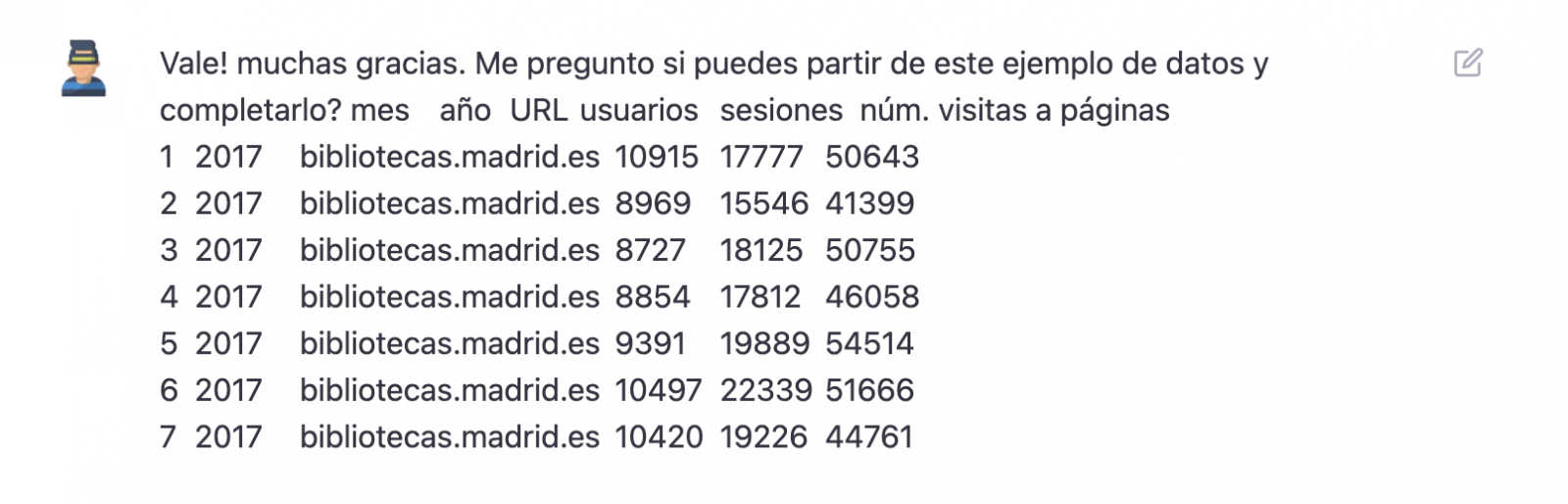

Since we have no data, we cannot do anything practical at the moment, so we ask it to help us generate some synthetic data.

As we say, we behave with the AI as we would with a person (it looks good).

Once the AI seems to easily answer our questions, we go to the next step, we are going to give it the data. And here the magic begins... We have opened the data file that we have downloaded from datos.gob.es and we have copied and pasted a sample.

| Note: ChatGPT has no internet connection and therefore cannot access external data, so all we can do is give it an example of the actual data we want to work with. |

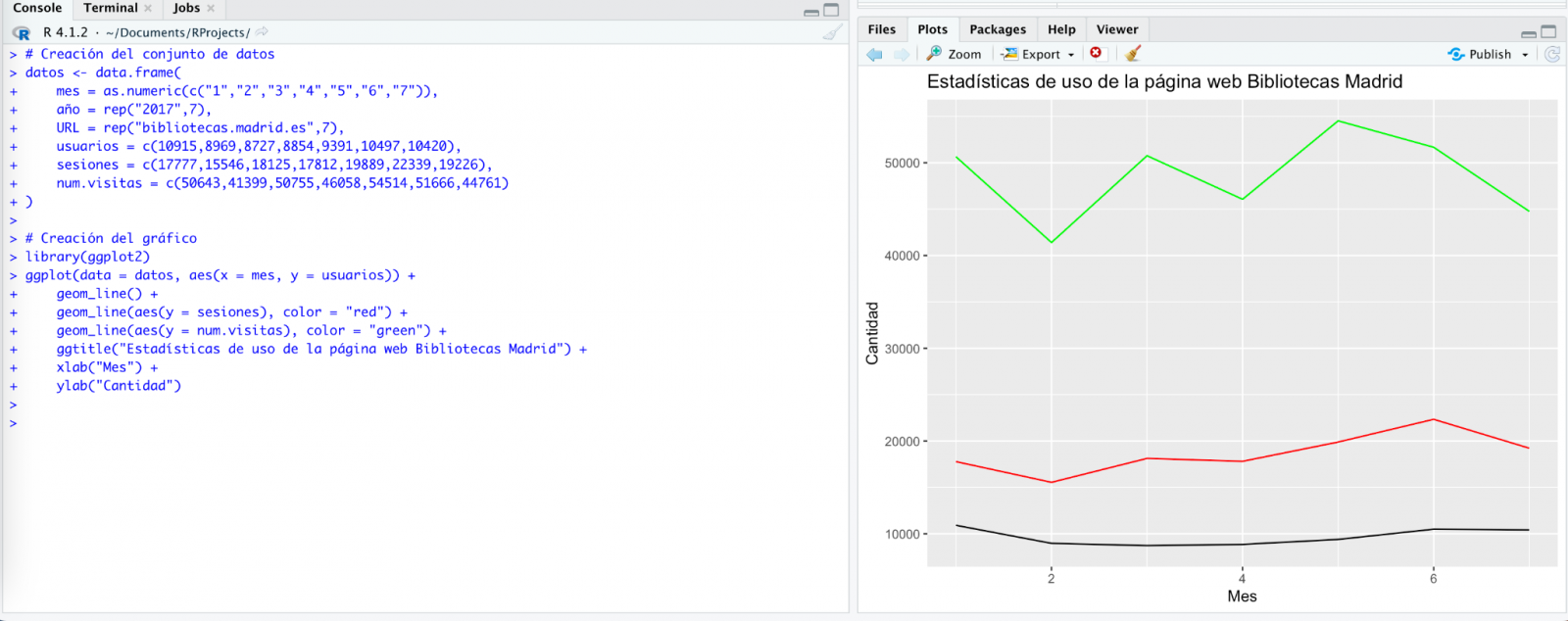

With the data copied and pasted as we have given it to it, the AI writes the code in R to load it manually into a dataframe called \"data\". It then gives us the code for ggplot2 (the most popular graphics library in R) to plot the data along with an explanation of how the code works.

Great! This is a spectacular result with a totally natural language and not at all adapted to talk to a machine. Let's see what happens next:

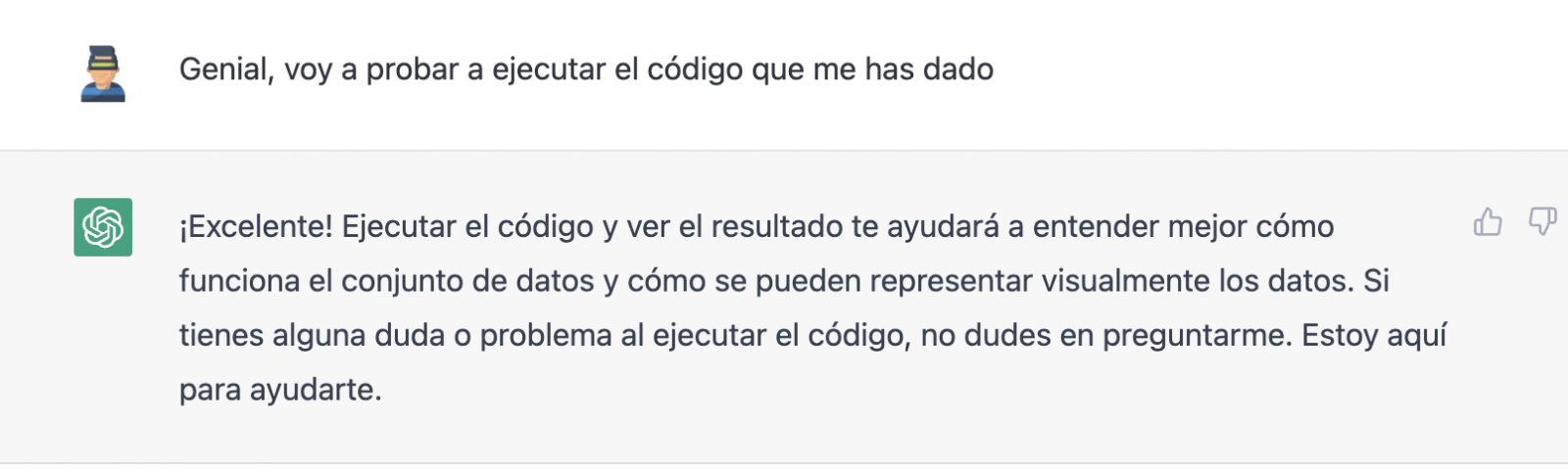

But it turns out that when we copy and paste the code into an RStudio environment it is no running.

So, we tell to it what's going on and ask it to help us to solve it.

We tried again and, in this case, it works!

