Madrid City Council has launched an initiative to demonstrate the potential of open data: the first edition of the Open Data Reuse Awards 2025. With a total budget of 15,000 euros, this competition seeks to promote the reuse of the data shared by the council on its open data portal, demonstrating that they can be a driver of social innovation and citizen participation.

The challenge is clear: to turn data into useful, original and impactful ideas. If you think you can do it, below, we summarize the information you must consider to compete.

Who can participate?

The competition is open to practically everyone: from individuals to companies or groups of any kind. The only condition is to submit a project carried out between September 10, 2022 and September 9, 2025 and that uses at least one dataset from the Madrid City Council's open data portal as a base. Data from other public and private sources can also be used, as long as the Madrid City Council datasets are a key part of the project.

Of course, projects that have already been awarded, contracted or financed by the City Council itself are not accepted, nor are works submitted after the deadline or without the required documentation.

What projects can be submitted?

There are four main areas in which you can participate:

- Web services and applications: refers to projects that provide services, studios, web applications, or mobile apps.

- Studies, research and ideas: refers to projects of exploration, analysis or description of ideas aimed at the creation of services, studies, visualizations, web applications or mobile apps. Bachelor's and master's degree final university projects can also participate in this category.

- Proposals to improve the quality of the open data portal: includes projects, services, applications or initiatives that contribute to boosting the quality of the datasets published on the Madrid City Council's open data portal.

- Data visualizations: you can participate in this category with various content, such as maps, graphs, tables, 3D models, digital art, web applications and animations. Representations can be static, such as infographics, posters, or figures in publications, or dynamic, including videos, interactive dashboards, and stories.

What are the prizes?

For each category, two prizes for different economic endowments are awarded:

|

Category |

First prize |

Second prize |

|

Web services and applications |

3.000 € | 1.500 € |

| Proposals to improve the quality of the open data portal | 3.000 € | 1.500 € |

| Studies, research and ideas | 2.000 € | 1.000 € |

| Data visualizations | 2.000 € | 1.000 € |

Figure 1. Prize money for the first edition of the 2025 Open Data Reuse Awards. Source: Madrid City Council.

Beyond the economic prize, this call is a great opportunity to give visibility to ideas that take advantage of the transparency and potential of open data. In addition, if the proposal improves public services, solves a real problem or helps to better understand the city, it will have great value that goes far beyond recognition.

How are projects valued?

A jury will evaluate each project by assigning a maximum score of 50 points, which will take into account aspects such as originality, social benefit, technical quality, accessibility, ease of use, or even design, in the case of visualizations. If deemed necessary, the jury may request further information submitted to the participants.

The two projects with the highest score will win, although to be considered, the proposals must reach at least 25 points out of a possible 50. If none of them meets this requirement, the category will be declared void.

The jury will be made up of representatives from different areas of the City Council, with experience in innovation, transparency, technology and data. A representative of ASEDIE (Multisectoral Association of Information), the association that promotes the reuse and distribution of information in Spain, will also participate.

How do I participate?

The deadline to register is September 9, 2025 at 11:59 p.m. In the case of natural people, the application can be submitted:

- Online through the City Council's Electronic Office. This procedure requires identification and electronic signature.

- In person at municipal service offices.

In the case of legal people, they may only submit their candidacy electronically.

In any case, the official form must be completed and accompanied by a report explaining the project, its operation, its benefits, the use of the data, and if possible, including screenshots, links or prototypes.

You can see the complete rules here.

More than 90,000 people from all over the world participated in the latest edition of the Space App Challenge. This annual two-day event, organized by the US space agency, NASA, is an opportunity to innovate and learn about the advantages that open space data can offer.

This year the competition will be held on October 4 and 5. Through a hackathon, participants will engage first-hand with NASA's most relevant missions and research. It's an opportunity to learn how to launch and lead projects through hands-on use of NASA data in the real world. In addition, it is a free activity open to anyone (those under 18 years of age must be accompanied by a legal guardian).

In this post, we tell you some of the keys you need to know about this global benchmark event.

Where is it held?

Under the banner of the Space Apps Challenge, virtual and face-to-face events take place all over the world. Specifically, in Spain, meetings are held in several cities:

- Barcelona

- Where: in person, at 42 Barcelona (Carrer D'Albert Einstein 11).

- Madrid

- Where: face-to-face, at the School of Digital Competences – San Blas Digital (Calle Amposta, 34).

- Murcia

- Where: in person at UCAM HITECH (Av. Andrés Hernandez Ros, 1, Guadalupe).

- Malaga

- Where: Face-to-face, at a location to be determined (you can contact the event organizer through the link).

- Pamplona

- Where: face-to-face and virtual, in a location to be determined (you can contact the event organization through the link)

- San Vicente del Raspeig (Alicante)

- Where: in person, at the Alicante Science Park (University of Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig).

- Seville

- Where: Face-to-face, at a location yet to be determined (you can contact the event organizer via the link).

- Valencia

- Where: in person, at the UPV Student House, Polytechnic University of Valencia (Camino de Vera, s/n Building 4K).

- Zaragoza

- Where: in person, at the Betancourt Building, Río Ebro Campus (EINA) Calle María de Luna, 1.

All of them will have a welcome ceremony on Friday, October 3 at 5:30 p.m . in which the details of the competition will be presented, the teams and the themes of each challenge will be organized.

To participate in any of the events, you can register individually and the organization will help you find a team. You can also register your team directly (of a maximum of 6 people).

If you can't find any in-person events near you, you can sign up for the universal event that will be online.

Are there any prizes?

Yes! Each event will award its own prizes. In addition, NASA recognizes, each year, ten global awards divided into different categories:

-

Best Use of Science Award: recognizes the project that makes the most valid and outstanding use of science and/or the scientific method.

-

Best Data Use Award: awarded to the project that makes spatial data more accessible or uses it in a unique way.

-

Best Use of Technology Award: distinguishes the project that represents the most innovative use of technology.

-

Galactic Impact Award: awarded to the project with the greatest potential to improve life on Earth or in the universe.

-

Best Mission Concept Award: recognizes the project with the most plausible concept and design.

-

Most Inspiring Award: It is awarded to the project that manages to move and inspire the public.

-

Best Narrative Award: Highlights the project that most creatively communicates the potential of open data through the art of storytelling.

-

Global Connection Award: awarded to the project that best connects people around the world through technology.

-

Art and Technology Award: recognizes the project that most effectively combines technical and creative skills.

- Local Impact Award: awarded to the project that demonstrates the greatest potential to generate impact at the local level.

Figure 1. Space App Challenge Awards. Source: https://www.spaceappschallenge.org/brand/

From Gijón to the world: the Spanish project awarded in 2024

In last year's edition, a Spanish project, specifically from Gijón, won the global award for best mission concept with its Landsat Connect application proposal. The AsturExplorer team developed a web application designed to provide a fast, simple and intuitive way to track the path of Landsat satellites and access surface reflectance data. Their project fostered interdisciplinary and scientific learning capacities, and empowered citizens.

The Landsat program consists of a series of Earth observation satellite missions, jointly managed by NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), providing images and data about our planet since 1972.

End users of the app developed by AsturExplorer can set a destination location and receive notifications in advance to know when the Landsat satellite will pass over each area. This allows users to prepare and take their own measurements on the ground and obtain pixel data without the need to constantly monitor satellite schedules.

