Open data can be the basis for various disruptive technologies, such as Artificial Intelligence, which can lead to improvements in society and the economy. These infographics address both tools for working with data and examples of the use of open data in these new technologies. New content will be published periodically.

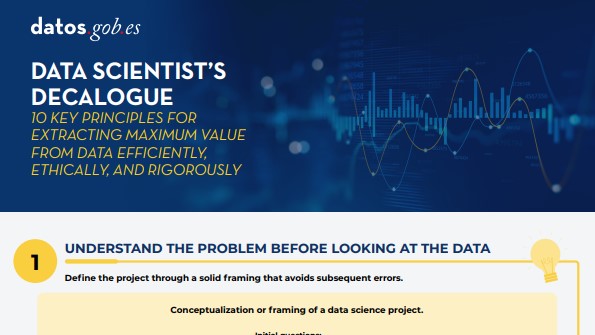

Data Scientist's decalogue

|

Published: octubre 2025 From understanding the problem before looking at the data, to visualizing to communicate and staying up to date, this decalogue offers a comprehensive overview of the life cycle of a responsible and well-structured data project. |

Open data visualization with open source tools

|

Published: june 2025 This infographic compiles data visualisation tools, the last step of exploratory data analysis. It is the second part of the infographic on open data analysis with open source tools. |

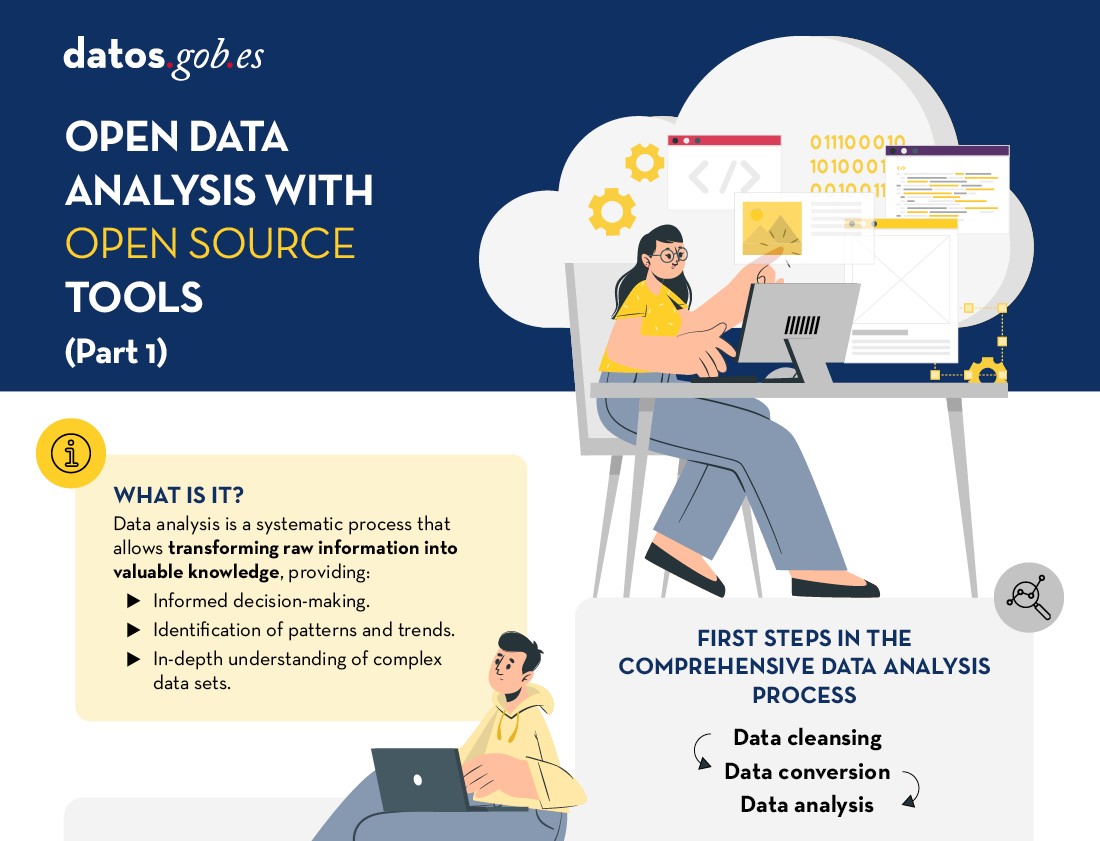

Open data analysis with open source tools

|

Published: March 2025 EDA is the application of a set of statistical techniques aimed at exploring, describing and summarising the nature of data in a way that ensures its objectivity and interoperability. In this infographic, we compile free tools to perform the first three steps of data analysis. |

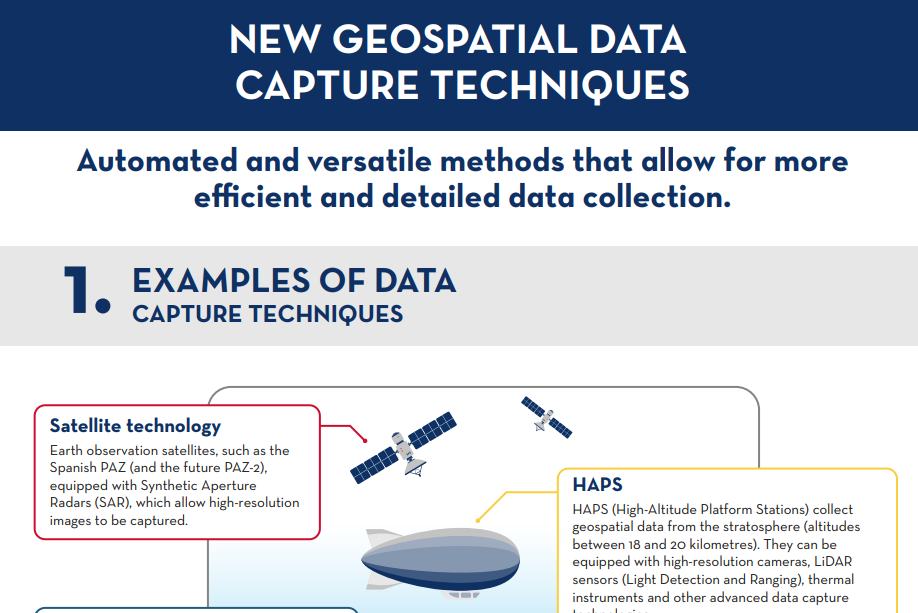

New geospatial data capture techniques

|

Published: January 2025 Geospatial data capture is essential for understanding the environment, making decisions and designing effective policies. In this infographic, we will explore new methods of data capture. |

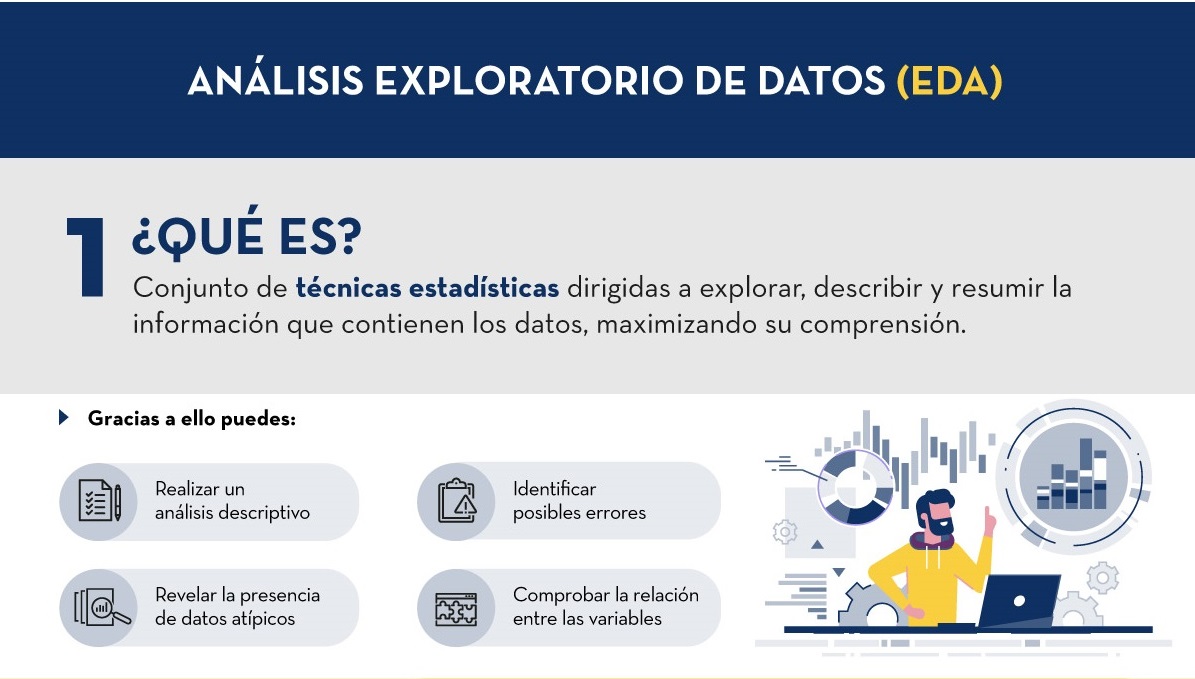

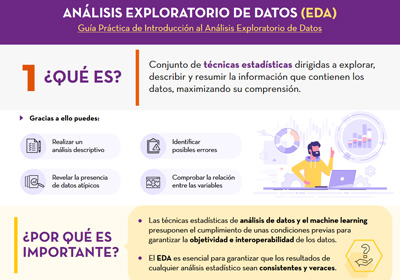

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

|

Published: November 2024 Based on the report “Guía Práctica de Introducción al Análisis Exploratorio de Datos”, an infographic has been prepared that summarises in a simple way what this technique consists of, its benefits and the steps to follow in order to carry it out correctly. |