However, the result is a bit clumsy. So, we tell it.

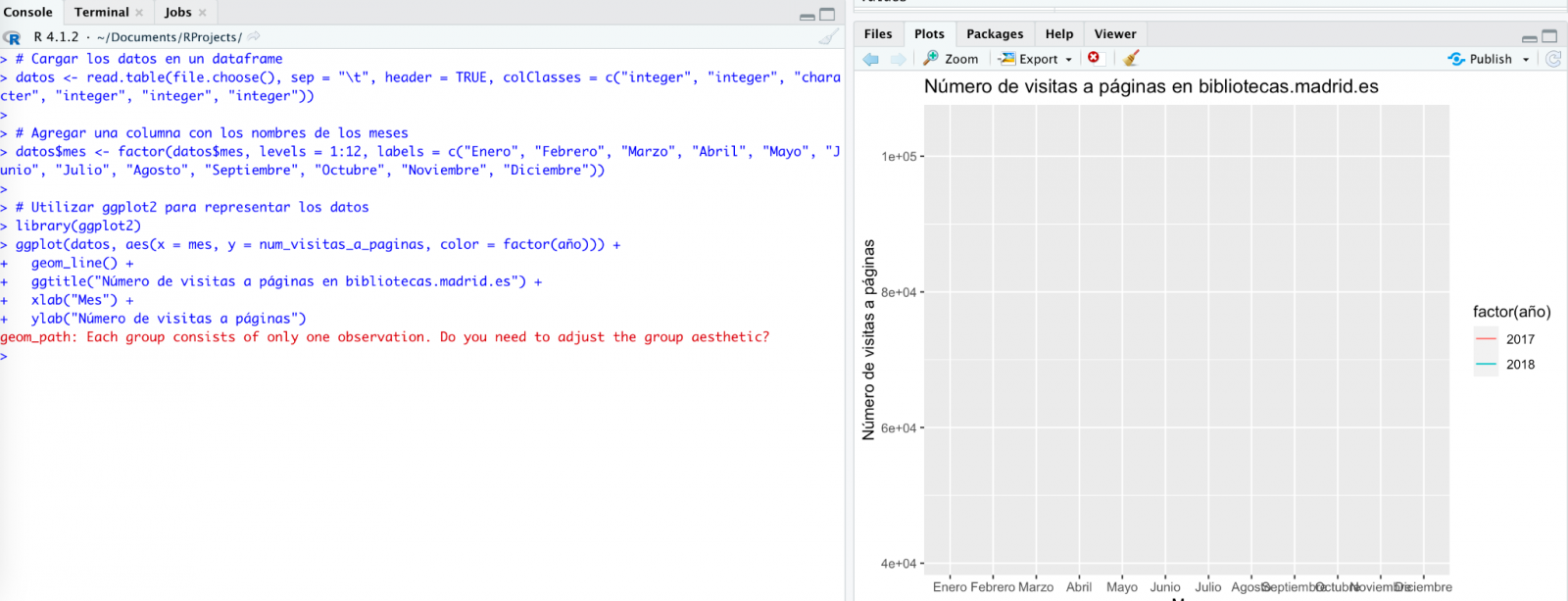

From here (and after several attempts to copy and paste more and more rows of data) the AI changes the approach slightly and provides me with instructions and code to load my own data file from my computer instead of manually entering the data into the code.

We take its opinion into account and copy a couple of years of data into a text file on our computer. Watch what happens next:

We try again:

As you can see, it works, but the result is not quite right.

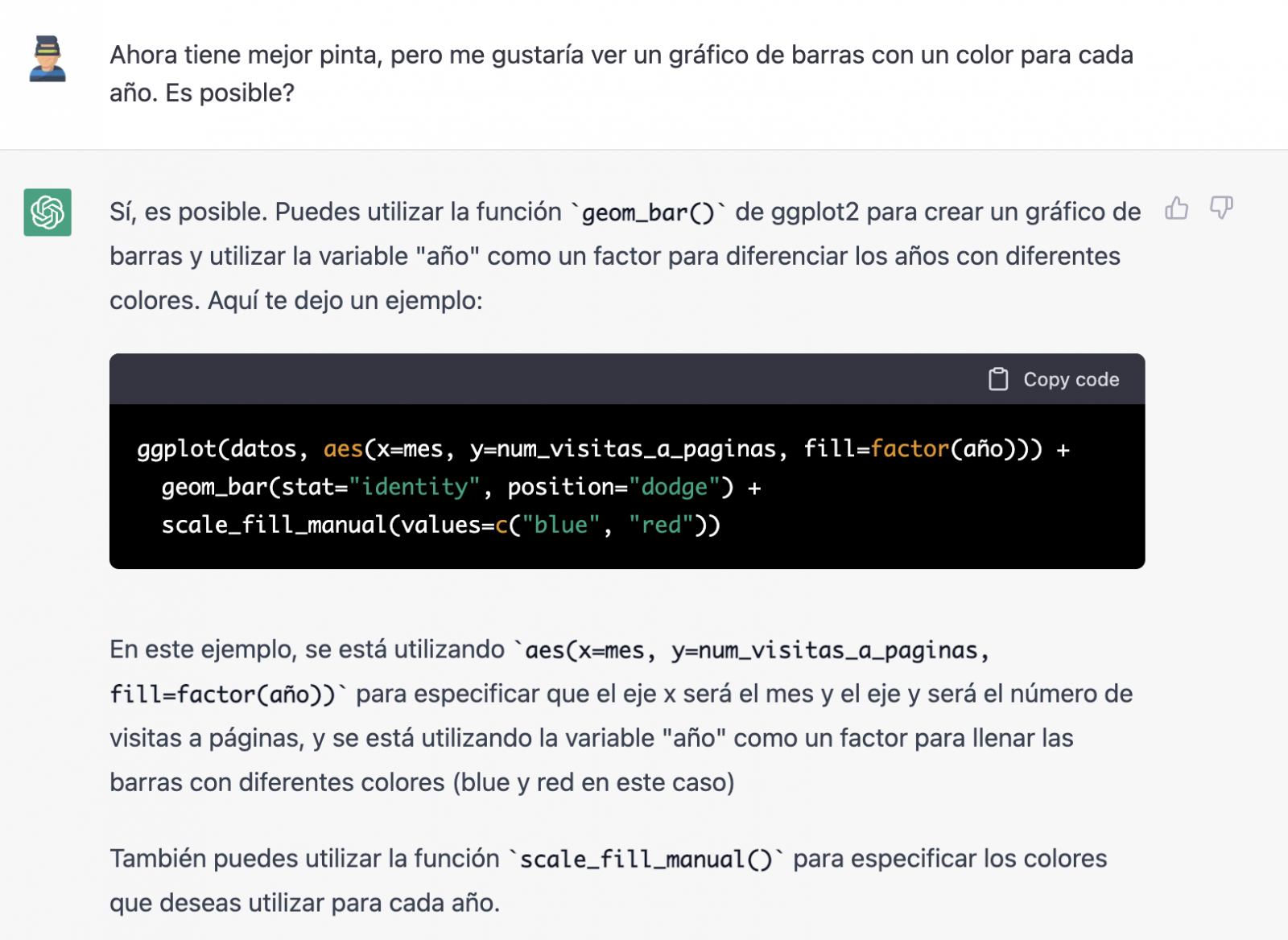

And let's see what happens.

Finally, it looks like it has understood us! That is, we have a bar chart with the visits to the website per month, for the years 2017 (blue) and 2018 (red). However, I am not convinced by the format of the axis title and the numbering of the axis itself.

Let's look at the result now.

It looks much better, doesn't it? But what if we give it one more twist?

