On September 8, the webinar \"Geospatial Trends 2023: Opportunities for data.europa.eu\" was held, organized by the Data Europa Academy and focused on emerging trends in the geospatial field. Specifically, the online conference addressed the concept of GeoAI (Geospatial Artificial Intelligence), which involves the application of artificial intelligence (AI) combined with geospatial data.

Next, we will analyze the most cutting-edge technological developments of 2023 in this field, based on the knowledge provided by the experts participating in the aforementioned webinar.

What is GeoAI?

The term GeoAI, as defined by Kyoung-Sook Kim, co-chair of the GeoAI Working Group of the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC), refers to \"a set of methods or automated entities that use geospatial data to perceive, construct (automate), and optimize spaces in which humans, as well as everything else, can safely and efficiently carry out their geographically referenced activities.\"

GeoAI allows us to create unprecedented opportunities, such as:

- Extracting geospatial data enriched with deep learning: Automating the extraction, classification, and detection of information from data such as images, videos, point clouds, and text.

- Conducting predictive analysis with machine learning: Facilitating the creation of more accurate prediction models, pattern detection, and automation of spatial algorithms.

- Improving the quality, uniformity, and accuracy of data: Streamlining manual data generation workflows through automation to enhance efficiency and reduce costs.

- Accelerating the time to gain situational knowledge: Assisting in responding more rapidly to environmental needs and making more proactive, data-driven decisions in real-time.

- Incorporating location intelligence into decision-making: Offering new possibilities in decision-making based on data from the current state of the area that needs governance or planning.

Although this technology gained prominence in 2023, it was already discussed in the 2022 geospatial trends report, where it was indicated that integrating artificial intelligence into spatial data represents a great opportunity in the world of open data and the geospatial sector.

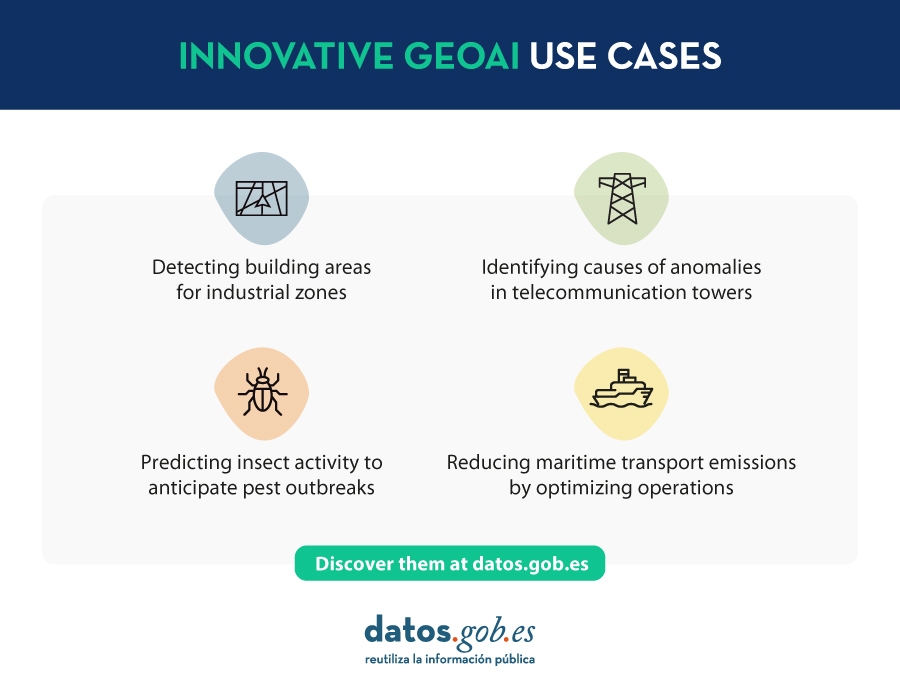

Use Cases of GeoAI

During the Geospatial Trends 2023 conference, companies in the GIS sector, Con terra and 52ºNorth, shared practical examples highlighting the use of GeoAI in various geospatial applications.

Examples presented by Con terra included:

- KINoPro: A research project using GeoAI to predict the activity of the \"black arches\" moth and its impact on German forests.

- Anomaly detection in cell towers: Using a neural network to detect causes of anomalies in towers that can affect the location in emergency calls.

- Automated analysis of construction areas: Aiming to detect building areas for industrial zones using OpenData and satellite imagery.

On the other hand, 52ºNorth presented use cases such as MariData, which seeks to reduce emissions from maritime transport by using GeoAI to calculate optimal routes, considering ship position, environmental data, and maritime traffic regulations. They also presented KI:STE, which applies artificial intelligence technologies in environmental sciences for various projects, including classifying Sentinel-2 images into (un)protected areas.

These projects highlight the importance of GeoAI in various applications, from predicting environmental events to optimizing maritime transport routes. They all emphasize that this technology is a crucial tool for addressing complex problems in the geospatial community.

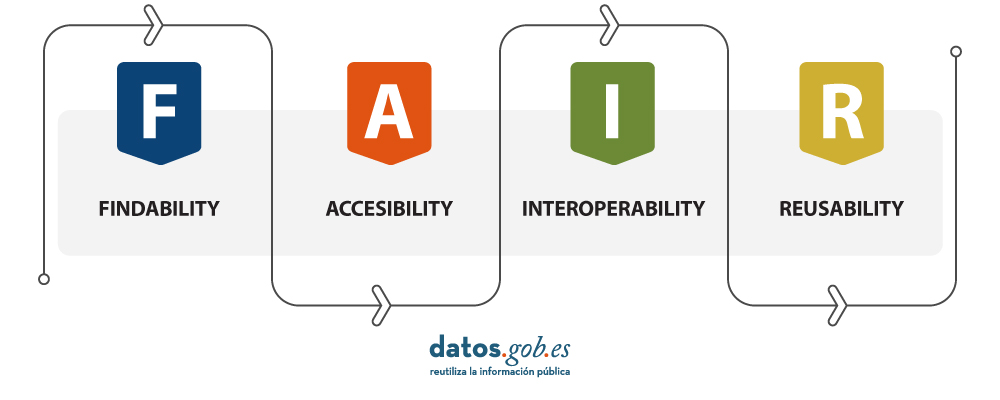

GeoAI not only represents a significant opportunity for the spatial sector but also tests the importance of having open data that adheres to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). These principles are essential for GeoAI projects as they ensure transparent, efficient, and ethical access to information. By adhering to FAIR principles, datasets become more accessible to researchers and developers, fostering collaboration and continuous improvement of models. Additionally, transparency and the ability to reuse open data contribute to building trust in results obtained through GeoAI projects.

Reference

| Reference video | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YYiMQOQpk8A |