Glossary of open data and related new technologies

|

Published: April 2024 and May 2024 This page contains two infographics. The first infographic contains the definition of various terms related to open data, while the second focuses on new technologies related to data. |

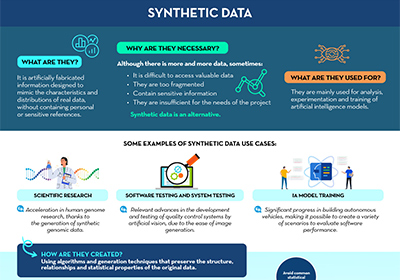

Synthetic Data (EDA)

|

Published: October 2023 Based on the report ''Synthetic Data: What are they and what are they used for?'', an infographic has been prepared that summarizes in a simple way the main keys of synthetic data and how they overcome the limitations of real data. |

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

|

Published: September 2021 Based on the report "A Practical Introductory Guide to Exploratory Data Analysis", an infographic has been prepared that summarizes in a simple way what this technique consists of, its benefits and which are the steps to follow to perform it correctly. |

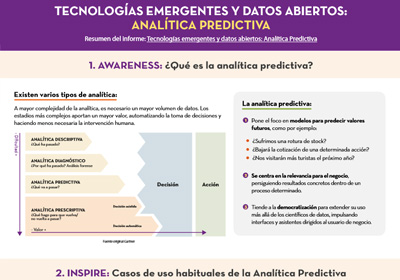

Emerging Technologies and Open Data: Predictive Analytics

|

Published: April 2021 This infographic is a summary of the report "Emerging Technologies and Open Data: Predictive Analytics", from the "Awareness, Inspire, Action" series. It explains what predictive analytics is and its most common use cases. It also shows a practical example, using the dataset related to traffic accident in the city of Madrid. |

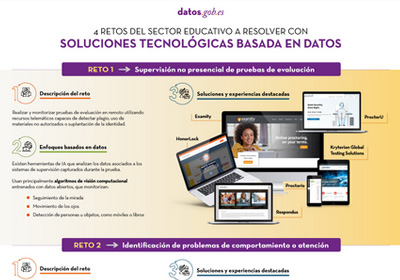

Data-driven education technology to improve learning in the classroom and at home

|

Published: August 2020 Innovative educational technology based on data and artificial intelligence can address some of the challenges facing the education system, such as monitoring online assessment tests, identifying behavioral problems, personalized training or improving performance on standardized tests. This infographic, a summary of the report "Data-driven educational technology to improve learning in the classroom and at home", shows some examples. |

Open data is not only a matter of public administrations, more and more companies are also betting on them. This is the case of Microsoft, who has provided access to selected open data in Azure designed for the training of Machine Learning models. He also collaborates in the development of multiple projects in order to promote open data. In Spain, it has collaborated in the development of the platform HealthData 29, intended for the publication of open data to promote medical research.

We have interviewed Belén Gancedo, Director of Education at Microsoft Ibérica and member of the jury in the III edition of the Aporta Challenge,focused on the value of data for the education sector. We met with her to talk about the importance of digital education and innovative data-driven solutions, as well as the importance of open data in the business sector.

Complete interview:

1. What challenges in the education sector, to which it is urgent to respond, has the pandemic in Spain revealed?

Technology has become an essential element in the new way of learning and teaching. During the last months, marked by the pandemic, we have seen how a hybrid education model - face-to-face and remotely - has changed in a very short time. We have seen examples of centers that, in record time, in less than 2 weeks, have had to accelerate the digitization plans they already had in mind.

Technology has gone from being a temporary lifeline, enabling classes to be taught in the worst stage of the pandemic, to becoming a fully integrated part of the teaching methodology of many schools. According to a recent YouGov survey commissioned by Microsoft, 71% of elementary and middle school educators say that technology has helped them improve their methodology and improved their ability to teach. In addition, 82% of teachers report that the pace at which technology has driven innovation in teaching and learning has accelerated in the past year.

Before this pandemic, in some way, those of us who had been dedicating ourselves to education were the ones who defended the need to digitally transform the sector and the benefits that technology brought to it. However, the experience has served to make everyone aware of the benefits of the application of technology in the educational environment. In that sense, there has been an enormous advance. We have seen a huge increase in the use of our Teams tool, which is already used by more than 200 million students, teachers, and education staff around the world.

The biggest challenges, then, currently, are to not only take advantage of data and Artificial Intelligence to provide more personalized experiences and operate with greater agility, but also the integration of technology with pedagogy, which will allow more flexible, attractive learning experiences and inclusive. Students are increasingly diverse, and so are their expectations about the role of college education in their journey to employment.

The biggest challenges, then, currently, are to not only take advantage of data and Artificial Intelligence to provide more personalized experiences and operate with greater agility, but also the integration of technology with pedagogy, which will allow more flexible, attractive learning experiences and inclusive.

2. How can open data help drive these improvements? What technologies need to be implemented to drive improvements in the efficiency and effectiveness of the learning system?

Data is in all aspects of our lives. Although it may not be related to the mathematics or algorithm that governs predictive analytics, its impact can be seen in education by detecting learning difficulties before it is too late. This can help teachers and institutions gain a greater understanding of their students and information on how to help solve their problems.

Predictive analytics platforms and Artificial Intelligence technology have already been used with very positive results by different industries to understand user behavior and improve decision-making. With the right data, the same can be applied in classrooms. On the one hand, it helps to personalize and drive better learning outcomes, to create inclusive and personalized learning experiences, so that each student is empowered to succeed. If its implementation is correct, it allows a better and greater monitoring of the needs of the student, who becomes the center of learning and who will enjoy permanent support.

At Microsoft we want to be the ideal travel companion for the digital transformation of the education sector. We offer educational entities the best solutions -cloud and hardware- to prepare students for their professional future, in a complete environment of collaboration and communication for the classroom, both in face-to-face and online models. Solutions like Office 365 Education and the Surface device are designed precisely to drive collaboration both inside and outside the classroom. The educational version of Microsoft Teams makes a virtual classroom possible. It is a free tool for schools and universities that integrates conversations, video calls, content, assignments and applications in one place, allowing teachers to create learning environments that are lively and accessible from mobile devices,

And, in addition, we make available to schools, teachers and students devices specifically designed for the educational environment, such as the Surface Go 2, expressly designed for the educational environment. It is an evolutionary device, that is, it adapts to any educational stage and boosts the creativity of students thanks to its power, versatility and safety. This device allows the mobility of both teachers and students inside and outside the classroom; connectivity with other peripheral devices (printers, cameras ...); and includes the Microsoft Classroom Pen for natural writing and drawing in digital ink.

3. There is increasing demand for digital skills and competencies related to data. In this sense, the National Plan for Digital Skills, which includes the digitization of education and the development of digital skills for learning. What changes should be made in educational programs in order to promote the acquisition of digital knowledge by students?

Without a doubt, one of the biggest challenges we face today is the lack of training and digital skills. According to a study carried out by Microsoft and EY, 57% of the companies surveyed expect AI to have a high or very high impact in business areas that are "totally unknown to companies today."

There is a clear opportunity for Spain to lead in Europe in digital talent, consolidating itself as one of the most attractive countries to attract and retain this talent. A recent LinkedIn study anticipates that two million technology-related jobs will be created in Spain in the next five years, not only in the technology industry, but also,and above all, in companies in other sectors of activity that seek to incorporate the necessary talent to carry out their transformation. However, there is a shortage of professionals with skills and training in digital skills. According to data from the Digital Economy and Society Index Report published annually by the European Commission, Spain is below the European average in most of the indicators that refer to the digital skills of Spanish professionals.

There is, therefore, an urgent demand to train qualified talent with digital skills, data management, AI, machine learning ... Technology-related profiles are among the most difficult to find and, in the near future, those related to technology data analytics, cloud computing and application development.

For this, adequate training is necessary, not only in the way of teaching, but also in the curricular content. Any career, not just those in the STEM field, would need to include subjects related to technology and AI, which will define the future. The use of AI reaches any field, not only technology, therefore, students of any type of career -Law, Journalism ... - to give some examples of non-STEM careers, need qualified training in technology such as AI or data science, since they will have to apply it in their professional future.