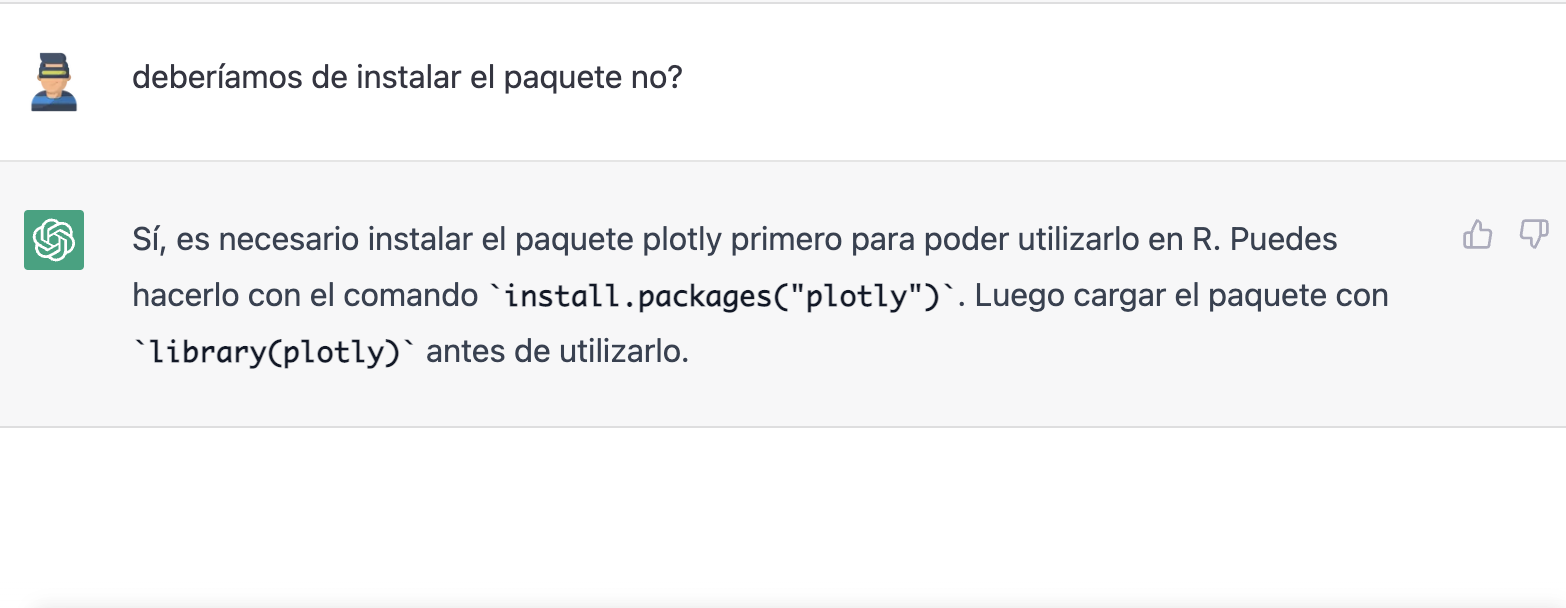

However, it forgot to tell us that we must install the plotly package or library in R. So, we remind it.

Let's have a look at the result:

As you can see, we have now the interactive chart controls, so that we can select a particular year from the legend, zoom in and out, and so on.

Conclusion

You may be one of those sceptics, conservatives or cautious people who think that the capabilities demonstrated by GPT-3 so far (ChatGPT, Dall-E2, etc) are still very infantile and impractical in real life. All considerations in this respect are legitimate and, many of them, probably well-founded.

However, some of us have spent a good part of our lives writing programs, looking for documentation and code examples that we could adapt or take inspiration from; debugging bugs, etc. For all of us (programmers, analysts, scientists, etc.) to be able to experience this level of interlocution with an artificial intelligence in beta mode, made freely available to the public and being able to demonstrate this capacity for assistance in co-programming, is undoubtedly a qualitative and quantitative leap in the discipline of programming.

We don't know what is going to happen, but we are probably on the verge of a major paradigm shift in computer science, to the point that perhaps the way we program has changed forever and we haven't even realised it yet.

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, Digital Transformation expert.

The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Generative artificial intelligence refers to machine’s ability to generate original and creative content, such as images, text or music, from a set of input data. As far as text generation is concerned, these models have been accessible, in an experimental format, for some time, but began to generate interest in mid-2020 when Open AI, an organisation dedicated to research in the field of artificial intelligence, published access to its GPT-3 language model via an API.

The GPT-3's architecture is composed of 175 billion parameters, comparing to its predecessor GPT-2 was 1.5 billion parameters, i.e. more than 100 times more. Therefore, GPT-3 represents a huge change in scale as it was also trained with a much larger corpus of data and a much larger token size, which allowed it to acquire a deeper and more complex understanding of the human language.

Although it was in 2022 when OpenAI announced the launch of chatGPT, which provides a conversational interface to a language model based on an improved version of GPT-3, it has only been in the last two months that the chat has attracted massive public attention, thanks to extensive media coverage that tries to respond to the emerging general interest.

In fact, ChatGPT is not only able to generate text from a set of characters (prompt) like GPT-3, but also it is able to respond to natural language questions in several languages including English, Spanish, French, German, Italian or Portuguese. This specific updated issue in the access interface from an API to a chatbot that has made the AI accessible to any type of user.

Maybe for this reason, more than a million people registered to use it in just five days, which has led to the multiplication of examples in which chatGPT produces software code, university-level essays, poems and even jokes. Not to mention the fact that it has been able to ace an history SAT or pass the final MBA exam at the prestigious Wharton School.

All of this has put generative AI at the centre of a new wave of technological innovation that promises to revolutionise the way we relate to the internet and the web through AI-powered searches or browsers capable of summarising the results of these searches.

Just a few days ago, we heard the news that Microsoft is working on the implementation of a conversational system within its own search engine, which has been developed based on the well-known Open AI language model and whose news has put Google in check.

As a result of this new reality in which AI is here to stay, the technological giants have gone a step further in the battle to make the most of the benefits it brings. Along these lines, Microsoft has presented a new strategy aimed at optimising the way in which we interact with the internet, introducing AI to improve the results offered by browser search engines, applications, social networks and, in short, the entire web ecosystem.

However, although the path in the development of new and future services offered by Open AI's remains to be seen, advances such as the mentioned above, offer a small hint of the browser war that is coming and that will probably change the way we create and find content on the web in the short term.

The open data

GPT-3, like other models that have been generated with the techniques described in the original GTP-3 scientific publication, is a pre-trained language model, which means that it has been trained with a large dataset, in total about 45 terabytes of text data. According to the paper, the training dataset was composed of 60% of data obtained directly from the internet containing millions of documents of all kinds, 22% from the WebText2 corpus built from Reddit, and the rest from a combination of books (16%) and Wikipedia (3%).

However, it is not known exactly how much open datasets GPT-3 uses, as OpenAI does not provide more specific details about the dataset used to train the model. What we can ask chatGPT itself are some questions that can help us draw interesting conclusions about its use of open data.

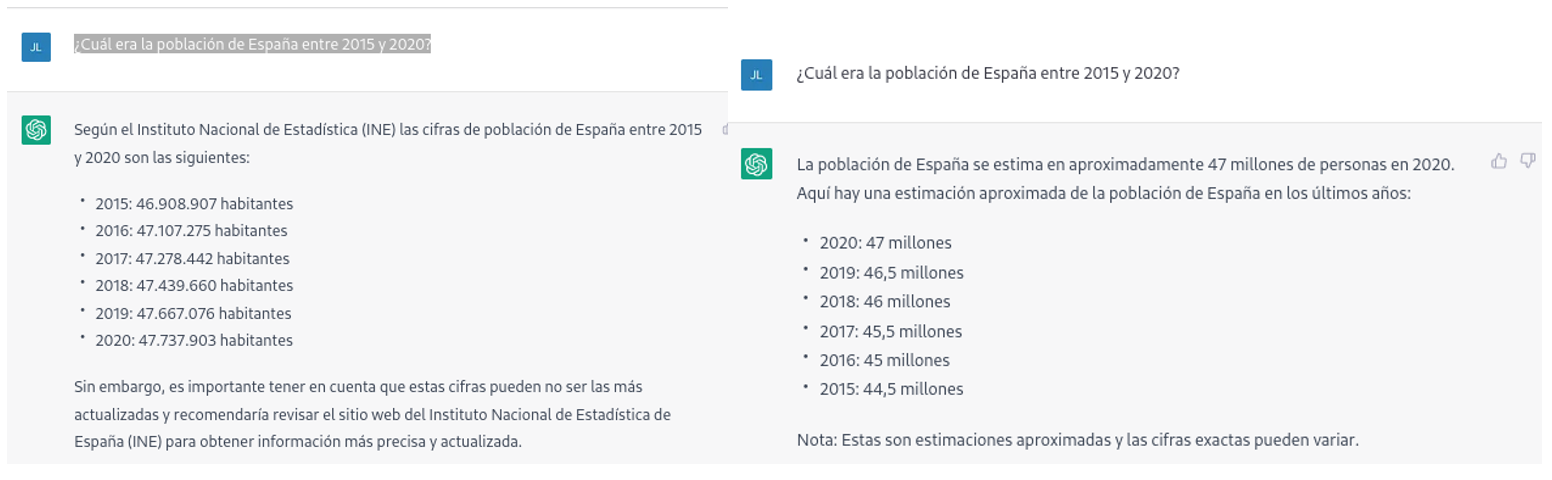

For example, if we ask chatGPT what was the population of Spain between 2015 and 2020 (we cannot ask for more recent data), we get an answer like this:

As we can see in the image above, although the question is the same, the answer may vary in both the wording and the information it contains. The variations can be even greater if we ask the question on different days or in different threads:

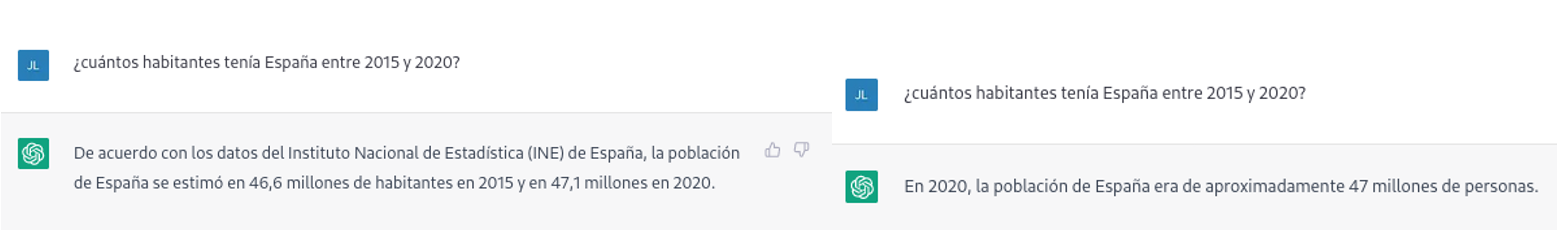

Small variations in the wording of the text, generating the question at different times in the conversation thread (remember that it saves the context) or in different threads or on different days may lead to slightly different results. Moreover, the answer is not completely accurate, as the tool itself warns us if we compare it with the INE's own series on the resident population in Spain, where it recommends us to consult. The data that we would ideally have expected in the response could be obtained in an open INE dataset:

Such responses suggest that open data has not been used as an authoritative source for answering factual questions, or at least that the model is not yet fully refined on this matter. Doing some basic tests with questions about other countries we have observed similar errors, so this does not seem to be a problem only with questions referring to Spain.