The AsturExplorer team used open Landsat data from NASA and Earth Explorer. They also made use of artificial intelligence to understand the technical problem and compare multiple alternatives. You can read more about this use case here.

How do I register?

The Space App Challenge website offers a section of frequently asked questions and a video tutorial to facilitate registration. The process is simple:

- Create an account

- Register for the Hackathon

- Choose a local event

- Join a team and form your own

- Submit a project (before 11.59am on 5 October)

- Complete the Engagement Survey

We encourage you to be part of this global benchmark event where you will reuse open datasets. A great opportunity!

Between ice cream and longer days, summer is here. At this time of year, open information can become our best ally to plan getaways, know schedules of the bathing areas in our community or even know the state of traffic on roads that take us to our next destination.

Whether you're on the move or at home resting, you can find a wide variety of datasets and apps on the datos.gob.es portal that can transform the way you live and enjoy the summer. In addition, if you want to take advantage of the summer season to train, we also have resources for you.

Training, rest or adventure, in this post, we offer you some of the resources that can be useful this summer.

An opportunity to learn: courses and cultural applications

Are you thinking of making a change in your professional career? Or would you like to improve in a discipline? Data science is one of the most in-demand skills for companies and artificial intelligence offers new opportunities every day to apply it in our day-to-day lives.

To understand both disciplines well and be up to date with their development, you can take advantage of the summer to train in programming, data visualization or even generative AI. In this post, which we published at the beginning of summer, you have a list of proposals, you are still in time to sign up for some!

If you already have some knowledge, we advise you to review our step-by-step exercises. In each of them you will find the code reproducible and fully documented, so you can replicate it at your own pace. In this infographic we show you several examples, divided by themes and level of difficulty. A practical way to test your technical skills and learn about innovative tools and technologies.

If instead of data science, you want to take advantage of it to gain more cultural knowledge, we also have options for you. First of all, we recommend this dataset on the cultural agenda of events in the Basque Country to discover festivals, concerts and other cultural activities. Another interesting dataset is that of tourist information offices in Tenerife where they will inform you how to plan cultural itineraries. And this application will accompany you on a tour of Castilla y León through a gamified map to identify tourist places of interest.

Plan your perfect getaway: datasets for tourism and vacations

Some of the open datasets you can find on datos.gob.es are the basis for creating applications that can be very useful for travel. We are talking, for example, about the dataset of campsites in Navarre that provides updated data on active tourism camps, including information on services, location and capacity. In this same autonomous community, this dataset on restaurants and cafeterias may be useful to you.

On the other hand, this dataset on the supply of tourist accommodation in Aragon presents a complete catalogue of hotels, inns and hostels classified by category, allowing travellers to make informed decisions according to their budget and preferences.

Another interesting resource is this dataset published by the National Institute of Statistics, which you can also find federated in datos.gob.es on trips, overnight stays, average duration and expenditure per trip. Thanks to this dataset, you can get an idea of how people travel and take it as a reference to plan your trip.

Enjoy the Water: Open Datasets for Water Activities

Access to information about beaches and bathing areas is essential for a safe and pleasant summer. The Bizkaia beach dataset provides detailed information on the characteristics of each beach, including available services, accessibility and water conditions. Similarly, this dataset of bathing areas in the Community of Madrid provides data on safe and controlled aquatic spaces in the region.

If you want a more general view, this application developed by the Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge (MITECO) with open data offers a national visualization of beaches at the national level. More recently, RTVE's data team has developed this Great Map of Spain's beaches that includes more than 3,500 destinations with specific information.

For lovers of water sports and sailing, tide prediction datasets for both Galicia and the Basque Country offer crucial information for planning activities at sea. This data allows boaters, surfers and fishermen to optimize their activities according to ocean conditions.

Smart mobility: datasets for hassle-free travel

It is not news that mobility during these months is even greater than in the rest of the year. Datasets on traffic conditions in Barcelona and the roads in Navarra provide real-time information that helps travellers avoid congestion and plan efficient routes. This information is especially valuable during periods of increased summer mobility, when roads experience a significant increase in traffic.

The applications that provide information on the price of fuel at the different Spanish petrol stations are among the most consulted on our portal throughout the year, but in summer their popularity skyrockets even more. They are interesting because they allow you to locate the service stations with the most competitive prices, optimizing the travel budget. This information can also be found in regularly updated datasets and is especially useful for long trips and route planning.

The future of open data in tourism

The convergence of open data, mobile technology and artificial intelligence is creating new opportunities to personalize and enhance the tourism experience. The datasets and resources available in datos.gob.es not only provide current information, but also serve as a basis for the development of innovative solutions that can anticipate needs, optimize resources, and create more satisfying experiences for travelers.

From route planning to selecting accommodations or finding cultural activities, these datasets and apps empower citizens and are a useful resource to maximize the enjoyment of this time of year. This summer, before you pack your bags, it's worth exploring the possibilities offered by open data.

Spain is taking a key step towards the data economy with the launch of the Data Spaces Kit, an aid programme that will subsidise the integration of public and private entities in sectoral data spaces.

Data spaces are secure ecosystems in which organizations, both public and private, share information in an interoperable way, under common rules and with privacy guarantees. These allow new products to be developed, decision-making to be improved and operational efficiency to be increased, in sectors such as health, mobility or agri-food, among others.

Today, the Ministry for Digital Transformation and Public Function, through the Secretary of State for Digitalisation and Artificial Intelligence, has published in the Official State Gazette the rules governing the granting of aid to entities interested in effectively joining a data space.

This programme, which is called the "Data Spaces Kit", will be managed by Red.es and will subsidise the costs incurred by the beneficiary entities to achieve their incorporation into an eligible data space, i.e. one that meets the requirements set out in the bases, from the day of their publication.

Recipients and Funding

This aid plan is aimed at both public and private entities, as well as Public Administrations. Among the beneficiaries of these grants are the participants, which are those entities that seek to integrate into these ecosystems to share and take advantage of data and services.

For the execution of this plan, the Government has launched aid of up to 60 million euros that will be distributed, depending on the type of entity or the level of integration as follows:

- Private and public entities with economic activity will have an aid of up to €15,000 under the effective incorporation regime or up to €30,000 if they join as a supplier.

- On the other hand, Public Administrations will have funding of up to €25,000 if they are effectively incorporated, or up to €50,000 if they do so as a supplier.

The incorporation of companies from different sectors in the data spaces will generate benefits both at the business level and for the national economy, such as increasing the innovation capacity of the beneficiary companies, the creation of new products and services based on data analysis and the improvement of operational efficiency and decision-making.

The call is expected to be published during the fourth quarter of 2025. The subsidies will be applied for on a non-competitive basis, on a first-come, first-served basis and until the available funds are exhausted.

The publication of these regulatory bases in the Official State Gazette (BOE) aims to boost the data ecosystem in Spain, strengthen the competitiveness of the economy at the global level and consolidate the financial sustainability of innovative business models.

More information:

Regulatory bases in the BOE.

Data Space Reference Center LinkedIn page.

Imagine a machine that can tell if you're happy, worried, or about to make a decision, even before you know clearly. Although it sounds like science fiction, that future is already starting to take shape. Thanks to advances in neuroscience and technology, today we can record, analyze, and even predict certain patterns of brain activity. The data that is generated from these records is known as neurodata.