We must bet on public-private collaborations and involve the technology industry, public administrations, the educational community, adapting the curricular contents of the University to the labor reality- and third sector entities, with the aim of promoting employability and professional recycling. In this way, the training of professionals in areas such as quantum computing, Artificial Intelligence, or data analytics and we can aspire to digital leadership.

In the next five years, two million technology-related jobs will be created in Spain, not only in the technology industry, but also, and above all, in companies in other sectors of activity that seek to incorporate the necessary talent to lead carry out your transformation.

4. Even today we find a disparity between the number of men and women who choose professional branches related to technology. What is needed to promote the role of women in technology?

According to the National Observatory of Telecommunications and Information Society -ONTSI- (July 2020), the digital gender gap has been progressively reduced in Spain, going from 8.1 to 1 point, although women maintain an unfavorable position in digital skills and Internet use. In advanced skills, such as programming, the gap in Spain is 6.8 points, the EU average being 8 points. The percentage of researchers in the ICT services sector drops to 23.4%. And in terms of the percentage of graduates in STEM, Spain ranks 12th within the EU, with a difference between the sexes of 17 points.

Without a doubt, there is still a long way to go. One of the main barriers that women face in the technology sector and when it comes to entrepreneurship are stereotypes and cultural tradition. The masculinized environment of technical careers and stereotypes about those who are dedicated to technology make them unattractive careers for women.

Digitization is boosting the economy and promoting business competitiveness,as well as generating an increase in the creation of specialized employment. Perhaps the most interesting thing about the impact of digitization on the labor market is that these new jobs are not only being created in the technology industry, but also in companies from all sectors, which need to incorporate specialized talent and digital skills.

Therefore, there is an urgent demand to train qualified talent with digital capabilities and this talent must be diverse. The woman cannot be left behind. It is time to tackle gender inequality, and alert everyone to this enormous opportunity, regardless of their gender. STEM careers are an ideal future option for anyone, regardless of gender.

Forfavor the female presence in the technology sector, in favor of a digital era without exclusion, at Microsoft we have launched different initiatives that seek to banish stereotypes and encourage girls and young people to take an interest in science and technology and make them see that they they can also be the protagonists of the digital society. In addition to the WONNOW Awards that we convened with CaixaBank, we also participate and collaborate in many initiatives, such as the Ada Byron Awards together with the University of Deusto, to help give visibility to the work of women in the STEM field, so that they are references of those who They are about to come.

The digital gender gap has been progressively reduced in Spain, going from 8.1 to 1 point, although women maintain an unfavorable position in digital skills and Internet use. In advanced skills, such as programming, the gap in Spain is 6.8 points, the EU average being 8 points.

5. How can initiatives like hackathons, challenge or challenges help drive data-driven innovation? How was your experience in the III Aporta Challenge?

These types of initiatives are key to that much-needed change. At Microsoft we are constantly organizing hackathons on a global, regional and local scale, to innovate in different priority areas for the company, such as education.

But we go further. We also use these tools in class. One of Microsoft's bets is the projects STEM hacking.These are projects in which the “maker” concept of learning by doing with programming and robotics is mixed, through the use of everyday materials. What's more,They are made up of activities that allow teachers to guide their students to construct and create scientific instruments and project-based tools to visualize data through science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Our projects -both Hacking STEM as well as coding and computational language through the use of free tools such as Make Code- aim to bring programming and robotics to any subject in a transversal way, and why not, learn programming in a Latin class or in a biology one.

My experience in the III Aporta Challenge has been fantastic because it has allowed me to learn about incredible ideas and projects where the usefulness of the amount of data available becomes a reality and is put at the service of improving the education of all. There has been a lot of participation and, in addition, with very careful and worked presentations. The truth is that I would like to take this opportunity to thank everyone who has participated and also congratulate the winners.

6. A year ago, Microsoft launched a campaign to promote open data in order to close the gap between countries and companies that have the necessary data to innovate and those that do not. What has the project consisted of? What progress has been made?

Microsoft's global initiative Open Data Campaign seeks to help close the growing “data gap” between the small number of technology companies that benefit most from the data economy today and other organizations that are hampered by lack of access to data or lack of capabilities to use the ones you already have.

Microsoft believes that more needs to be done to help organizations share and collaborate around data so that businesses and governments can use it to meet the challenges they face, as the ability to share data has huge benefits. And not only for the business environment, but they also play a critical role in helping us understand and address major challenges, such as climate change, or health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. To take full advantage of them, it is necessary to develop the ability to share them in a safe and reliable way, and to allow them to be used effectively.

Within the Open Data Campaign initiative, Microsoft has announced 5 great principles that will guide how the company itself approaches how to share its data with others:

- Open- Will work to make relevant data on large social issues as open as possible.

- Usable- Invest in creating new technologies and tools, governance mechanisms and policies so that data can be used by everyone.

- Boosters- Microsoft will help organizations generate value from their data and develop AI talent to use it effectively.

- Insurance- Microsoft will employ security controls to ensure data collaboration is secure at the operational level.

- Private- Microsoft will help organizations protect the privacy of individuals in data-sharing collaborations that involve personally identifiable information.

We continue to make progress in this regard. Last year, Microsoft Spain, next to Foundation 29, the Chair on Privacy and Digital Transformation Microsoft-Universitat de València and with the legal advice of the law firm J&A Garrigues have created the Guide "Health Data"that describes the technical and legal framework to carry out the creation of a public repository of health systems data, and that these can be shared and used in research environments and LaLiga is one of the entities that has shared, in June of this year, its anonymized data.

Data is the beginning of everything and one of our biggest responsibilities as a technology company is to help conserve the ecosystem on a large scale, on a planetary level. For this, the greatest challenge is to consolidate not only all the available data, but the artificial intelligence algorithms that allow access to it and allow making decisions, creating predictive models, scenarios with updated information from multiple sources. For this reason, Microsoft launched the concept of Planetary Computer, based on Open Data, to make more than 10 Petabytes of data - and growing - available to scientists, biologists, startups and companies, free of charge, from multiple sources (biodiversity, electrification , forestry, biomass, satellite), APIs, Development Environments and applications (predictive model, etc.) to create a greater impact for the planet.

Microsoft's global initiative Open Data Campaign seeks to help close the growing “data gap” between the small number of technology companies that benefit most from the data economy today and other organizations that are hampered by lack of access to data or lack of capabilities to use the ones you already have.

7. They also offer some open data sets through their Azure Open Datasets initiative. What kind of data do they offer? How can users use them?

This initiative seeks that companies improve the accuracy of the predictions of their Machine Learning models and reduce the time of data preparation, thanks to selected data sets of public access, ready to use and easily accessible from the Azure services.

There is data of all kinds: health and genomics, transport, labor and economy, population and security, common data ... that can be used in multiple ways. And it is also possible to contribute datasets to the community.

8. Which are the Microsoft's future plans for open data?

After a year with the Opendata campaign, we have had many learnings and, in collaboration with our partners, we are going to focus next year on practical aspects that make the process of data sharing easier. We just started publishing materials for organizations to see the nuts and bolts of how to start sharing data. We will continue to identify possible collaborations to solve social challenges on issues of sustainability, health, equity and inclusion. We also want to connect those who are working with data or want to explore that realm with the opportunities offered by the Microsoft Certifications in Data and Artificial Intelligence. And, above all, this issue requires a good regulatory framework and, for this, it is necessary that those who define the policies meet with the industry.

Artificial intelligence is increasingly present in our lives. However, its presence is increasingly subtle and unnoticed. As a technology matures and permeates society, it becomes more and more transparent, until it becomes completely naturalized. Artificial intelligence is rapidly going down this path, and today, we tell you about it with a new example.

Introduction

In this communication and dissemination space we have often talked about artificial intelligence (AI) and its practical applications. On other occasions, we have communicated monographic reports and articles on specific applications of AI in real life. It is clear that this is a highly topical subject with great repercussions in the technology sector, and that is why we continue to focus on our informative work in this field.

On this occasion, we talk about the latest advances in artificial intelligence applied to the field of natural language processing. In early 2020 we published a report in which we cited the work of Paul Daugherty and James Wilson - Human + Machine - to explain the three states in which AI collaborates with human capabilities. Daugherty and Wilson explain these three states of collaboration between machines (AI) and humans as follows (see Figure 1). In the first state, AI is trained with genuinely human characteristics such as leadership, creativity and value judgments. In the opposite state, characteristics where machines demonstrate better performance than humans are highlighted. We are talking about repetitive, precise and continuous activities. However, the most interesting state is the intermediate one. In this state, the authors identify activities or characteristics in which humans and machines perform hybrid activities, in which they complement each other. In this intermediate state, in turn, two stages of maturity are distinguished.

- In the first stage - the most immature - humans complement machines. We have numerous examples of this stage today. Humans teach machines to drive (autonomous cars) or to understand our language (natural language processing).