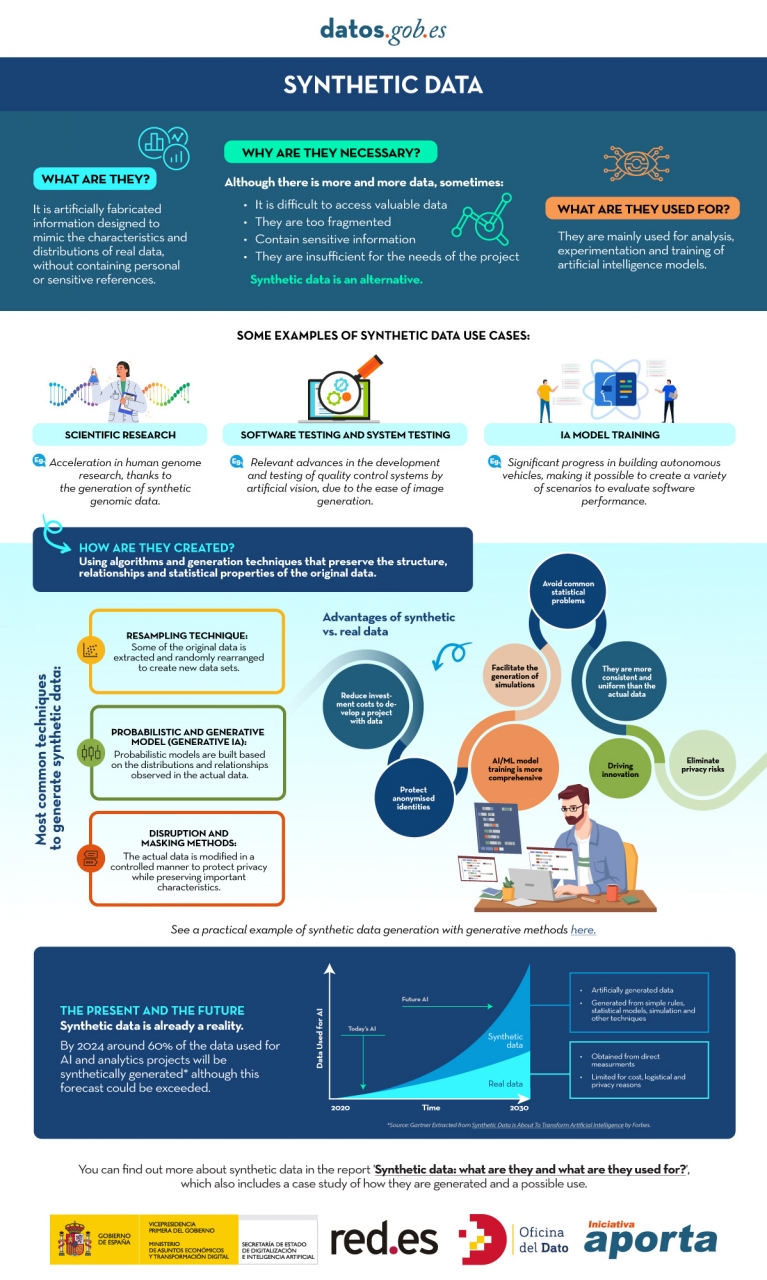

In the era of data, we face the challenge of a scarcity of valuable data for building new digital products and services. Although we live in a time when data is everywhere, we often struggle to access quality data that allows us to understand processes or systems from a data-driven perspective. The lack of availability, fragmentation, security, and privacy are just some of the reasons that hinder access to real data.

However, synthetic data has emerged as a promising solution to this problem. Synthetic data is artificially created information that mimics the characteristics and distributions of real data, without containing personal or sensitive information. This data is generated using algorithms and techniques that preserve the structure and statistical properties of the original data.

Synthetic data is useful in various situations where the availability of real data is limited or privacy needs to be protected. It has applications in scientific research, software and system testing, and training artificial intelligence models. It enables researchers to explore new approaches without accessing sensitive data, developers to test applications without exposing real data, and AI experts to train models without the need to collect all the real-world data, which is sometimes simply impossible to capture within reasonable time and cost.

There are different methods for generating synthetic data, such as resampling, probabilistic and generative modeling, and perturbation and masking methods. Each method has its advantages and challenges, but overall, synthetic data offers a secure and reliable alternative for analysis, experimentation, and AI model training.

It is important to highlight that the use of synthetic data provides a viable solution to overcome limitations in accessing real data and address privacy and security concerns. Synthetic data allows for testing, algorithm training, and application development without exposing confidential information. However, ensuring the quality and fidelity of synthetic data is crucial through rigorous evaluations and comparisons with real data.

In this report, we provide an introductory overview of the discipline of synthetic data, illustrating some valuable use cases for different types of synthetic data that can be generated. Autonomous vehicles, DNA sequencing, and quality controls in production chains are just a few of the cases detailed in this report. Furthermore, we highlight the use of the open-source software SDV (Synthetic Data Vault), developed in the academic environment of MIT, which utilizes machine learning algorithms to create tabular synthetic data that imitates the properties and distributions of real data. We present a practical example in a Google Colab environment to generate synthetic data about fictional customers hosted in a fictional hotel. We follow a workflow that involves preparing real data and metadata, training the synthesizer, and generating synthetic data based on the learned patterns. Additionally, we apply anonymization techniques to protect sensitive data and evaluate the quality of the generated synthetic data.

In summary, synthetic data is a powerful tool in the data era, as it allows us to overcome the scarcity and lack of availability of valuable data. With its ability to mimic real data without compromising privacy, synthetic data has the potential to transform the way we develop AI projects and conduct analysis. As we progress in this new era, synthetic data is likely to play an increasingly important role in generating new digital products and services.

If you want to know more about the content of this report, you can watch the interview with its author.

Below, you can download the full report, the executive summary and a presentation-summary.

Digital technology and algorithms have revolutionised the way we live, work and communicate. While promising efficiency, accuracy and convenience, these technologies can exacerbate prejudice and social inequalities exacerbate prejudice and social inequalities and create new forms of exclusion and create new forms of exclusion. Thus, invisibilisation and discrimination, which have always existed, take on new forms in the age of algorithms.

Lack of interest and data leads to algorithmic invisibilisation, leading to two types of algorithmic neglect. The first of these is among the world's underserved, which includes the millions who do not have a smartphone or a bank account millions who do not have a smartphone or a bank account, and are thus on the margins of the platform economy and who are therefore on the margins of the platform economy and, for algorithms, do not exist. The second type of algorithmic abandonment includes individuals or groups who are victims of the failure of the algorithmic system, as was the case with SyRI(Systeem Risico Indicatie)SyRI(Systeem Risico Indicatie) in the Netherlands that unfairly singled out some 20,000 families from low socio-economic backgrounds for tax fraud, leading many to ruin by 2021. The algorithm, which the algorithm, which was declared illegal by a court in The Hague months later, was applied in the country's poorest neighbourhoodsthe algorithm, which was declared illegal by a court in The Hague months later, was applied in the country's poorest neighbourhoods the algorithm, which was declared illegal by a court in The Hague months later, was applied in the poorest neighbourhoods of the country and blocked many families with more than one nationality from receiving the social benefits to which they were entitled because of their socio-economic status.

Beyond the example in the Dutch public system, invisibilisation and discrimination can also originate in the private sector. One example is Amazon's amazon's job posting algorithm which showed a bias against women by learning from historical data - i.e. incomplete data because it did not include a large and representative universe - leading Amazon to abandon the project. which showed a bias against women by learning from historical data - i.e. incomplete data because it did not include a large and representative universe - leading Amazon to abandon the project. Another example is Apple Card, a credit card backed by Goldman Sachs, which was also singled out when its algorithm was found to offer more favourable credit limits to men than to women.

In general, invisibility and algorithmic discrimination, in any field, can lead to unequal access to resources and exacerbate social and economic exclusion.

Making decisions based on algorithms

Data and algorithms are interconnected components in computing and information processing. Data serve as a basis, but can be unstructured, with excessive variability and incompleteness. Algorithms are instructions or procedures designed to process and structure this data and extract meaningful information, patterns or results.

The quality and relevance of the data directly impacts the effectiveness of the algorithms, as they rely on the data inputs to generate results. Hence, the principle "rubbish in, rubbish out"which summarises the idea that if poor quality, biased or inaccurate data enters a system or process, the result will also be of poor quality or inaccurate. On the other hand, well-designed well-designed algorithms can enhance the value of data by revealing hidden relationships or making by revealing hidden relationships or making predictions.

This symbiotic relationship underscores the critical role that both data and algorithms play in driving technological advances, enabling informed decision making, and This symbiotic relationship underscores the critical role that both data and algorithms play in driving technological advances, enabling informed decision making, and fostering innovation.

Algorithmic decision making refers to the process of using predefined sets of instructions or rules to analyse data and make predictions to aid decision making. Increasingly, it is being applied to decisions that have to do with social welfare social welfare and the provision of commercial services and products through platforms. This is where invisibility or algorithmic discrimination can be found.

Increasingly, welfare systems are using data and algorithms to help make decisions on issues such as who should receive what kind of care and who is at risk. These algorithms consider different factors such as income, family or household size, expenditures, risk factors, age, sex or gender, which may include biases and omissions.

That is why the That is why the Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, warned in a report to the UN General Assembly that the uncautious adoption of these can lead to dystopian social welfare dystopian social welfare. In such a dystopian welfarestate , algorithms are used to reduce budgets, reduce the number of beneficiaries, eliminate services, introduce demanding and intrusive forms of conditionality, modify behaviour, impose sanctions and "reverse the notion that the state is accountable".

Algorithmic invisibility and discrimination: Two opposing concepts

Although data and algorithms have much in common, algorithmic invisibility and discrimination are two opposing concepts. Algorithmic invisibility refers to gaps in data sets or omissions in algorithms, which result in inattentions in the application of benefits or services. In contrast, algorithmic discrimination speaks to hotspots that highlight specific communities or biased characteristics in datasets, generating unfairness.

That is, algorithmic invisibilisation occurs when individuals or groups are absent from datasets, making it impossible to address their needs. For example, integrating data on women with disabilities into social decision-making can be vital for the inclusion of women with disabilities in society. Globally, women are more vulnerable to algorithmic invisibilisation than men, as they have less access to digital technology have less access to digital technology and leave fewer digital traces.