In this article we will explain this concept, as well as potential use cases, based on the report "TechDispatch on Neurodata", of the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD).

What is neurodata and how is it collected?

The term neurodata refers to data that is collected directly from the brain and nervous system, using technologies such as electroencephalography (EEG), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), neural implants, or even brain-computer interfaces. In this sense, its uptake is driven by neurotechnologies.

According to the OECD, neurotechnologies are identified with "devices and procedures that are used to access, investigate, evaluate, manipulate, and emulate the structure and function of neural systems." Neurotechnologies can be invasive (if they require brain-computer interfaces that are surgically implanted in the brain) or non-invasive, with interfaces that are placed outside the body (such as glasses or headbands).

There are also two common ways to collect data:

- Passive collection, where data is captured on a regular basis without the subject having to perform any specific activity.

- Active collection, where data is collected while users perform a specific activity. For example, thinking explicitly about something, answering questions, performing physical tasks, or receiving certain stimuli.

Potential use cases

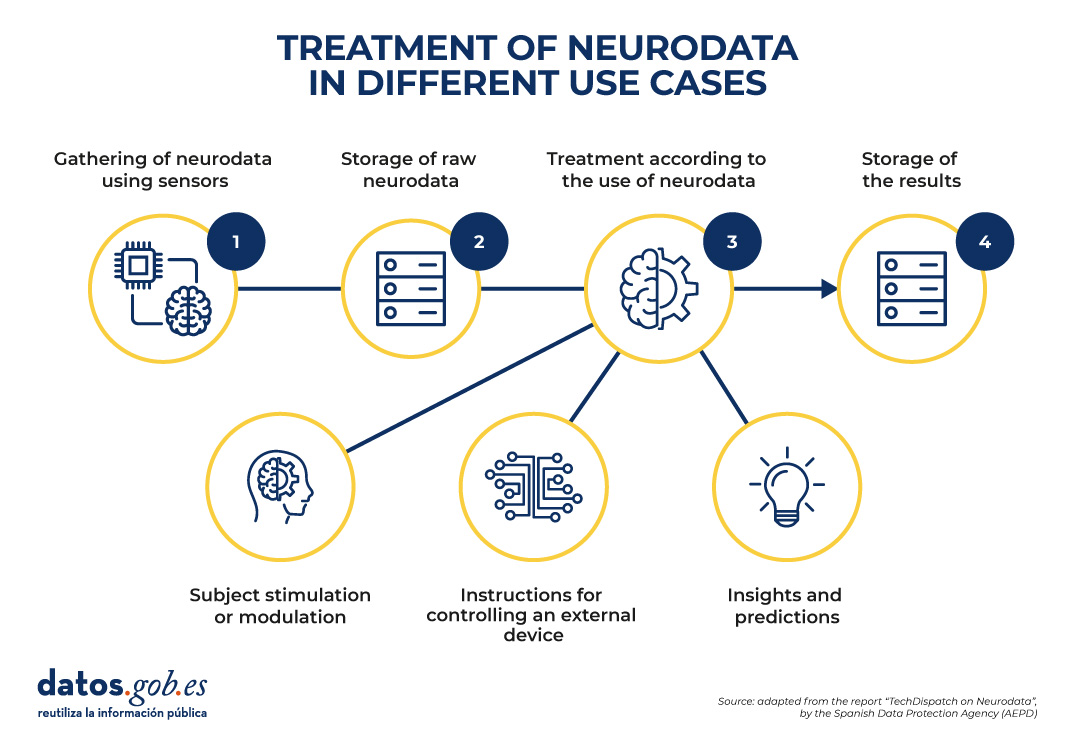

Once the raw data has been collected, it is stored and processed. The treatment will vary according to the purpose and the intended use of the neurodata.

Figure 1. Common structure to understand the processing of neurodata in different use cases. Source: "TechDispatch Report on Neurodata", by the Spanish Data Protection Agency (AEPD).

As can be seen in the image above, the Spanish Data Protection Agency has identified 3 possible purposes:

-

Neurodata processing to acquire direct knowledge and/or make predictions.

Neurodata can uncover patterns that decode brain activity in a variety of industries, including:

-

Health: Neurodata facilitates research into the functioning of the brain and nervous system, making it possible to detect signs of neurological or mental diseases, make early diagnoses, and predict their behavior. This facilitates personalized treatment from very early stages. Its impact can be remarkable, for example, in the fight against Alzheimer's, epilepsy or depression.

-

Education: through brain stimuli, students' performance and learning outcomes can be analyzed. For example, students' attention or cognitive effort can be measured. By cross-referencing this data with other internal (such as student preferences) and external (such as classroom conditions or teaching methodology) aspects, decisions can be made aimed at adapting the pace of teaching.

-

Marketing, economics and leisure: the brain's response to certain stimuli can be analysed to improve leisure products or advertising campaigns. The objective is to know the motivations and preferences that impact decision-making. They can also be used in the workplace, to track employees, learn about their skills, or determine how they perform under pressure.

- Safety and surveillance: Neurodata can be used to monitor factors that affect drivers or pilots, such as drowsiness or inattention, and thus prevent accidents.

-

Neurodata processing to control applications or devices.

As in the previous stage, it involves the collection and analysis of information for decision-making, but it also involves an additional operation: the generation of actions through mental impulses. Let's look at several examples:

-

Orthopaedic or prosthetic aids, medical implants or environment-assisted living: thanks to technologies such as brain-computer interfaces, it is possible to design prostheses that respond to the user's intention through brain activity. In addition, neurodata can be integrated with smart home systems to anticipate needs, adjust the environment to the user's emotional or cognitive states, and even issue alerts for early signs of neurological deterioration. This can lead to an improvement in patients' autonomy and quality of life.

- Robotics: The user's neural signals can be interpreted to control machinery, precision devices or applications without the need to use hands. This allows, for example, a person to operate a robotic arm or a surgical tool simply with their thinking, which is especially valuable in environments where extreme precision is required or when the operator has reduced mobility.

- Video games, virtual reality and metaverse: since neurodata allows software devices to be controlled, brain-computer interfaces can be developed that make it possible to manage characters or perform actions within a game, only with the mind, without the need for physical controls. This not only increases player immersion, but opens the door to more inclusive and personalized experiences.

- Defense: Soldiers can operate weapons systems, unmanned vehicles, drones, or explosive ordnance disposal robots remotely, increasing personal safety and operational efficiency in critical situations.

-

Neurodata treatment for the stimulation or modulation of the subject, achieving neurofeedback.

In this case, signals from the brain (outputs) are used to generate new signals that feed back into the brain (such as inputs), which involves the control of brain waves. It is the most complex field from an ethical point of view, since actions could be generated that the user is not aware of. Some examples are:

-

Psychology: Neurodata has the potential to change the way the brain responds to certain stimuli. They can therefore be used as a therapy method to treat ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), anxiety, depression, epilepsy, autism spectrum disorder, insomnia or drug addiction, among others.

- Neuroenhancement: They can also be used to improve cognitive and affective abilities in healthy people. Through the analysis and personalized stimulation of brain activity, it is possible to optimize functions such as memory, concentration, decision-making or emotional management.

