Language models are at the epicentre of the technological paradigm shift that has been taking place in generative artificial intelligence (AI) over the last two years. From the tools with which we interact in natural language to generate text, images or videos and which we use to create creative content, design prototypes or produce educational material, to more complex applications in research and development that have even been instrumental in winning the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, language models are proving their usefulness in a wide variety of applicationsthat we are still exploring.

Since Google's influential 2017 paper "Attention is all you need" describing the architecture of the Transformers, the technology underpinning the new capabilities that OpenAI popularised in late 2022 with the launch of ChatGPT, the evolution of language models has been more than dizzying. In just two years, we have moved from models focused solely on text generation to multimodal versions that integrate interaction and generation of text, images and audio.

This rapid evolution has given rise to two categories of language models: SLMs (Small Language Models), which are lighter and more efficient, and LLLMs (Large Language Models), which are heavier and more powerful. Far from considering them as competitors, we should analyse SLM and LLM as complementary technologies. While LLLMs offer general processing and content generation capabilities, SLMs can provide support for more agile and specialised solutions for specific needs. However, both share one essential element: they rely on large volumes of data for training and at the heart of their capabilities is open data, which is part of the fuel used to train these language models on which generative AI applications are based.

LLLM: power driven by massive data

The LLLMs are large-scale language models with billions, even trillions, of parameters. These parameters are the mathematical units that allow the model to identify and learn patterns in the training data, giving them an extraordinary ability to generate text (or other formats) that is consistent and adapted to the users' context. These models, such as the GPT family from OpenAI, Gemini from Google or Llama from Meta, are trained on immense volumes of data and are capable of performing complex tasks, some even for which they were not explicitly trained.

Thus, LLMs are able to perform tasks such as generating original content, answering questions with relevant and well-structured information or generating software code, all with a level of competence equal to or higher than humans specialised in these tasks and always maintaining complex and fluent conversations.

The LLLMs rely on massive amounts of data to achieve their current level of performance: from repositories such as Common Crawl, which collects data from millions of web pages, to structured sources such as Wikipedia or specialised sets such as PubMed Open Access in the biomedical field. Without access to these massive bodies of open data, the ability of these models to generalise and adapt to multiple tasks would be much more limited.

However, as LLMs continue to evolve, the need for open data increases to achieve specific advances such as:

- Increased linguistic and cultural diversity: although today's LLMs are multilingual, they are generally dominated by data in English and other major languages. The lack of open data in other languages limits the ability of these models to be truly inclusive and diverse. More open data in diverse languages would ensure that LLMs can be useful to all communities, while preserving the world's cultural and linguistic richness.

- Reducción de sesgos: los LLM, como cualquier modelo de IA, son propensos a reflejar los sesgos presentes en los datos con los que se entrenan. This sometimes leads to responses that perpetuate stereotypes or inequalities. Incorporating more carefully selected open data, especially from sources that promote diversity and equality, is fundamental to building models that fairly and equitably represent different social groups.

- Constant updating: Data on the web and other open resources is constantly changing. Without access to up-to-date data, the LLMs generate outdated responses very quickly. Therefore, increasing the availability of fresh and relevant open data would allow LLMs to keep in line with current events[9].

- Entrenamiento más accesible: a medida que los LLM crecen en tamaño y capacidad, también lo hace el coste de entrenarlos y afinarlos. Open data allows independent developers, universities and small businesses to train and refine their own models without the need for costly data acquisitions. This democratises access to artificial intelligence and fosters global innovation.

To address some of these challenges, the new Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2024 includes measures aimed at generating models and corpora in Spanish and co-official languages, including the development of evaluation datasets that consider ethical evaluation.

SLM: optimised efficiency with specific data

On the other hand, SLMs have emerged as an efficient and specialised alternative that uses a smaller number of parameters (usually in the millions) and are designed to be lightweight and fast. Aunque no alcanzan la versatilidad y competencia de los LLM en tareas complejas, los SLM destacan por su eficiencia computacional, rapidez de implementación y capacidad para especializarse en dominios concretos.

For this, SLMs also rely on open data, but in this case, the quality and relevance of the datasets are more important than their volume, so the challenges they face are more related to data cleaning and specialisation. These models require sets that are carefully selected and tailored to the specific domain for which they are to be used, as any errors, biases or unrepresentativeness in the data can have a much greater impact on their performance. Moreover, due to their focus on specialised tasks, the SLMs face additional challenges related to the accessibility of open data in specific fields. For example, in sectors such as medicine, engineering or law, relevant open data is often protected by legal and/or ethical restrictions, making it difficult to use it to train language models.

The SLMs are trained with carefully selected data aligned to the domain in which they will be used, allowing them to outperform LLMs in accuracy and specificity on specific tasks, such as for example:

- Text autocompletion: a SLM for Spanish autocompletion can be trained with a selection of books, educational texts or corpora such as those to be promoted in the aforementioned AI Strategy, being much more efficient than a general-purpose LLM for this task.

- Legal consultations: a SLM trained with open legal datasets can provide accurate and contextualised answers to legal questions or process contractual documents more efficiently than a LLM.

- Customised education: ein the education sector, SLM trained with open data teaching resources can generate specific explanations, personalised exercises or even automatic assessments, adapted to the level and needs of the student.

- Medical diagnosis: An SLM trained with medical datasets, such as clinical summaries or open publications, can assist physicians in tasks such as identifying preliminary diagnoses, interpreting medical images through textual descriptions or analysing clinical studies.

Ethical Challenges and Considerations

We should not forget that, despite the benefits, the use of open data in language modelling presents significant challenges. One of the main challenges is, as we have already mentioned, to ensure the quality and neutrality of the data so that they are free of biases, as these can be amplified in the models, perpetuating inequalities or prejudices.

Even if a dataset is technically open, its use in artificial intelligence models always raises some ethical implications. For example, it is necessary to avoid that personal or sensitive information is leaked or can be deduced from the results generated by the models, as this could cause damage to the privacy of individuals.

The issue of data attribution and intellectual property must also be taken into account. The use of open data in business models must address how the original creators of the data are recognised and adequately compensated so that incentives for creators continue to exist.

Open data is the engine that drives the amazing capabilities of language models, both SLM and LLM. While the SLMs stand out for their efficiency and accessibility, the LLMs open doors to advanced applications that not long ago seemed impossible. However, the path towards developing more capable, but also more sustainable and representative models depends to a large extent on how we manage and exploit open data.

Contenido elaborado por Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization. Los contenidos y los puntos de vista reflejados en esta publicación son responsabilidad exclusiva de su autor.

The 2024 Best Cases Awards of the Public Sector Tech Watch observatory now have finalists. These awards seek to highlight solutions that use emerging technologies, such as artificial intelligence or blockchain, in public administrations, through two categories:

- Solutions to improve the public services offered to citizens (Government-to-Citizen or G2C).

- Solutions to improve the internal processes of the administrations themselves (Government-to-Government or G2G).

The awards are intended to create a mechanism for sharing the best experiences on the use of emerging technologies in the public sector and thus give visibility to the most innovative administrations in Europe.

Almost 60% of the finalist solutions are Spanish.

In total, 32 proposals have been received, 14 of which have been pre-selected in a preliminary evaluation. Of these, more than half are solutions from Spanish organisations. Specifically, nine finalists have been shortlisted for the G2G category -five of them Spanish- and five for G2C -three of them linked to our country-.The following is a summary of what these Spanish solutions consist of.

Solutions to improve the internal processes of the administrations themselves.

- Innovation in local government: digital transformation and GeoAI for data management (Alicante Provincial Council).

Suma Gestión Tributaria, of the Diputación de Alicante, is the agency in charge of managing and collecting the municipal taxes of the city councils of its province. To optimise this task, they have developed a solution that combines geographic information systems and artificial intelligence (machine learning and deep learning) to improve training in detection of properties that do not pay taxes. This solution collects data from multiple administrations and entities in order to avoid delays in the collection of municipalities.

- Regional inspector of public infrastructures: monitoring of construction sites (Provincial Council of Bizkaia and Interbiak).