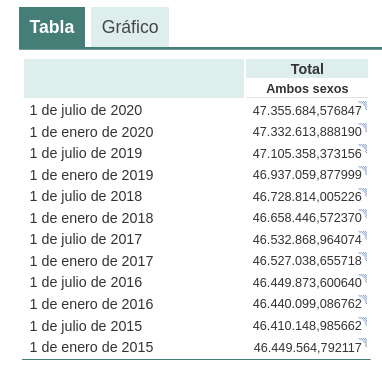

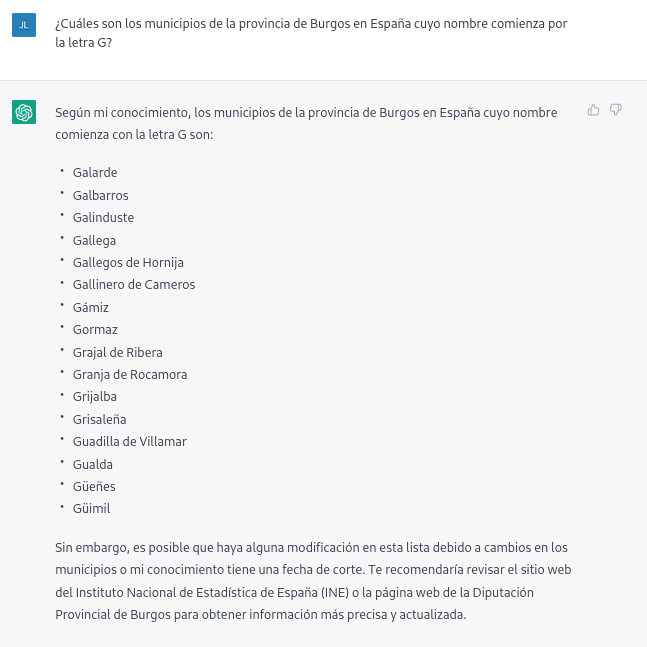

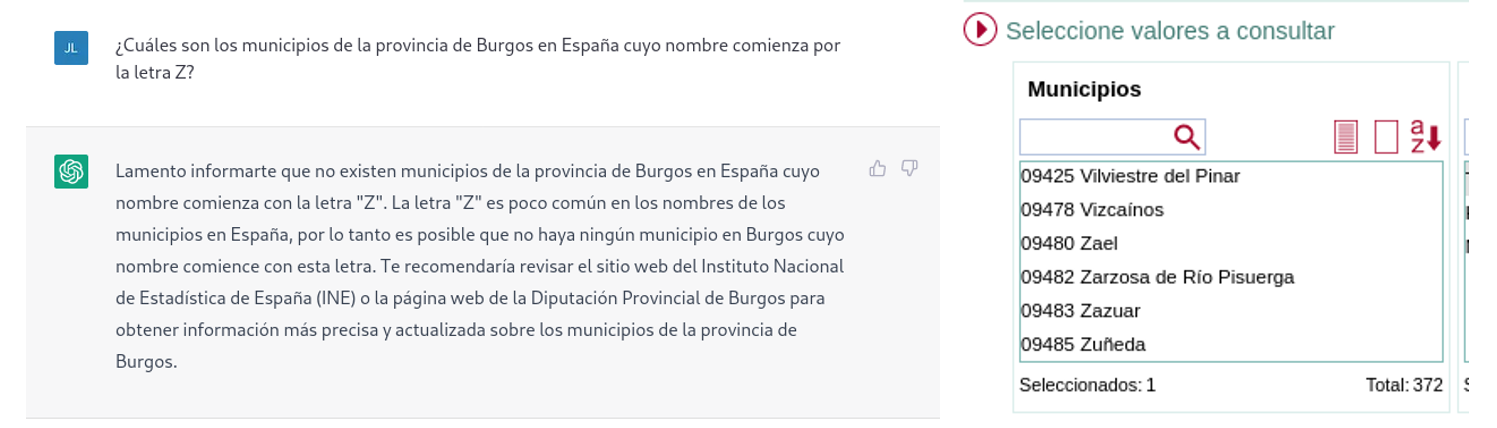

If we ask more specific questions, such as asking for a list of the municipalities in the province of Burgos that begin with the letter "G", we get answers that are not completely correct, as is typical of a technology that is still in its infancy.

The correct answer should contain six municipalities: Galbarros, La Gallega, Grijalba, Grisaleña, Gumiel de Hizán and Gumiel del Mercado. However, the answer we have obtained only contains the first four and includes localities in the province of Guadalajara (Gualda), municipalities in the province of Valladolid (Gallegos de Hornija) or localities in the province of Burgos that are not municipalities (Galarde). In this case, we can also turn to the open dataset to get the correct answer.

Next, we ask ChatGPT for the list of municipalities beginning with the letter Z in the same province. ChatGPT tells us that there are none, reasoning the answer, when in fact there are four:

As can be seen from the examples above, we can see how open data can indeed contribute to technological evolution and thus improve the performance of Open AI's artificial intelligence. However, given its current state of maturity, it is still too early to see the optimal use of open data to answer more complex questions.

Therefore, for a generative AI model to be effective, it is necessary to have a large amount of high quality and diverse data, and open data is a valuable source of knowledge for this purpose.

In future versions of the model, we will probably be able to see how open data will acquire a much more important role in the composition of the training corpus, achieving a significant improvement in the quality of the factual answers.

Content prepared by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Although it may seem like a novel concept, the term 'artificial intelligence' was already coined in the mid-twentieth century. However, its popularity has experienced a vertiginous increase in recent years thanks to the increase in data volumes or the application of advanced algorithms in everyday situations, among other aspects.

Artificial intelligence allows machines to learn from experience to perform various tasks in a human-like manner. To do so, its training techniques often rely on deep learning and natural language processing (NLP), among others. By employing these technologies in the service of AI, machines can be trained to carry out very specific tasks such as processing large amounts of data or pattern recognition in them.

What is artificial intelligence?

The European Commission defines artificial intelligence as the ability of a machine to imitate some of the characteristics of human intelligence such as learning, reasoning or creativity. To do so, computers analyze available information in order to achieve specific objectives.

Artificial intelligence is also composed of subfields based on technologies such as Machine Learning or Deep Learning. Both activities aim to build systems that have the ability to solve problems without the need for human intervention.

What is the role of open data in artificial intelligence?

To ensure the proper development of artificial intelligence, open data is extremely important. This is because its algorithms must be trained with high-quality data that is readily available, as reflected in various state and European-level strategies and guidelines such as the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy, the European Regulation on Artificial Intelligence, and the White Paper on Artificial Intelligence.

Examples of use cases of artificial intelligence

The application of artificial intelligence allows many fields to achieve improvements in various processes, services, or applications. Some examples are:

- Health: AI allows for the identification of different pathologies through the processing of medical images, for example, through QMenta, which processes and visualizes images to perform analysis of brain data.

- Environment: AI allows for more efficient forest management. An example is Forecast, which offers tools for decision-making by forest managers.

- Economy: AI is used to optimize the management of tenders, as with the Arbatro Tender tool, designed to find and choose the most suitable public tenders for each company.

- Tourism: AI allows for the development of virtual tourism assistants like Castilla y León Gurú, which features advanced NLP functions, detection of points of interest in images, and use of geolocated context.

- Culture: thanks to AI, it is possible to generate original texts and summaries of existing ones through natural language processing. MarIA has been the first Spanish-language artificial intelligence to achieve this.

- Advertising and content writing: AI systems such as Chat GPT allow for the development of texts based on specific requests.

As we can see, there are a multitude of use cases that combine artificial intelligence and open data to contribute to the progress and well-being of society. We recommend that you check out this informative infographic where we provide more details, as well as some interesting articles like this one on Dall-E so that you can expand your knowledge.