Opaque algorithmic systems that incorporate stereotypes can increase invisibilisation and discrimination by hiding or targeting vulnerable individuals or populations. An opaque algorithmic system is one that does not allow access to its operation.

On the other hand, aggregating or disaggregating data without careful consideration of the consequences can result in omissions or errors result in omissions or errors. This illustrates the double-edged nature of accounting; that is, the ambivalence of technology that quantifies and counts, and that can serve to improve people's lives, but also to harm them.

Discrimination can arise when algorithmic decisions are based on historical data, which usually incorporate asymmetries, stereotypes and injustices, because more inequalities existed in the past. The "rubbish in, rubbish out" effect occurs if the data is skewed, as is often the case with online content. Also, biased or incomplete databases can be incentives for algorithmic discrimination. Selection biases may arise when facial recognition data, for example, is based on the features of white men, while the users are dark-skinned women, or on online content generated by a minority of agentswhich makes generalisation difficult.

As can be seen, tackling invisibility and algorithmic discrimination is a major challenge that can only be solved through awareness-raising and collaboration between institutions, campaigning organisations, businesses and research.

Content prepared by Miren Gutiérrez, PhD and researcher at the University of Deusto, expert in data activism, data justice, data literacy and gender disinformation.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) is a United Nations agency whose purpose is to contribute to peace and security in the world through education, science, culture and communication. In order to achieve its objective, this organisation usually establishes guidelines and recommendations such as the one published on 5 July 2023 entitled 'Open data for AI: what now?'

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic the UNESCO highlights a number of lessons learned:

- Policy frameworks and data governance models must be developed, supported by sufficient infrastructure, human resources and institutional capacities to address open data challenges, in order to be better prepared for pandemics and other global challenges.

- The relationship between open data and AI needs to be further specified, including what characteristics of open data are necessary to make it "AI-Ready".

- A data management, collaboration and sharing policy should be established for research, as well as for government institutions that hold or process health-related data, while ensuring data privacy through anonymisation and anonymisation data privacy should be ensured through anonymisation and anonymisation.

- Government officials who handle data that are or may become relevant to pandemics may need training to recognise the importance of such data, as well as the imperative to share them.

- As much high quality data as possible should be collected and collated. The data needs to come from a variety of credible sources, which, however, must also be ethical, i.e. it must not include data sets with biases and harmful content, and it must be collected only with consent and not in a privacy-invasive manner. In addition, pandemics are often rapidly evolving processes, so continuous updating of data is essential.

- These data characteristics are especially mandatory for improving inadequate AI diagnostic and predictive tools in the future. Efforts are needed to convert the relevant data into a machine-readable format, which implies the preservation of the collected data, i.e. cleaning and labelling.

- A wide range of pandemic-related data should be opened up, adhering to the FAIR principles.

- The target audience for pandemic-related open data includes research and academia, decision-makers in governments, the private sector for the development of relevant products, but also the public, all of whom should be informed about the available data.

- Pandemic-related open data initiatives should be institutionalised rather than ad hoc, and should therefore be put in place for future pandemic preparedness. These initiatives should also be inclusive and bring together different types of data producers and users.

- The beneficial use of pandemic-related data for AI machine learning techniques should also be regulated to prevent misuse for the development of artificial pandemics, i.e. biological weapons, with the help of AI systems.

The UNESCO builds on these lessons learned to establish Recommendations on Open Science by facilitating data sharing, improving reproducibility and transparency, promoting data interoperability and standards, supporting data preservation and long-term access.

As we increasingly recognise the role of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the availability and accessibility of data is more crucial than ever, which is why UNESCO is conducting research in the field of AI to provide knowledge and practical solutions to foster digital transformation and build inclusive knowledge societies.

Open data is the main focus of these recommendations, as it is seen as a prerequisite for planning, decision-making and informed interventions. The report therefore argues that Member States must share data and information, ensuring transparency and accountability, as well as opportunities for anyone to make use of the data.

UNESCO provides a guide that aims to raise awareness of the value of open data and specifies concrete steps that Member States can take to open their data. These are practical, but high-level steps on how to open data, based on existing guidelines. Three phases are distinguished: preparation, data opening and follow-up for re-use and sustainability, and four steps are presented for each phase.

It is important to note that several of the steps can be carried out simultaneously, i.e. not necessarily consecutively.

Step 1: Preparation

- Develop a data management and sharing policy: A data management and sharing policy is an important prerequisite for opening up data, as such a policy defines the governments' commitment to share data. The Open Data Institute suggests the following elements of an open data policy:

- A definition of open data, a general statement of principles, an outline of the types of data and references to any relevant legislation, policy or other guidance.

- Governments are encouraged to adhere to the principle "as open as possible, as closed as necessary". If data cannot be opened for legal, privacy or other reasons, e.g. personal or sensitive data, this should be clearly explained.

In addition, governments should also encourage researchers and the private sector in their countries to develop data management and sharing policies that adhere to the same principles.

- Collect and collate high quality data: Existing data should be collected and stored in the same repository, e.g. from various government departments where it may have been stored in silos. Data must be accurate and not out of date. Furthermore, data should be comprehensive and should not, for example, neglect minorities or the informal economy. Data on individuals should be disaggregated where relevant, including by income, sex, age, race, ethnicity, migration status, disability and geographic location.

- Develop open data capabilities: These capacities address two groups:

- For civil servants, it includes understanding the benefits of open data by empowering and enabling the work that comes with open data.

- For potential users, it includes demonstrating the opportunities of open data, such as its re-use, and how to make informed decisions.

- Prepare data for AI: If data is not only to be used by humans, but can also feed AI systems, it must meet a few more criteria to be AI-ready.

- The first step in this regard is to prepare the data in a machine-readable format.

- Some formats are more conducive to readability by artificial intelligence systems than others.

- Data must also be cleaned and labelled, which is often time-consuming and therefore costly.

The success of an AI system depends on the quality of the training data, including its consistency and relevance. The required amount of training data is difficult to know in advance and must be controlled by performance checks. The data should cover all scenarios for which the AI system has been created.

Step 2: Open the data

- Select the datasets to be opened: The first step in opening the data is to decide which datasets are to be opened. The criteria in favour of openness are:

- If there have been previous requests to open these data

- Whether other governments have opened up this data and whether this has led to beneficial uses of the data.

Openness of data must not violate national laws, such as data privacy laws.

- Open the datasets legally: Before opening the datasets, the relevant government has to specify exactly under which conditions, if any, the data can be used. In publishing the data, governments may choose the license that best suits their objectives, such as the creative Commons and Open. To support the licence selection the European Commission makes available JLA - Compatibility Checkera tool that supports this decision

- Open the datasets technically: The most common way to open the data is to publish it in electronic format for download on a website, and APIs must be in place for the consumption of this data, either by the government itself or by a third party.

Data should be presented in a format that allows for localisation, accessibility, interoperability and re-use, thus complying with the FAIR principles.

In addition, the data could also be published in a data archive or repository, which should be, according to the UNESCO Recommendation, supported and maintained by a well-established academic institution, learned society, government agency or other non-profit organisation dedicated to the common good that allows for open access, unrestricted distribution, interoperability and long-term digital archiving and preservation.

- Create a culture driven by open data: Experience has shown that, in addition to legal and technical openness of data, at least two other things need to be achieved to achieve an open data culture:

- Government departments are often not used to sharing data and it has been necessary to create a mindset and educate them to this end.

- Furthermore, data should, if possible, become the exclusive basis for decision-making; in other words, decisions should be based on data.

- In addition, cultural changes are required on the part of all staff involved, encouraging proactive disclosure of data, which can ensure that data is available even before it is requested.

Step 3: Monitoring of re-use and sustainability

- Support citizen participation: Once the data is open, it must be discoverable by potential users. This requires the development of an advocacy strategy, which may include announcing the openness of the data in open data communities and relevant social media channels.

Another important activity is early consultation and engagement with potential users, who, in addition to being informed about open data, should be encouraged to use and re-use it and to stay involved.

- Supporting international engagement: International partnerships would further enhance the benefits of open data, for example through south-south and north-south collaboration. Particularly important are partnerships that support and build capacity for data reuse, whether using AI or not.

- Support beneficial AI participation: Open data offers many opportunities for AI systems. To realise the full potential of data, developers need to be empowered to make use of it and develop AI systems accordingly. At the same time, the abuse of open data for irresponsible and harmful AI applications must be avoided. A best practice is to keep a public record of what data AI systems have used and how they have used it.