The autonomous road inspector and autonomous urban inspector help public administrations to automatically monitor roads. These solutions, which can be installed in any vehicle, use artificial or computer vision techniques along with information from sensors to automatically check the condition of traffic signs, road markings, protective barriers, etc. They also perform early forecasting of pavement degradation, monitor construction sites and generate alerts for hazards such as possible landslides.

- Application of drones for the transport of biological samples (Centre for Telecommunications and Information Technologies -CTTI-, Generalitat de Catalunya).

This pilot project implements and evaluates a health transport route in the Girona health region. Its aim is to transport biological samples (blood and urine) between a primary health centre and a hospital using drones. As a result, the journey time has been reduced from 20 minutes with ground transport to seven minutes with the use of drones. This has improved the quality of the samples transported, increased flexibility in scheduling transport times and reduced environmental impact.

- Robotic automation of processes in the administration of justice (Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts).

Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts has implemented a solution for the robotisation of administrative processes in order to streamline routine, repetitive and low-risk work. To date, more than 25 process automation lines have been implemented, including the automatic cancellation of criminal records, nationality applications, automatic issuance of life insurance certificates, etc. As a result, it is estimated that more than 500,000 working hourshave been saved.

- Artificial intelligence in the processing of official publications (Official Gazette of the Province of Barcelona and Official Documentation and Publications Service, Barcelona Provincial Council).

CIDO (Official Information and Documentation Search Engine) has implemented an AI system that automatically generates summaries of official publications of the public administrations of Barcelona. Using supervised machine learning and neural networkstechniques, the system generates summaries of up to 100 words for publications in Catalan or Spanish. The tool allows the recording of manual modifications to improve accuracy.

Solutions to improve the public services offered to citizens

- Virtual Desk of Digital Immediacy: bringing Justice closer to citizens through digitalisation (Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts).

The Virtual Digital Immediacy Desktop (EVID) allows remote hearings with full guarantees of legal certainty using blockchain technologies. The solution integrates the convening of the hearing, the provision of documentation, the identification of the participants, the acceptance of consents, the generation of the document justifying the action carried out, the signing of the document and the recording of the session. In this way, legal acts can be carried out from anywhere, without the need to travel and in a simple way, making justice more inclusive, accessible and environmentally friendly. By the end of June 2024, more than 370,000 virtual sessions had been held through EVID.

- Application of Generative AI to make it easier for citizens to understand legal texts (Entitat Autònoma del Diari Oficial i Publicacions -EADOP-, Generalitat de Catalunya).

Legal language is often a barrier that prevents citizens from easily understanding legal texts. To remove this obstacle, the Government is making available to users of the Legal Portal of Catalonia and to the general public the summaries of Catalan law in simple language obtained from generative artificial intelligence. The aim is to have summaries of the more than 14,000 14,000 existing regulatory provisions adapted to clear communication available by the end of the year. The abstracts will be published in Catalan and Spanish, with the prospect of also offering a version in Aranesein the future.

- Emi - Intelligent Employment (Consellería de Emprego, Comercio e Emigración de la Xunta de Galicia).

Emi, Intelligent Employment is an artificial intelligence and big data tool that helps the offices of the Public Employment Service of Galicia to orient unemployed people towards the skills required by the labour market, according to their abilities. AI models make six-month projections of contracts for a particular occupation for a chosen geographical area. In addition, they allow estimating the probability of finding employment for individuals in the coming months.

You can see all the solutions presented here. The winners will be announced at the final event on 28 November. The ceremony takes place in Brussels, but can also be followed online. To do so, you need to register here.

Public Sector Tech Watch: an observatory to inspire new projects

Public Sector Tech Watch (PSTW), managed by the European Commission, is positioned as a "one-stop shop" for all those interested - public sector, policy makers, private companies, academia, etc. - in the latest technological developments to improve public sector performance and service delivery. For this purpose, it has several sections where the following information of interest is displayed:

- Cases: contains examples of how innovative technologies and their associated data are used by public sector organisations in Europe.

- Stories: presents testimonials to show the challenges faced by European administrations in implementing technological solutions.

If you know of a case of interest that is not currently monitored by PSTW, you can register it here. Successful cases are reviewed and evaluated before being included in the database.

From October 28 to November 24, registration will be open for submitting proposals to the challenge organized by the Diputación de Bizkaia. The goal of the competition is to identify initiatives that combine the reuse of available data from the Open Data Bizkaia portal with the use of artificial intelligence. The complete guidelines are available at this link, but in this post, we will cover everything you need to know about this contest, which offers cash prizes for the five best projects.

Participants must use at least one dataset from the Diputación Foral de Bizkaia or from the municipalities in the territory, which can be found in the catalog, to address one of the five proposed use cases:

-

Promotional content about tourist attractions in Bizkaia: Written promotional content, such as generated images, flyers, etc., using datasets like:

- Beaches of Bizkaia by municipality

- Cultural agenda – BizkaiKOA

- Cultural agenda of Bizkaia

- Bizkaibus

- Trails

- Recreation areas

- Hotels in Euskadi – Open Data Euskadi

- Temperature predictions in Bizkaia – Weather API data

-

Boosting tourism through sentiment analysis: Text files with recommendations for improving tourist resources, such as Excel and PowerPoint reports, using datasets like:

- Beaches of Bizkaia by municipality

- Cultural agenda – BizkaiKOA

- Cultural agenda of Bizkaia

- Bizkaibus

- Trails

- Recreation areas

- Hotels in Euskadi – Open Data Euskadi

- Google reviews API – this resource is paid with a possible free tier

-

Personalized tourism guides: Chatbot or document with personalized recommendations using datasets like:

- Tide table 2024

- Beaches of Bizkaia by municipality

- Cultural agenda – BizkaiKOA

- Cultural agenda of Bizkaia

- Bizkaibus

- Trails

- Hotels in Euskadi – Open Data Euskadi

- Temperature predictions in Bizkaia – Weather API data, resource with a free tier

-

Personalized cultural event recommendations: Chatbot or document with personalized recommendations using datasets like:

- Cultural agenda – BizkaiKOA

- Cultural agenda of Bizkaia

-

Waste management optimization: Excel, PowerPoint, and Word reports containing recommendations and strategies using datasets like:

- Urban waste

- Containers by municipality

How to participate?

Participants can register individually or in teams via this form available on the website. The registration period is from October 28 to November 24, 2024. Once registration closes, teams must submit their solutions on Sharepoint. A jury will pre-select five finalists, who will have the opportunity to present their project at the final event on December 12, where the prizes will be awarded. The organization recommends attending in person, but online attendance will also be allowed if necessary.

The competition is open to anyone over 16 years old with a valid ID or passport, who is not affiliated with the organizing entities. Additionally, multiple proposals can be submitted.

What are the prizes?

The jury members will select five winning projects based on the following evaluation criteria:

- Suitability of the proposed solution to the selected challenge.

- Creativity and innovation.

- Quality and coherence of the solution.

- Suitability of the Open Data Bizkaia datasets used.

The winning candidates will receive a cash prize, as well as the commitment to open the datasets associated with the project, to the extent possible.

- First prize: €2,000.

- Second prize: €1,000.

- Three prizes for the remaining finalists of €500 each.

One of the objectives of this challenge, as explained by the Diputación Foral de Bizkaia, is to understand whether the current dataset offerings meet demand. Therefore, if any participant requires a dataset from Bizkaia or its municipalities that is not available, they can propose that the institution make it publicly available, as long as the information falls within the competencies of the Diputación Foral de Bizkaia or the municipalities.

This is a unique event that will not only allow you to showcase your skills in artificial intelligence and open data but also contribute to the development and improvement of Bizkaia. Don’t miss the chance to be part of this exciting challenge. Sign up and start creating innovative solutions!

Natural language processing (NLP) is a branch of artificial intelligence that allows machines to understand and manipulate human language. At the core of many modern applications, such as virtual assistants, machine translation and chatbots, are word embeddings. But what exactly are they and why are they so important?

What are word embeddings?