Moreover, if you want to learn more about related use cases, discover the report "Emerging Technologies and Open Data: Artificial Intelligence," which includes a practical step-by-step case study on image recognition and classification.

Click on the infographic to see it in full size and access the links:

Puedes ver la infografía en tamaño completo haciendo click aquí.

For years now we have been announcing that Artificial Intelligence is undergoing one of its most prolific, exciting periods. A time when applications and use cases begin to be seen in which human intelligence merges with artificial intelligence. Some occupations are changing forever. Journalists and writers now have software tools that can write for them. Content creators - images or video - can ask the machine to create for them just by saying a phrase. In this post we have taken a closer look at this last example. We have been able to test Dall-e 2 and the results have left us speechless.

Introduction

Nowadays, in the technological community worldwide, there is an underlying buzz, a collective excitement of all lovers of digital technologies and in particular of artificial intelligence. On several occasions we have mentioned the innovations of the company Open AI in this communication space. We have written several articles where we talk about the GPT-3 algorithm and what it is capable of in the field of natural language processing. Recently, OpenAI has been doing away with the waiting lists (on which many of us had been enrolled for a long time) to allow us to test in a limited way the capabilities of the GPT-3 algorithm implemented in different types of applications.

Example of the multiple applications of GPT-3 in the field of natural language.

We recommend our readers to try out the text completion tool with which, merely by providing a short sentence, the AI completes the text with several paragraphs indistinguishable from human writing. The last few days have been hectic with crowds of people testing the ChatGPT-3 tool. The degree of naturalness with which AI can have a conversation is simply amazing. The results are having an impact on a wide variety of use cases, such as support for software developers. ChatGPT-3 has been able to programme simple code routines or algorithms just from a description in natural language of what you want to programme. However, the result is even more impressive when we realise that AI is capable of correcting its own programming errors.

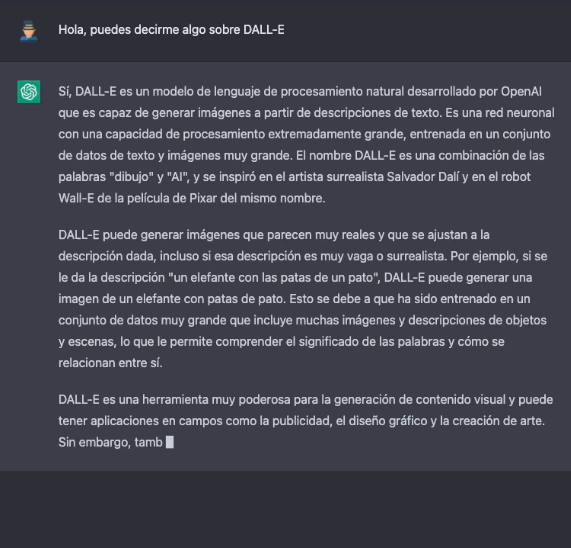

DALL-E

Leaving aside the capabilities of generating natural language indistinguishable from that written by a human, now let's take a look the main theme of this post. One of the most amazing applications of the AI of OpenAI is the solution known as DALL-E. What better way to introduce DALL-E than ask ChatGPT-3 what DALL-E is.

The more formal description of DALL-E, according to its own website, is as follows:

DALL·E is a 12-billion parameter version of GPT-3 trained to generate images from text descriptions. DALL-E has a diverse set of capabilities, including creating anthropomorphised versions of animals and objects, combining unrelated concepts in plausible ways, rendering text, and applying transformations to existing images..

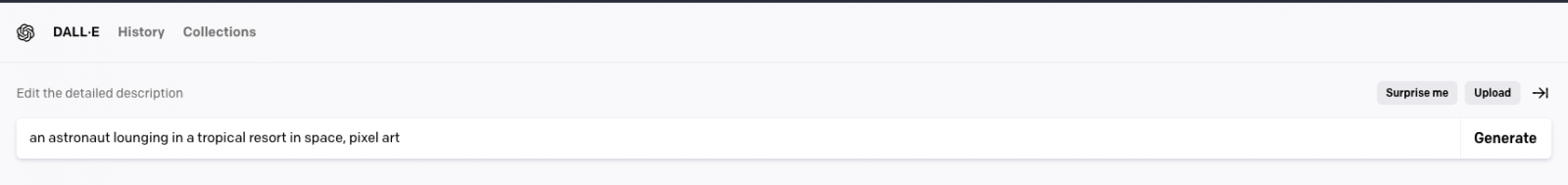

There is currently a second version of the algorithm. DALL-E 2 capable of generating more realistic and precise images with a resolution 4 times higher. The tool for trying out DALL-E is available here https://labs.openai.com/. To use it, we first need to create an OpenAI account that will allow us to play with all the tools of the company. When we access the test website we can write our own text or ask the tool to generate random descriptions of images in natural language to create images. For example, by clicking the Surprise me button:

The web generates this random description for us: an astronaut lounging in a tropical resort in space, pixel art

And this is the result:

We repeat: An expressive oil painting of a basketball player dunking, depicted as an explosion of a nebula

We can assure you that the exercise is somewhat addictive and we admit that some of us have spent hours of our weekends playing with the descriptions and waiting, over and over again, for the amazing result.

About DALL-E 2 training

DALL-E 2 (arXiv:2204.06125) is a refined version of the original DALL-E system (arXiv:2102.12092). To train the original DALL-E model, which contains 12 billion parameters, a set of 250 million text-image pairs was used (publicly available online). This data set is a mixture of several prior datasets comprising: Conceptual Captions by Google; Wikipedia's text-image pairs and a filtered subset of YFCC100M.

DALL-E 2 trivia

Some interesting things besides the tests that we can do to generate our own images. OpenAI has created a specific Github repository which describes the risks and limitations of DALL-E. At the site it is reported, for example, that, for the time being, the use of DALL-E is limited to non-commercial purposes. So it is not possible to make any commercial use of the images generated. In other words, they cannot be sold or licensed under any circumstances. In this regard, all the images generated by DALL-E include a distinctive mark that lets you know that they have been generated by AI. At the Github site we can find loads of information about the generation of explicit content, the risks related with the bias that AI can introduce into the generation of images and the inappropriate uses of DALL-E such as the harassment, bullying or exploitation of individuals.

Along national lines, MarIA

Along national lines, after months of tests and adjustments, MarIA, the first supermassive artificial intelligence, has seen the light of day, trained with open data from the web archives of the National Library of Spain (BNE) and thanks to the computing resources of the National Supercomputing Centre. With regard to this post, MarIA has been trained using the GPT-2 algorithm which we have talked about many months ago in this space. To carry out the MarIA training, 135 billion previous words from the National Library's documentary bank have been used with a total volume of 570 Gigabytes of information.

Conclusions

As the days and weeks go by since the general opening of the APIs and the OpenIA tools, there has been a torrent of publications on all kinds of media, social media and specialised blogs about the capabilities and possibilities of Chat GPT-3 and DALL-E. I don't think that at this time anyone is capable of predicting the potential commercial, scientific and social applications of this technology. What is clear is that many of us think that OpenAI has shown only a sample of what it is capable of and it seems that we may be on the verge of a historic milestone in the development of AI after many years of overexpectations and unfulfilled promises. We will continue to report on the progress of GTP-3, but for the time being, all we can do is to keep enjoying, playing and learning with the simple tools that we have at our disposal!

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, an expert in Digital Transformation.

The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

After several months competing, on 20 October the open data contest organised by the EU came to an end. The EU Datathon is a contest that gives data developers and scientists the chance to demonstrate, through their creativity, the potential of open data.

Although in this post you can find out in detail about the winning projects, in this case we would like to highlight the participation of two Spanish developers whose initiatives were chosen as semi-finalists from amongst the 156 proposals submitted at the start.

In an edition that broke the attendance records, both in terms of the number of contestants and the countries of origin, Antonio Moneo and Manuel Jose García represented Spain with two projects which stood out for their innovative nature regarding the reuse of open data.

Using Artificial Intelligence to optimally solve public tenders

Manuel José García has a PhD in Telecommunications Engineering from the University of Oviedo and currently works as a data scientist at the technology consultancy NTT Data. After scooping up first prize in the Euskadi Open Data contest in 2020, García decided to take part in the European hackathon, making the most of what he had learned from the research carried out in his PhD thesis and which gave rise to the project 'Detection of irregular tenders in Spain through big data analytics and artificial intelligence'.