- Maintain high quality data: A lot of data quickly becomes obsolete. Therefore, datasets need to be updated on a regular basis. The step "Maintain high quality data" turns this guideline into a loop, as it links to the step "Collect and collate high quality data".

Conclusions

These guidelines serve as a call to action by UNESCO on the ethics of artificial intelligence. Open data is a necessary prerequisite for monitoring and achieving sustainable development monitoring and achieving sustainable development.

Due to the magnitude of the tasks, governments must not only embrace open data, but also create favourable conditions for beneficial AI engagement that creates new insights from open data for evidence-based decision-making.

If UNESCO Member States follow these guidelines and open their data in a sustainable way, build capacity, as well as a culture driven by open data, we can achieve a world where data is not only more ethical, but where applications on this data are more accurate and beneficial to humanity.

References

https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/open-data-ai-what-now

Author : Ziesche, Soenke , ISBN : 978-92-3-100600-5

Content prepared by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

Sign up for SEMIC 2023 and discover the interoperable Europe in the era of artificial intelligence. According to the forecasts of the European Commission, by 2025, the global volume of data will have increased by 530%, and in this context, it is crucial to ensure data interoperability and reuse. Thus, the European Union is working on creating a digital model that promotes data sharing while ensuring people's privacy and data interoperability.

The European Data Strategy includes the launch of common and interoperable data spaces in strategic sectors. In this context, various initiatives have emerged to discuss the processes, standards, and tools suitable for data management and exchange, which also serve to promote a culture of information and reuse. One of these initiatives is SEMIC, the most important interoperability conference in Europe, whose 2023 edition will take place on October 18th in Madrid, organized by the European Commission in collaboration with the Spanish Presidency of the Council of the European Union.

SEMIC 2023, which can also be attended virtually, focuses on 'Interoperable Europe in the AI era.' The sessions will address data spaces, digital governance, data quality assurance, generative artificial intelligence, and code as law, among other aspects. Information about the proposal for an Interoperable Europe Law will also be presented.

Pre-Workshops

Attendees will have the opportunity to learn about specific use cases where public sector interoperability and artificial intelligence have mutually benefited. Although SEMIC 2023 will take place on October 18th, the day before, three interesting workshops will also be held, which can be attended both in-person and virtually:

- Artificial Intelligence in Policy Design for the Digital Age and in Legal Text Writing: This workshop will explore how AI-driven tools can assist policymakers in public policy formulation. Different tools, such as the Policy Analysis Prototype (SeTA) or intelligent functionalities for legal drafting (LEOS), will be discussed.

- Large Language Models in Support of Interoperability: This session will explore the methods and approaches proposed for using large language models and AI technology in the context of semantic interoperability. It will focus on the state of LLM and its application to semantic clustering, data discovery, and terminology expansion, among other applications supporting semantic interoperability.

- European Register of Public Sector Semantic Models: This workshop will define actions to create an entry point for connecting national collections of semantic assets.

Interactions Between Artificial Intelligence, Interoperability, and Semantics

The main SEMIC 2023 conference program includes roundtable discussions and various working sessions that will run in parallel. The first session will address Estonia's experience as one of the first European countries to implement AI in the public sector and its pioneering role in interoperability.

In the morning, an interesting roundtable will be held on the potential of artificial intelligence to support interoperability. Speakers from different EU Member States will present success stories and challenges related to deploying AI in the public sector.

In the second half of the morning, three parallel sessions will take place:

- Crafting Policies for the Digital Age and Code as Law: This session will identify the main challenges and opportunities in the field of AI and interoperability, focusing on 'code as law' as a paradigm. Special attention will be given to semantic annotation in legislation.

- Interconnecting Data Spaces: This session will address the main challenges and opportunities in the development of data spaces, with a special focus on interoperability solutions. It will also discuss synergies between the Data Spaces Support Center (DSSC) and the European Commission's DIGIT specifications and tools.

- Automated Public Services: This session will provide an approach to automating access to public services with the help of AI and chatbots.

In the afternoon, three more parallel sessions will be held:

- Knowledge Graphs, Semantics, and AI: This session will demonstrate how traditional semantics benefit from AI.

- Data Quality in Generative and General-Purpose AI: This session will review the main data quality issues in the EU and discuss strategies to overcome them.

- Trustworthy AI for Public Sector Interoperability: This session will discuss the opportunities for using AI for interoperability in the public sector and the transparency and reliability challenges of AI systems.

In the afternoon, there will also be a roundtable discussion on the upcoming challenges, addressing the technological, social, and political implications of advances in AI and interoperability from the perspective of policy actions. Following this panel, the closing sessions will take place.

The previous edition, held in Brussels, brought together over 1,000 professionals from 60 countries, both in-person and virtually. Therefore, SEMIC 2023 presents an excellent opportunity to learn about the latest trends in interoperability in the era of artificial intelligence.

You can register here: https://semic2023.eu/registration/

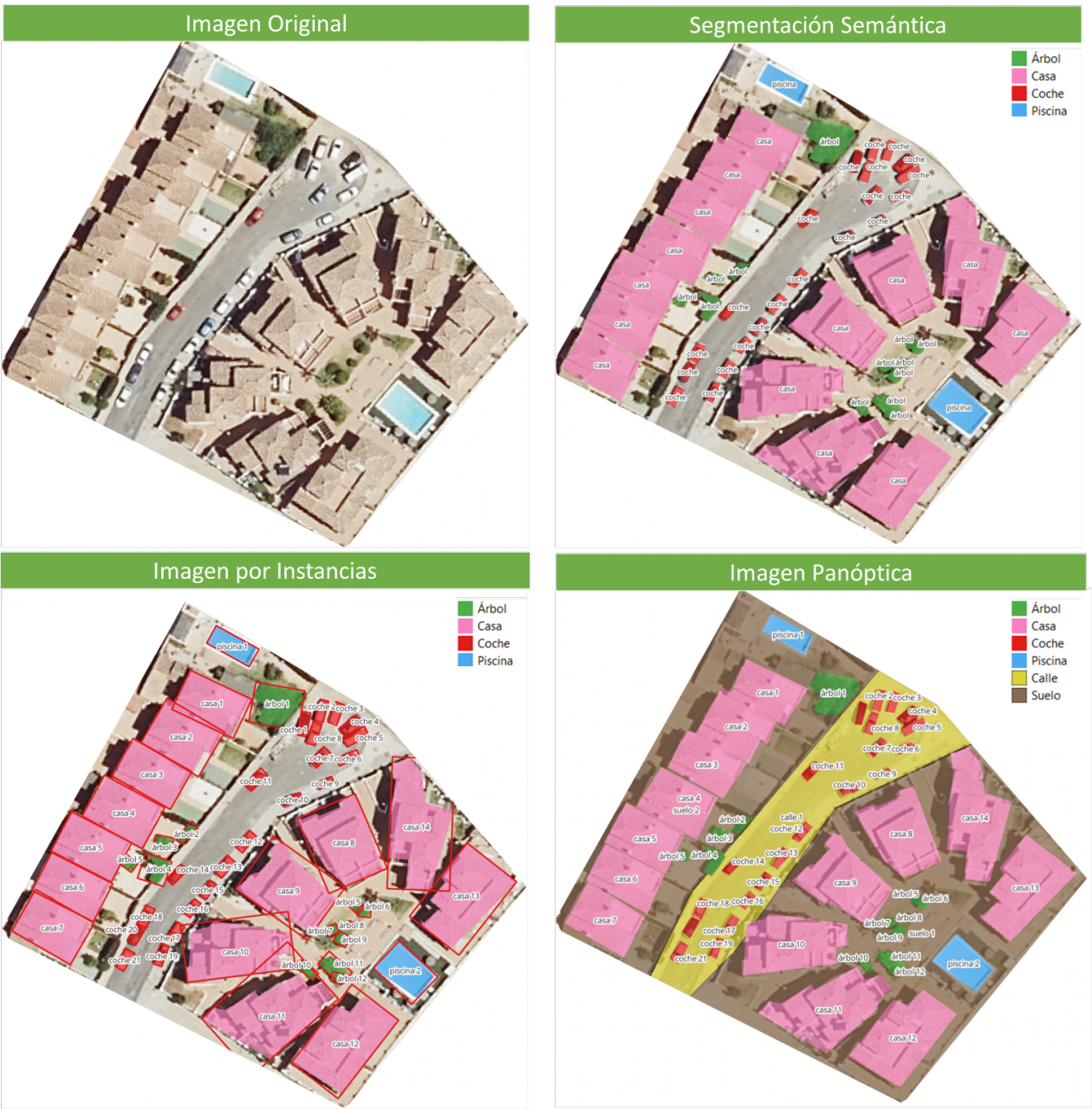

Image segmentation is a method that divides a digital image into subgroups (segments) to reduce its complexity, thus facilitating its processing or analysis. The purpose of segmentation is to assign labels to pixels to identify objects, people, or other elements in the image.