- The second stage of maturity occurs when AI empowers or amplifies our human capabilities. In the words of Daugherty and Wilson, AI gives us humans superpowers.

Figure 1: States of human-machine collaboration. Original source.

In this post, we show you an example of this superpower returned by AI. The superpower of summarizing books from tens of thousands of words to just a few hundred. The resulting summaries are similar to how a human would do it with the difference that the AI does it in a few seconds. Specifically, we are talking about the latest advances published by the company OpenAI, dedicated to research in artificial intelligence systems.

Summarizing books as a human

OpenAI similarly defines Daugherty and Wilson's reasoning on models of AI collaboration with humans. The authors of the latest OpenAI paper explain that, in order to implement such powerful AI models that solve global and genuinely human problems, we must ensure that AI models act in alignment with human intentions. In fact, this challenge is known as the alignment problem.

The authors explain that: To test scalable alignment techniques, we train a model to summarize entire books [...] Our model works by first summarizing small sections of a book, then summarizing those summaries into a higher-level summary, and so on.

Let's look at an example.

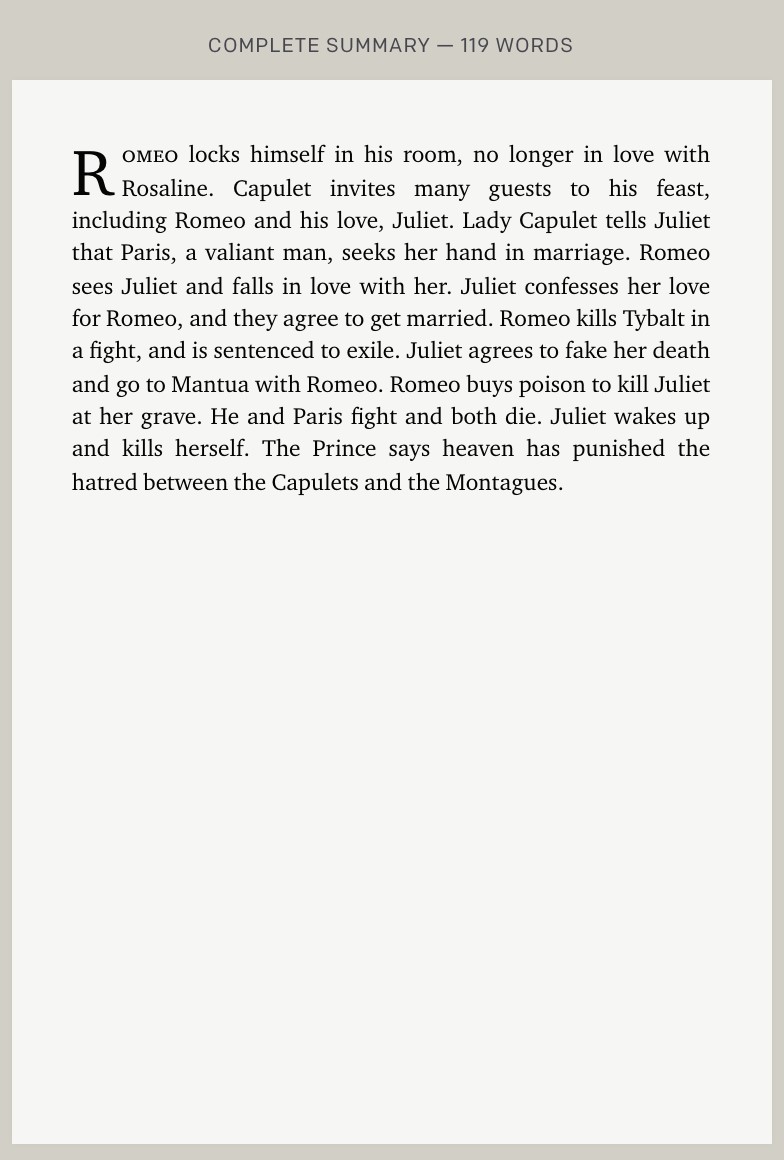

The authors have refined the GPT-3 algorithm to summarize entire books based on an approach known as recursive task decomposition accompanied by reinforcement from human comments. The technique is called recursive decomposition because it is based on making multiple summaries of the complete work (for example, a summary for each chapter or section) and, in subsequent iterations, making, in turn, summaries of the previous summaries, each time with a smaller number of words. The following figure explains the process more visually.

Fuente original: https://openai.com/blog/summarizing-books/

Final result:

Original source: https://openai.com/blog/summarizing-books/

As we have mentioned before, the GPT-3 algorithm has been trained thanks to the set of books digitized under the umbrella of Project Gutenberg. The vast Project Gutenberg repository includes up to 60,000 books in digital format that are currently in the public domain in the United States. Just as Project Gutenberg has been used to train GPT-3 in English, other open data repositories could have been used to train the algorithm in other languages. In our country, the National Library has an open data portal to exploit the available catalog of works under public domain in Spanish.

The authors of the paper state that recursive decomposition has certain advantages over more comprehensive approaches that try to summarize the book in a single step.

- The evaluation of the quality of human summaries is easier when it comes to evaluating summaries of specific parts of a book than when it comes to the entire work.

- A summary always tries to identify the key parts of a book or a chapter of a book, keeping the fundamental data and discarding those that do not contribute to the understanding of the content. Evaluating this process to understand if those fundamental details have really been captured is much easier with this approach based on the decomposition of the text into smaller units.

- This decompositional approach mitigates the limitations that may exist when the works to be summarized are very large.

In addition to the main example we have exposed in this post on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, readers can experience for themselves how this AI works in the openAI summary browser. This website makes available two open repositories of books (classic works) on which one can experience the summarization capabilities of this AI by navigating from the final summary of the book to the previous summaries in the recursive decomposition process.

In conclusion, natural language processing is a key human capability that is being dramatically enhanced by the development of AI in recent years. It is not only OpenAI that is making major contributions in this field. Other technology giants, such as Microsoft and NVIDIA, are also making great strides as evidenced by the latest announcement from these two companies and their new Megatron-Turing NLG model. This new model shows great advances in tasks such as: the generation of predictive text or the understanding of human language for the interpretation of voice commands in personal assistants. With all this, there is no doubt that we will see machines doing incredible things in the coming years.

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, expert in Digital Transformation and Innovation.

The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

A draft Regulation on Artificial Intelligence has recently been made public as part of the European Commission's initiative in this area. It is directly linked to the proposal on data governance, the Directive on the re-use of public sector information and open data, as well as other initiatives in the framework of the European Data Strategy.

This measure is an important step forward in that it means that the European Union will have a uniform regulatory framework that will make it possible to go beyond the individual initiatives adopted by each of the Member States which, as in the case of Spain, have approved their own strategy under a Coordinated Plan that has recently been updated with the aim of promoting the global leadership of the European Union in the commitment to a reliable Artificial Intelligence model.

Why a Regulation?

Unlike the Directive, the EU Regulation is directly applicable in all Member States, and therefore does not need to be transposed through each Member State's own legislation. Although the national strategies served to identify the most relevant sectors and to promote debate and reflection on the priorities and objectives to be considered, the fact is that there was a risk of fragmentation in the regulatory framework given the possibility that each of the States to establish different requirements and guarantees. Ultimately, this potential diversity could negatively affect the legal certainty required by Artificial Intelligence systems and, above all, impede the objective of pursuing a balanced approach that would make the articulation of a reliable regulatory framework possible, based on the fundamental values and rights of the European Union in a global social and technological scenario.

The importance of data

The White Paper on Artificial Intelligence graphically highlighted the importance of data in relation to the viability of this technology by stating categorically that "without data, there is no Artificial Intelligence". This is precisely one of the reasons why a draft Regulation on data governance was promoted at the end of 2020, which, among other measures, attempts to address the main legal challenges that hinder access to and reuse of data.

In this regard, as emphasised in the aforementioned Coordinated Plan, an essential precondition for the proper functioning of Artificial Intelligence systems is the availability of high-quality data, especially in terms of their diversity and respect for fundamental rights. Specifically, based on this elementary premise, it is necessary to ensure that:

- Artificial Intelligence systems are trained on sufficiently large datasets, both in terms of quantity and diversity.

- The datasets to be processed do not generate discriminatory or unlawful situations that may affect rights and freedoms.

- The requirements and conditions of the regulations on personal data protection are considered, not only from the perspective of their strict compliance, but also from the perspective of the principle of proactive responsibility, which requires the ability to demonstrate compliance with the regulations in this area.

The importance of access to and use of high-quality datasets has been particularly emphasised in the draft regulation, in particular with regard to the so-called Common European Data Spaces established by the Commission. The European regulation aims to ensure reliable, responsible and non-discriminatory access to enable, above all, the development of high-risk Artificial Intelligence systems with appropriate safeguards. This premise is particularly important in certain areas such as health, so that the training of AI algorithms can be carried out on the basis of high ethical and legal standards. Ultimately, the aim is to establish optimal conditions in terms of guarantees of privacy, security, transparency and, above all, to ensure adequate institutional governance as a basis for trust in their correct design and operation.

