Data is a fundamental resource for improving our quality of life because it enables better decision-making processes to create personalised products and services, both in the public and private sectors. In contexts such as health, mobility, energy or education, the use of data facilitates more efficient solutions adapted to people's real needs. However, in working with data, privacy plays a key role. In this post, we will look at how data spaces, the federated computing paradigm and federated learning, one of its most powerful applications, provide a balanced solution for harnessing the potential of data without compromising privacy. In addition, we will highlight how federated learning can also be used with open data to enhance its reuse in a collaborative, incremental and efficient way.

Privacy, a key issue in data management

As mentioned above, the intensive use of data requires increasing attention to privacy. For example, in eHealth, secondary misuse of electronic health record data could violate patients' fundamental rights. One effective way to preserve privacy is through data ecosystems that prioritise data sovereignty, such as data spaces. A dataspace is a federated data management system that allows data to be exchanged reliably between providers and consumers. In addition, the data space ensures the interoperability of data to create products and services that create value. In a data space, each provider maintains its own governance rules, retaining control over its data (i.e. sovereignty over its data), while enabling its re-use by consumers. This implies that each provider should be able to decide what data it shares, with whom and under what conditions, ensuring compliance with its interests and legal obligations.

Federated computing and data spaces

Data spaces represent an evolution in data management, related to a paradigm called federated computing, where data is reused without the need for data flow from data providers to consumers. In federated computing, providers transform their data into privacy-preserving intermediate results so that they can be sent to data consumers. In addition, this enables other Data Privacy-Enhancing Technologies(Privacy-Enhancing Technologies)to be applied. Federated computing aligns perfectly with reference architectures such as Gaia-X and its Trust Framework, which sets out the principles and requirements to ensure secure, transparent and rule-compliant data exchange between data providers and data consumers.

Federated learning

One of the most powerful applications of federated computing is federated machine learning ( federated learning), an artificial intelligence technique that allows models to be trained without centralising data. That is, instead of sending the data to a central server for processing, what is sent are the models trained locally by each participant.

These models are then combined centrally to create a global model. As an example, imagine a consortium of hospitals that wants to develop a predictive model to detect a rare disease. Every hospital holds sensitive patient data, and open sharing of this data is not feasible due to privacy concerns (including other legal or ethical issues). With federated learning, each hospital trains the model locally with its own data, and only shares the model parameters (training results) centrally. Thus, the final model leverages the diversity of data from all hospitals without compromising the individual privacy and data governance rules of each hospital.