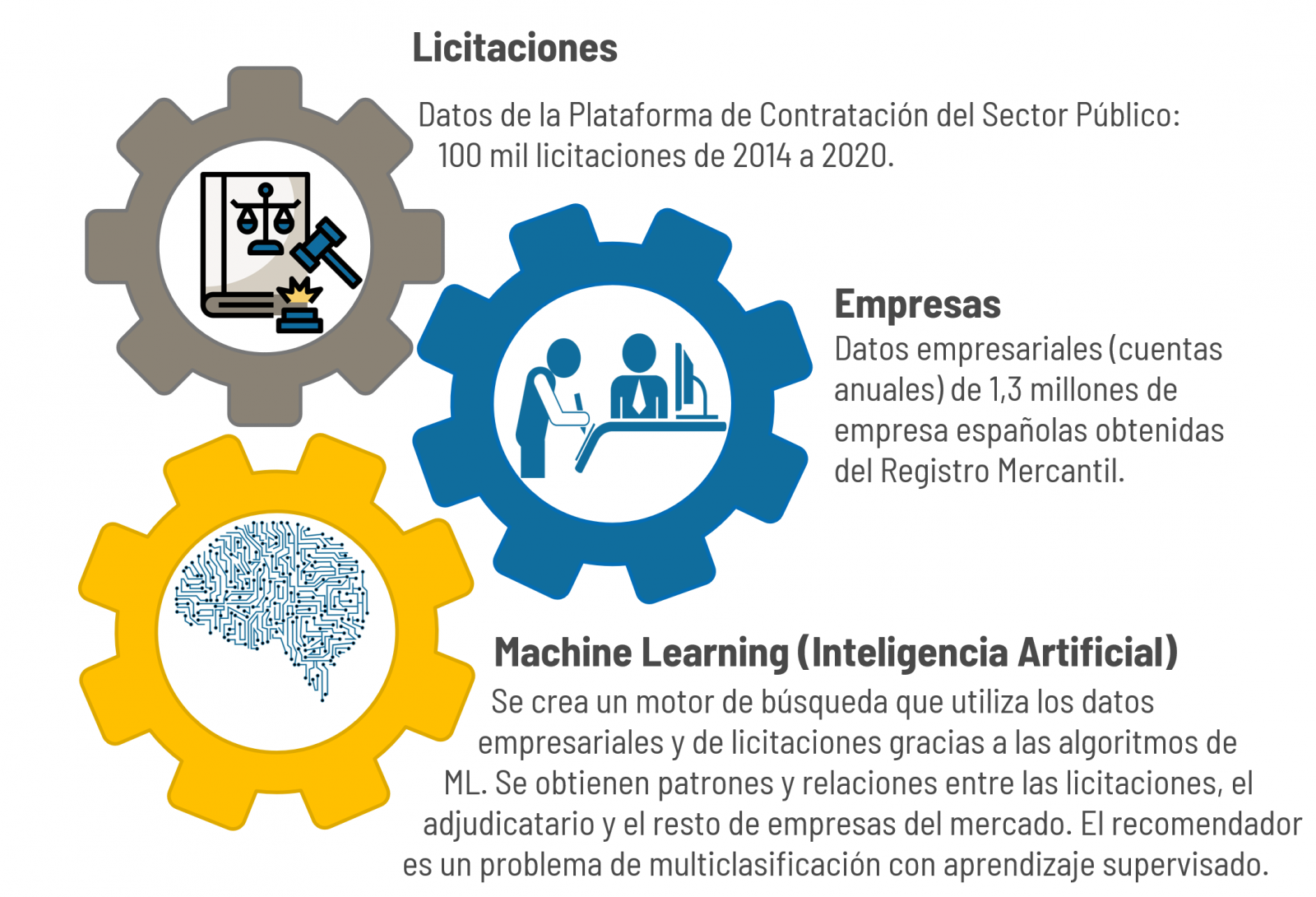

"It is an initiative that uses Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (AI) to analyse the data from public tenders and to automatically recommend those companies that can best undertake the tender. With this in mind, a search engine is created for companies that can carry out a tender and a form is filled out describing the details that characterise the public tender. From that point onwards, the programme seeks the most suitable companies to carry out the project”, describes Manuel Jose García, who adds that the list of companies recommended by tender is achieved thanks to the fact that the AI model has been trained with the history of hundreds of thousands of tenders and winning companies from the past, learning what type of companies win tenders and what characteristics they have.

An essential requirement in order to participate in the European datathon is to use information from the data catalogues that both Europe and Spain make available to the public at a national, regional and local level. In the specific case of Manuel José García, his project has been developed using the public tender data available at the Public Procurement Platforms.

“The project has been developed using two types of data sources. On the one hand, the public and free data of the tenders and, on the other, the business data required to search for and characterise the companies present in the search engine. In particular, the annual accounts that companies must submit to the Registrar of Companies have been used. These data are public but paid and it is vogue to make them free as they are data managed by a public entity”, comments the data scientist.

In fact, it is precisely this point related with the data from the Registrar of Companies which entailed a challenge to take the project forward: “Getting structured data from public tenders is complicated, since the open data format of the Spanish Procurement Platform is difficult to handle. In addition, it is necessary to carry out thorough cleaning of the data because their quality is low”, he points out.

In his opinion, if public administrations wish to promote the reuse of open data, “They must promote the culture of data. In other words, to be aware of the importance of the data they handle and store and, in turn, be proactive to exploit said data and make them available to third parties”.

Architecture and open data to make the Sustainable Development Goals visible

In addition to being the Director of Change Management and Advanced Analysis at BBVA, Antonio Moneo was also a semi-finalist in the latest edition of the European datathon thanks to a project that merges art with the dissemination of open data.

“Tangible Data is an initiative whose goal is to convert emblematic data series into physical sculptures and thereby be able to lend visibility to issues such as climate change, inequality or the transparency of our governments. Against a backdrop of excess information and a growing digital divide, it is essential to rely on the physical environment to explain what is happening in the world", explains Antonio Moneo and he stresses that "representing data in a sculpture allows us to present a challenge from an objective, respectful perspective”.

When selecting the open data sets, Moneo was clear that he wanted to make visible the realities and statistics related with the Sustainable Development Objectives so that his project would fulfil the social purpose that led him to participate in the datathon: “We use open data from reliable sources and properly licensed with Creative Commons or MIT criteria. Sometimes we have used a private data source, but our objective is to enhance the information that is already available. In addition, we usually use the data in the manner in which they are published and only apply some transformations such as the smoothing of the curves with moving averages that allow us to make the sculptures more pleasant to the touch and, self-evidently, techniques to create volumes in three dimensions that are the basis for the sculptures," he observed.

Hence, to carry out Tangible Data it has been necessary, on the one hand, to build a physical structure and, on the other, to make it invite the user to move to the digital realm where, at the end of the day, the information they seek to make visible can be found. “The first step is to design a 3D model in virtual format which we send off to be produced locally, using the FabLabs network. Later, we include a QR code in the sculpture that allows the audience to know in depth the meaning of the data that it reflects”, explained the promoter of the project.

Developing such an ambitious project, both from a physical point of view and from an informative perspective, is no easy task. The thing is, it is not only a matter of circumventing the design of the sculpture as such, but also of finding the necessary data to transfer the reality that it is sought to represent: “Comparability is one of the biggest challenges we have encountered because, in many cases, the most relevant data for measuring the environment are not always comparable. Sometimes we find data at a regional level, sometimes at a national or local level, but it is not always possible to find all the information you need. This is why, in order to solve this challenge, we have invested more time in searching for data and, in many cases, the initial idea about a sculpture has been modified because we could not find data of sufficient quality”, he went on to say.

Moneo also commented that the other major difficulty that has marked the development of the project has been to access updated data. “Updating is always a critical issue, but right now it is even more so. The consequences of COVID, the war in Ukraine and the current energy crisis paint a very different world from the one we encountered in 2015, when the sustainable development objectives were signed. For example, it is estimated that as a consequence of the pandemic, between 70 and 150 million people will fall into the extreme poverty segment (with less than 1.9 dollars a day). This change, bucking the trend of the last three decades, is not reflected in the World Bank statistics yet as they only go up to 2019. It would this seem that that very relevant data reflect a distorted reality”, he concluded.

A positive review of his time in the EU Datathon

Despite not having reached the final that would have allowed them to compete for part of the total prize, which amounted to 200,000 euros, the two participants agreed that their experience in the datathon has been more than positive. So, whilst Manuel José García believes that "the European Commission must continue to commit to these initiatives so that people are aware of the value of data and the challenges that they can solve”, for his part, Antonio Moneo points out that “this type of action motivates the agencies that drive the data and those who are developing to improve the impact of data on society”.

What's more, both participants have managed to stimulate their professional curiosity thanks to this challenge, whilst simultaneously testing the potential and quality of their respective work vis-à-vis European data experts.

In this post we have described step-by-step a data science exercise in which we try to train a deep learning model with a view to automatically classifying medical images of healthy and sick people.

Diagnostic imaging has been around for many years in the hospitals of developed countries; however, there has always been a strong dependence on highly specialised personnel. From the technician who operates the instruments to the radiologist who interprets the images. With our current analytical capabilities, we are able to extract numerical measures such as volume, dimension, shape and growth rate (inter alia) from image analysis. Throughout this post we will try to explain, through a simple example, the power of artificial intelligence models to expand human capabilities in the field of medicine.

This post explains the practical exercise (Action section) associated with the report “Emerging technologies and open data: introduction to data science applied to image analysis”. Said report introduces the fundamental concepts that allow us to understand how image analysis works, detailing the main application cases in various sectors and highlighting the role of open data in their implementation.