Risk classification at the heart of regulatory obligations

The Regulation is based on the classification of Artificial Intelligence systems considering their level of risk, distinguishing between those that pose an unacceptable risk, those that entail a minimal risk and those that, on the contrary, are considered to be of a high level. Thus, apart from the exceptional prohibition of the former, the draft establishes that those that are classified as high risk must comply with certain specific guarantees, which will be voluntary in the case of system providers that do not have this consideration. What are these guarantees?

- Firstly, it establishes the obligation to implement a data quality management model to be documented in a systematic and orderly manner, one of the main aspects of which refers to data management systems and procedures, including data collection, analysis, filtering, aggregation, labelling.

- Where techniques involving the training of models with data are used, system development is required to take place on the basis of training, validation and test datasets that meet certain quality standards. Specifically, they must be relevant, representative, error-free and complete, taking into account, to the extent required for the intended purpose, the characteristics or elements of the specific geographical, behavioural or functional environment in which the Artificial Intelligence system is intended to be used.

- These include the need for a prior assessment of the availability, quantity and adequacy of the required datasets, as well as an analysis of possible biases and gaps in terms of data gaps, in which case it will be necessary to establish how such gaps can be addressed.

In short, in the event that the Regulation continues to be processed and is finally approved, we will have a regulatory framework at European level which, based on the requirements of respect for rights and freedoms, could contribute to the consolidation and future development of Artificial Intelligence not only from the perspective of industrial competitiveness but also in accordance with legal standards in line with the values and principles on which the European Union is based.

Content prepared by Julián Valero, Professor at the University of Murcia and Coordinator of the Research Group "Innovation, Law and Technology" (iDerTec).

The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Summer is just around the corner and with it the well-deserved holidays. Undoubtedly, this time of year gives us time to rest, reconnect with the family and spend pleasant moments with our friends.

However, it is also a great opportunity to take advantage of and improve our knowledge of data and technology through the courses that different universities make available to us during these dates. Whether you are a student or a working professional, these types of courses can contribute to increase your training and help you gain competitive advantages in the labour market.

Below, we show you some examples of summer courses from Spanish universities on these topics. We have also included some online training, available all year round, which can be an excellent product to learn during the summer season.

Courses related to open data

We begin our compilation with the course 'Big & Open Data. Analysis and programming with R and Python' given by the Complutense University of Madrid. It will be held at the Fundación General UCM from 5 to 23 July, Monday to Friday from 9 am to 2 pm. This course is aimed at university students, teachers, researchers and professionals who wish to broaden and perfect their knowledge of this subject.

Data analysis and visualisation

If you are interested in learning the R language, the University of Santiago de Compostela organises two courses related to this subject, within the framework of its 'Universidade de Verán' The first one is 'Introduction to geographic and cartographic information systems with the R environment', which will be held from 6 to 9 July at the Faculty of Geography and History of Santiago de Compostela. You can consult all the information and the syllabus through this link.

The second is 'Visualisation and analysis of data with R', which will take place from 13 to 23 July at the Faculty of Mathematics of the USC. In this case, the university offers students the possibility of attending in two shifts (morning and afternoon). As you can see in the programme, statistics is one of the key aspects of this training.

If your field is social sciences and you want to learn how to handle data correctly, the course of the International University of Andalusia (UNIA) 'Techniques of data analysis in Humanities and Social Sciences' seeks to approach the use of new statistical and spatial techniques in research in these fields. It will be held from 23 to 26 August in classroom mode.

Big Data

Big Data is increasingly becoming one of the elements that contribute most to the acceleration of digital transformation. If you are interested in this field, you can opt for the course 'Big Data Geolocated: Tools for capture, analysis and visualisation' which will be given by the Complutense University of Madrid from 5 to 23 July from 9 am to 2 pm, in person at the Fundación General UCM.

Another option is the course 'Big Data: technological foundations and practical applications' organised by the University of Alicante, which will be held online from 19 to 23 July.

Artificial intelligence

The Government has recently launched the online course 'Elements of AI' in Spanish with the aim of promoting and improving the training of citizens in artificial intelligence. The Secretary of State for Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence will implement this project in collaboration with the UNED, which will provide the technical and academic support for this training. Elements of AI is a massive open educational project (MOOC) that aims to bring citizens knowledge and skills on Artificial Intelligence and its various applications. You can find out all the information about this course here. And if you want to start the training now, you can register through this link. The course is free of charge.

Another interesting training related to this field is the course 'Practical introduction to artificial intelligence and deep learning' organised by the International University of Andalusia (UNIA). It will be taught in person at the Antonio Machado headquarters in Baeza between 17 and 20 August 2021. Among its objectives, it offers students an overview of data processing models based on artificial intelligence and deep learning techniques, among others.

These are just a few examples of courses that are currently open for enrolment, although there are many more, as the offer is wide and varied. In addition, it should be remembered that summer has not yet begun and that new data-related courses could appear in the coming weeks. If you know of any other course that might be of interest, do not hesitate to leave us a comment below or write to us at contacto@datos.gob.es.

Artificial intelligence is transforming companies, with supply chain processes being one of the areas that is obtaining the greatest benefit. Its management involves all resource management activities, including the acquisition of materials, manufacturing, storage and transportation from origin to final destination.

In recent years, business systems have been modernized and are now supported by increasingly ubiquitous computer networks. Within these networks, sensors, machines, systems, vehicles, smart devices and people are interconnected and continuously generating information. To this must be added the increase in computational capacity, which allows us to process these large amounts of data generated quickly and efficiently. All these advances have contributed to stimulating the application of Artificial Intelligence technologies that offer a sea of possibilities.

In this article we are going to review some Artificial Intelligence applications at different points in the supply chain.

Technological implementations in the different phases of the supply chain

Planning

According Gartner, volatility in demand is one of the aspects that most concern entrepreneurs. The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the weakness in planning capacity within the supply chain. In order to properly organize production, it is necessary to know the needs of the customers. This can be done through techniques of predictive analytics that allow us to predict demand, that is, estimate a probable future request for a product or service. This process also serves as the starting point for many other activities, such as warehousing, shipping, product pricing, purchasing raw materials, production planning, and other processes that aim to meet demand.

Access to real-time data allows the development of Artificial Intelligence models that take advantage of all the contextual information to obtain more precise results, reducing the error significantly compared to more traditional forecasting methods such as ARIMA or exponential smoothing.

Production planning is also a recurring problem where variables of various kinds play an important role. Artificial intelligence systems can handle information involving material resources; the availability of human resources (taking into account shifts, vacations, leave or assignments to other projects) and their skills; the available machines and their maintenance and information on the manufacturing process and its dependencies to optimize production planning in order to satisfactorily meet the objectives.

Production

Within of the stages of the production process, one of the stages more driven by the application of artificial intelligence is the quality control and, more specifically, the detection of defects. According to European Comission, 50% of the production can end up as scrap due to defects, while, in complex manufacturing lines, the percentage can rise to 90%. On the other hand, non-automated quality control is an expensive process, as people need to be trained to be able to perform the inspections properly and, furthermore, these manual inspections could cause bottlenecks in the production line, delaying delivery times. Coupled with this, inspectors do not increase in number as production increases.

In this scenario, the application of computer vision algorithms can solve all these problems. These systems learn from defect examples and can thus extract common patterns to be able to classify future production defects. The advantages of these systems is that they can achieve the precision of a human or even better, since they can process thousands of images in a very short time and are scalable.

On the other hand, it is very important to ensure the reliability of the machinery and reduce the chances of production stoppage due to breakdowns. In this sense, many companies are betting on predictive maintenance systems that are capable of analyzing monitoring data to assess the condition of the machinery and schedule maintenance if necessary.

Open data can help when training these algorithms. As an example, the Nasa offers a collection of data sets donated by various universities, agencies or companies useful for the development of prediction algorithms. These are mostly time series of data from a normal operating state to a failed state. This article shows how one of these specific data sets (Turbofan Engine Degradation Simulation Data Set, which includes sensor data from 100 engines of the same model) can be taken to perform a exploratory analysis and a model of linear regression reference.

Transport

Route optimization is one of the most critical elements in transportation planning and business logistics in general. Optimal planning ensures that the load arrives on time, reducing cost and energy to a minimum. There are many variables that intervene in the process, such as work peaks, traffic incidents, weather conditions, etc. And that's where artificial intelligence comes into play. A route optimizer based on artificial intelligence is able to combine all this information to offer the best possible route or modify it in real time depending on the incidents that occur during the journey.

Logistics organizations use transport data and official maps to optimize routes in all modes of transport, avoiding areas with high congestion, improving efficiency and safety. According to the study “Open Data impact Map”, The open data most demanded by these companies are those directly related to the means of transport (routes, public transport schedules, number of accidents…), but also geospatial data, which allow them to better plan their trips.