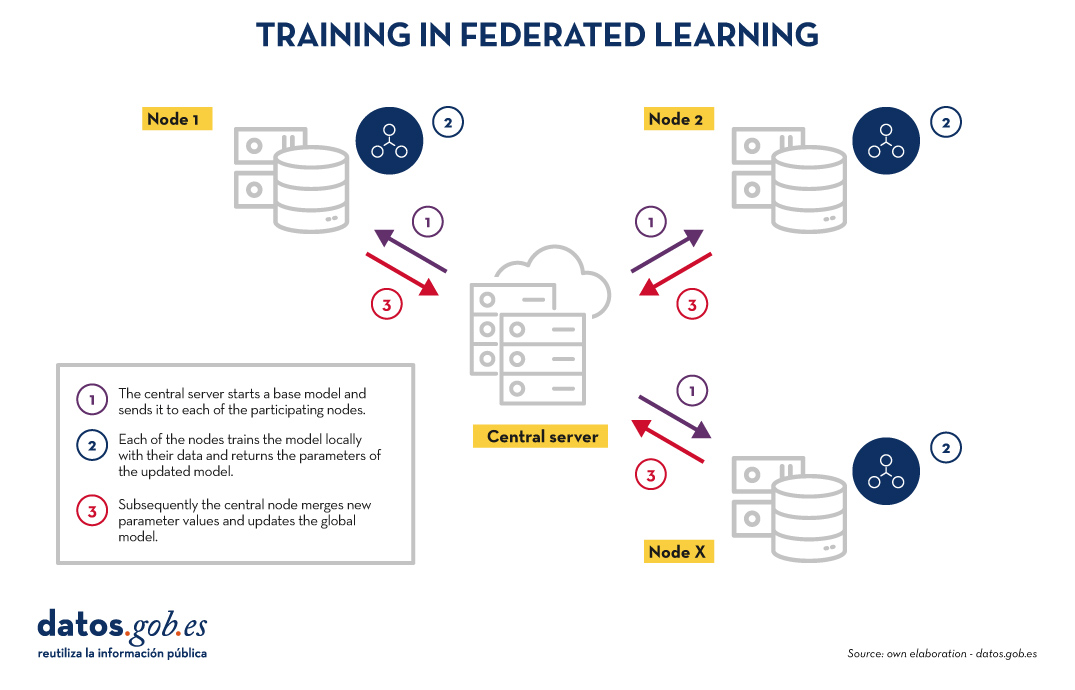

Training in federated learning usually follows an iterative cycle:

- A central server starts a base model and sends it to each of the participating distributed nodes.

- Each node trains the model locally with its data.

- Nodes return only the parameters of the updated model, not the data (i.e. data shuttling is avoided).

- The central server aggregates parameter updates, training results at each node and updates the global model.

- The cycle is repeated until a sufficiently accurate model is achieved.

Figure 1. Visual representing the federated learning training process. Own elaboration

This approach is compatible with various machine learning algorithms, including deep neural networks, regression models, classifiers, etc.

Benefits and challenges of federated learning

Federated learning offers multiple benefits by avoiding data shuffling. Below are the most notable examples:

- Privacy and compliance: by remaining at source, data exposure risks are significantly reduced and compliance with regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is facilitated.

- Data sovereignty: Each entity retains full control over its data, which avoids competitive conflicts.

- Efficiency: avoids the cost and complexity of exchanging large volumes of data, speeding up processing and development times.

- Trust: facilitates frictionless collaboration between organisations.

There are several use cases in which federated learning is necessary, for example:

- Health: Hospitals and research centres can collaborate on predictive models without sharing patient data.

- Finance: banks and insurers can build fraud detection or risk-sharing analysis models, while respecting the confidentiality of their customers.

- Smart tourism: tourist destinations can analyse visitor flows or consumption patterns without the need to unify the databases of their stakeholders (both public and private).

- Industry: Companies in the same industry can train models for predictive maintenance or operational efficiency without revealing competitive data.

While its benefits are clear in a variety of use cases, federated learning also presents technical and organisational challenges:

- Data heterogeneity: Local data may have different formats or structures, making training difficult. In addition, the layout of this data may change over time, which presents an added difficulty.

- Unbalanced data: Some nodes may have more or higher quality data than others, which may skew the overall model.

- Local computational costs: Each node needs sufficient resources to train the model locally.

- Synchronisation: the training cycle requires good coordination between nodes to avoid latency or errors.

Beyond federated learning

Although the most prominent application of federated computing is federated learning, many additional applications in data management are emerging, such as federated data analytics (federated analytics). Federated data analysis allows statistical and descriptive analyses to be performed on distributed data without the need to move the data to the consumers; instead, each provider performs the required statistical calculations locally and only shares the aggregated results with the consumer according to their requirements and permissions. The following table shows the differences between federated learning and federated data analysis.

|

Criteria |

Federated learning |

Federated data analysis |

|

Target |

Prediction and training of machine learning models. | Descriptive analysis and calculation of statistics. |

| Task type | Predictive tasks (e.g. classification or regression). | Descriptive tasks (e.g. means or correlations). |

| Example | Train models of disease diagnosis using medical images from various hospitals. | Calculation of health indicators for a health area without moving data between hospitals. |

| Expected output | Modelo global entrenado. | Resultados estadísticos agregados. |

| Nature | Iterativa. | Directa. |

| Computational complexity | Alta. | Media. |

| Privacy and sovereignty | High | Average |

| Algorithms | Machine learning. | Statistical algorithms. |

Figure 1. Comparative table. Source: own elaboration

Federated learning and open data: a symbiosis to be explored

In principle, open data resolves privacy issues prior to publication, so one would think that federated learning techniques would not be necessary. Nothing could be further from the truth. The use of federated learning techniques can bring significant advantages in the management and exploitation of open data. In fact, the first aspect to highlight is that open data portals such as datos.gob.es or data.europa.eu are federated environments. Therefore, in these portals, the application of federated learning on large datasets would allow models to be trained directly at source, avoiding transfer and processing costs. On the other hand, federated learning would facilitate the combination of open data with other sensitive data without compromising the privacy of the latter. Finally, the nature of a wide variety of open data types is very dynamic (such as traffic data), so federated learning would enable incremental training, automatically considering new updates to open datasets as they are published, without the need to restart costly training processes.