Previous projects

However, we could not have prepared this exercise without the prior work and effort of other data science lovers. Below we have provided you with a short note and the references to these previous works.

- This exercise is an adaptation of the original project by Michael Blum on the STOIC2021 - disease-19 AI challenge. Michael's original project was based on a set of images of patients with Covid-19 pathology, along with other healthy patients to serve as a comparison.

- In a second approach, Olivier Gimenez used a data set similar to that of the original project published in a competition of Kaggle. This new dataset (250 MB) was considerably more manageable than the original one (280GB). The new dataset contained just over 1,000 images of healthy and sick patients. Olivier's project code can be found at the following repository.

Datasets

In our case, inspired by these two amazing previous projects, we have built an educational exercise based on a series of tools that facilitate the execution of the code and the possibility of examining the results in a simple way. The original data set (chest x-ray) comprises 112,120 x-ray images (front view) from 30,805 unique patients. The images are accompanied by the associated labels of fourteen diseases (where each image can have multiple labels), extracted from associated radiological reports using natural language processing (NLP). From the original set of medical images we have extracted (using some scripts) a smaller, delimited sample (only healthy people compared with people with just one pathology) to facilitate this exercise. In particular, the chosen pathology is pneumothorax.

If you want further information about the field of natural language processing, you can consult the following report which we already published at the time. Also, in the post 10 public data repositories related to health and wellness the NIH is referred to as an example of a source of quality health data. In particular, our data set is publicly available here.

Tools

To carry out the prior processing of the data (work environment, programming and drafting thereof), R (version 4.1.2) and RStudio (2022-02-3) was used. The small scripts to help download and sort files have been written in Python 3.

Accompanying this post, we have created a Jupyter notebook with which to experiment interactively through the different code snippets that our example develops. The purpose of this exercise is to train an algorithm to be able to automatically classify a chest X-ray image into two categories (sick person vs. non-sick person). To facilitate the carrying out of the exercise by readers who so wish, we have prepared the Jupyter notebook in the Google Colab environment which contains all the necessary elements to reproduce the exercise step-by-step. Google Colab or Collaboratory is a free Google tool that allows you to programme and run code on python (and also in R) without the need to install any additional software. It is an online service and to use it you only need to have a Google account.

Logical flow of data analysis

Our Jupyter Notebook carries out the following differentiated activities which you can follow in the interactive document itself when you run it on Google Colab.

- Installing and loading dependencies.

- Setting up the work environment

- Downloading, uploading and pre-processing of the necessary data (medical images) in the work environment.

- Pre-visualisation of the loaded images.

- Data preparation for algorithm training.

- Model training and results.

- Conclusions of the exercise.

Then we carry out didactic review of the exercise, focusing our explanations on those activities that are most relevant to the data analysis exercise:

- Description of data analysis and model training

- Modelling: creating the set of training images and model training

- Analysis of the training result

- Conclusions

Description of data analysis and model training

The first steps that we will find going through the Jupyter notebook are the activities prior to the image analysis itself. As in all data analysis processes, it is necessary to prepare the work environment and load the necessary libraries (dependencies) to execute the different analysis functions. The most representative R package of this set of dependencies is Keras. In this article we have already commented on the use of Keras as a Deep Learning framework. Additionally, the following packages are also required: htr; tidyverse; reshape2; patchwork.

Then we have to download to our environment the set of images (data) we are going to work with. As we have previously commented, the images are in remote storage and we only download them to Colab at the time we analyse them. After executing the code sections that download and unzip the work files containing the medical images, we will find two folders (No-finding and Pneumothorax) that contain the work data.

Once we have the work data in Colab, we must load them into the memory of the execution environment. To this end, we have created a function that you will see in the notebook called process_pix(). This function will search for the images in the previous folders and load them into the memory, in addition to converting them to grayscale and normalising them all to a size of 100x100 pixels. In order not to exceed the resources that Google Colab provides us with for free, we limit the number of images that we load into memory to 1000 units. In other words, the algorithm will be trained with 1000 images, including those that it will use for training and those that it will use for subsequent validation.

Once we have the images perfectly classified, formatted and loaded into memory, we carry out a quick visualisation to verify that they are correct. We obtain the following results:

Self-evidently, in the eyes of a non-expert observer, there are no significant differences that allow us to draw any conclusions. In the steps below we will see how the artificial intelligence model actually has a better clinical eye than we do.

Modelling

Creating the training image set

As we mentioned in the previous steps, we have a set of 1000 starting images loaded in the work environment. Until now, we have had classified (by an x-ray specialist) those images of patients with signs of pneumothorax (on the path "./data/Pneumothorax") and those patients who are healthy (on the path "./data/No -Finding")

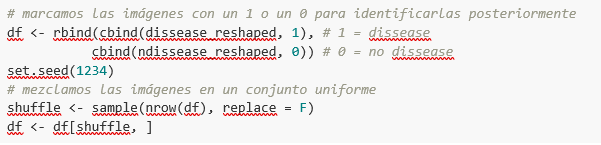

The aim of this exercise is precisely to demonstrate the capacity of an algorithm to assist the specialist in the classification (or detection of signs of disease in the x-ray image). With this in mind, we have to mix the images to achieve a homogeneous set that the algorithm will have to analyse and classify using only their characteristics. The following code snippet associates an identifier (1 for sick people and 0 for healthy people) so that, later, after the algorithm's classification process, it is possible to verify those that the model has classified correctly or incorrectly.

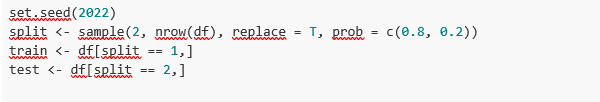

So, now we have a uniform “df” set of 1000 images mixed with healthy and sick patients. Next, we split this original set into two. We are going to use 80% of the original set to train the model. In other words, the algorithm will use the characteristics of the images to create a model that allows us to conclude whether an image matches the identifier 1 or 0. On the other hand, we are going to use the remaining 20% of the homogeneous mixture to check whether the model, once trained, is capable of taking any image and assigning it 1 or 0 (sick, not sick).

Model training

Right, now all we have left to do is to configure the model and train with the previous data set.

Before training, you will see some code snippets which are used to configure the model that we are going to train. The model we are going to train is of the binary classifier type. This means that it is a model that is capable of classifying the data (in our case, images) into two categories (in our case, healthy or sick). The model selected is called CNN or Convolutional Neural Network. Its very name already tells us that it is a neural networks model and thus falls under the Deep Learning discipline. These models are based on layers of data features that get deeper as the complexity of the model increases. We would remind you that the term deep refers precisely to the depth of the number of layers through which these models learn.

Note: the following code snippets are the most technical in the post. Introductory documentation can be found here, whilst all the technical documentation on the model's functions is accessible here.

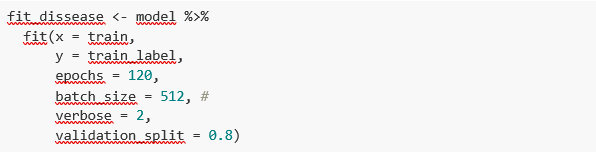

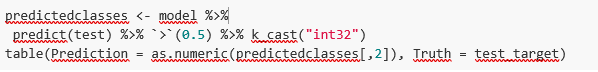

Finally, after configuring the model, we are ready to train the model. As we mentioned, we train with 80% of the images and validate the result with the remaining 20%.

Training result

Well, now we have trained our model. So what's next? The graphs below provide us with a quick visualisation of how the model behaves on the images that we have reserved for validation. Basically, these figures actually represent (the one in the lower panel) the capability of the model to predict the presence (identifier 1) or absence (identifier 0) of disease (in our case pneumothorax). The conclusion is that when the model trained with the training images (those for which the result 1 or 0 is known) is applied to 20% of the images for which the result is not known, the model is correct approximately 85% (0.87309) of times.

Indeed, when we request the evaluation of the model to know how well it classifies diseases, the result indicates the capability of our newly trained model to correctly classify 0.87309 of the validation images.

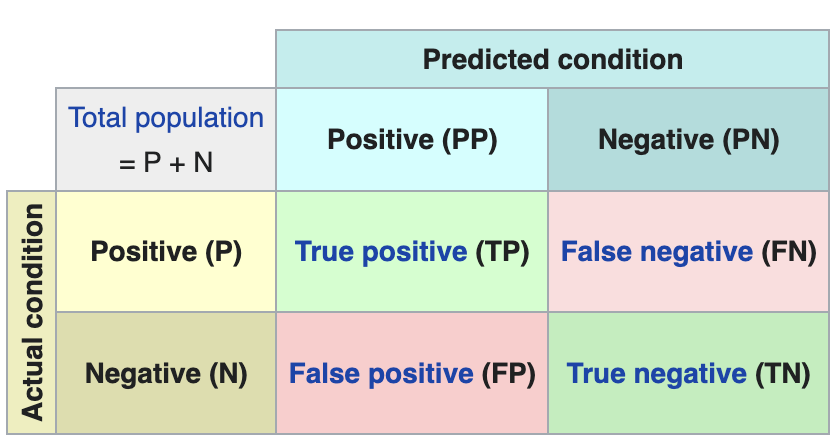

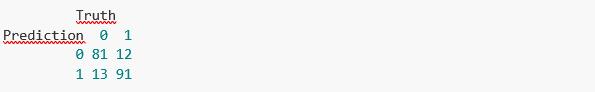

Now let’s make some predictions about patient images. In other words, once the model has been trained and validated, we wonder how it is going to classify the images that we are going to give it now. As we know "the truth" (what is called the ground truth) about the images, we compare the result of the prediction with the truth. To check the results of the prediction (which will vary depending on the number of images used in the training) we use that which in data science is called the confusion matrix. The confusion matrix:

- Places in position (1,1) the cases that DID have disease and the model classifies as "with disease"

- Places in position (2,2), the cases that did NOT have disease and the model classifies as "without disease"

In other words, these are the positions in which the model "hits" its classification.