In addition, exist companies that share their data in B2B models. As stated in the Cotec Foundation report “Guide for opening and sharing data in the business environment”, The Spanish company Primafrio, shares data with its customers as an element of value in their operations for the location and positioning of the fleet and products (real-time data that can be useful to the customer, such as the truck license plate, position, driver , etc.) and for billing or accounting tasks. As a result, your customers have optimized order tracking and their ability to advance billing.

Closing the transport section, uOne of the objectives of companies in the logistics sector is to ensure that goods reach their destination in optimal conditions. This is especially critical when working with companies in the food industry. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor the state of the cargo during transport. Controlling variables such as temperature, location or detecting impacts is crucial to know how and when the load deteriorated and, thus, be able to take the necessary corrective actions to avoid future problems. Technologies such as IoT, Blockchain and Artificial Intelligence are already being applied to these types of solutions, sometimes including the use of open data.

Customer service

Offering good customer service is essential for any company. The implementation of conversational assistants allows to enrich the customer experience. These assistants allow users to interact with computer applications conversationally, through text, graphics or voice. By means of speech recognition techniques and natural language processing, these systems are capable of interpreting the intention of users and taking the necessary actions to respond to their requests. In this way, users could interact with the wizard to track their shipment, modify or place an order. In the training of these conversational assistants it is necessary to use quality data, to achieve an optimal result.

In this article we have seen only some of the applications of artificial intelligence to different phases of the supply chain, but its capacity is not only limited to these. There are other applications such as automated storage used by Amazon at its facilities, dynamic prices depending on the demand or the application of artificial intelligence in marketing, which only give an idea of how artificial intelligence is revolutionizing consumption and society.

Content elaborated by Jose Antonio Sanchez, expert in Data Science and enthusiast of the Artificial Intelligence.

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

It has been a long time since that famous article entitled “Data Scientist: The Sexiest Job of the 21st Century” was published in 2012. Since then, the field of data science has become highly professionalised. A multitude of techniques, frameworks and tools have been developed that accelerate the process of turning raw data into valuable information. One of these techniques is known as Auto ML or Automatic Machine Learning. In this article we will review the advantages and characteristics of this method.

In a data science process, any data scientist usually uses a systematic working method, whereby raw data is distilled until information of value to the business from which the data is derived is extracted. There are several definitions of the data analysis process, although they are all very similar with minor variations. The following figure shows an example of a data analysis process or workflow.

As we can see, we can distinguish three stages:

- Importing and cleaning.

- Scanning and modelling.

- Communication.

Depending on the type of source data and the result we seek to achieve with this data, the modelling process may vary. However, regardless of the model, the data scientist must be able to obtain a clean dataset ready to serve as input to the model. In this post we will focus on the second stage: exploration and modelling.

Once this clean and error-free data has been obtained (after import and cleaning in step 1), the data scientist must decide which transformations to apply to the data, with the aim of making some data derived from the originals (in conjunction with the originals), the best indicators of the model underlying the dataset. We call these transformations features.

The next step is to divide our dataset into two parts: one part, for example 60% of the total dataset, will serve as the training dataset. The remaining 40% will be reserved for applying our model, once it has been trained. We call this second part the test subset. This process of splitting the source data is done with the intention of assessing the reliability of the model before applying it to new data unknown to the model. An iterative process now unfolds in which the data scientist tests various types of models that he/she believes may work on this dataset. Each time he/she applies a model, he/she observes and measures the mathematical parameters (such as accuracy and reproducibility) that express how well the model is able to reproduce the test data. In addition to testing different types of models, the data scientist may vary the training dataset with new transformations, calculating new and different features, in order to come up with some features that make the model in question fit the data better.

We can imagine that this process, repeated dozens or hundreds of times, is a major consumer of both human and computational resources. The data scientist tries to perform different combinations of algorithms, models, features and percentages of data, based on his or her experience and skill with the tools. However, what if it were a system that would perform all these combinations for us and finally come up with the best combination? Auto ML systems have been created precisely to answer this question.

In my opinion, an Auto ML system or tool is not intended to replace the data scientist, but to complement him or her, helping the data scientist to save a lot of time in the iterative process of trying different techniques and data to reach the best model. Generally speaking, we could say that an Auto ML system has (or should have) the following benefits for the data scientist:

- Suggest the best Machine Learning techniques and automatically generate optimised models (automatically adjusting parameters), having tested a large number of training and test datasets respectively.

- Inform the data scientist of those features (remembering that they are transformations of the original data) that have the greatest impact on the final result of the model.

- Generate visualisations that allow the data scientist to understand the outcome of the process carried out by Auto ML. That is, to teach the Auto ML user the key indicators of the outcome of the process.

- Generate an interactive simulation environment that allows users to quickly explore the model to see how it works.

Finally, we mention some of the best-known Auto ML systems and tools, such as H2O.ai, Auto-Sklearn end TPOT. It should be noted that these three systems cover the entire Machine Learning process that we saw at the beginning. However, there are more solutions and tools that partially cover some of the steps of the complete process. There are also articles comparing the effectiveness of these systems for certain machine learning problems on open and accessible datasets.

In conclusion, these tools provide valuable solutions to common data science problems and have the potential to dramatically improve the productivity of data science teams. However, data science still has a significant art component and not all problems are solved with automation tools. We encourage all algorithm alchemists and data craftsmen to continue to devote time and effort to developing new techniques and algorithms that allow us to turn data into value quickly and effectively.

The aim of this post is to explain to the general public, in a simple and accessible way, how auto ML techniques can simplify the process of advanced data analysis. Sometimes oversimplifications may be used in order not to overcomplicate the content of this post.

Content elaborated by Alejandro Alija, expert in Digital Transformation and Innovation.

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

A few weeks ago, we told you about the different types of machine learning through a series of examples, and we analysed how to choose one or the other based on our objectives and the datasets available to train the algorithm.

Now let's assume that we have an already labelled dataset and we need to train a supervised learning model to solve the task at hand. At this point, we need some mechanism to tell us whether the model has learned correctly or not. That is what we are going to discuss in this post, the most used metrics to evaluate the quality of our models.

Model evaluation is a very important step in the development methodology of machine learning systems. It helps to measure the performance of the model, that is, to quantify the quality of the predictions it offers. To do this, we use evaluation metrics, which depend on the learning task we apply. As we saw in the previous post, within supervised learning there are two types of tasks that differ, mainly, in the type of output they offer:

- Classification tasks, which produce as output a discrete label, i.e. when the output is one within a finite set.

- Regression tasks, which output a continuous real value.

Here are some of the most commonly used metrics to assess the performance of both types of tasks:

Evaluation of classification models

In order to better understand these metrics, we will use as an example the predictions of a classification model to detect COVID patients. In the following table we can see in the first column the example identifier, in the second column the class predicted by the model, in the third column the actual class and the fourth column indicates whether the model has failed in its prediction or not. In this case, the positive class is "Yes" and the negative class is "No".

Examples of evaluation metrics for classification model include the following:

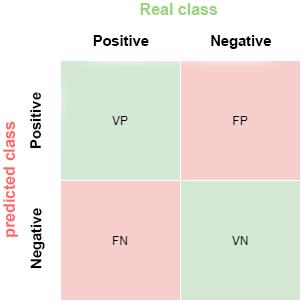

- Confusion matrix: this is a widely used tool that allows us to visually inspect and evaluate the predictions of our model. Each row represents the number of predictions of each class and the columns represent the instances of the actual class.

The description of each element of the matrix is as follows:

True Positive (VP): number of positive examples that the model predicts as positive. In the example above, VP is 1 (from example 6).

False positive (FP): number of negative examples that the model predicts as positive. In our example, FP is equal to 1 (from example 4).

False negative (FN): number of positive examples that the model predicts as negative. FN in the example would be 0.

True negative (VN): number of negative examples that the model predicts as negative. In the example, VN is 8.

- Accuracy: the fraction of predictions that the model made correctly. It is represented as a percentage or a value between 0 and 1. It is a good metric when we have a balanced dataset, that is, when the number of labels of each class is similar. The accuracy of our example model is 0.9, since it got 9 predictions out of 10 correct. If our model had always predicted the "No" label, the accuracy would be 0.9 as well, but it does not solve our problem of identifying COVID patients.

- Recall: indicates the proportion of positive examples that are correctly identified by the model out of all actual positives. That is, VP / (VP + FN). In our example, the sensitivity value would be 1 / (1 + 0) = 1. If we were to evaluate with this metric, a model that always predicts the positive label ("Yes") would have a sensitivity of 1, but it would not be a very intelligent model. Although the ideal for our COVID detection model is to maximise sensitivity, this metric alone does not ensure that we have a good model.

- Precision: this metric is determined by the fraction of items correctly classified as positive among all items that the model has classified as positive. The formula is VP / (VP + FP). The example model would have an accuracy of 1 / (1 + 1) = 0.5. Let us now return to the model that always predicts the positive label. In that case, the accuracy of the model is 1 / (1 + 9) = 0.1. We see how this model had a maximum sensitivity, but has a very poor accuracy. In this case we need both metrics to evaluate the real quality of the model.