Federated learning, the basis for privacy-friendly AI

Federated machine learning represents a necessary evolution in the way we develop artificial intelligence services, especially in contexts where data is sensitive or distributed across multiple providers. Its natural alignment with the concept of the data space makes it a key technology to drive innovation based on data sharing, taking into account privacy and maintaining data sovereignty.

As regulation (such as the European Health Data Space Regulation) and data space infrastructures evolve, federated learning, and other types of federated computing, will play an increasingly important role in data sharing, maximising the value of data, but without compromising privacy. Finally, it is worth noting that, far from being unnecessary, federated learning can become a strategic ally to improve the efficiency, governance and impact of open data ecosystems.

Jose Norberto Mazón, Professor of Computer Languages and Systems at the University of Alicante. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

In the current landscape of data analysis and artificial intelligence, the automatic generation of comprehensive and coherent reports represents a significant challenge. While traditional tools allow for data visualization or generating isolated statistics, there is a need for systems that can investigate a topic in depth, gather information from diverse sources, and synthesize findings into a structured and coherent report.

In this practical exercise, we will explore the development of a report generation agent based on LangGraph and artificial intelligence. Unlike traditional approaches based on templates or predefined statistical analysis, our solution leverages the latest advances in language models to:

- Create virtual teams of analysts specialized in different aspects of a topic.

- Conduct simulated interviews to gather detailed information.

- Synthesize the findings into a coherent and well-structured report.

Access the data laboratory repository on Github.

Run the data preprocessing code on Google Colab.

As shown in Figure 1, the complete agent flow follows a logical sequence that goes from the initial generation of questions to the final drafting of the report.

Figure 1. Agent flow diagram.

Application Architecture

The core of the application is based on a modular design implemented as an interconnected state graph, where each module represents a specific functionality in the report generation process. This structure allows for a flexible workflow, recursive when necessary, and with capacity for human intervention at strategic points.

Main Components

The system consists of three fundamental modules that work together:

1. Virtual Analysts Generator

This component creates a diverse team of virtual analysts specialized in different aspects of the topic to be investigated. The flow includes:

- Initial creation of profiles based on the research topic.

- Human feedback point that allows reviewing and refining the generated profiles.

- Optional regeneration of analysts incorporating suggestions.

This approach ensures that the final report includes diverse and complementary perspectives, enriching the analysis.

2. Interview System

Once the analysts are generated, each one participates in a simulated interview process that includes:

- Generation of relevant questions based on the analyst's profile.

- Information search in sources via Tavily Search and Wikipedia.

- Generation of informative responses combining the obtained information.

- Automatic decision on whether to continue or end the interview based on the information gathered.

- Storage of the transcript for subsequent processing.

The interview system represents the heart of the agent, where the information that will nourish the final report is obtained. As shown in Figure 2, this process can be monitored in real time through LangSmith, an open observability tool that allows tracking each step of the flow.

Figure 2. System monitoring via LangGraph. Concrete example of an analyst-interviewer interaction.

3. Report Generator

Finally, the system processes the interviews to create a coherent report through:

- Writing individual sections based on each interview.

- Creating an introduction that presents the topic and structure of the report.

- Organizing the main content that integrates all sections.

- Generating a conclusion that synthesizes the main findings.

- Consolidating all sources used.

The Figure 3 shows an example of the report resulting from the complete process, demonstrating the quality and structure of the final document generated automatically.

Figure 3. View of the report resulting from the automatic generation process to the prompt "Open data in Spain".

What can you learn?

This practical exercise allows you to learn:

Integration of advanced AI in information processing systems:

- How to communicate effectively with language models.

- Techniques to structure prompts that generate coherent and useful responses.

- Strategies to simulate virtual teams of experts.