Image segmentation is crucial for artificial vision technologies and algorithms, but it is also used in many applications today, such as medical image analysis, autonomous vehicle vision, face recognition and detection, and satellite image analysis, among others.

Segmenting an image is a slow and costly process. Therefore, instead of processing the entire image, a common practice is image segmentation using the mean-shift approach. This procedure employs a sliding window that progressively traverses the image, calculating the average pixel values within that region.

This calculation is done to determine which pixels should be incorporated into each of the delineated segments. As the window advances along the image, it iteratively recalibrates the calculation to ensure the suitability of each resulting segment.

When segmenting an image, the factors or characteristics primarily considered are:

-

Color: Graphic designers have the option to use a green-toned screen to ensure chromatic uniformity in the background of the image. This practice enables the automation of background detection and replacement during the post-processing stage.

-

Edges: Edge-based segmentation is a technique that identifies the edges of various objects in a given image. These edges are identified based on variations in contrast, texture, color, and saturation.

-

Contrast: The image is processed to distinguish between a dark figure and a light background based on high-contrast values.

These factors are applied in different segmentation techniques:

-

Thresholds: Divide the pixels based on their intensity relative to a specified threshold value. This method is most suitable for segmenting objects with higher intensity than other objects or backgrounds.

-

Regions: Divide an image into regions with similar characteristics by grouping pixels with similar features.

-

Clusters: Clustering algorithms are unsupervised classification algorithms that help identify hidden information in the images. The algorithm divides the images into groups of pixels with similar characteristics, separating elements into groups and grouping similar elements in these groups.

-

Watersheds: This process transforms grayscale images, treating them as topographic maps, where the brightness of pixels determines their height. This technique is used to detect lines forming ridges and watersheds, marking the areas between watershed boundaries.

Machine learning and deep learning have improved these techniques, such as cluster segmentation, and have also generated new segmentation approaches that use model training to enhance program capabilities in identifying important features. Deep neural network technology is especially effective for image segmentation tasks.

Currently, there are different types of image segmentation, with the main ones being:

- Semantic Segmentation: Semantic image segmentation is a process that creates regions within an image and assigns semantic meaning to each of them. These objects, also known as semantic classes, such as cars, buses, people, trees, etc., have been previously defined through model training, where these objects are classified and labeled. The result is an image where pixels are classified into each located object or class.

- Instance Segmentation: Instance segmentation combines the semantic segmentation method (interpreting the objects in an image) with object detection (locating them within the image). As a result of this segmentation, objects are located, and each of them is individualized through a bounding box and a binary mask, determining which pixels within that window belong to the located object.

- Panoptic Segmentation: This is the most recent type of segmentation. It combines semantic segmentation and instance segmentation. This method can determine the identity of each object because it locates and distinguishes different objects or instances and assigns two labels to each pixel in the image: a semantic label and an instance ID. This way, each object is unique.

In the image, you can observe the results of applying different segmentations to a satellite image. Semantic segmentation returns a category for each type of identified object. Instance segmentation provides individualized objects along with their bounding boxes, and in panoptic segmentation, we obtain individualized objects and also differentiate the context, allowing for the detection of the ground and street regions.

Meta's New Model: SAM

In April 2023, Meta's research department introduced a new Artificial Intelligence (AI) model called SAM (Segment Anything Model). With SAM, image segmentation can be performed in three ways:

-

By selecting a point in the image, SAM will search for and distinguish the object intersecting with that point and find all identical objects in the image.

-

Using a bounding box, a rectangle is drawn on the image, and all objects found in that area are identified.

-

By using keywords, users can type a word in a console, and SAM can identify objects that match that word or explicit command in both images and videos, even if that information was not included in its training.

SAM is a flexible model that was trained on the largest dataset to date, called SA-1B, which includes 11 million images and 1.1 billion segmentation masks. Thanks to this data, SAM can detect various objects without the need for additional training.

Currently, SAM and the SA-1B dataset are available for non-commercial use and research purposes only. Users who upload their images are required to commit to using it solely for academic purposes. To try it out, you can visit this GitHub link.

In August 2023, the Image and Video Analysis Group of the Chinese Academy of Sciences released an update to their model called FastSAM, significantly reducing processing time with a 50 times faster execution speed compared to the original SAM model. This makes the model more practical for real-world usage. FastSAM achieved this acceleration by training on only 2% of the data used to train SAM, resulting in lower computational requirements while maintaining high accuracy.

SAMGEO: The Version for Analyzing Geospatial Data

The segment-geospatial package developed by Qiusheng Wu aims to facilitate the use of the Segment Anything Model (SAM) for geospatial data. For this purpose, two Python packages, segment-anything-py and segment-geospatial, have been developed, and they are available on PyPI and conda-forge.

The goal is to simplify the process of leveraging SAM for geospatial data analysis, allowing users to achieve it with minimal coding effort. These libraries serve as the basis for the QGIS Geo-SAM plugin and the integration of the model in ArcGIS Pro.

En la imagen se pueden observar los resultados de aplicar las distintas segmentaciones a una imagen satelital. La segmentación semántica devuelve una categoría por cada tipo de objeto identificado. La segmentación por instancia devuelve los objetos individualizados y la caja delimitadora y, en la segmentación panóptica, obtenemos los objetos individualizados y el contexto también diferenciado, pudiendo detectar el suelo y la región de calles.

Conclusions

In summary, SAM represents a significant revolution not only for the possibilities it opens in terms of editing photos or extracting elements from images for collages or video editing but also for the opportunities it provides to enhance computer vision when using augmented reality glasses or virtual reality headsets.

SAM also marks a revolution in spatial information acquisition, improving object detection through satellite imagery and facilitating the rapid detection of changes in the territory.

Content created by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies.

The content and viewpoints reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The combination and integration of open data with artificial intelligence (AI) is an area of work that has the potential to achieve significant advances in multiple fields and bring improvements to various aspects of our lives. The most frequently mentioned area of synergy is the use of open data as input for training the algorithms used by AI since these systems require large amounts of data to fuel their operations. This makes open data an essential element for AI development and utilizing it as input brings additional advantages such as increased equality of access to technology and improved transparency regarding algorithmic functioning.

Today, we can find open data powering algorithms for AI applications in diverse areas such as crime prevention, public transportation development, gender equality, environmental protection, healthcare improvement, and the creation of more friendly and liveable cities. All of these objectives are more easily attainable through the appropriate combination of these technological trends.

However, as we will see next, when envisioning the joint future of open data and AI, the combined use of both concepts can also lead to many other improvements in how we currently work with open data throughout its entire lifecycle. Let's review step by step how artificial intelligence can enrich a project with open data.

Utilizing AI to Discover Sources and Prepare Data Sets

Artificial intelligence can assist right from the initial steps of our data projects by supporting the discovery and integration of various data sources, making it easier for organizations to find and use relevant open data for their applications. Furthermore, future trends may involve the development of common data standards, metadata frameworks, and APIs to facilitate the integration of open data with AI technologies, further expanding the possibilities of automating the combination of data from diverse sources.

In addition to automating the guided search for data sources, AI-driven automated processes can be helpful, at least in part, in the data cleaning and preparation process. This can improve the quality of open data by identifying and correcting errors, filling gaps in the data, and enhancing its completeness. This would free scientists and data analysts from certain basic and repetitive tasks, allowing them to focus on more strategic activities such as developing new ideas and making predictions.

Innovative Techniques for Data Analysis with AI

One characteristic of AI models is their ability to detect patterns and knowledge in large amounts of data. AI techniques such as machine learning, natural language processing, and computer vision can easily be used to extract new perspectives, patterns, and knowledge from open data. Moreover, as technological development continues to advance, we can expect the emergence of even more sophisticated AI techniques specifically tailored for open data analysis, enabling organizations to extract even more value from it.

Simultaneously, AI technologies can help us go a step further in data analysis by facilitating and assisting in collaborative data analysis. Through this process, multiple stakeholders can work together on complex problems and find answers through open data. This would also lead to increased collaboration among researchers, policymakers, and civil society communities in harnessing the full potential of open data to address social challenges. Additionally, this type of collaborative analysis would contribute to improving transparency and inclusivity in decision-making processes.