- F1 score: combines the Precision and Recall metrics to give a single score. This metric is the most appropriate when we have unbalanced datasets. It is calculated as the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. The formula is F1 = (2 * precision * recall) / (precision + recall). You may wonder why we use the harmonic mean and not the simple mean. This is because the harmonic mean means that if one of the two measurements is small (even if the other is maximum), the value of F1 score is going to be small.

Evaluation of regression models

Unlike classification models, in regression models it is almost impossible to predict the exact value, but rather to be as close as possible to the real value, so most metrics, with subtle differences between them, are going to focus on measuring that: how close (or far) the predictions are from the real values.

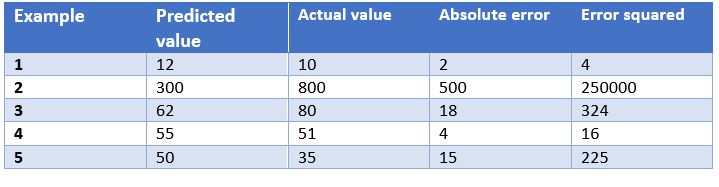

In this case, we have as an example the predictions of a model that determines the price of watches depending on their characteristics. In the table we show the price predicted by the model, the actual price, the absolute error and the squared error.

Some of the most common evaluation metrics for regression models are:

- Mean Absolute Error: This is the mean of the absolute differences between the target and predicted values. Since it is not squared, it does not penalise large errors, which makes it not very sensitive to outliers, so it is not a recommended metric in models where attention must be paid to outliers. This metric also represents the error on the same scale as the actual values. Ideally, its value should be close to zero. For our watch pricing model, the mean absolute error is 107.8.

- Mean Squared Errors: One of the most commonly used measures in regression work. It is simply the mean of the differences between the target and the predicted value squared. By squaring the errors, it magnifies large errors, so use it with care when we have outliers in our data set. It can take values between 0 and infinity. The closer the metric is to zero, the better. The mean square error of the example model is 50113.8. We see how in the case of our example large errors are magnified.

- Root Mean Squared Srror: This is equal to the square root of the previous metric. The advantage of this metric is that it presents the error in the same units as the target variable, which makes it easier to understand. For our model this error is equal to 223.86.

- R-squared: also called the coefficient of determination. This metric differs from the previous ones, as it compares our model with a basic model that always returns as prediction the mean of the training target values. The comparison between these two models is made on the basis of the mean squared errors of each model. The values this metric can take range from minus infinity to 1. The closer the value of this metric is to 1, the better our model is. The R-squared value for the model will be 0.455.

- Adjusted R-squared. An improvement of R-squared. The problem with the previous metric is that every time more independent variables (or predictor variables) are added to the model, R-squared stays the same or improves, but never gets worse, which can be confusing, because just because one model uses more predictor variables than another, it does not mean that it is better. Adjusted R-squared compensates for the addition of independent variables. The adjusted R-squared value will always be less than or equal to the R-squared value, but this metric will show improvement when the model is actually better. For this measure we cannot do the calculation for our example model because, as we have seen before, it depends on the number of examples and the number of variables used to train such a model.

Conclusion

When working with supervised learning algorithms it is very important to choose a correct evaluation metric for our model. For classification models it is very important to pay attention to the dataset and check whether it is balanced or not. For regression models we have to consider outliers and whether we want to penalise large errors or not.

Generally, however, the business domain will guide us in the right choice of metric. For a disease detection model, such as the one we have seen, we are interested in high sensitivity, but we are also interested in a good accuracy value, so F1-score would be a smart choice. On the other hand, in a model to predict the demand for a product (and therefore production), where overstocking may incur a storage cost overrun, it may be a good idea to use the mean squared errors to penalise large errors.

Content elaborated by Jose Antonio Sanchez, expert in Data Science and enthusiast of the Artificial Intelligence.

Contents and points of view expressed in this publication are the exclusive responsibility of its author.

2020 is coming to an end and in this unusual year we are going to have to experience a different, calmer Christmas with our closest nucleus. What better way to enjoy those moments of calm than to train and improve your knowledge of data and new technologies?

Whether you are looking for a reading that will make you improve your professional profile to which to dedicate your free time on these special dates, or if you want to offer your loved ones an educational and interesting gift, from datos.gob.es we want to propose some book recommendations on data and disruptive technologies that we hope will be of interest to you. We have selected books in Spanish and English, so that you can also put your knowledge of this language into practice.

Take note because you still have time to include one in your letter to Santa Claus!

INTELIGENCIA ARTIFICIAL, naturalmente. Nuria Oliver, ONTSI, red.es (2020)

What is it about?: This book is the first of the new collection published by the ONTSI called “Pensamiento para la sociedad digital”. Its pages offer a brief journey through the history of artificial intelligence, describing its impact today and addressing the challenges it presents from various points of view.

Who is it for?: It is aimed especially at decision makers, professionals from the public and private sector, university professors and students, third sector organizations, researchers and the media, but it is also a good option for readers who want to introduce themselves and get closer to the complex world of artificial intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, Stuart Russell

What is it about?: Interesting manual that introduces the reader to the field of Artificial Intelligence through an orderly structure and understandable writing.

Who is it for?: This textbook is a good option to use as documentation and reference in different courses and studies in Artificial Intelligence at different levels. For those who want to become experts in the field.

Situating Open Data: Global Trends in Local Contexts, Danny Lämmerhirt, Ana Brandusescu, Natalia Domagala – African Minds (October 2020)

What is it about?: This book provides several empirical accounts of open data practices, the local implementation of global initiatives, and the development of new open data ecosystems.

Who is it for?: It will be of great interest to researchers and advocates of open data and to those in or advising government administrations in the design and implementation of effective open data initiatives. You can download its PDF version through this link.

The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, Second Edition (Springer Series in Statistics), Trevor Hustle, Jerome Friedman. – Springer (May 2017)

What is it about?: This book describes various statistical concepts in a variety of fields such as medicine, biology, finance, and marketing in a common conceptual framework. While the focus is statistical, the emphasis is on definitions rather than mathematics.

Who is it for?: It is a valuable resource for statisticians and anyone interested in data mining in science or industry. You can also download its digital version here.

Europa frente a EEUU y China: Prevenir el declive en la era de la inteligencia artificial, Luis Moreno, Andrés Pedreño – Kdp (2020)

What is it about?: This interesting book addresses the reasons for the European delay with respect to the power that the US and China do have, and its consequences, but above all it proposes solutions to the problem that is exposed in the work.

Who is it for?: It is a reflection for those interested in thinking about the change that Europe would need, in the words of its author, "increasingly removed from the revolution imposed by the new technological paradigm".

What is it about?: This book calls attention to the problems that can lead to the misuse of algorithms and proposes some ideas to avoid making mistakes.

Who is it for?: These pages do not appear overly technical concepts, nor are there formulas or complex explanations, although they do deal with dense problems that need the author's attention.

Data Feminism (Strong Ideas), Catherine D’Ignazio, Lauren F. Klein. MIT Press (2020)

What is it about?: These pages address a new way of thinking about data science and its ethics based on the ideas of feminist thought.

Who is it for?: To all those who are interested in reflecting on the biases built into the algorithms of the digital tools that we use in all areas of life.

Open Cities | Open Data: Collaborative Cities in the Information, Scott Hawken, Hoon Han, Chris Pettit – Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore (2020)

What is it about?: This book explains the importance of opening data in cities through a variety of critical perspectives, and presents strategies, tools, and use cases that facilitate both data openness and reuse..

Who is it for?: Perfect for those integrated in the data value chain in cities and those who have to develop open data strategies within the framework of a smart city, but also for citizens concerned about privacy and who want to know what happens - and what can happen- with the data generated by cities.

Although we would love to include them all on this list, there are many interesting books on data and technology that fill the shelves of hundreds of bookstores and online stores. If you have any extra recommendations that you want to make us, do not hesitate to leave us your favorite title in comments. The members of the datos.gob.es team will be delighted to read your recommendations this Christmas.