Ethical challenges of the use of neurodata

As we have seen, although the potential of neurodata is enormous, it also poses great ethical and legal challenges. Unlike other types of data, neurodata can reveal deeply intimate aspects of a person, such as their desires, emotions, fears, or intentions. This opens the door to potential misuses, such as manipulation, covert surveillance, or discrimination based on neural features. In addition, they can be collected remotely and acted upon without the subject being aware of the manipulation.

This has generated a debate about the need for new rights, such as neurorights, which seek to protect mental privacy, personal identity and cognitive freedom. Various international organizations, including the European Union, are taking measures to address these challenges and advance in the creation of regulatory and ethical frameworks that protect fundamental rights in the use of neurotechnological technologies. We will soon publish an article that will delve into these aspects.

In conclusion, neurodata is a very promising advance, but not without challenges. Its ability to transform sectors such as health, education or robotics is undeniable, but so are the ethical and legal challenges posed by its use. As we move towards a future where mind and machine are increasingly connected, it is crucial to establish regulatory frameworks that ensure the protection of human rights, especially mental privacy and individual autonomy. In this way, we will be able to harness the full potential of neurodata in a fair, safe and responsible way, for the benefit of society as a whole.

Data sharing has become a critical pillar for the advancement of analytics and knowledge exchange, both in the private and public sectors. Organizations of all sizes and industries—companies, public administrations, research institutions, developer communities, and individuals—find strong value in the ability to share information securely, reliably, and efficiently.

This exchange goes beyond raw data or structured datasets. It also includes more advanced data products such as trained machine learning models, analytical dashboards, scientific experiment results, and other complex artifacts that have significant impact through reuse. In this context, the governance of these resources becomes essential. It is not enough to simply move files from one location to another; it is necessary to guarantee key aspects such as access control (who can read or modify a given resource), traceability and auditing (who accessed it, when, and for what purpose), and compliance with regulations or standards, especially in enterprise and governmental environments.

To address these requirements, Unity Catalog emerges as a next-generation metastore, designed to centralize and simplify the governance of data and data-related resources. Originally part of the services offered by the Databricks platform, the project has now transitioned into the open source community, becoming a reference standard. This means that it can now be freely used, modified, and extended, enabling collaborative development. As a result, more organizations are expected to adopt its cataloging and sharing model, promoting data reuse and the creation of analytical workflows and technological innovation.

Figure 1. Image. Source: https://docs.unitycatalog.io/

Access the data lab repository on Github.

Run the data preprocessing code on Google Colab

Objectives

In this exercise, we will learn how to configure Unity Catalog, a tool that helps us organize and share data securely in the cloud. Although we will use some code, each step will be explained clearly so that even those with limited programming experience can follow along through a hands-on lab.

We will work with a realistic scenario in which we manage public transportation data from different cities. We’ll create data catalogs, configure a database, and learn how to interact with the information using tools like Docker, Apache Spark, and MLflow.

Difficulty level: Intermediate.

Figure 2: Unity catalogue schematic

Required Resources

In this section, we’ll explain the prerequisites and resources needed to complete this lab. The lab is designed to be run on a standard personal computer (Windows, macOS, or Linux).

We will be using the following tools and environments:

- Docker Desktop: Docker allows us to run applications in isolated environments called containers. A container is like a "box" that includes everything needed for the application to run properly, regardless of the operating system.

- Visual Studio Code: Our main working environment will be a Python Notebook, which we will run and edit using the widely adopted code editor Visual Studio Code (VS Code).

- Unity Catalog: Unity Catalog is a data governance tool that allows us to organize and control access to resources such as tables, data volumes, functions, and machine learning models. In this lab, we will use its open source version, which can be deployed locally, to learn how to manage data catalogs with permission control, traceability, and hierarchical structure. Unity Catalog acts as a centralized metastore, making data collaboration and reuse more secure and efficient.

- Amazon Web Services (AWS): AWS will serve as our cloud provider to host some of the lab’s data—specifically, raw data files (such as JSON) that we will manage using data volumes. We’ll use the Amazon S3 service to store these files and configure the necessary credentials and permissions so that Unity Catalog can interact with them in a controlled manner

Key Learnings from the Lab

Throughout this hands-on exercise, participants will deploy the application, understand its architecture, and progressively build a data catalog while applying best practices in organization, access control, and data traceability.

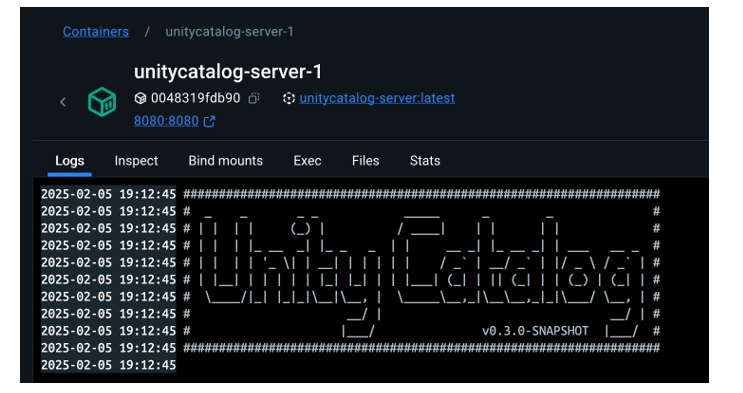

Deployment and First Steps

-

We clone the Unity Catalog repository and launch it using Docker.

-

We explore its architecture: a backend accessible via API and CLI, and an intuitive graphical user interface.

- We navigate the core resources managed by Unity Catalog: catalogs, schemas, tables, volumes, functions, and models.

Figure 2. Screenshot

What Will We Learn Here?

How to launch theapplication, understand its core components, and start interacting with it through different interfaces: the web UI, API, and CLI.

Resource Organization

-

We configure an external MySQL database as the metadata repository.

-

We create catalogs to represent different cities and schemas for various public services.

Figure 3. Screenshot

What Will We Learn Here?

How to structure data governance at different levels (city, service, dataset) and manage metadata in a centralized and persistent way.

Data Construction and Real-World Usage

-

We create structured tables to represent routes, buses, and bus stops.

-

We load real data into these tables using PySpark.

-

We set up an AWS S3 bucket as raw data storage (volumes).

- We upload JSON telemetry event files and govern them from Unity Catalog.

Figure 4. Diagram

What Will We Learn Here?

How to work with different types of data (structured and unstructured), and how to integrate them with external sources like AWS S3.

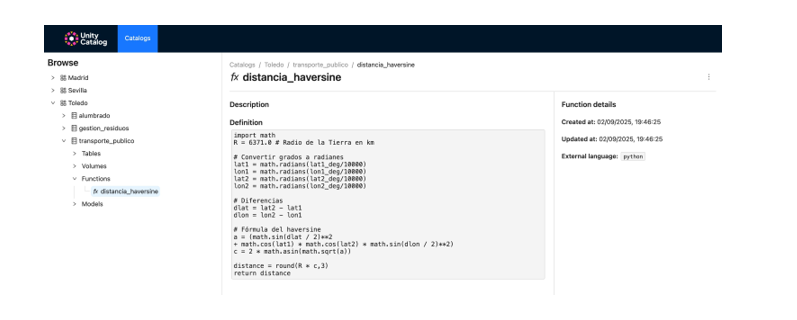

Reusable Functions and AI Models

-

We register custom functions (e.g., distance calculation) directly in the catalog.