Word embeddings are a technique that allows machines to represent the meaning of words in such a way that complex relationships between words can be captured. To understand this, let's think about how words are used in a given context: a word acquires meaning depending on the words surrounding it. For example, the word bank can refer to a financial institution or to a headquarters, depending on the context in which it is found.

To visualise this, imagine that words like lake, river and ocean would be close together in this space, while words like lake and building would be much further apart. This structure enables language processing algorithms to perform complex tasks, such as finding synonyms, making accurate translations or even answering context-based questions.

How are word embeddings created?

The main objective of word embeddings is to capture semantic relationships and contextual information of words, transforming them into numerical representations that can be understood by machine learning algorithms. Instead of working with raw text, machines require words to be converted into numbers in order to identify patterns and relationships effectively.

The process of creating word embeddings consists of training a model on a large corpus of text, such as Wikipedia articles or news items, to learn the structure of the language. The first step involves performing a series of pre-processing on the corpus, which includes tokenise the words, removing punctuation and irrelevant terms, and, in some cases, converting the entire text to lower case to maintain consistency.

The use of context to capture meaning

Once the text has been pre-processed, a technique known as "sliding context window" is used to extract information. This means that, for each target word, the surrounding words within a certain range are taken into account. For example, if the context window is 3 words, for the word airplane in the sentence "The plane takes off at six o'clock", the context words will be The, takes off, to.

The model is trained to learn to predict a target word using the words in its context (or conversely, to predict the context from the target word). To do this, the algorithm adjusts its parameters so that the vectors assigned to each word are closer in vector space if those words appear frequently in similar contexts.

How models learn language structure

The creation of word embeddings is based on the ability of these models to identify patterns and semantic relationships. During training, the model adjusts the values of the vectors so that words that often share contexts have similar representations. For example, if airplane and helicopter are frequently used in similar phrases (e.g. in the context of air transport), the vectors of airplane and helicopter will be close together in vector space.

As the model processes more and more examples of sentences, it refines the positions of the vectors in the continuous space. Thus, the vectors reflect not only semantic proximity, but also other relationships such as synonyms, categories (e.g., fruits, animals) and hierarchical relationships (e.g., dog and animal).

A simplified example

Imagine a small corpus of only six words: guitar, bass, drums, piano, car and bicycle. Suppose that each word is represented in a three-dimensional vector space as follows:

guitar [0.3, 0.8, -0.1]

bass [0.4, 0.7, -0.2]

drums [0.2, 0.9, -0.1]

piano [0.1, 0.6, -0.3]

car [0.8, -0.1, 0.6]

bicycle [0.7, -0.2, 0.5]

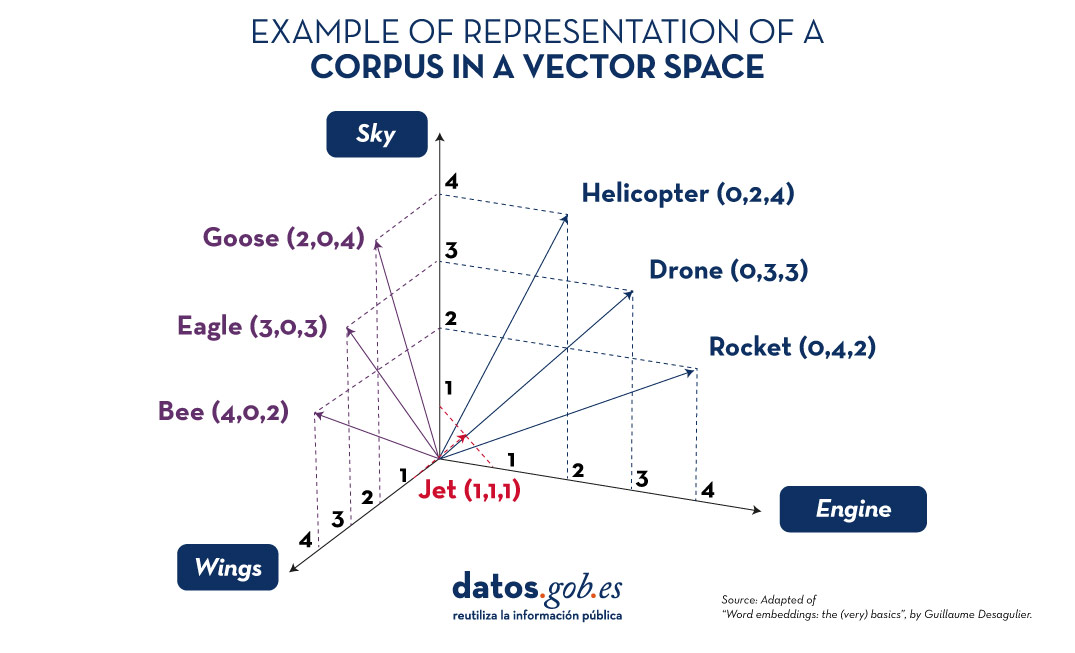

In this simplified example, the words guitar, bass, drums and piano represent musical instruments and are located close to each other in vector space, as they are used in similar contexts. In contrast, car and bicycle, which belong to the category of means of transport, are distant from musical instruments but close to each other. This other image shows how different terms related to sky, wings and engineering would look like in a vector space.

Figure 1. Examples of representation of a corpus in a vector space. Source: Adapted from “Word embeddings: the (very) basics”, by Guillaume Desagulier.

This example only uses three dimensions to illustrate the idea, but in practice, word embeddings usually have between 100 and 300 dimensions to capture more complex semantic relationships and linguistic nuances.

The result is a set of vectors that efficiently represent each word, allowing language processing models to identify patterns and semantic relationships more accurately. With these vectors, machines can perform advanced tasks such as semantic search, text classification and question answering, significantly improving natural language understanding.

Strategies for generating word embeddings

Over the years, multiple approaches and techniques have been developed to generate word embeddings. Each strategy has its own way of capturing the meaning and semantic relationships of words, resulting in different characteristics and uses. Some of the main strategies are presented below:

1. Word2Vec: local context capture

Developed by Google, Word2Vec is one of the most popular approaches and is based on the idea that the meaning of a word is defined by its context. It uses two main approaches:

- CBOW (Continuous Bag of Words): In this approach, the model predicts the target word using the words in its immediate environment. For example, given a context such as "The dog is ___ in the garden", the model attempts to predict the word playing, based on the words The, dog, is and garden.

- Skip-gram: Conversely, Skip-gram uses a target word to predict the surrounding words. Using the same example, if the target word is playing, the model would try to predict that the words in its environment are The, dog, is and garden.

The key idea is that Word2Vec trains the model to capture semantic proximity across many iterations on a large corpus of text. Words that tend to appear together have closer vectors, while unrelated words appear further apart.

2. GloVe: global statistics-based approach

GloVe, developed at Stanford University, differs from Word2Vec by using global co-occurrence statistics of words in a corpus. Instead of considering only the immediate context, GloVe is based on the frequency with which two words appear together in the whole corpus.

For example, if bread and butter appear together frequently, but bread and planet are rarely found in the same context, the model adjusts the vectors so that bread and butter are close together in vector space.

This allows GloVe to capture broader global relationships between words and to make the representations more robust at the semantic level. Models trained with GloVe tend to perform well on analogy and word similarity tasks.

3. FastText: subword capture

FastText, developed by Facebook, improves on Word2Vec by introducing the idea of breaking down words into sub-words. Instead of treating each word as an indivisible unit, FastText represents each word as a sum of n-grams. For example, the word playing could be broken down into play, ayi, ing, and so on.

This allows FastText to capture similarities even between words that did not appear explicitly in the training corpus, such as morphological variations (playing, play, player). This is particularly useful for languages with many grammatical variations.

4. Embeddings contextuales: dynamic sense-making

Models such as BERT and ELMo represent a significant advance in word embeddings. Unlike the previous strategies, which generate a single vector for each word regardless of the context, contextual embeddings generate different vectors for the same word depending on its use in the sentence.

For example, the word bank will have a different vector in the sentence "I sat on the park bench" than in "the bank approved my credit application". This variability is achieved by training the model on large text corpora in a bidirectional manner, i.e. considering not only the words preceding the target word, but also those following it.