Development with LangGraph:

- Creation of state graphs to model complex flows.

- Implementation of conditional decision points.

- Design of systems with human intervention at strategic points.

Parallel processing with LLMs:

- Parallelization techniques for tasks with language models.

- Coordination of multiple independent subprocesses.

- Methods for consolidating scattered information.

Good design practices:

- Modular structuring of complex systems.

- Error handling and retries.

- Tracking and debugging workflows through LangSmith.

Conclusions and future

This exercise demonstrates the extraordinary potential of artificial intelligence as a bridge between data and end users. Through the practical case developed, we can observe how the combination of advanced language models with flexible architectures based on graphs opens new possibilities for automatic report generation.

The ability to simulate virtual expert teams, perform parallel research and synthesize findings into coherent documents, represents a significant step towards the democratization of analysis of complex information.

For those interested in expanding the capabilities of the system, there are multiple promising directions for its evolution:

- Incorporation of automatic data verification mechanisms to ensure accuracy.

- Implementation of multimodal capabilities that allow incorporating images and visualizations.

- Integration with more sources of information and knowledge bases.

- Development of more intuitive user interfaces for human intervention.

- Expansion to specialized domains such as medicine, law or sciences.

In summary, this exercise not only demonstrates the feasibility of automating the generation of complex reports through artificial intelligence, but also points to a promising path towards a future where deep analysis of any topic is within everyone's reach, regardless of their level of technical experience. The combination of advanced language models, graph architectures and parallelization techniques opens a range of possibilities to transform the way we generate and consume information.

The evolution of generative AI has been dizzying: from the first great language models that impressed us with their ability to reproduce human reading and writing, through the advanced RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) techniques that quantitatively improved the quality of the responses provided and the emergence of intelligent agents, to an innovation that redefines our relationship with technology: Computer use.

At the end of April 2020, just one month after the start of an unprecedented period of worldwide home confinement due to the SAR-Covid19 global pandemic, we spread from datos.gob.es the large GPT-2 and GPT-3 language models. OpenAI, founded in 2015, had presented almost a year earlier (February 2019) a new language model that was able to generate written text virtually indistinguishable from that created by a human. GPT-2 had been trained on a corpus (set of texts prepared to train language models) of about 40 GB (Gigabytes) in size (about 8 million web pages), while the latest family of models based on GPT-4 is estimated to have been trained on TB (Terabyte) sized corpora; a thousand times more.

In this context, it is important to talk about two concepts:

- LLLMs (Large Language Models ): are large-scale language models, trained on vast amounts of data and capable of performing a wide range of linguistic tasks. Today, we have countless tools based on these LLMs that, by field of expertise, are able to generate programming code, ultra-realistic images and videos, and solve complex mathematical problems. All major companies and organisations in the digital-technology sector have embarked on integrating these tools into their different software and hardware products, developing use cases that solve or optimise specific tasks and activities that previously required a high degree of human intervention.

- Agents: The user experience with artificial intelligence models is becoming more and more complete, so that we can ask our interface not only to answer our questions, but also to perform complex tasks that require integration with other IT tools. For example, we not only ask a chatbot for information on the best restaurants in the area, but we also ask them to search for table availability for specific dates and make a reservation for us. This extended user experience is what artificial intelligence agentsprovide us with. Based on the large language models, these agents are able to interact with the outside world (to the model) and "talk" to other services via APIs and programming interfaces prepared for this purpose.

Computer use

However, the ability of agents to perform actions autonomously depends on two key elements: on the one hand, their concrete programming - the functionality that has been programmed or configured for them; on the other hand, the need for all other programmes to be ready to "talk" to these agents. That is, their programming interfaces must be ready to receive instructions from these agents. For example, the restaurant reservation application has to be prepared, not only to receive forms filled in by a human, but also requests made by an agent that has been previously invoked by a human using natural language. This fact imposes a limitation on the set of activities and/or tasks that we can automate from a conversational interface. In other words, the conversational interface can provide us with almost infinite answers to the questions we ask it, but it is severely limited in its ability to interact with the outside world due to the lack of preparation of the rest of computer applications.