-

We create and register machine learning models using MLflow.

- We run predictions from Unity Catalog just like any other governed resource.

Figure 5. Screenshot

What Will We Learn Here?

How to extend data governance to functions and models, and how to enable their reuse and traceability in collaborative environments.

Results and Conclusions

As a result of this hands-on lab, we gained practical experience with Unity Catalog as an open platform for the governance of data and data-related resources, including machine learning models. We explored its capabilities, deployment model, and usage through a realistic use case and a tool ecosystem similar to what you might find in an actual organization.

Through this exercise, we configured and used Unity Catalog to organize public transportation data. Specifically, you will be able to:

- Learn how to install tools like Docker and Spark.

- Create catalogs, schemas, and tables in Unity Catalog.

- Load data and store it in an Amazon S3 bucket.

- Implement a machine learning model using MLflow.

In the coming years, we will see whether tools like Unity Catalog achieve the level of standardization needed to transform how data resources are managed and shared across industries.

We encourage you to keep exploring data science! Access the full repository here

Content prepared by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies linked to the data economy. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Cities account for more than two-thirds of Europe's population and consume around 80% of energy. In this context, climate change is having a particularly severe impact on urban environments, not only because of their density, but also because of their construction characteristics, their energy metabolism and the scarcity of vegetation in many consolidated areas. One of the most visible and worrying effects is the phenomenon known as urban heat island (UHI).

Heat islands occur when the temperature in urban areas is significantly higher than in nearby rural or peri-urban areas, especially at night. This thermal differential can easily exceed five degrees Celsius under certain conditions. The consequences of this phenomenon go beyond thermal discomfort: it directly affects health, air quality, energy consumption, urban biodiversity and social equity.

In recent years, the availability of open data—especially geospatial data—has made it possible to characterize, map, and analyze urban heat islands with unprecedented accuracy. This article explores how this data can be used to design urban solutions adapted to climate change, with heat island mitigation as its focus.

What are urban heat islands and why do they occur?

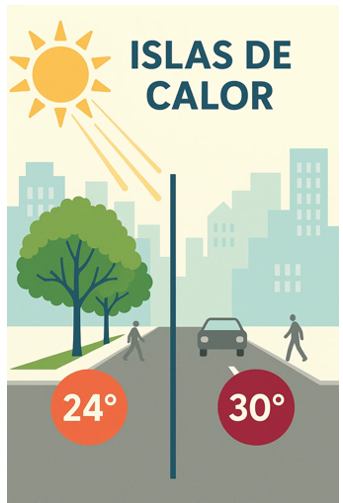

Figure 1. Illustrative element on heat islands.

To intervene effectively in heat islands, it is necessary to know where, when and how they occur. Unlike other natural hazards, the heat island effect is not visible to the naked eye, and its intensity varies depending on the time of day, time of year, and specific weather conditions. It therefore requires a solid and dynamic knowledge base, which can only be built through the integration of diverse, up-to-date and territorialized data.

At this point, open geospatial data is a critical tool. Through satellite images, urban maps, meteorological data, cadastral cartography and other publicly accessible sets, it is possible to build urban thermal models, identify critical areas, estimate differential exposures and evaluate the impact of the measures adopted.

The main categories of data that allow us to address the phenomenon of heat islands from a territorial and interdisciplinary perspective are detailed below.

Types of geoespatial data applicable to the study of the phenomenon

1. Earth observation satellite data

Thermal sensors on satellites such as Landsat 8/9 (NASA/USGS) or Sentinel-3 (Copernicus) make it possible to generate urban surface temperature maps with resolutions ranging from 30 to 1,000 metres. Although these images have spatial and temporal limitations, they are sufficient to detect patterns and trends, especially if combined with time series.

This data, accessible through platforms such as the Copernicus Open Access Hub or the USGS EarthExplorer, is essential for comparative studies between cities or for observing the temporal evolution of the same area.

2. Urban weather data

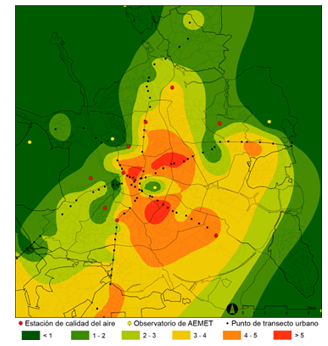

The network of AEMET stations, together with other automatic stations managed by autonomous communities or city councils, allows the evolution of air temperatures in different urban points to be analysed. In some cases, there are also citizen sensors or networks of sensors distributed in the urban space that allow real-time heat maps to be generated with high resolution.

3. Urban mapping and digital terrain models

Digital surface models (DSM), digital terrain models (DTM) and mappings derived from LIDAR allow the study of urban morphology, building density, street orientation, terrain slope and other factors that affect natural ventilation and heat accumulation. In Spain, this data is accessible through the National Center for Geographic Information (CNIG).

4. Land cover and land use databases

Databases such as Corine Land Cover of the Copernicus Programme, or land use maps at the regional level make it possible to distinguish between urbanised areas, green areas, impermeable surfaces and bodies of water. This information is key to calculating the degree of artificialization of an area and its relationship with the heat balance.

5. Inventories of urban trees and green spaces

Some municipalities publish on their open data portals the detailed inventory of urban trees, parks and gardens. These georeferenced data make it possible to analyse the effect of vegetation on thermal comfort, as well as to plan new plantations or green corridors.

6. Socioeconomic and vulnerability data

Data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE), together with the social information systems of autonomous communities and city councils, make it possible to identify the most vulnerable neighbourhoods from a social and economic point of view. Its cross-referencing with thermal data allows a climate justice dimension to be incorporated into decision-making.

Practical applications: how open data is used to act

Once the relevant data has been gathered and integrated, multiple analysis strategies can be applied to support public policies and urban projects with sustainability and equity criteria. Some of the main applications are described below.

· Heat zone mapping and vulnerability maps: Using thermal imagery, weather data, and urban layers together, heat island intensity maps can be generated at the neighborhood or block level. If these maps are combined with social, demographic and public health indicators, it is possible to build thermal vulnerability maps, which prioritize intervention in areas where high temperatures and high levels of social risk intersect. These maps allow, for example:

· Identify priority neighborhoods for urban greening.

· Plan evacuation routes or shaded areas during heat waves.

· Determine the optimal location of climate refuges.

· Assessing the impact of nature-based solutions: Open data also makes it possible to monitor the effects of certain urban actions. For example, using time series of satellite images or temperature sensors, it is possible to assess how the creation of a park or the planting of trees on a street has modified the surface temperature. This ex-post evaluation approach allows justifying public investments, adjusting designs and scaling effective solutions to other areas with similar conditions.

· Urban modelling and climate simulations: three-dimensional urban models, built from open LIDAR data or cadastral mapping, make it possible to simulate the thermal behaviour of a neighbourhood or city under different climatic and urban scenarios. These simulations, combined with tools such as ENVI-met or Urban Weather Generator, are essential to support decision-making in urban planning.

Existing studies and analysis on urban heat islands: what has been done and what we can learn

During the last decade, multiple studies have been carried out in Spain and Europe that show how open data, especially geospatial data, allow the phenomenon of urban heat islands to be characterised and analysed. These works are fundamental not only because of their specific results, but also because they illustrate replicable and scalable methodologies. Some of the most relevant are described below.