Practical applications of word embeddings

ord embeddings are used in a variety of natural language processing applications, including:

- Named Entity Recognition (NER): allows you to identify and classify names of people, organisations and places in a text. For example, in the sentence "Apple announced its new headquarters in Cupertino", the word embeddings allow the model to understand that Apple is an organisation and Cupertino is a place.

- Automatic translation: helps to represent words in a language-independent way. By training a model with texts in different languages, representations can be generated that capture the underlying meaning of words, facilitating the translation of complete sentences with a higher level of semantic accuracy.

- Information retrieval systems: in search engines and recommender systems, word embeddings improve the match between user queries and relevant documents. By capturing semantic similarities, they allow even non-exact queries to be matched with useful results. For example, if a user searches for "medicine for headache", the system can suggest results related to analgesics thanks to the similarities captured in the vectors.

- Q&A systems: word embeddings are essential in systems such as chatbots and virtual assistants, where they help to understand the intent behind questions and find relevant answers. For example, for the question "What is the capital of Italy?", the word embeddings allow the system to understand the relationship between capital and Italy and find Rome as an answer.

- Sentiment analysis: word embeddings are used in models that determine whether the sentiment expressed in a text is positive, negative or neutral. By analysing the relationships between words in different contexts, the model can identify patterns of use that indicate certain feelings, such as joy, sadness or anger.

- Semantic clustering and similarity detection: word embeddings also allow you to measure the semantic similarity between documents, phrases or words. This is used for tasks such as grouping related items, recommending products based on text descriptions or even detecting duplicates and similar content in large databases.

Conclusion

Word embeddings have transformed the field of natural language processing by providing dense and meaningful representations of words, capable of capturing their semantic and contextual relationships. With the emergence of contextual embeddings , the potential of these representations continues to grow, allowing machines to understand even the subtleties and ambiguities of human language. From applications in translation and search systems, to chatbots and sentiment analysis, word embeddings will continue to be a fundamental tool for the development of increasingly advanced and humanised natural language technologies.

Content prepared by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies linked to the data economy. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

On 11, 12 and 13 November, a new edition of DATAforum Justice will be held in Granada. The event will bring together more than 100 speakers to discuss issues related to digital justice systems, artificial intelligence (AI) and the use of data in the judicial ecosystem.The event is organized by the Ministry of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Courts, with the collaboration of the University of Granada, the Andalusian Regional Government, the Granada City Council and the Granada Training and Management entity.

The following is a summary of some of the most important aspects of the conference.

An event aimed at a wide audience

This annual forum is aimed at both public and private sector professionals, without neglecting the general public, who want to know more about the digital transformation of justice in our country.

The DATAforum Justice 2024 also has a specific itinerary aimed at students, which aims to provide young people with valuable tools and knowledge in the field of justice and technology. To this end, specific presentations will be given and a DATAthon will be set up. These activities are particularly aimed at students of law, social sciences in general, computer engineering or subjects related to digital transformation. Attendees can obtain up to 2 ECTS credits (European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System): one for attending the conference and one for participating in the DATAthon.

Data at the top of the agenda

The Paraninfo of the University of Granada will host experts from the administration, institutions and private companies, who will share their experience with an emphasis on new trends in the sector, the challenges ahead and the opportunities for improvement.

The conference will begin on Monday 11 November at 9:00 a.m., with a welcome to the students and a presentation of DATAthon. The official inauguration, addressed to all audiences, will be at 11:35 a.m. and will be given by Manuel Olmedo Palacios, Secretary of State for Justice, and Pedro Mercado Pacheco, Rector of the University of Granada.

From then on, various talks, debates, interviews, round tables and conferences will take place, including a large number of data-related topics. Among other issues, the data management, both in administrations and in companies, will be discussed in depth. It will also address the use of open data to prevent everything from hoaxes to suicide and sexual violence.

Another major theme will be the possibilities of artificial intelligence for optimising the sector, touching on aspects such as the automation of justice, the making of predictions. It will include presentations of specific use cases, such as the use of AI for the identification of deceased persons, without neglecting issues such as the governance of algorithms.

The event will end on Wednesday 13 at 17:00 hours with the official closing ceremony. On this occasion, Félix Bolaños, Minister of the Presidency, Justice and Relations with the Cortes, will accompany the Rector of the University of Granada.

A Datathon to solve industry challenges through data

In parallel to this agenda, a DATAthon will be held in which participants will present innovative ideas and projects to improve justice in our society. It is a contest aimed at students, legal and IT professionals, research groups and startups.

Participants will be divided into multidisciplinary teams to propose solutions to a series of challenges, posed by the organisation, using data science oriented technologies. During the first two days, participants will have time to research and develop their original solution. On the third day, they will have to present a proposal to a qualified jury. The prizes will be awarded on the last day, before the closing ceremony and the Spanish wine and concert that will bring the 2024 edition of DATAfórum Justicia to a close.

In the 2023 edition, 35 people participated, divided into 6 teams that solved two case studies with public data and two prizes of 1,000 euros were awarded.

How to register

The registration period for the DATAforum Justice 2024 is now open. This must be done through the event website, indicating whether it is for the general public, public administration staff, private sector professionals or the media.

To participate in the DATAthon it is necessary to register also on the contest site.

Last year's edition, focusing on proposals to increase efficiency and transparency in judicial systems, was a great success, with over 800 registrants. This year again, a large number of people are expected, so we encourage you to book your place as soon as possible. This is a great opportunity to learn first-hand about successful experiences and to exchange views with experts in the sector.

A digital twin is a virtual, interactive representation of a real-world object, system or process. We are talking, for example, about a digital replica of a factory, a city or even a human body. These virtual models allow simulating, analysing and predicting the behaviour of the original element, which is key for optimisation and maintenance in real time.

Due to their functionalities, digital twins are being used in various sectors such as health, transport or agriculture. In this article, we review the benefits of their use and show two examples related to open data.

Advantages of digital twins

Digital twins use real data sources from the environment, obtained through sensors and open platforms, among others. As a result, the digital twins are updated in real time to reflect reality, which brings a number of advantages:

- Increased performance: one of the main differences with traditional simulations is that digital twins use real-time data for modelling, allowing better decisions to be made to optimise equipment and system performance according to the needs of the moment.

- Improved planning: using technologies based on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, the digital twin can analyse performance issues or perform virtual "what-if" simulations. In this way, failures and problems can be predicted before they occur, enabling proactive maintenance.

- Cost reduction: improved data management thanks to a digital twin generates benefits equivalent to 25% of total infrastructure expenditure. In addition, by avoiding costly failures and optimizing processes, operating costs can be significantly reduced. They also enable remote monitoring and control of systems from anywhere, improving efficiency by centralizing operations.

- Customization and flexibility: by creating detailed virtual models of products or processes, organizations can quickly adapt their operations to meet changing environmental demands and individual customer/citizen preferences. For example, in manufacturing, digital twins enable customized mass production, adjusting production lines in real time to create unique products according to customer specifications. On the other hand, in healthcare, digital twins can model the human body to customize medical treatments, thereby improving efficacy and reducing side effects.

- Boosting experimentation and innovation: digital twins provide a safe and controlled environment for testing new ideas and solutions, without the risks and costs associated with physical experiments. Among other issues, they allow experimentation with large objects or projects that, due to their size, do not usually lend themselves to real-life experimentation.

- Improved sustainability: by enabling simulation and detailed analysis of processes and systems, organizations can identify areas of inefficiency and waste, thus optimizing the use of resources. For example, digital twins can model energy consumption and production in real time, enabling precise adjustments that reduce consumption and carbon emissions.

Examples of digital twins in Spain

The following three examples illustrate these advantages.

GeDIA project: artificial intelligence to predict changes in territories

GeDIA is a tool for strategic planning of smart cities, which allows scenario simulations. It uses artificial intelligence models based on existing data sources and tools in the territory.

The scope of the tool is very broad, but its creators highlight two use cases:

- Future infrastructure needs: the platform performs detailed analyses considering trends, thanks to artificial intelligence models. In this way, growth projections can be made and the needs for infrastructures and services, such as energy and water, can be planned in specific areas of a territory, guaranteeing their availability.