This is where Computer use comes in. With the arrival of the Claude 3.5 Sonnet model, Anthropic has introduced Computer use, a beta capability that allows AI to interact directly with graphical user interfaces.

How does Computer use work?

Claude can move your computer cursor as if it were you, click buttons and type text, emulating the way humans operate a computer. The best way to understand how Computer use works in practice is to see it in action. Here is a link directly to the YouTube channel of the specific Computer use section.

Figure 1. Screenshot from Anthropic's YouTube channel, Computer use specific section.

Would you like to try it?

If you've made it this far, you can't miss out without trying it with your own hands.

Here is a simple guide to testing Computer use in an isolated environment. It is important to take into account the security recommendations that Antrophic proposes in its Computer use guidelines. This feature of the Claude Sonet model can perform actions on a computer and this can be potentially dangerous, so it is recommended to carefully review the security warning of Computer use.

All official developer documentation can be found in the antrophic's official Github repository. In this post, we have chosen to run Computer use in a Docker container environment. It is the easiest and safest way to test it. If you don't already have it, you can follow the simple official guidelines to pre-install it on your system.

To reproduce this test we propose to follow this script step by step:.

- Anthropic API Key. To interact with Claude Sonet you need an Anthropic account which you can create for free here. Once inside, you can go to the API Keys section and create a new one for your test

- Once you have your API Key, you must run this command in your terminal, substituting your key where it says "%your_api_key%":

3. If everything went well, you will see these messages in your terminal and now you just have to open your browser and type this url in the navigation bar: htttp://localhost:8080/.

You will see your interface open:

Figure 2. Computer use interface.

You can now go to explore how Computer use works. We suggest the following prompt to get you started:

We suggest you start small. For example, ask them to open a browser and search for something. You can also ask him to give you information about your computer or operating system. Gradually, you can ask for more complex tasks. We have tested this prompt and after several trials we have managed to get Computer use to perform the complete task.

Open a browser, navigate to the datos.gob.es catalogue, use the search engine to locate a dataset on: Public security. Traffic accidents. 2014; Locate the file in csv format; download and open it with free Office.

Potential uses in data platforms such as datos.gob.es

In view of this first experimental version of Computer use, it seems that the potential of the tool is very high. We can imagine how many more things we can do thanks to this tool. Here are some ideas:

- We could ask the system to perform a complete search of datasets related to a specific topic and summarise the main results in a document. In this way, if for example we write an article on traffic data in Spain, we could unattended obtain a list of the main open datasets of traffic data in Spain in the datos.gob.es catalogue.

- In the same way, we could request a summary in the same way, but in this case, not of dataset, but of platform items.

- A slightly more sophisticated example would be to ask Claude, through the conversational interface of Computer use, to make a series of calls to the data API.gob.es to obtain information from certain datasets programmatically. To do this, we open a browser and log into an application such as Postman (remember at this point that Computer use is in experimental mode and does not allow us to enter sensitive data such as user credentials on web pages). We can then ask you to search for information about the datos.gob.es API and execute an http call, taking advantage of the fact that this API does not require authentication.

Through these simple examples, we hope that we have introduced you to a new application of generative AI and that you have understood the paradigm shift that this new capability represents. If the machine is able to emulate the use of a computer as we humans do, unimaginable new opportunities will open up in the coming months.

Content prepared by Alejandro Alija, expert in Digital Transformation and Innovation. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The enormous acceleration of innovation in artificial intelligence (AI) in recent years has largely revolved around the development of so-called "foundational models". Also known as Large [X] Models (Large [X] Models or LxM), Foundation Models, as defined by the Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM) of the Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence's (HAI) Stanford University's models that have been trained on large and highly diverse datasets and can be adapted to perform a wide range of tasks using techniques such as fine-tuning (fine-tuning).

It is precisely this versatility and adaptability that has made foundational models the cornerstone of the numerous applications of artificial intelligence being developed, since a single base architecture can be used across a multitude of use cases with limited additional effort.

Types of foundational models

The "X" in LxM can be replaced by several options depending on the type of data or tasks for which the model is specialised. The best known by the public are the LLM (Large Language Models), which are at the basis of applications such as ChatGPT or Gemini, and which focus on natural language understanding and generation.. LVMs (Large Vision Models), such as DINOv2 or CLIP, are designed tointerpret images and videos, recognise objects or generate visual descriptions.. There are also models such as Operator or Rabbit R1 that fall into the LAM (Large Action Models) category and are aimed atexecuting actions from complex instructions..