The Synergy of AI and Open Data

In summary, AI can also be used to automate many tasks involved in data presentation, such as creating interactive visualizations simply by providing instructions in natural language or a description of the desired visualization.

On the other hand, open data enables the development of applications that, combined with artificial intelligence, can provide innovative solutions. The development of new applications driven by open data and artificial intelligence can contribute to various sectors such as healthcare, finance, transportation, or education, among others. For example, chatbots are being used to provide customer service, algorithms for investment decisions, or autonomous vehicles, all powered by AI. By using open data as the primary data source for these services, we would achieve higher

Finally, AI can also be used to analyze large volumes of open data and identify new patterns and trends that would be difficult to detect through human intuition alone. This information can then be used to make better decisions, such as what policies to pursue in each area to bring about the desired changes.

These are just some of the possible future trends at the intersection of open data and artificial intelligence, a future full of opportunities but at the same time not without risks. As AI continues to develop, we can expect to see even more innovative and transformative applications of this technology. This will also require closer collaboration between artificial intelligence researchers and the open data community in opening up new datasets and developing new tools to exploit them. This collaboration is essential in order to shape the future of open data and AI together and ensure that the benefits of AI are available to all in a fair and equitable way.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI), and ChatGPT in particular, has become one of the main topics of debate in recent months. This tool has even eclipsed other emerging technologies that had gained prominence in a wide range of fields (legal, economic, social and cultural). This is the case, for example, of web 3.0, the metaverse, decentralised digital identity or NFTs and, in particular, cryptocurrencies.

There is an unquestionable direct relationship between this type of technology and the need for sufficient and appropriate data, and it is precisely this last qualitative dimension that justifies why open data is called upon to play a particularly important role. Although, at least for the time being, it is not possible to know how much open data provided by public sector entities is used by ChatGPT to train its model, there is no doubt that open data is a key to improving their performance.

Regulation on the use of data by AI

From a legal point of view, AI is arousing particular interest in terms of the guarantees that must be respected when it comes to its practical application. Thus, various initiatives are being promoted that seek to specifically regulate the conditions for its use, among which the proposal being processed by the European Union stands out, where data are the object of special attention.

At the state level, Law 15/2022, of 12 July, on equal treatment and non-discrimination, was approved a few months ago. This regulation requires public administrations to promote the implementation of mechanisms that include guarantees regarding the minimisation of bias, transparency and accountability, specifically with regard to the data used to train the algorithms used for decision-making.

There is a growing interest on the part of the autonomous communities in regulating the use of data by AI systems, in some cases reinforcing guarantees regarding transparency. Also, at the municipal level, protocols are being promoted for the implementation of AI in municipal services in which the guarantees applicable to the data, particularly from the perspective of their quality, are conceived as a priority requirement.

The possible collision with other rights and legal interests: the protection of personal data

Beyond regulatory initiatives, the use of data in this context has been the subject of particular attention as regards the legal conditions under which it is admissible. Thus, it may be the case that the data to be used are protected by third party rights that prevent - or at least hinder - their processing, such as intellectual property or, in particular, the protection of personal data. This concern is one of the main motivations for the European Union to promote the Data Governance Regulation, a regulation that proposes technical and organisational solutions that attempt to make the re-use of information compatible with respect for these legal rights.

Precisely, the possible collision with the right to the protection of personal data has motivated the main measures that have been adopted in Europe regarding the use of ChatGPT. In this regard, the Garante per la Protezione dei Dati Personali has ordered a precautionary measure to limit the processing of Italian citizens' data, the Spanish Data Protection Agency has initiated ex officio inspections of OpenAI as data controller and, with a supranational scope, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPB) has created a specific working group.

The impact of the regulation on open data and re-use

The Spanish regulation on open data and re-use of public sector information establishes some provisions that must be taken into account by IA systems. Thus, in general, re-use will be admissible if the data has been published without conditions or, in the event that conditions are set, when they comply with those established through licences or other legal instruments; although, when they are defined, the conditions must be objective, proportionate, non-discriminatory and justified by a public interest objective.

As regards the conditions for re-use of information provided by public sector bodies, the processing of such information is only allowed if the content is not altered and its meaning is not distorted, and the source of the data and the date of its most recent update must be mentioned.

On the other hand, high-value datasets are of particular interest for these AI systems characterised by the intense re-use of third-party content given the massive nature of the data processing they carry out and the immediacy of the requests for information made by users. Specifically, the conditions established by law for the provision of these high-value datasets by public bodies mean that there are very few limitations and also that their re-use is greatly facilitated by the fact that the data must be freely available, be susceptible to automated processing, be provided through APIs and be provided in the form of mass downloading, where appropriate.

In short, considering the particularities of this technology and, therefore, the very unique circumstances in which the data are processed, it seems appropriate that the licences and, in general, the conditions under which public entities allow their re-use be reviewed and, where appropriate, updated to meet the legal challenges that are beginning to arise.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the "Innovation, Law and Technology" Research Group (iDerTec).

The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

In the process of analysing data and training machine learning models, it is essential to have an adequate dataset. Therefore, the questions arise: how should you prepare your datasets for machine learning and analytics, and how can you be confident that the data will lead to robust conclusions and accurate predictions?

The first thing to consider when preparing your data is to know the type of problem you are trying to solve. For example, if your intention is to create a machine learning model capable of recognising someone's emotional state from their facial expressions, you will need a dataset with images or videos of people's faces. Or, perhaps, the goal is to create a model that identifies unwanted emails. For this, you will need data in text format from emails.

Furthermore, the data required also depends on the type of algorithm you want to use. Supervised learning algorithms, such as linear regression or decision trees, require a field containing the true value of an outcome for the model to learn from. In addition to this true value, called the target, they require fields containing information about the observations, known as features. In contrast, unsupervised learning algorithms, such as k-means clustering or recommendation systems based on collaborative filtering, usually only need features.

However, finding the data is only half the job. Real-world datasets can contain all sorts of errors that can render all the work useless if they are not detected and corrected before starting. In this post, we'll introduce some of the main pitfalls that can be found in datasets for machine learning and analytics, as well as some ways in which the collaborative data science platform, Datalore, can help spot them quickly and remedy them.

Is the data representative of what you want to measure?

Most datasets for machine learning projects or analytics are not designed specifically for that purpose. In the absence of a metadata dictionary or an explanation of what the fields in the dataset mean, the user may have to figure out the unknown based on the information available to them.

One way to determine what features in a dataset measure is to check their relationships to other features. If two fields are assumed to measure similar things, one would expect them to be closely related. Conversely, if two domains measure very different things, you would expect them to be unrelated. These ideas are known as convergent and discriminant validity, respectively.

Another important thing to check is whether any of the traits are too closely related to the target audience. If this happens, it may indicate that this feature is accessing the same information as the target to be predicted. This phenomenon is known as feature leakage. If such data is used, there is a risk of artificially inflating the performance of the model.

In this sense, Datalore allows you to quickly scan the relationship between continuous variables by means of the correlation graph in the Visualise tab for a DataFrame. Another way to test these relationships is by using bar charts or cross tabulations, or effect size measures such as the coefficient of determination or Cramer's V.

Is the dataset properly filtered and cleaned?

Datasets can contain all kinds of inconsistencies that can negatively affect our models or analyses. Some of the most important indicators of dirty data are:

- Implausible values: This includes values that are out of range, such as negatives in a count variable or frequencies that are much higher or lower than expected for a particular field.

- Outliers: These are extreme values, which can represent anything from coding errors that occurred at the time the data were written, to rare but real values that lie outside the bulk of the other observations.

- Missing values: The pattern and amount of missing data determines the impact it will have, the most serious being those related to the target or features.

Dirty data can undermine the quality of your analyses and models, largely because it distorts conclusions or leads to poor model performance. Datalore's Statistics tab makes it easy to check for these problems by showing at a glance the distribution, the number of missing values and the presence of outliers for each field. Datalore also facilitates the exploration of the raw data and allows to perform basic filtering, sorting and column selection operations directly in a DataFrame, exporting the Python code corresponding to each action to a new cell.

Are the variables balanced?

Unbalanced data occur when categorical fields have an uneven distribution of observations across all classes. This situation can cause significant problems for models and analyses. When you have a very unbalanced target, you can create lazy models that can still achieve good performance by simply predicting the majority class by default. Let's take an extreme example: we have a dataset where 90% of the observations fall into one of the target classes and 10% fall into the other. If we always predicted the majority class for this dataset, we would still get an accuracy of 90%, which shows that, in these cases, a model that learns nothing from the features can perform excellently.