- Growth and tourism: GeDIA is also used to study and analyse urban and tourism growth in specific areas. The tool identifies patterns of gentrification and assesses their impact on the local population, using census data. In this way, demographic changes and their impact, such as housing needs, can be better understood and decisions can be made to facilitate equitable and sustainable growth.

This initiative has the participation of various companies and the University of Malaga (UMA), as well as the financial backing of Red.es and the European Union.

Digital twin of the Mar Menor: data to protect the environment

The Mar Menor, the salt lagoon of the Region of Murcia, has suffered serious ecological problems in recent years, influenced by agricultural pressure, tourism and urbanisation.

To better understand the causes and assess possible solutions, TRAGSATEC, a state-owned environmental protection agency, developed a digital twin. It mapped a surrounding area of more than 1,600 square kilometres, known as the Campo de Cartagena Region. In total, 51,000 nadir images, 200,000 oblique images and more than four terabytes of LiDAR data were obtained.

Thanks to this digital twin, TRAGSATEC has been able to simulate various flooding scenarios and the impact of installing containment elements or obstacles, such as a wall, to redirect the flow of water. They have also been able to study the distance between the soil and the groundwater, to determine the impact of fertiliser seepage, among other issues.

Challenges and the way forward

These are just two examples, but they highlight the potential of an increasingly popular technology. However, for its implementation to be even greater, some challenges need to be addressed, such as initial costs, both in technology and training, or security, by increasing the attack surface. Another challenge is the interoperability problems that arise when different public administrations establish digital twins and local data spaces. To address this issue further, the European Commission has published a guide that helps to identify the main organisational and cultural challenges to interoperability, offering good practices to overcome them.

In short, digital twins offer numerous advantages, such as improved performance or cost reduction. These benefits are driving their adoption in various industries and it is likely that, as current challenges are overcome, digital twins will become an essential tool for optimising processes and improving operational efficiency in an increasingly digitised world.

Almost half of European adults lack basic digital skills. According to the latest State of the Digital Decade report, in 2023, only 55.6% of citizens reported having such skills. This percentage rises to 66.2% in the case of Spain, ahead of the European average.

Having basic digital skills is essential in today's society because it enables access to a wider range of information and services, as well as effective communication in onlineenvironments, facilitating greater participation in civic and social activities. It is also a great competitive advantage in the world of work.

In Europe, more than 90% of professional roles require a basic level of digital skills. Technological knowledge has long since ceased to be required only for technical professions, but is spreading to all sectors, from business to transport and even agriculture. In this respect, more than 70% of companies said that the lack of staff with the right digital skills is a barrier to investment.

A key objective of the Digital Decade is therefore to ensure that at least 80% of people aged 16-74 have at least basic digital skills by 2030.

Basic technology skills that everyone should have

When we talk about basic technological capabilities, we refer, according to the DigComp framework , to a number of areas, including:

- Information and data literacy: includes locating, retrieving, managing and organising data, judging the relevance of the source and its content.

- Communication and collaboration: involves interacting, communicating and collaborating through digital technologies taking into account cultural and generational diversity. It also includes managing one's own digital presence, identity and reputation.

- Digital content creation: this would be defined as the enhancement and integration of information and content to generate new messages, respecting copyrights and licences. It also involves knowing how to give understandable instructions to a computer system.

- Security: this is limited to the protection of devices, content, personal data and privacy in digital environments, to protect physical and mental health.

- Problem solving: it allows to identify and solve needs and problems in digital environments. It also focuses on the use of digital tools to innovate processes and products, keeping up with digital evolution.

Which data-related jobs are most in demand?

Now that the core competences are clear, it is worth noting that in a world where digitalisation is becoming increasingly important , it is not surprising that the demand for advanced technological and data-related skills is also growing.

According to data from the LinkedIn employment platform, among the 25 fastest growing professions in Spain in 2024 are security analysts (position 1), software development analysts (2), data engineers (11) and artificial intelligence engineers (25). Similar data is offered by Fundación Telefónica's Employment Map, which also highlights four of the most in-demand profiles related to data:

- Data analyst: responsible for the management and exploitation of information, they are dedicated to the collection, analysis and exploitation of data, often through the creation of dashboards and reports.

- Database designer or database administrator: focused on designing, implementing and managing databases. As well as maintaining its security by implementing backup and recovery procedures in case of failures.

- Data engineer: responsible for the design and implementation of data architectures and infrastructures to capture, store, process and access data, optimising its performance and guaranteeing its security.

- Data scientist: focused on data analysis and predictive modelling, optimisation of algorithms and communication of results.

These are all jobs with good salaries and future prospects, but where there is still a large gap between men and women. According to European data, only 1 in 6 ICT specialists and 1 in 3 science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduates are women.

To develop data-related professions, you need, among others, knowledge of popular programming languages such as Python, R or SQL, and multiple data processing and visualisation tools, such as those detailed in these articles:

- Debugging and data conversion tools

- Data analysis tools

- Data visualisation tools

- Data visualisation libraries and APIs

- Geospatial visualisation tools

- Network analysis tools

The range of training courses on all these skills is growing all the time.

Future prospects

Nearly a quarter of all jobs (23%) will change in the next five years, according to the World Economic Forum's Future of Jobs 2023 Report. Technological advances will create new jobs, transform existing jobs and destroy those that become obsolete. Technical knowledge, related to areas such as artificial intelligence or Big Data, and the development of cognitive skills, such as analytical thinking, will provide great competitive advantages in the labour market of the future. In this context, policy initiatives to boost society's re-skilling , such as the European Digital Education Action Plan (2021-2027), will help to generate common frameworks and certificates in a constantly evolving world.

The technological revolution is here to stay and will continue to change our world. Therefore, those who start acquiring new skills earlier will be better positioned in the future employment landscape.

Data literacy has become a crucial issue in the digital age. This concept refers to the ability of people to understand how data is used, how it is accessed, created, analysed, used or reused, and communicated.

We live in a world where data and algorithms influence everyday decisions and the opportunities people have to live well. Its effect can be felt in areas ranging from advertising and employment provision to criminal justice and social welfare. It is therefore essential to understand how data is generated and used.

Data literacy can involve many areas, but we will focus on its relationship with digital rights on the one hand and Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the other. This article proposes to explore the importance of data literacy for citizenship, addressing its implications for the protection of individual and collective rights and the promotion of a more informed and critical society in a technological context where artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly important.

The context of digital rights

More and more studies studies increasingly indicate that effective participation in today's data-driven, algorithm-driven society requires data literacy indicating that effective participation in today's data-driven, algorithm-driven society requires data literacy. Civil rights are increasingly translating into digital rights as our society becomes more dependent on digital technologies and environments digital rights as our society becomes more dependent on digital technologies and environments. This transformation manifests itself in various ways:

- On the one hand, rights recognised in constitutions and human rights declarations are being explicitly adapted to the digital context. For example, freedom of expression now includes freedom of expression online, and the right to privacy extends to the protection of personal data in digital environments. Moreover, some traditional civil rights are being reinterpreted in the digital context. One example of this is the right to equality and non-discrimination, which now includes protection against algorithmic discrimination and against bias in artificial intelligence systems. Another example is the right to education, which now also extends to the right to digital education. The importance of digital skills in society is recognised in several legal frameworks and documents, both at national and international level, such as the Organic Law 3/2018 on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights (LOPDGDD) in Spain. Finally, the right of access to the internet is increasingly seen as a fundamental right, similar to access to other basic services.

- On the other hand, rights are emerging that address challenges unique to the digital world, such as the right to be forgotten (in force in the European Union and some other countries that have adopted similar legislation1), which allows individuals to request the removal of personal information available online, under certain conditions. Another example is the right to digital disconnection (in force in several countries, mainly in Europe2), which ensures that workers can disconnect from work devices and communications outside working hours. Similarly, there is a right to net neutrality to ensure equal access to online content without discrimination by service providers, a right that is also established in several countries and regions, although its implementation and scope may vary. The EU has regulations that protect net neutrality, including Regulation 2015/2120, which establishes rules to safeguard open internet access. The Spanish Data Protection Act provides for the obligation of Internet providers to provide a transparent offer of services without discrimination on technical or economic grounds. Furthermore, the right of access to the internet - related to net neutrality - is recognised as a human right by the United Nations (UN).