Polytechnic University of Madrid study on surface temperature in Madrid

A team from the Department of Topographic Engineering and Cartography of the UPM analysed the evolution of surface temperature in the municipality of Madrid using thermal images from the Landsat 8 satellite in the summer period. The study focused on detecting spatial changes in warmer areas and relating them to land use, urban vegetation and building density.

Figure 2. Illustrative image. Source: generated with AI

Methodology:

Remote sensing techniques were applied to extract the surface temperature from the TIRS thermal channel of the Landsat. Subsequently, a statistical analysis of correlation between thermal values and variables such as NDVI (vegetation index), type of land cover (CORINE data) and urban morphology was carried out.

Main results:

Areas with higher building density, such as the central and southern neighborhoods, showed higher surface temperatures. The presence of urban parks reduced the temperature of their immediate surroundings by 3 to 5 °C. It was confirmed that the heat island effect intensifies at night, especially during persistent heat waves.

This type of analysis is especially useful for designing urban greening strategies and for justifying interventions in vulnerable neighbourhoods.

Barcelona Climate Vulnerability Atlas

Barcelona City Council, in collaboration with experts in public health and urban geography, developed a Climate Vulnerability Atlas which includes detailed maps of heat exposure, population sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. The objective was to guide municipal policies against climate change, especially in the field of health and social services.

Figure 3. Image containing fence, exterior, buildings and grass. Source: generated with AI

Methodology:

The atlas was developed by combining open and administrative data at the census tract level. Three dimensions were analysed: exposure (air temperature and surface data), sensitivity (advanced age, density, morbidity) and adaptive capacity (access to green areas, quality of housing, facilities). The indicators were normalized and combined through multi-criteria spatial analysis to generate a climate vulnerability index. The result made it possible to locate the neighbourhoods most at risk from extreme heat and to guide municipal measures.

Main results:

Based on the atlas, the network of "climate shelters" was designed, which includes libraries, civic centers, schools and conditioned parks, activated during episodes of extreme heat. The selection of these spaces was based directly on the atlas data.

Multitemporal analysis of the heat island effect in Seville

Researchers from the University of Seville used satellite data from Sentinel-3 and Landsat 8 to study the evolution of the heat island phenomenon in the city between 2015 and 2022. The aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of certain urban actions – such as the "Green your neighbourhood" plan – and to anticipate the effects of climate change on the city.

Methodology:

Thermal imaging and NDVI data were used to calculate temperature differences between urban areas and surrounding rural areas. Supervised classification techniques were also applied to identify land uses and their evolution. Open data from tree inventories and urban shade maps were used to interpret the results.

Main results:

Specific renaturation actions have a very positive local impact, but their effect on the city as a whole is limited if they are not integrated into a metropolitan-scale strategy. The study concluded that a continuous network of vegetation and bodies of water is more effective than isolated actions.

European comparison of the Urban Heat Island Atlas (Copernicus) project

Although it is not a Spanish study, the viewer developed by Copernicus for the European Urban Atlas programme offers a comparative analysis between European cities.

Methodology:

The viewer integrates Sentinel-3 thermal imagery, land cover data, and urban mapping to assess the severity of the heat island effect.

Figure 4. Illustration: Infographic showing the main factors causing the urban heat island effect (UHI). Urban areas retain heat due to tall buildings, impermeable surfaces and heat-retaining materials, while green areas are cooler Source: Urban heat islands.

Main results:

This type of tool allows smaller cities to have a first approximation of the phenomenon without the need to develop their own models. As it is based on open and free data, the viewer allows direct consultations by technicians and citizens.

Current limitations and challenges

Despite progress in opening up data, there are still significant challenges:

-

Territorial inequality: not all cities have the same quality and quantity of data.

-

Irregular update: Some sets are released on a one-off basis and are not updated regularly.

-

Low granularity: Data is often aggregated by districts or census tracts, making street-scale interventions difficult.

-

Lack of technical capacities: Many local governments do not have staff specialized in geospatial analysis.

- Little connection with citizens: the knowledge generated from data does not always translate into visible or understandable actions for the population.

Conclusion: building climate resilience from geoespatial data

Urban heat islands are not a new phenomenon, but in the context of climate change they take on a critical dimension. Cities that do not plan based on data will be increasingly exposed to episodes of extreme heat, with unequal impacts among their populations.

Open data—and in particular geospatial data—offers a strategic opportunity to transform this threat into a lever for change. With them we can identify, anticipate, intervene and evaluate. But for this to happen, it is essential to:

· Consolidate accessible, up-to-date and quality data infrastructures.

· To promote collaboration between levels of government, research centres and citizens.

· Train municipal technicians in the use of geospatial tools.

· Promote a culture of evidence-based decision-making and climate sensitivity.

Data does not replace politics, but it allows it to be founded, improved and made more equitable. In a global warming scenario, having open geospatial data is a key tool to make our cities more livable and better prepared for the future.

Content prepared by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Sport has always been characterized by generating a lot of data, statistics, graphs... But accumulating figures is not enough. It is necessary to analyze the data, draw conclusions and make decisions based on it. The advantages of sharing data in this sector go beyond mere sports, having a positive impact on health and the economic sphere. they go beyond mere sports, having a positive impact on health and the economic sphere.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has also reached the professional sports sector and its ability to process huge amounts of data has opened the door to making the most of the potential of all that information. Manchester City, one of the best-known football clubs in the British Premier League, was one of the pioneers in using artificial intelligence to improve its sporting performance: it uses AI algorithms for the selection of new talent and has collaborated in the development of WaitTime, an artificial intelligence platform that manages the attendance of crowds in large sports and leisure venues. In Spain, Real Madrid, for example, incorporated the use of artificial intelligence a few years ago and promotes forums on the impact of AI on sport.

Artificial intelligence systems analyze extensive volumes of data collected during training and competitions, and are able to provide detailed evaluations on the effectiveness of strategies and optimization opportunities. In addition, it is possible to develop alerts on injury risks, allowing prevention measures to be established, or to create personalized training plans that are automatically adapted to each athlete according to their individual needs. These tools have completely changed contemporary high-level sports preparation. In this post we are going to review some of these use cases.

From simple observation to complete data management to optimize results

Traditional methods of sports evaluation have evolved into highly specialized technological systems. Artificial intelligence and machine learning tools process massive volumes of information during training and competitions, converting statistics, biometric data and audiovisual content into strategic insights for the management of athletes' preparation and health.

Real-time performance analysis systems are one of the most established implementations in the sports sector. To collect this data, it is common to see athletes training with bands or vests that monitor different parameters in real time. Both these and other devices and sensors record movements, speeds and biometric data. Heart rate, speed or acceleration are some of the most common data. AI algorithms process this information, generating immediate results that help optimize personalized training programs for each athlete and tactical adaptations, identifying patterns to locate areas for improvement.

In this sense, sports artificial intelligence platforms evaluate both individual performance and collective dynamics in the case of team sports. To evaluate the tactical area, different types of data are analyzed according to the sports modality. In endurance disciplines, speed, distance, rhythm or power are examined, while in team sports data on the position of the players or the accuracy of passes or shots are especially relevant.