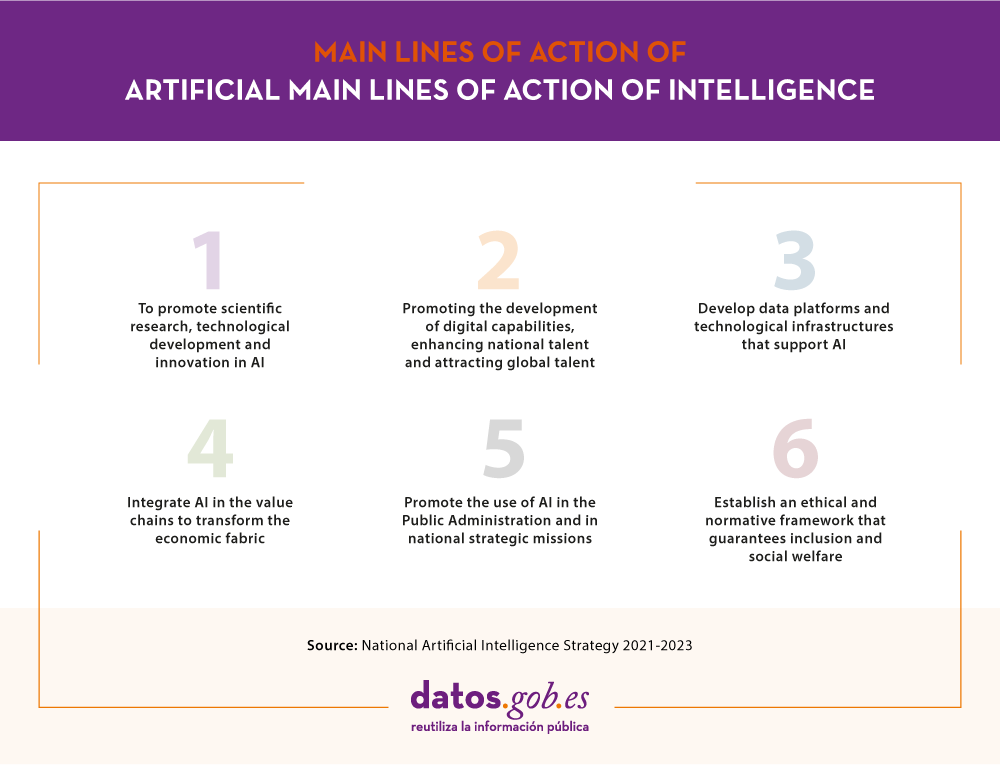

Spain already has a new National Artificial Intelligence Strategy. The document, which includes 600 million euros for measures related to artificial intelligence (AI), was presented on December 2 at the Palacio de la Moncloa.

The National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence (known as ENIA) is component 16 of the Plan for the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience of the Spanish economy, and one of the fundamental proposals of the Digital Spain Agenda 2025 in its line 9 of action, which highlights AI as a key element for boosting the growth of our economy in the coming years. In addition, the new strategy is aligned with the European action plans developed in this area, and especially with the White Paper on Artificial Intelligence.

Objectives and lines of action

The ENIA is a dynamic and flexible framework, open to the contribution of companies, citizens, social agents and the rest of the administrations, which was created with 7 objectives: scientific excellence and innovation, the projection of the Spanish language, the creation of qualified employment, the transformation of the Spanish productive fabric, the creation of an environment of trust in relation to AI and the promotion of an inclusive and sustainable AI that takes into account humanist values.

To achieve these objectives, 6 lines of action have been created, which bring together a total of 30 measures to be developed in the period 2020-2025:

In short, the aim is to create a national ecosystem of innovative, competitive and ethical artificial intelligence. And to do this, it is essential to have large volumes of quality and interoperable data and metadata, which are accessible, complete, secure and respectful of privacy.

Open data in the National Strategy of Artificial Intelligence

The availability of open data is essential for the proper functioning of artificial intelligence, since the algorithms must be fed and trained by data whose quality and availability allows continuous improvement. In this way we can create value services that impact on the improvement of society and the economy.

The National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence highlights how, thanks to the various initiatives undertaken in recent years, Spain has become a European benchmark for open data, highlighting the role of the Aporta Initiative in promoting the openness and reuse of public information.

In strategic axis 3 of the document, several key areas are highlighted where to act linked to AI data platforms and technological infrastructures:

- Developing the regulatory framework for open data, to define a strategy for publication and access to public data from administrations in multilingual formats, and to ensure the correct and safe use of the data.

- Promote actions in the field of data platforms, models, algorithms, inference engines and cyber security, with the focus on boosting research and innovation. Reference is made to the need to promote Digital Enabling Technologies such as connectivity infrastructures, massive data environments (cloud) or process automation and control, paying special attention to Strategic Supercomputing Capabilities (HPC).

- Promote the specific development of AI technologies in the field of natural language processing, promoting the use of Spanish in the world. In this sense, the National Plan of Language Technologies will be promoted and the LEIA project, developed by the Royal Spanish Academy for the defense, projection and good use of the Spanish language in the digital universe, will be supported.

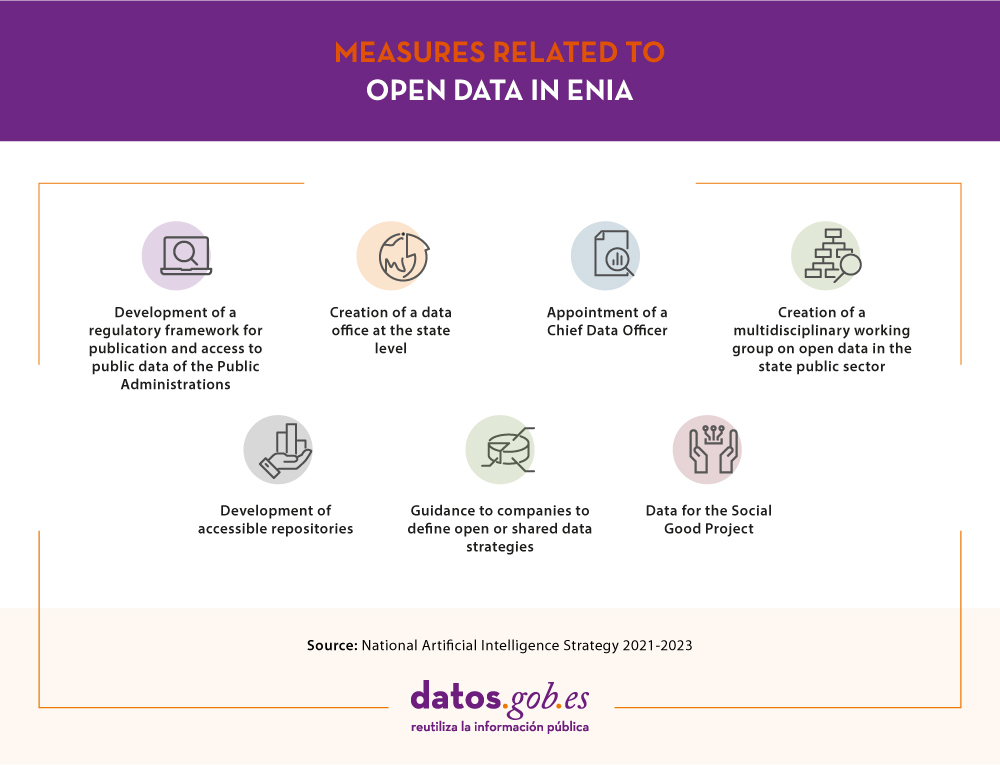

In the specific case of open data, one of the first measures highlighted is the creation of the Data Office at the state level that will coordinate all public administrations in order to homogenize the storage, access and processing of data. To strengthen this action, a Chief Data Officer will be appointed. In addition, a multidisciplinary working group on open data in the state public sector will be set up to highlight the efforts that have been made in the field of data in Spain and to continue promoting the openness and reuse of public sector information.

The strategy also considers the private sector, and highlights the need to promote the development of accessible repositories and to guide companies in the definition of open or shared data strategies. In this sense, shared spaces of sectorial and industrial data will be created, which will facilitate the creation of AI applications. Furthermore, mention is made of the need to offer data disaggregated by sex, age, nationality and territory, in such a way as to eliminate biases linked to these aspects.

In order to stimulate the use and governance of public and citizen data, the creation of the Data for Social Welfare Project is established as an objective, where open and citizen-generated data will play a key role in promoting accountability and public participation in government.

Other highlights of the ENIA

In addition to actions related to open data, the National Strategy of Artificial Intelligence includes more transversal actions, for example:

- The incorporation of AI in the public administration will be promoted, improving from transparency and effective decision-making to productivity and quality of service (making management and the relationship with citizens more efficient). Here the Aporta Initiative has been playing a key role with its support to public sector bodies in the publication of quality data and the promotion of its reuse. Open data repositories will be created to allow optimal access to the information needed to develop new services and applications for the public and private sectors. In this sense, an innovation laboratory (GobTechLab) will be created and training programs will be carried out.

- The aim is to promote scientific research through the creation of a Spanish Network of Excellence in AI with research and training programs and the setting up of new technological development centers. Special attention will be given to closing the gender gap.

- A program of aid to companies for the development of AI and data solutions will be launched, and the network of Digital innovation Hubs will be reinforced. A NextTech Fund for public-private venture capital will be created.

- Talent will be promoted through the National Digital Skills Plan. AI-related elements will be introduced in schools and the university and professional AI training offer will be boosted. The SpAIn Talent Hub program will be developed in coordination with ICEX Invest to attract foreign investment and talent.

- A novelty of the strategy is that it takes into account ethical and social regulation to fight discrimination. Observatories for ethical and legal evaluation of algorithmic systems will be created and the Digital Rights Charter, currently under revision, will be developed.

In short, we are facing a necessary strategy to boost the growth of AI in Spain, promoting our society and economy, and improving our international competitiveness.