This transformation of rights reflects the growing importance of digital technologies in all aspects of our lives.

The context of artificial intelligence

The relationship between AI development and data is fundamental and symbiotic, as data serves as the basis for AI development in a number of ways:

- Data is used to train AI algorithms, enabling them to learn, detect patterns, make predictions and improve their performance over time.

- The quality and quantity of data directly affect the accuracy and reliability of AI systems. In general, more diverse and complete datasets lead to better performing AI models.

- The availability of data in various domains can enable the development of AI systems for different use cases.

Data literacy has therefore become increasingly crucial in the AI era, as it forms the basis for effectively harnessing and understanding AI technologies.

In addition, the rise of big data and algorithms has transformed the mechanisms of participation, presenting both challenges and opportunities. Algorithms, while they may be designed to be fair, often reflect the biases of their creators or the data they are trained on. This can lead to decisions that negatively affect vulnerable groups.

In this regard, legislative and academic efforts are being made to prevent this from happening. For example, the EuropeanArtificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) includes safeguards to avoid harmful biases in algorithmic decision-making. For example, it classifies AI systems according to their level of potential risk and imposes stricter requirements on high-risk systems. In addition, it requires the use of high quality data to train the algorithms, minimising bias, and provides for detailed documentation of the development and operation of the systems, allowing for audits and evaluations with human oversight. It also strengthens the rights of persons affected by AI decisions, including the right to challenge decisions made and their explainability, allowing affected persons to understand how a decision was reached.

The importance of digital literacy in both contexts

Data literacy helps citizens make informed decisions and understand the full implications of their digital rights, which are also considered, in many respects, as mentioned above, to be universal civil rights. In this context, data literacy serves as a critical filter for full civic participation that enables citizens to influence political and social decisions full civic participation that enables citizens to influence political and social decisions. That is,those who have access to data and the skills and tools to navigate the data infrastructure effectively can intervene and influencepolitical and social processes in a meaningful way , something which promotes the Open Government Partnership.

On the other hand, data literacy enables citizens to question and understand these processes, fostering a culture of accountability and transparency in the use of AI. There arealso barriers to participation in data-driven environments. One of these barriers is the digital divide (i.e. deprivation of access to infrastructure, connectivity and training, among others) and, indeed, lack of data literacy. The latter is therefore a crucial concept for overcoming the challenges posed by datification datification of human relations and the platformisation of content and services.

Recommendations for implementing a preparedness partnership

Part of the solution to addressing the challenges posed by the development of digital technology is to include data literacy in educational curricula from an early age.

This should cover:

- Data basics: understanding what data is, how it is collected and used.

- Critical analysis: acquisition of the skills to evaluate the quality and source of data and to identify biases in the information presented. It seeks to recognise the potential biases that data may contain and that may occur in the processing of such data, and to build capacity to act in favour of open data and its use for the common good.

- Rights and regulations: information on data protection rights and how European laws affect the use of AI. This area would cover all current and future regulation affecting the use of data and its implication for technology such as AI.

- Practical applications: the possibility of creating, using and reusing open data available on portals provided by governments and public administrations, thus generating projects and opportunities that allow people to work with real data, promoting active, contextualised and continuous learning.

By educating about the use and interpretation of data, it fosters a more critical society that is able to demand accountability in the use of AI. New data protection laws in Europe provide a framework that, together with education, can help mitigate the risks associated with algorithmic abuse and promote ethical use of technology. In a data-driven society, where data plays a central role, there is a need to foster data literacy in citizens from an early age.

1The right to be forgotten was first established in May 2014 following a ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union. Subsequently, in 2018, it was reinforced with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)which explicitly includes it in its Article 17 as a "right of erasure". In July 2015, Russia passed a law allowing citizens to request the removal of links on Russian search engines if the information"violates Russian law or if it is false or outdated". Turkey has established its own version of the right to be forgotten, following a similar model to that of the EU. Serbia has also implemented a version of the right to be forgotten in its legislation. In Spain, the Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales (LOPD) regulates the right to be forgotten, especially with regard to debt collection files. In the United Statesthe right to be forgotten is considered incompatible with the Constitution, mainly because of the strong protection of freedom of expression. However, there are some related regulations, such as the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970, which allows in certain situations the deletion of old or outdated information in credit reports.

2Some countries where this right has been established include Spain, regulated by Article 88 of Organic Law 3/2018 on Personal Data Protection; France, which, in 2017, became the first country to pass a law on the right to digital disconnection; Germany, included in the Working Hours and Rest Time Act(Arbeitszeitgesetz); Italy, under Law 81/201; and Belgium. Outside Europe, it is, for example, in Chile.

Content prepared by Miren Gutiérrez, PhD and researcher at the University of Deusto, expert in data activism, data justice, data literacy and gender disinformation. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

In the fast-paced world of Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI), there are several concepts that have become fundamental to understanding and harnessing the potential of this technology. Today we focus on four: Small Language Models(SLM), Large Language Models(LLM), Retrieval Augmented Generation(RAG) and Fine-tuning. In this article, we will explore each of these terms, their interrelationships and how they are shaping the future of generative AI.

Let us start at the beginning. Definitions

Before diving into the details, it is important to understand briefly what each of these terms stands for:

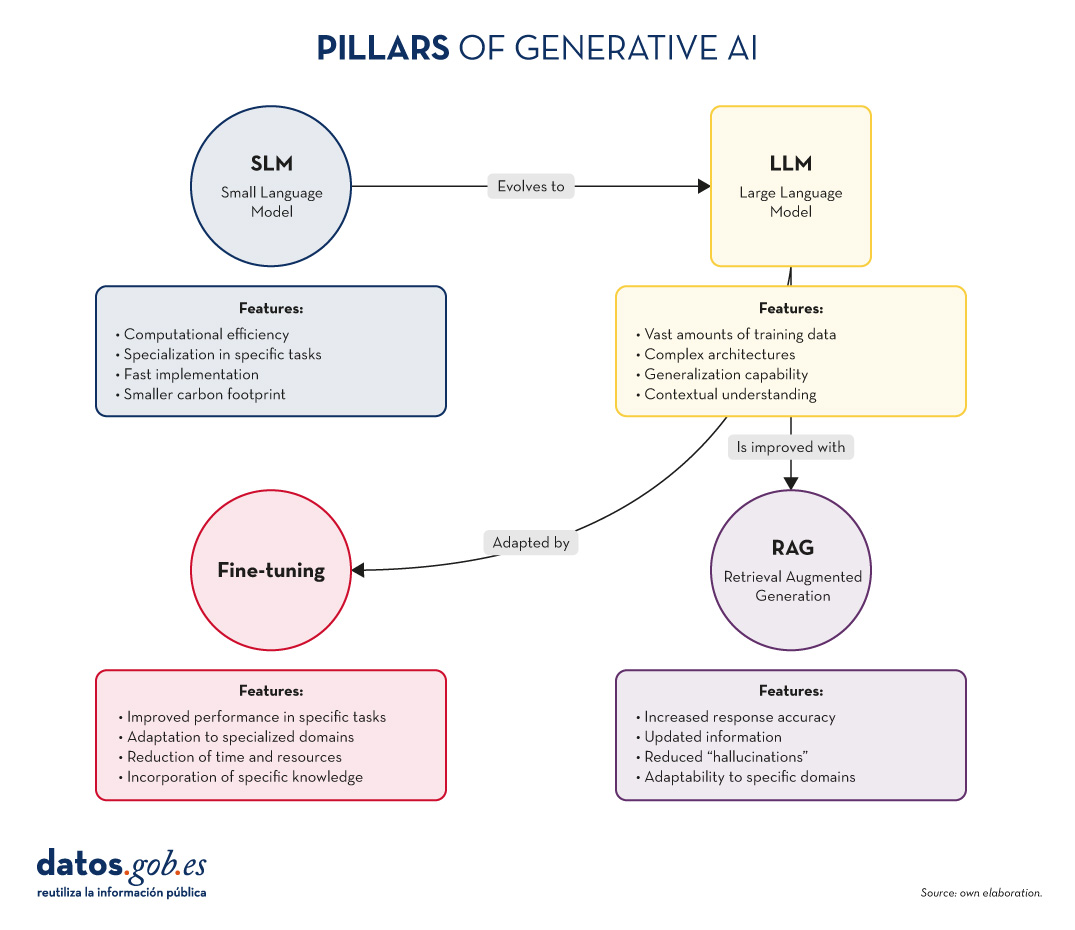

The first two concepts (SLM and LLM) that we address are what are known as language models. A language model is an artificial intelligence system that understands and generates text in human language, as do chatbots or virtual assistants. The following two concepts (Fine Tuning and RAG) could be defined as optimisation techniques for these previous language models. Ultimately, these techniques, with their respective approaches as discussed below, improve the answers and the content returned to the questioner. Let's go into the details:

- SLM (Small Language Models): More compact and specialised language models, designed for specific tasks or domains.

- LLM (Large Language Models): Large-scale language models, trained on vast amounts of data and capable of performing a wide range of linguistic tasks.

- RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): A technique that combines the retrieval of relevant information with text generation to produce more accurate and contextualised responses.

- Fine-tuning: The process of tuning a pre-trained model for a specific task or domain, improving its performance in specific applications.

Now, let's dig deeper into each concept and explore how they interrelate in the Generative AI ecosystem.

Figure 1. Pillars of Generative AI. Own elaboration.

SLM: The power of specialisation

Increased efficiency for specific tasks

Small Language Models (SLMs) are AI models designed to be lighter and more efficient than their larger counterparts. Although they have fewer parameters, they are optimised for specific tasks or domains.

Key characteristics of SLMs:

- Computational efficiency: They require fewer resources for training and implementation.

- Specialisation: They focus on specific tasks or domains, achieving high performance in specific areas.

- Rapid implementation: Ideal for resource-constrained devices or applications requiring real-time responses.

- Lower carbon footprint: Being smaller, their training and use consumes less energy.

SLM applications:

- Virtual assistants for specific tasks (e.g. booking appointments).

- Personalised recommendation systems.

- Sentiment analysis in social networks.

- Machine translation for specific language pairs.

LLM: The power of generalisation

The revolution of Large Language Models

LLMs have transformed the Generative AI landscape, offering amazing capabilities in a wide range of language tasks.

Key characteristics of LLMs:

- Vast amounts of training data: They train with huge corpuses of text, covering a variety of subjects and styles.

- Complex architectures: They use advanced architectures, such as Transformers, with billions of parameters.

- Generalisability: They can tackle a wide variety of tasks without the need for task-specific training.

- Contextual understanding: They are able to understand and generate text considering complex contexts.

LLM applications:

- Generation of creative text (stories, poetry, scripts).

- Answers to complex questions and reasoning.

- Analysis and summary of long documents.

- Advanced multilingual translation.

RAG: Boosting accuracy and relevance

The synergy between recovery and generation

As we explored in our previous article, RAG combines the power of information retrieval models with the generative capacity of LLMs. Its key aspects are:

Key features of RAG:

- Increased accuracy of responses.

- Capacity to provide up-to-date information.

- Reduction of "hallucinations" or misinformation.

- Adaptability to specific domains without the need to completely retrain the model.

RAG applications:

- Advanced customer service systems.

- Academic research assistants.

- Fact-checking tools for journalism.

- AI-assisted medical diagnostic systems.

Fine-tuning: Adaptation and specialisation

Refining models for specific tasks

Fine-tuning is the process of adjusting a pre-trained model (usually an LLM) to improve its performance in a specific task or domain. Its main elements are as follows:

Key features of fine-tuning:

- Significant improvement in performance on specific tasks.

- Adaptation to specialised or niche domains.

- Reduced time and resources required compared to training from scratch.

- Possibility of incorporating specific knowledge of the organisation or industry.

Fine-tuning applications:

- Industry-specific language models (legal, medical, financial).

- Personalised virtual assistants for companies.

- Content generation systems tailored to particular styles or brands.

- Specialised data analysis tools.

Here are a few examples

Many of you familiar with the latest news in generative AI will be familiar with these examples below.

SLM: The power of specialisation

Ejemplo: BERT for sentiment analysis

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) is an example of SLM when used for specific tasks. Although BERT itself is a large language model, smaller, specialised versions of BERT have been developed for sentiment analysis in social networks.

For example, DistilBERT, a scaled-down version of BERT, has been used to create sentiment analysis models on X (Twitter). These models can quickly classify tweets as positive, negative or neutral, being much more efficient in terms of computational resources than larger models.

LLM: The power of generalisation

Ejemplo: OpenAI GPT-3

GPT-3 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3) is one of the best known and most widely used LLMs. With 175 billion parameters, GPT-3 is capable of performing a wide variety of natural language processing tasks without the need for task-specific training.

A well-known practical application of GPT-3 is ChatGPT, OpenAI's conversational chatbot. ChatGPT can hold conversations on a wide variety of topics, answer questions, help with writing and programming tasks, and even generate creative content, all using the same basic model.

Already at the end of 2020 we introduced the first post on GPT-3 as a great language model. For the more nostalgic ones, you can check the original post here.

RAG: Boosting accuracy and relevance

Ejemplo: Anthropic's virtual assistant, Claude

Claude, the virtual assistant developed by Anthropic, is an example of an application using RAGtechniques. Although the exact details of its implementation are not public, Claude is known for his ability to provide accurate and up-to-date answers, even on recent events.

In fact, most generative AI-based conversational assistants incorporate RAG techniques to improve the accuracy and context of their responses. Thus, ChatGPT, the aforementioned Claude, MS Bing and the like use RAG.

Fine-tuning: Adaptation and specialisation

Ejemplo: GPT-3 fine-tuned for GitHub Copilot

GitHub Copilot, the GitHub and OpenAI programming assistant, is an excellent example of fine-tuning applied to an LLM. Copilot is based on a GPT model (possibly a variant of GPT-3) that has been specificallyfine-tunedfor scheduling tasks.

The base model was further trained with a large amount of source code from public GitHub repositories, allowing it to generate relevant and syntactically correct code suggestions in a variety of programming languages. This is a clear example of how fine-tuning can adapt a general purpose model to a highly specialised task.

Another example: in the datos.gob.es blog, we also wrote a post about applications that used GPT-3 as a base LLM to build specific customised products.

Interrelationships and synergies

These four concepts do not operate in isolation, but intertwine and complement each other in the Generative AI ecosystem:

- SLM vs LLM: While LLMs offer versatility and generalisability, SLMs provide efficiency and specialisation. The choice between one or the other will depend on the specific needs of the project and the resources available.

- RAG and LLM: RAG empowers LLMs by providing them with access to up-to-date and relevant information. This improves the accuracy and usefulness of the answers generated.

- Fine-tuning and LLM: Fine-tuning allows generic LLMs to be adapted to specific tasks or domains, combining the power of large models with the specialisation needed for certain applications.

- RAG and Fine-tuning: These techniques can be combined to create highly specialised and accurate systems. For example, a LLM with fine-tuning for a specific domain can be used as a generative component in a RAGsystem.

- SLM and Fine-tuning: Fine-tuning can also be applied to SLM to further improve its performance on specific tasks, creating highly efficient and specialised models.

Conclusions and the future of AI

The combination of these four pillars is opening up new possibilities in the field of Generative AI:

- Hybrid systems: Combination of SLM and LLM for different aspects of the same application, optimising performance and efficiency.

- AdvancedRAG : Implementation of more sophisticated RAG systems using multiple information sources and more advanced retrieval techniques.

- Continuousfine-tuning : Development of techniques for the continuous adjustment of models in real time, adapting to new data and needs.

- Personalisation to scale: Creation of highly customised models for individuals or small groups, combining fine-tuning and RAG.