Features are also affected by class imbalance. Models work by learning patterns, and when classes are too small, it is difficult for models to make predictions for these groups. These effects can be exacerbated when you have several unbalanced features, leading to situations where a particular combination of rare classes can only occur in a handful of observations.

Unbalanced data can be rectified by various sampling techniques. Undersampling involves reducing the number of observations in the larger classes to equalise the distribution of the data, and oversampling involves creating more data in the smaller classes. There are many ways to do this. Examples include using Python packages such as imbalanced-learn or services such as Gretel. Unbalanced features can also be corrected by feature engineering, which aims to combine classes within a field without losing information.

In short, is the dataset representative?

When creating a dataset, you have in mind a target group for which you want your model or analysis to work. For example, a model to predict the likelihood that American men interested in fashion will buy a certain brand. This target group is the population you want to be able to make generalisations about. However, as it is often impractical to collect information on all individuals who constitute this part of the population, a subset called a sample is used instead.

Sometimes problems arise that cause the sample data for the machine learning model and analysis to misrepresent the behaviour of the population. This is called data bias. For example, the sample may not capture all subgroups of the population, a type of bias called selection bias.

One way to check for bias is to inspect the distribution of the fields in your data and check that they make sense based on what you know about that population group. Using Datalore's Statistics tab allows you to scan the distribution of continuous and categorical variables in a DataFrame.

Is the actual performance of the models being measured?

A final issue that can put you in a bind is measuring the performance of your models. Many models are prone to a problem called overfitting which is when the model fits the training data so well that it does not generalise well to new data. The telltale sign of overfitting is a model that performs extremely well on training data and underperforms on new data. The way to account for this is to split the dataset into several sets: a training set to train the model, a validation set to compare the performance of different models, and a final test set to check how the model will perform in the real world.

However, creating a clean training-validation-testing split can be tricky. A major problem is data leakage, whereby information from the other two datasets leaks into the training set. This can lead to problems ranging from the obvious, such as duplicate observations ending up in all three datasets, to more subtle ones, such as using information from the entire dataset to perform feature pre-processing before splitting the data. In addition, it is important that the three datasets have the same distribution of targets and features, so that each is a representative sample of the population.

To avoid any problems, you should split the dataset into training, validation and test sets at the beginning of your work, prior to any exploration or processing. To ensure that each dataset has the same distribution of each field, you can use a method such as scikit-learn's train_test_split, which is specifically designed to create representative splits of the data. Finally, it is advisable to compare the descriptive statistics of each dataset to check for signs of data leakage or uneven splits, which is easily done using the Statistics tab in Datalore.

Ultimately, there are a number of issues that can occur when preparing data for machine learning and analytics and it is important to know how to mitigate them. While this can be a time-consuming part of the work process, there are tools that can make it quicker and easier to spot problems at an early stage.

Content drawn from Jodie Burchell's post How to prepare your dataset for machine learning and analysis published in The JetBrains Datalore Blog

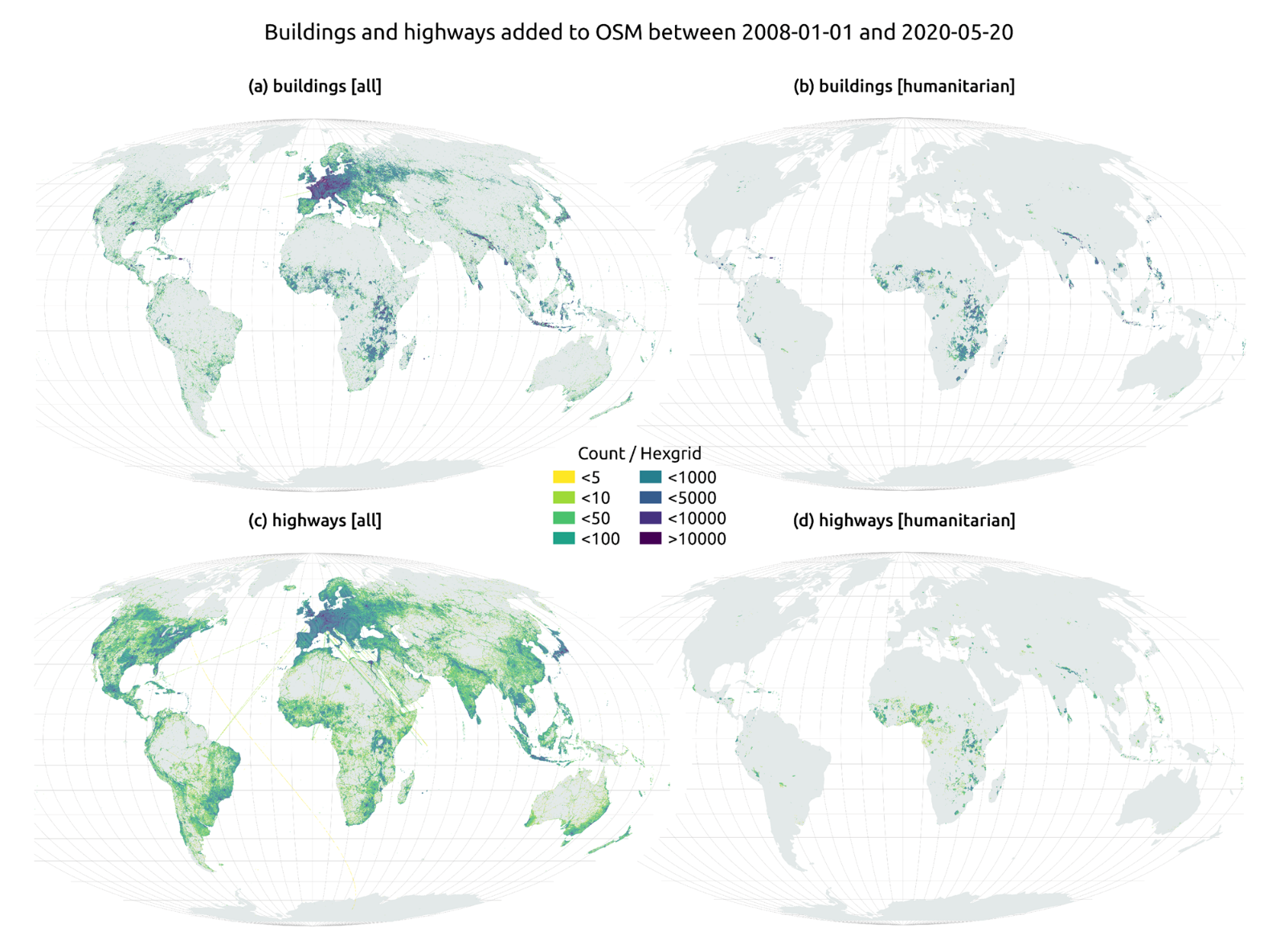

The humanitarian crisis following the earthquake in Haiti in 2010 was the starting point for a voluntary initiative to create maps to identify the level of damage and vulnerability by areas, and thus to coordinate emergency teams. Since then, the collaborative mapping project known as Hot OSM (OpenStreetMap) has played a key role in crisis situations and natural disasters.

Now, the organisation has evolved into a global network of volunteers who contribute their online mapping skills to help in crisis situations around the world. The initiative is an example of data-driven collaboration to solve societal problems, a theme we explore in this data.gob.es report.

Hot OSM works to accelerate data-driven collaboration with humanitarian and governmental organisations, as well as local communities and volunteers around the world, to provide accurate and detailed maps of areas affected by natural disasters or humanitarian crises. These maps are used to help coordinate emergency response, identify needs and plan for recovery.

In its work, Hot OSM prioritises collaboration and empowerment of local communities. The organisation works to ensure that people living in affected areas have a voice and power in the mapping process. This means that Hot OSM works closely with local communities to ensure that areas important to them are mapped. In this way, the needs of communities are considered when planning emergency response and recovery.

Hot OSM's educational work

In addition to its work in crisis situations, Hot OSM is dedicated to promoting access to free and open geospatial data, and works in collaboration with other organisations to build tools and technologies that enable communities around the world to harness the power of collaborative mapping.

Through its online platform, Hot OSM provides free access to a wide range of tools and resources to help volunteers learn and participate in collaborative mapping. The organisation also offers training for those interested in contributing to its work.

One example of a HOT project is the work the organisation carried out in the context of Ebola in West Africa. In 2014, an Ebola outbreak affected several West African countries, including Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea. The lack of accurate and detailed maps in these areas made it difficult to coordinate the emergency response.