In the opposite positions, in other words, (1,2) and (2,1) are the positions in which the model is "wrong". So, position (1,2) are the results that the model classifies as WITH disease and the reality is that they were healthy patients. Position (2,1), the very opposite.

Explanatory example of how the confusion matrix works. Source: Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Confusion_matrix

In our exercise, the model gives us the following results:

In other words, 81 patients had this disease and the model classifies them correctly. Similarly, 91 patients were healthy and the model also classifies them correctly. However, the model classifies as sick 13 patients who were healthy. Conversely, the model classifies 12 patients who were actually sick as healthy. When we add the hits of the 81+91 model and divide it by the total validation sample, we obtain 87% accuracy of the model.

Conclusions

In this post we have guided you through a didactic exercise consisting of training an artificial intelligence model to carry out chest x-ray imaging classifications with the aim of determining automatically whether someone is sick or healthy. For the sake of simplicity, we have chosen healthy patients and patients with pneumothorax (only two categories) previously diagnosed by a doctor. The journey we have taken gives us an insight into the activities and technologies involved in automated image analysis using artificial intelligence. The result of the training affords us a reasonable classification system for automatic screening with 87% accuracy in its results. Algorithms and advanced image analysis technologies are, and will increasingly be, an indispensable complement in multiple fields and sectors, such as medicine. In the coming years, we will see the consolidation of systems which naturally combine the skills of humans and machines in expensive, complex or dangerous processes. Doctors and other workers will see their capabilities increased and strengthened thanks to artificial intelligence. The joining of forces between machines and humans will allow us to reach levels of precision and efficiency never seen before. We hope that through this exercise we have helped you to understand a little more about how these technologies work. Don't forget to complete your learning with the rest of the materials that accompany this post.

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, an expert in Digital Transformation.The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

We present a new report in the series 'Emerging Technologies and Open Data', by Alejandro Alija. The aim of these reports is to help the reader understand how various technologies work, what is the role of open data in them and what impact they will have on our society. This series includes monographs on data analysis techniques such as natural language analysis and predictive analytics. This new volume of the series analyzes the key aspects of data analysis applied to images and, through this exercise, Artificial Intelligence applied to the identification and classification of diseases by means of medical radio imaging, delves into the more practical side of the monograph.

Image analysis adopts different names and ways of referring to it. Some of the most common are visual analytics, computer vision or image processing. The importance of this type of analysis is of great relevance nowadays, since many of the most modern algorithmic techniques of artificial intelligence have been designed specifically for this purpose. Some of its applications can be seen in our daily lives, such as the identification of license plates to access a parking lot or the digitization of scanned text to be manipulated.

The report introduces the fundamental concepts that allow us to understand how image analysis works, detailing the main application cases in various sectors. After a brief introduction by the author, which will serve as a basis for contextualizing the subject matter, the full report is presented, following the traditional structure of the series:

- Awareness. The Awareness section explains the key concepts of image analysis techniques. Through this section, readers can find answers to questions such as: how are images manipulated as data, how are images classified, and discover some of the most prominent applications in image analysis.

- Inspire. The Inspire section takes a detailed look at some of the main use cases in sectors as diverse as agriculture, industry and real estate. It also includes examples of applications in the field of medicine, where the author shows some particularly important challenges in this area.

- Action: In this case, the Action section has been published in notebook format, separately from the theoretical report. It shows a practical example of Artificial Intelligence applied to the identification and classification of diseases using medical radio imaging. This post includes a step-by-step explanation of the exercise. The source code is available so that readers can learn and experiment by themselves the intelligent analysis of images.

Below, you can download the report - Awareness and Inspire sections - in pdf and word (reusable version).

The demand for professionals with skills related to data analytics continues to grow and it is already estimated that just the industry in Spain would need more than 90,000 data and artificial intelligence professionals to boost the economy. Training professionals who can fill this gap is a major challenge. Even large technology companies such as Google, Amazon or Microsoft are proposing specialised training programmes in parallel to those proposed by the formal education system. And in this context, open data plays a very relevant role in the practical training of these professionals, as open data is often the only possibility to carry out real exercises and not just simulated ones.

Moreover, although there is not yet a solid body of research on the subject, some studies already suggest positive effects derived from the use of open data as a tool in the teaching-learning process of any subject, not only those related to data analytics. Some European countries have already recognised this potential and have developed pilot projects to determine how best to introduce open data into the school curriculum.

In this sense, open data can be used as a tool for education and training in several ways. For example, open data can be used to develop new teaching and learning materials, to create real-world data-based projects for students or to support research on effective pedagogical approaches. In addition, open data can be used to create opportunities for collaboration between educators, students and researchers to share best practices and collaborate on solutions to common challenges.

Projects based on real-world data

A key contribution of open data is its authenticity, as it is a representation of the enormous complexity and even flaws of the real world as opposed to artificial constructs or textbook examples that are based on much simpler assumptions.

An interesting example in this regard is documented by Simon Fraser University in Canada in their Masters in Publishing where most of their students come from non-STEM university programmes and therefore had limited data handling skills. The project is available as an open educational resource on the OER Commons platform and aims to help students understand that metrics and measurement are important strategic tools for understanding the world around us.

By working with real-world data, students can develop story-building and research skills, and can apply analytical and collaborative skills in using data to solve real-world problems. The case study conducted with the first edition of this open data-based OER is documented in the book "Open Data as Open Educational Resources - Case studies of emerging practice". It shows that the opportunity to work with data pertaining to their field of study was essential to keep students engaged in the project. However, it was dealing with the messiness of 'real world' data that allowed them to gain valuable learning and new practical skills.

Development of new learning materials

Open datasets have a great potential to be used in the development of open educational resources (OER), which are free digital teaching, learning and research materials, as they are published under an open licence (Creative Commons) that allows their use, adaptation and redistribution for non-commercial uses according to UNESCO's definition.

In this context, although open data are not always OER, we can say that they become OER when are used in pedagogical contexts. Open data used as an educational resource facilitates students to learn and experiment by working with the same datasets used by researchers, governments and civil society. It is a key component for students to develop analytical, statistical, scientific and critical thinking skills.

It is difficult to estimate the current presence of open data as part of OER but it is not difficult to find interesting examples within the main open educational resource platforms. On the Procomún platform we can find interesting examples such as Learning Geography through the evolution of agrarian landscapes in Spain, which builds a Webmap for learning about agrarian landscapes in Spain on the ArcGIS Online platform of the Complutense University of Madrid. The educational resource uses specific examples from different autonomous communities using photographs or geolocated still images and its own data integrated with open data. In this way, students work on the concepts not through a mere text description but with interactive resources that also favour the improvement of their digital and spatial competences.

On the OER Commons platform, for example, we find the resource "From open data to civic engagement", which is aimed at audiences from secondary school upwards, with the objective of teaching them to interpret how public money is spent in a given regional, local area or neighbourhood. It is based on the well-known projects to analyse public budgets "Where do my taxes go?", available in many parts of the world as a result of the transparency policies of public authorities. This resource could be easily ported to Spain, as there are numerous "Where do my taxes go?" projects, such as the one maintained by Fundación Civio.

Data-related skills

When we refer to training and education in data-related skills, we are actually referring to a very broad area that is also very difficult to master in all its facets. In fact, it is common for data-related projects to be tackled in teams where each member has a specialised role in one of these areas. For example, it is common to distinguish at least data cleaning and preparation, data modelling and data visualisation as the main activities performed in a data science and artificial intelligence project.

In all cases, the use of open data is widely adopted as a central resource in the projects proposed for the acquisition of any of these skills. The well-known data science community Kaggle organises competitions based on open datasets contributed to the community and which are an essential resource for real project-based learning for those who want to acquire data-related skills. There are other subscription-based proposals such as Dataquest or ProjectPro but in all cases they use real datasets from multiple general open data repositories or knowledge area specific repositories.

Open data, as in other areas, has not yet developed its full potential as a tool for education and training. However, as can be seen in the programme of the latest edition of the OER Conference 2022, there are an increasing number of examples of open data playing a central role in teaching, new educational practices and the creation of new educational resources for all kinds of subjects, concepts and skills

Content written by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.