- Ethical and responsible Generative AI: Implementation of these techniques with a focus on transparency, verifiability and reduction of bias.

SLM, LLM, RAG and Fine-tuning represent the fundamental pillars on which the future of Generative AI is being built. Each of these concepts brings unique strengths:

- SLMs offer efficiency and specialisation.

- LLMs provide versatility and generalisability.

- RAG improves the accuracy and relevance of responses.

- Fine-tuning allows the adaptation and customisation of models.

The real magic happens when these elements combine in innovative ways, creating Generative AI systems that are more powerful, accurate and adaptive than ever before. As these technologies continue to evolve, we can expect to see increasingly sophisticated and useful applications in a wide range of fields, from healthcare to creative content creation.

The challenge for developers and researchers will be to find the optimal balance between these elements, considering factors such as computational efficiency, accuracy, adaptability and ethics. The future of Generative AI promises to be fascinating, and these four concepts will undoubtedly be at the heart of its development and application in the years to come.

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, expert in Digital Transformation and Innovation. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is revolutionising the way we create and consume content. From automating repetitive tasks to personalising experiences, AI offers tools that are changing the landscape of marketing, communication and creativity.

These artificial intelligences need to be trained with data that are fit for purpose and not copyrighted. Open data is therefore emerging as a very useful tool for the future of AI.

The Govlab has published the report "A Fourth Wave of Open Data? Exploring the Spectrum of Scenarios for Open Data and Generative AI" to explore this issue in more detail. It analyses the emerging relationship between open data and generative AI, presenting various scenarios and recommendations. Their key points are set out below.

The role of data in generative AI

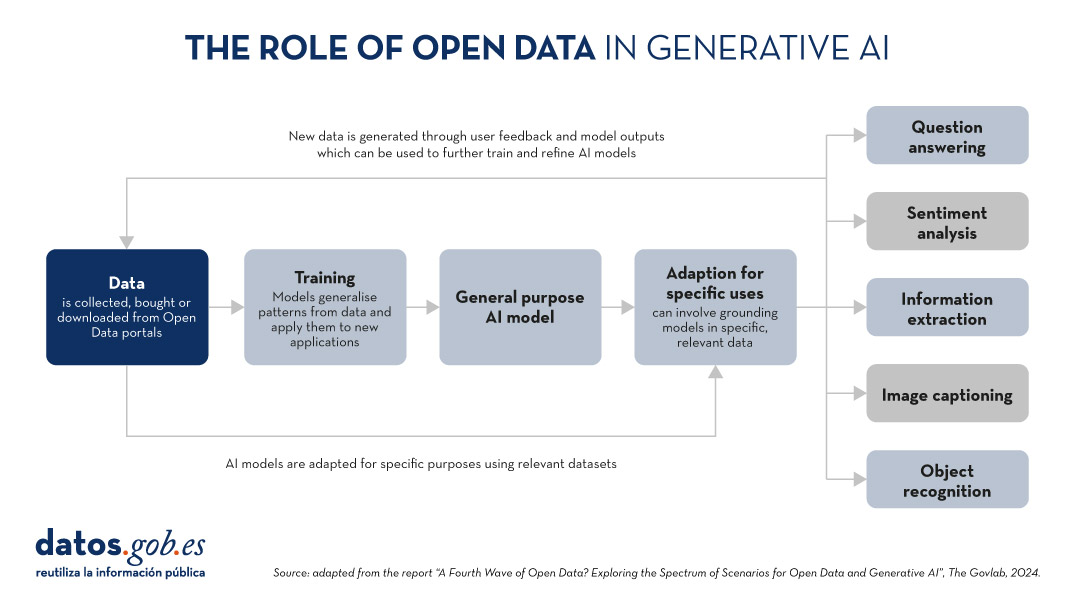

Data is the fundamental basis for generative artificial intelligence models. Building and training such models requires a large volume of data, the scale and variety of which is conditioned by the objectives and use cases of the model.

The following graphic explains how data functions as a key input and output of a generative AI system. Data is collected from various sources, including open data portals, in order to train a general-purpose AI model. This model will then be adapted to perform specific functions and different types of analysis, which in turn generate new data that can be used to further train models.

Figure 1. The role of open data in generative AI, adapted from the report “A Fourth Wave of Open Data? Exploring the Spectrum of Scenarios for Open Data and Generative AI”, The Govlab, 2024.

5 scenarios where open data and artificial intelligence converge

In order to help open data providers ''prepare'' their data for generative AI, The Govlab has defined five scenarios outlining five different ways in which open data and generative AI can intersect. These scenarios are intended as a starting point, to be expanded in the future, based on available use cases.

| Scenario | Function | Quality requirements | Metadata requirements | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-training | Training the foundational layers of a generative AI model with large amounts of open data. | High volume of data, diverse and representative of the application domain and non-structured usage. | Clear information on the source of the data. | Data from NASA''s Harmonized Landsat Sentinel-2 (HLS) project were used to train the geospatial foundational model watsonx.ai. |

| Adaptation | Refinement of a pre-trained model with task-specific open data, using fine-tuning or RAG techniques. | Tabular and/or unstructured data of high accuracy and relevance to the target task, with a balanced distribution. | Metadata focused on the annotation and provenance of data to provide contextual enrichment. | Building on the LLaMA 70B model, the French Government created LLaMandement, a refined large language model for the analysis and drafting of legal project summaries. They used data from SIGNALE, the French government''s legislative platform. |

| Inference and Insight Generation | Extracting information and patterns from open data using a trained generative AI model. | High quality, complete and consistent tabular data. | Descriptive metadata on the data collection methods, source information and version control. | Wobby is a generative interface that accepts natural language queries and produces answers in the form of summaries and visualisations, using datasets from different offices such as Eurostat or the World Bank. |

| Data Augmentation | Leveraging open data to generate synthetic data or provide ontologies to extend the amount of training data. | Tabular and/or unstructured data which is a close representation of reality, ensuring compliance with ethical considerations. | Transparency about the generation process and possible biases. | A team of researchers adapted the US Synthea model to include demographic and hospital data from Australia. Using this model, the team was able to generate approximately 117,000 region-specific synthetic medical records. |

| Open-Ended Exploration | Exploring and discovering new knowledge and patterns in open data through generative models. | Tabular data and/or unstructured, diverse and comprehensive. | Clear information on sources and copyright, understanding of possible biases and limitations, identification of entities. | NEPAccess is a pilot to unlock access to data related to the US National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) through a generative AI model. It will include functions for drafting environmental impact assessments, data analysis, etc. |

Figure 2. Five scenarios where open data and Artificial Intelligence converge, adapted from the report “A Fourth Wave of Open Data? Exploring the Spectrum of Scenarios for Open Data and Generative AI”, The Govlab, 2024.

You can read the details of these scenarios in the report, where more examples are explained. In addition, The Govlab has also launched an observatory where it collects examples of intersections between open data and generative artificial intelligence. It includes the examples in the report along with additional examples. Any user can propose new examples via this form. These examples will be used to further study the field and improve the scenarios currently defined.

Among the cases that can be seen on the web, we find a Spanish company: Tendios. This is a software-as-a-service company that has developed a chatbot to assist in the analysis of public tenders and bids in order to facilitate competition. This tool is trained on public documents from government tenders.

Recommendations for data publishers

To extract the full potential of generative AI, improving its efficiency and effectiveness, the report highlights that open data providers need to address a number of challenges, such as improving data governance and management. In this regard, they contain five recommendations:

- Improve transparency and documentation. Through the use of standards, data dictionaries, vocabularies, metadata templates, etc. It will help to implement documentation practices on lineage, quality, ethical considerations and impact of results.

- Maintaining quality and integrity. Training and routine quality assurance processes are needed, including automated or manual validation, as well as tools to update datasets quickly when necessary. In addition, mechanisms for reporting and addressing data-related issues that may arise are needed to foster transparency and facilitate the creation of a community around open datasets.

- Promote interoperability and standards. It involves adopting and promoting international data standards, with a special focus on synthetic data and AI-generated content.