Another advance is AI cameras, which allow you to follow the trajectory of players on the field and the movements of different elements, such as the ball in ball sports. These systems generate a multitude of data on positions, movements and patterns of play. The analysis of these historical data sets allows us to identify strategic strengths and vulnerabilities both our own and those of our opponents. This helps to generate different tactical options and improve decision-making before a competition.

Health and well-being of athletes

Sports injury prevention systems analyze historical data and metrics in real-time. Its algorithms identify injury risk patterns, allowing personalized preventive measures to be taken for each athlete. In the case of football, teams such as Manchester United, Liverpool, Valencia CF and Getafe CF have been implementing these technologies for several years.

In addition to the data we have seen above, sports monitoring platforms also record physiological variables continuously: heart rate, sleep patterns, muscle fatigue and movement biomechanics. Wearable devices with artificial intelligence capabilities detect indicators of fatigue, imbalances, or physical stress that precede injuries. With this data, the algorithms predict patterns that detect risks and make it easier to act preventively, adjusting training or developing specific recovery programs before an injury occurs. In this way, training loads, rep volume, intensity and recovery periods can be calibrated according to individual profiles. This predictive maintenance for athletes is especially relevant for teams and clubs in which athletes are not only sporting assets, but also economic ones. In addition, these systems also optimise sports rehabilitation processes, reducing recovery times in muscle injuries by up to 30% and providing predictions on the risk of relapse.

While not foolproof, the data indicates that these platforms predict approximately 50% of injuries during sports seasons, although they cannot predict when they will occur. The application of AI to healthcare in sport thus contributes to the extension of professional sports careers, facilitating optimal performance and the athlete's athletic well-being in the long term.

Improving the audience experience

Artificial intelligence is also revolutionizing the way fans enjoy sport, both in stadiums and at home. Thanks to natural language processing (NLP) systems, viewers can follow comments and subtitles in real time, facilitating access for people with hearing impairments or speakers of other languages. Manchester City has recently incorporated this technology for the generation of real-time subtitles on the screens of its stadium. These applications have also reached other sports disciplines: IBM Watson has developed a functionality that allows Wimbledon fans to watch the videos with highlighted commentary and AI-generated subtitles.

In addition, AI optimises the management of large capacities through sensors and predictive algorithms, speeding up access, improving security and customising services such as seat locations. Even in broadcasts, AI-powered tools offer instant statistics, automated highlights, and smart cameras that follow the action without human intervention, making the experience more immersive and dynamic. The NBA uses Second Spectrum, a system that combines cameras with AI to analyze player movements and create visualizations, such as passing routes or shot probabilities. Other sports, such as golf or Formula 1, also use similar tools that enhance the fan experience.

Data privacy and other challenges

The application of AI in sport also poses significant ethical challenges. The collection and analysis of biometric information raises doubts about the security and protection of athletes' personal data, so it is necessary to establish protocols that guarantee the management of consent, as well as the ownership of such data.

Equity is another concern, as the application of artificial intelligence gives competitive advantages to teams and organizations with greater economic resources, which can contribute to perpetuating inequalities.

Despite these challenges, artificial intelligence has radically transformed the professional sports landscape. The future of sport seems to be linked to the evolution of this technology. Its application promises to continue to elevate athlete performance and the public experience, although some challenges need to be overcome.

Imagine you want to know how many terraces there are in your neighbourhood, how the pollen levels in the air you breathe every day are evolving or whether recycling in your city is working well. All this information exists in your municipality's databases, but it sits in spreadsheets and technical documents that only experts know how to interpret.

This is where open data visualisation initiativescome in: they transform those seemingly cold numbers into stories that anyone can understand at a glance. A colourful graph showing the evolution of traffic on your street, an interactive map showing the green areas of your city, or an infographic explaining how the municipal budget is spent. These tools make public information accessible, useful and, moreover, comprehensible to all citizens.

Moreover, the advantages of this type of solution are not only for the citizens, but also benefit the Administration that carries out the exercise, because it allows:

- Detect and correct data errors.

- Add new sets to the portal.

- Reduce the number of questions from citizens.

- Generate more trust on the part of society.

Therefore, visualising open data brings government closer to citizens, facilitates informed decision-making, helps public administrations to improve their open data offer and creates a more participatory society where we can all better understand how the public sector works. In this post, we present some examples of open data visualisation initiatives in regional and municipal open data portals.

Visualiza Madrid: bringing data closer to the public

Madrid City Council's open data portal has developed the initiative "Visualiza Madrid", a project born with the specific objective of making open data and its potential reach the general public , transcending specialised technical profiles. As Ascensión Hidalgo Bellota, Deputy Director General for Transparency of Madrid City Council, explained during the IV National Meeting on Open Data, "this initiative responds to the need to democratise access to public information".

Visualiza Madrid currently has 29 visualisations that cover different topics of interest to citizens, from information on hotel and restaurant terraces to waste management and urban traffic analysis. This thematic diversity demonstrates the versatility of visualisations as a tool for communicating information from very diverse sectors of public administration.

In addition, the initiative has received external recognition this year through the Audaz 2,025 Awards, an initiative of the Spanish chapter of the Open Government Academic Network (RAGA Spain).The initiative has also received external recognition through the Audaz 2,025 Awards.

Castilla y León: comprehensive analysis of regional data

The Junta de Castilla y León has also developed a portal specialised in analysis and visualisations that stands out for its comprehensive approach to the presentation of regional data. Its visualisation platform offers a systematic approach to the analysis of regional information, allowing users to explore different dimensions of the reality of Castilla y Leónthrough interactive and dynamic tools.

This initiative allows complex information to be presented in a structured and understandable way, facilitating both academic analysis and citizen use of the data. The platform integrates different sources of regional information, creating a coherent ecosystem of visualisations that provides a panoramic view of different aspects of regional management. Among the topics it offers are data on tourism, the labour market and budget execution. All the visualisations are made with open data sets from the regional portal of Castilla y León .

The Castilla y León approach demonstrates how visualisations can serve as a tool for territorial analysis, providing valuable insights on economic, social and demographic dynamics that are fundamental for the planning and evaluation of regional public policies.

Canary Islands: technological integration with interactive widgets .

On the other hand, the Government of the Canary Islands has opted for an innovative strategy through the implementation of widgets that allow the integration of open data visualisations of the Instituto Canario de Estadística (ISTAC) in different platforms and contexts. This technological approach represents a qualitative leap in the distribution and reuse of public data visualisations.

The widgets developed by the Canary Islands make it easier for third parties to embed official visualisations in their own applications, websites or analyses, exponentially expanding the scope and usefulness of Canary Islands open data. This strategy not only multiplies the points of access to public information, but also fosters the creation of a collaborative ecosystem where different actors can benefit from and contribute to the value of open data.

The Canarian initiative illustrates how technology can be used to create scalable and flexible solutions that maximise the impact of investments in open data visualisation, establishing a replicable model for other administrations seeking to amplify the reach of their transparency initiatives.

Lessons learned and best practices

By way of example, the cases analysed reveal common patterns that can serve as a guide for future initiatives. The orientation towards the general public, beyond specialised technical users, emerges as an opportunity factor for the success of these platforms. To maintain the interest and relevance of the visualisations, it is important to offer thematic diversity and to update the data regularly.

Technological integration and interoperability, as demonstrated in the case of the Canary Islands, open up new possibilities to maximise the impact of public investments in data visualisation. Likewise, external recognition and participation in professional networks, as evidenced in the case of Madrid, contribute to continuous improvement and the exchange of best practices between administrations.