As regulations have emerged in different parts of the world, so have other definitions that seek to establish criteria and responsibilities for these models to foster confidence and security. The most relevant definition for our context is that set out in the European Union AI Regulation (AI Act), which calls them "general-purpose AI models" and distinguishes them by their "ability to competently perform a wide variety of discrete tasks" and because they are "typically trained using large volumes of data and through a variety of methods, such as self-supervised, unsupervised or reinforcement learning".

Foundational models in Spanish and other co-official languages

Historically, English has been the dominant language in the development of large AI models, to the extent that around 90% of the training tokens of today's large models are drawn from English texts. It is therefore logical that the most popular models, for example OpenAI's GPT family, Google's Gemini or Meta's Llama, are more competent at responding in English and perform less well when used in other languages such as Spanish.

Therefore, the creation of foundational models in Spanish, such as ALIA, is not simply a technical or research exercise, but a strategic move to ensure that artificial intelligence does not further deepen the linguistic and cultural asymmetries that already exist in digital technologies in general. The development of ALIA, driven by the Spain's Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2024, "based on the broad scope of our languages, spoken by 600 million people, aims to facilitate the development of advanced services and products in language technologies, offering an infrastructure marked by maximum transparency and openness".

Such initiatives are not unique to Spain. Other similar projects include BLOOM, a 176-billion-parameter multilingual model developed by more than 1,000 researchers worldwide and supporting 46 natural languages and 13 programming languages. In China, Baidu has developed ERNIE, a model with strong Mandarin capabilities, while in France the PAGNOL model has focused on improving French capabilities. These parallel efforts show a global trend towards the "linguistic democratisation" of AI.

Since the beginning of 2025, the first language models in the four co-official languages, within the ALIA project, have been available. The ALIA family of models includes ALIA-40B, a model with 40.40 billion parameters, which is currently the most advanced public multilingual foundational model in Europeand which was trained for more than 8 months on the MareNostrum 5 supercomputer, processing 6.9 trillion tokens equivalent to about 33 terabytes of text (about 17 million books!). Here all kinds of official documents and scientific repositories in Spanish are included, from congressional journals to scientific repositories or official bulletins to ensure the richness and quality of your knowledge.

Although this is a multilingual model, Spanish and co-official languages have a much higher weight than usual in these models, around 20%, as the training of the model was designed specifically for these languages, reducing the relevance of English and adapting the tokens to the needs of Spanish, Catalan, Basque and Galician.. As a result, ALIA "understands" our local expressions and cultural nuances better than a generic model trained mostly in English.

Applications of the foundational models in Spanish and co-official languages

It is still too early to judge the impact on specific sectors and applications that ALIA and other models that may be developed from this experience may have. However, they are expected to serve as a basis for improving many Artificial Intelligence applications and solutions:.

- Public administration and government: ALIA could give life to virtual assistants that attend to citizens 24 hours a day for procedures such as paying taxes, renewing ID cards, applying for grants, etc., as it is specifically trained in Spanish regulations. In fact, a pilot for the Tax Agency using ALIA, which would aim to streamline internal procedures, has already been announced.

- Education: A model such as ALIA could also be the basis for personalised virtual tutors to guide students in Spanish and co-official languages. For example, assistants who explain concepts of mathematics or history in simple language and answer questions from the students, adapting to their level since, knowing our language well, they would be able to provide important nuances in the answers and understand the typical doubts of native speakers in these languages. They could also help teachers by generating exercises or summaries of readings or assisting them in correcting students' work.

- Health: ALIA could be used to analyse medical texts and assist healthcare professionals with clinical reports, medical records, information leaflets, etc. For example, it could review patient files to extract key elements, or assist professionals in the diagnostic process. In fact, the Ministry of Health is planning a pilot application with ALIA to improve early detection of heart failure in primary care.