In response to this need, HOT initiated a collaborative mapping project involving more than 3,000 volunteers worldwide. Volunteers used online tools to map Ebola-affected areas, including roads, villages and treatment centres.

This mapping allowed humanitarian workers to better coordinate the emergency response, identify high-risk areas and prioritize resource allocation. In addition, the project also helped local communities to better understand the situation and participate in the emergency response.

This case in West Africa is just one example of HOT's work around the world to assist in humanitarian crisis situations. The organisation has worked in a variety of contexts, including earthquakes, floods and armed conflict, and has helped provide accurate and detailed maps for emergency response in each of these contexts.

On the other hand, the platform is also involved in areas where there is no map coverage, such as in many African countries. In these areas, humanitarian aid projects are often very challenging in the early stages, as it is very difficult to quantify what population is living in an area and where they are located. Having the location of these people and showing access routes "puts them on the map" and allows them to gain access to resources.

In this article The evolution of humanitarian mapping within the OpenStreetMap community by Nature, we can see graphically some of the achievements of the platform.

How to collaborate

It is easy to start collaborating with Hot OSM, just go to https://tasks.hotosm.org/explore and see the open projects that need collaboration.

This screen allows us a lot of options when searching for projects, selected by level of difficulty, organisation, location or interests among others.

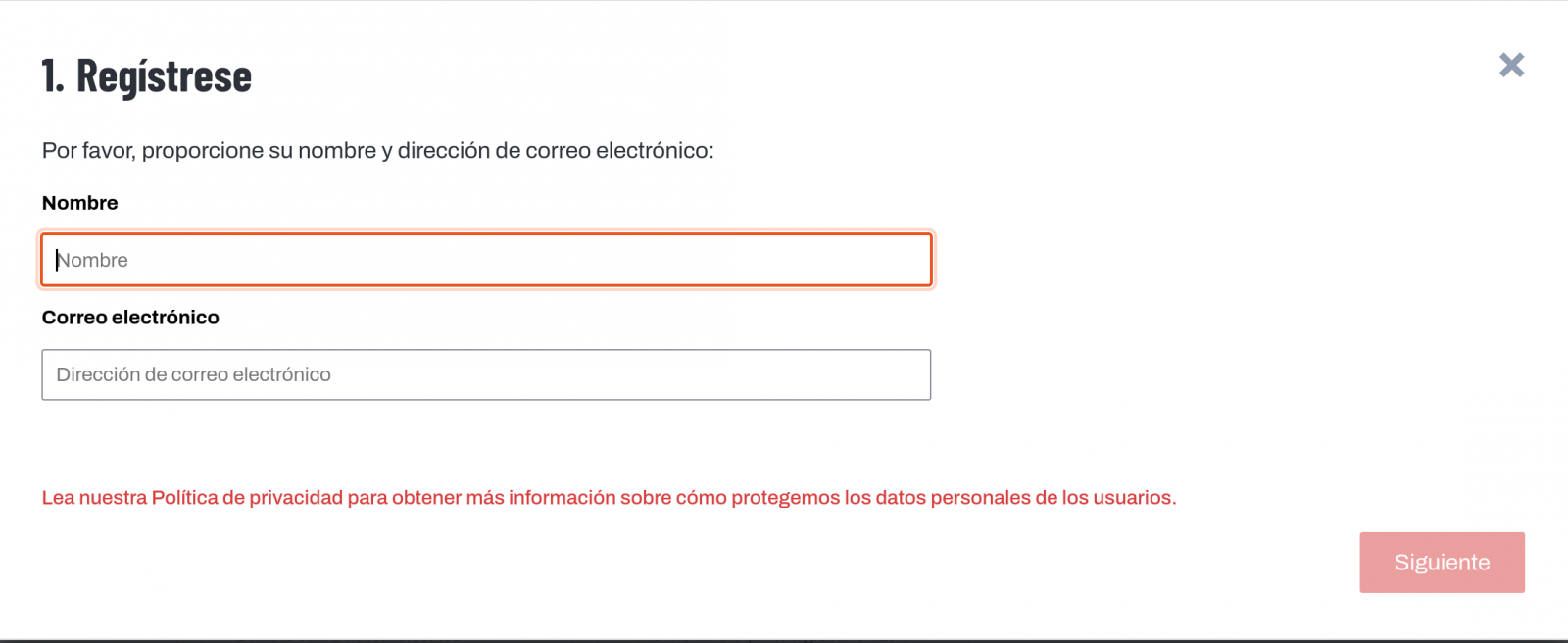

To participate, simply click on the Register button.

Give a name and an e-mail adress on the next screen:

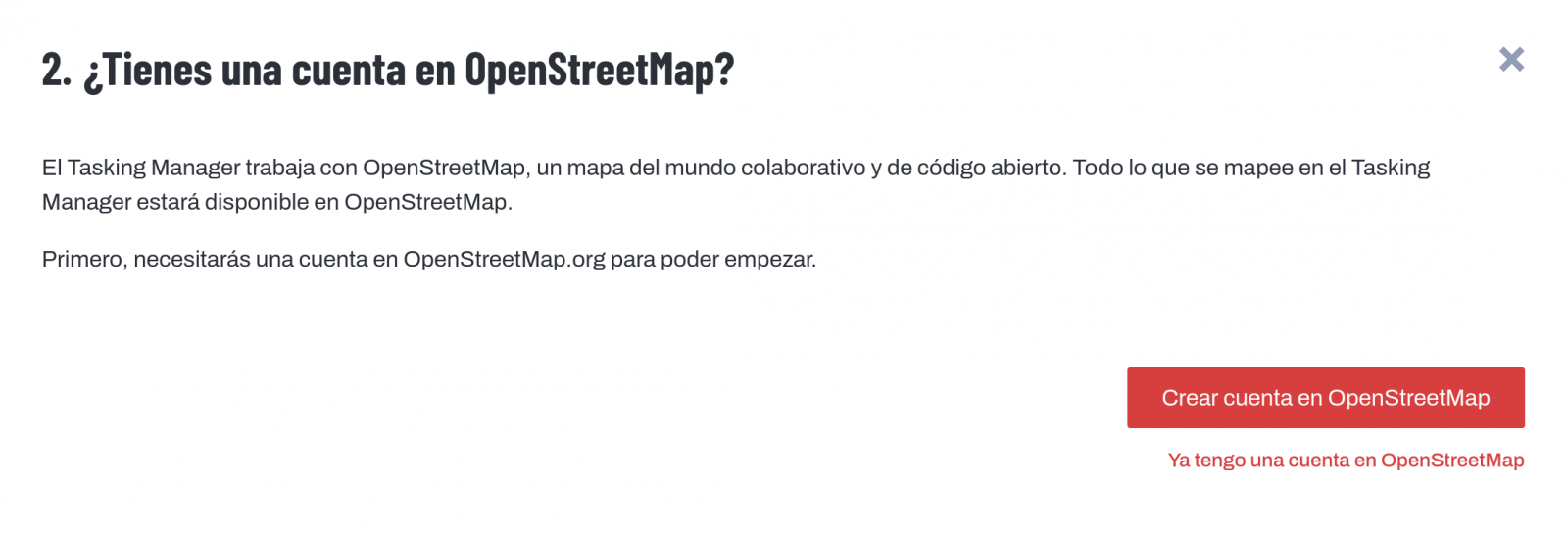

It will ask us if we have already created an account in Open Street Maps or if we want to create one.

If we want to see the process in more detail, this website makes it very easy.

Once the user has been created, on the learning page we find help on how to participate in the project.

It is important to note that the contributions of the volunteers are reviewed and validated and there is a second level of volunteers, the validators, who validate the work of the beginners. During the development of the tool, the HOT team has taken great care to make it a user-friendly application so as not to limit its use to people with computer skills.

In addition, organisations such as the Red Cross and the United Nations regularly organise mapathons to bring together groups of people for specific projects or to teach new volunteers how to use the tool. These meetings serve, above all, to remove the new users' fear of "breaking something" and to allow them to see how their voluntary work serves concrete purposes and helps other people.

Another of the project's great strengths is that it is based on free software and allows for its reuse. In the MissingMaps project's Github repository we can find the code and if we want to create a community based on the software, the Missing Maps organisation facilitates the process and gives visibility to our group.

In short, Hot OSM is a citizen science and data altruism project that contributes to bringing benefits to society through the development of collaborative maps that are very useful in emergency situations. This type of initiative is aligned with the European concept of data governance that seeks to encourage altruism to voluntarily facilitate the use of data for the common good.

Content by Santiago Mota, senior data scientist.

The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.