In general terms, open data visualisation initiatives represent a very valuable opportunity in the transparency and open government strategy of Spanish public administrations. The cases of Madrid, Castilla y León, as well as the Canary Islands, are examples of the enormous potential for transforming public data into tools for citizen empowerment and improved public management.

The success of these initiatives lies in their ability to connect government information with the real needs of citizens, creating bridges of understanding that strengthen the relationship between administration and society. As these experiences mature and consolidate, it will be crucial to keep the focus on the usability, accessibility and relevance of visualisations, ensuring that open data truly delivers on its promise to contribute to a more informed, participatory and democratic society.

Open data visualisation is not just a technical issue, but a strategic opportunity to redefine public communication and strengthen the foundations of a truly open and transparent administration.

In an increasingly interconnected and complex world, geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) has become an essential tool for defence and security decision-making . The ability to collect, analyse and interpret geospatial data enables armed forces and security agencies to better understand the operational environment, anticipate threats and plan operations more effectively.

In this context, satellite data, classified but also open data, have acquired significant relevance. Programmes such as Copernicus of the European Union provide free and open access to a wide range of Earth observation data, which democratises access to critical information and fosters collaboration between different actors.

This article explores the role of data in geospatial intelligence applied to defence, highlighting its importance, applications and Spain's leadership in this field.

Geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) is a discipline that combines the collection, analysis and interpretation of geospatial data to support decision making in a variety of areas, including defence, security and emergency management. This data may include satellite imagery, remotely sensed information, geographic information system (GIS) data and other sources that provide information on the location and characteristics of the terrain.

In the defence domain, GEOINT enables military analysts and planners to gain a detailed understanding of the operational environment, identify potential threats and plan operations with greater precision. It also facilitates coordination between different units and agencies, improving the effectiveness of joint operations.

Defence application

The integration of open satellite data into geospatial intelligence has significantly expanded defence capabilities. Some of the most relevant applications are presented below:

Figure 1. GEOINT applications in defence. Source: own elaboration

Geospatial intelligence not only supports the military in making tactical decisions, but also transforms the way military, surveillance and emergency response operations are planned and executed. Here we present concrete use cases where GEOINT, supported by open satellite data, has had a decisive impact.

Monitoring of military movements in conflicts

Case. Ukraine War (2,022-2,024)

Organisations such as the EU Satellite Centre (SatCen) and NGOs such as the Conflict Intelligence Team have used Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 (Copernicus) imagery for the Conflict Intelligence Team :

- Detect concentrations of Russian troops and military equipment.

- Analyse changes to airfields, bases or logistics routes.

- Support independent verification of events on the ground.

This has been key to EU and NATO decision-making, without the need to resort to classified data.

Maritime surveillance and border control

Case. FRONTEX operations in the Mediterranean

GEOINT powered by Sentinel-1 (radar) and Sentinel-3 (optical + altimeter) allows:

- Identify unauthorised vessels, even under cloud cover or at night.

- Integrate alerts with AIS (automatic ship identification system).

- Coordinate rescue and interdiction operations.

Advantage: Sentinel-1's synthetic aperture radar (SAR) can see through clouds, making it ideal for continuous surveillance.

Support to peace missions and humanitarian aid

Case. Earthquake in Syria/Turkey (2,023)

Open data (Sentinel-2, Landsat-8, PlanetScope free after catastrophe) were used for:

- Detect collapsed areas and assess damage.

- Plan safe access routes.

Coordinate camps and resources with military support.

Spain's role

Spain has demonstrated a significant commitment to the development and application of geospatial intelligence in defence.

|

European Union Satellite Centre (SatCen) |

Project Zeus of the Spanish Army |

Participation in European Programmes | National capacity building |

|

Located in Torrejón de Ardoz, SatCen is a European Union agency that provides geospatial intelligence products and services to support security and defence decision-making. Spain, as host country, plays a central role in SatCen operations. |

The Spanish Army has launched the Zeus project, a technological initiative that integrates artificial intelligence, 5G networks and satellite data to improve operational capabilities. This project aims to create a tactical combat cloud to enable greater interoperability and efficiency in military operations. |

Spain actively participates in European programmes related to Earth observation and geospatial intelligence, such as Copernicus and MUSIS. In addition, it collaborates in bilateral and multilateral initiatives for satellite capacity building and data sharing. |

At the national level, Spain has invested in the development of its own geospatial intelligence capabilities, including the training of specialised personnel and the acquisition of advanced technologies. These investments reinforce the country's strategic autonomy and its ability to contribute to international operations. |

Figure 2. Comparative table of Spain's participation in different satellite projects. Source: own elaboration

Challenges and opportunities

While open satellite data offers many advantages, it also presents certain challenges that need to be addressed to maximise its usefulness in the defence domain.

-

Data quality and resolution: While open data is valuable, it often has limitations in terms of spatial and temporal resolution compared to commercial or classified data. This may affect its applicability in certain operations requiring highly accurate information.

-

Data integration: The integration of data from multiple sources, including open, commercial and classified data, requires systems and processes to ensure interoperability and consistency of information. This involves technical and organisational challenges that must be overcome.

-

Security and confidentiality: The use of open data in defence contexts raises questions about the security and confidentiality of information. It is essential to establish security protocols and measures to protect sensitive information and prevent its misuse.

- Opportunities for collaboration: Despite these challenges, open satellite data offer significant opportunities for collaboration between different actors, including governments, international organisations, the private sector and civil society. Such collaboration can improve the effectiveness of defence operations and contribute to greater global security.

Recommendations for strengthening the use of open data in defence

Based on the above analysis, some key recommendations can be drawn to better exploit the potential of open data:

-

Strengthening open data infrastructures: consolidate national platforms integrating open satellite data for both civilian and military use, with a focus on security and interoperability.

-

Promotion of open geospatial standards (OGC, INSPIRE): Ensure that defence systems integrate international standards that allow the combined use of open and classified sources.

-

Specialised training: foster the development of capabilities in GEOINT analysis with open data, both in the military domain and in collaboration with universities and technology centres.

-

Civil-military cooperation: establish protocols to facilitate the exchange of data between civilian agencies (AEMET, IGN, Civil Protection) and defence actors in crisis or emergency situations.

- Support to R&D&I: to foster research projects exploring the advanced use of open data (e.g. AI applied to Sentinel) with dual applications (civilian and security).

Conclusion

Geospatial intelligence and the use of open satellite data have transformed the way armed forces and security agencies plan and execute their operations. In a context of multidimensional threats and constantly evolving scenarios, having accurate, accessible and up-to-date information is more than an advantage: it is a strategic necessity.

Open data has established itself as a fundamental asset not only because it is free of charge, but also because of its ability to democratise access to critical information, foster transparency and enable new forms of collaboration between military, civilian and scientific actors. In particular:

- Improve the resilience of defence systems by enabling broader, cross-cutting analysis of the operating environment.

- Increase interoperability, as open formats and standards facilitate exchange between countries and agencies.

- They drive innovationby providing startups, research centres and universities with access to quality data that would otherwise be inaccessible.

In this context, Spain has demonstrated a clear commitment to this strategic vision, both through its national institutions and its active role in European programmes such as Copernicus, Galileo and the common defence missions.

Content prepared by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.