- Justice: In the legal field, ALIA would understand technical terms and contexts of Spanish law much better than a non-specialised model as it has been trained with legal vocabulary from official documents. An ALIA-based virtual paralegal could be able to answer basic citizen queries, such as how to initiate a given legal procedure, citing the applicable law. The administration of justice could also benefit from much more accurate machine translations of court documents between co-official languages.

Future lines

The development of foundation models in Spanish, as in other languages, is beginning to be seen outside the United States as a strategic issue that contributes to guaranteeing the technological sovereignty of countries. Of course, it will be necessary to continue training more advanced versions (models with up to 175 billion parameters are targeted, which would be comparable to the most powerful in the world), incorporating new open data, and fine-tuning applications. From the Data Directorate and the SEDIA it is intended to continue to support the growth of this family of models, to keep it at the forefront and ensure its adoption.

On the other hand, these first foundational models in Spanish and co-official languages have initially focused on written language, so the next natural frontier could be multimodality. Integrating the capacity to manage images, audio or video in Spanish together with the text would multiply its practical applications, since the interpretation of images in Spanish is one of the areas where the greatest deficiencies are detected in the large generic models.

Ethical issues will also need to be monitored to ensure that these models do not perpetuate bias and are useful for all groups, including those who speak different languages or have different levels of education. In this respect, Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is not optional, but a fundamental requirement to ensure its responsible adoption.. The National AI Supervisory Agency, the research community and civil society itself will have an important role to play here.

Content prepared by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalization. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

The General direction of traffic (DGT in its Spanish acronym) is the body responsible for ensuring safety and fluidity on the roads in Spain. Among other activities, it is responsible for the issuing of permits, traffic control and the management of infringements.

As a result of its activity, a large amount of data is generated, much of which is made available to the public as open data. These datasets not only promote transparency but are also a tool to encourage innovation and improve road safety through their re-use by researchers, companies, public administrations and interested citizens.

In this article we will review some of these datasets, including application examples.

How to access the DGT's datasets

DGT datasets provide detailed and structured information on various aspects of road safety and mobility in Spain, ranging from accident statistics to vehicle and driver information. The temporal continuity of these datasets, available from the beginning of the century to the present day, enables longitudinal analyses that reflect the evolution of mobility and road safety patterns in Spain.

Users can access datasets in different spaces:

- DGT en cifras. It is a section of the General direction of traffic that offers a centralised access to statistics and key data related to road safety, vehicles and drivers in Spain. This portal includes detailed information on accidents, complaints, vehicle fleet and technical characteristics of vehicles, among other topics. It also provides historical and comparative analyses to assess trends and design strategies to improve road safety.

- National Access Point (NAP). Managed by the DGT, it is a platform designed to centralise and facilitate access to road and traffic data, including updates. This portal has been created under the framework of the European Directive 2010/40/EU and brings together information provided by various traffic management bodies, road authorities and infrastructure operators. Available data includes traffic incidents, electric vehicle charging points, low-emission zones and car park occupancy, among others. It aims to promote interoperability and the development of intelligent solutions that improve road safety and transport efficiency.

While the NAP is focused on real-time data and technological solutions, DGT en cifras focuses on providing statistics and historical information for analysis and decision making. In addition, the NAP collects data not only from the DGT, but also from other agencies and private companies.

Most of these data are available through datos.gob.es.

Examples of DGT datasets

Some examples of datasets that can be found in datos.gob.es are:

- Accidents with casualties: includes detailed information on fatalities, hospitalised and minor injuries, as well as circumstances by road type. This data helps to understand why accidents happen and who is involved, to identify risky situations and to detect dangerous behaviour on the road. It is useful for creating better prevention campaigns, detecting black spots on the roads and helping authorities to make more informed decisions. They are also of interest to public health professionals, urban planners and insurance companies working to reduce accidents and their consequences.

- Census of drivers: provides a complete x-ray of who has a driving licence in Spain. The information is particularly useful for understanding the evolution of the driver fleet, identifying demographic trends and analysing the penetration of different types of licences by territory and gender.

- Car registrations by make and engine capacity: shows which new cars Spaniards bought, organised by brand and engine power. The information allows consumer trends to be identified. This data is valuable for manufacturers, dealers and automotive analysts, who can study the market performance in a given year. They are also useful for researchers in mobility, environment and economics, allowing to analyse the evolution of the Spanish vehicle fleet and its impact in terms of emissions, energy consumption and market trends.

Use cases of DGT datasets

The publication of this data in an open format enables innovation in areas such as accident prevention, the development of safer road infrastructure, the development of evidence-based public policies, and the creation of mobility-related technology applications. Some examples are given below:

DGT's own use of data

The DGT itself reuses its data to create tools that facilitate the visualisation of the information and bring it closer to citizens in a simple way. This is the case of the Traffic status and incident map, which is constantly and automatically updated with the information entered 24 hours a day by the Civil Guard Traffic Group and the heads of the Traffic Management Centres of the DGT, the Generalitat de Catalunya and the Basque Government. Includes information on roads affected by weather phenomena (e.g. ice, floods, etc.) and forecast developments.

In addition, the DGT also uses its data to carry out studies that provide information on certain aspects related to mobility and road safety, which are very useful for decision-making and policy-making. One example is this study which analyses the behaviour and activity of certain groups in traffic accidents in order to propose proactive measures. Another example: this project to implement a computer system that identifies, through geolocation, the critical points with the highest accident rates on roads for their treatment and transfer of conclusions.

Use of data by third parties

The datasets provided by the DGT are also reused by other public administrations, researchers, entrepreneurs and private companies, fostering innovation in this field. Thanks to them, we find apps that allow users to access detailed information about vehicles in Spain (such as technical characteristics and inspection history and other data) or that provide information about the most dangerous places for cyclists.

In addition, its combination with advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence allows extracting even more value from the data, facilitating the identification of patterns and helping citizens and authorities to take preventive measures. One example is the Waze application, which has implemented an artificial intelligence-based functionality to identify and alert drivers to high-crashstretches of road, known as "black spots". This system combines historical accident data with analysis of road characteristics, such as gradients, traffic density and intersections, to provide accurate and highly useful alerts. The application notifies users in advance when they are approaching these dangerous areas, with the aim of reducing risks and improving road safety. This innovation complements the data provided by the DGT, helping to save lives by encouraging more cautious driving.

For those who would like to get a taste and practice with DGT data, from datos.gob.es we have a step-by-step data science exercise. Users will be able to analyse these datasets and use predictive models to estimate the evolution of the electric vehicle in Spain. Documented code development and free-to-use tools are used for this purpose. All the material generated is available for reuse in the GitHub repository of datos.gob.es.

In short, the DGT's data sets offer great opportunities for reuse, even more so when combined with disruptive technologies. This is driving innovation, sustainability and safer, more connected transport, which is helping to transform urban and rural mobility.

Once again this year, the European Commission organised the EU Open Data Day, one of the world's leading open data and innovation events. On 19-20 March, the European Convention Centre in Luxembourg brings together experts, government officials and academics to share knowledge, experience and progress on open data in Europe.

During these two intense days, which also could be followed online explored crucial topics such as governance, quality, interoperability and the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on open data. This event has become an essential forum for fostering the development of policies and practices that promote transparency and data-driven innovation across the European Union. In this post, we review each of the presentations at the event.

Openness and data history

To begin with, the Director General of the European Union Publications Office, Hilde Hardeman, opened the event by welcoming the attendees and setting the tone for the discussions to follow. Helena Korjonen and Emma Schymanski, two experts from the University of Luxembourg, then presented a retrospective entitled "A data journey: from darkness to enlightenment", exploring the evolution of data storage and sharing over 18,000 years. From cave paintings to modern servers, this historical journey highlighted how many of today's open data challenges, such as ownership, preservation and accessibility, have deep roots in human history.

This was followed by a presentation by Slava Jankin, Professor at the Centre for AI in Government at the University of Birmingham, on AI-driven digital twins and open data to create dynamic simulations of governance systems, which allow policymakers to test reforms and predict outcomes before implementing them.

Use cases between open data and AI

On the other hand, several use cases were also presented, such as Lithuania's practical experience in the comprehensive cataloguing of public data. Milda Aksamitauskas of the University of Wisconsin, addressed the governance challenges and communication strategies employed in the project and presented lessons on how other countries could adapt similar methods to improve transparency and data-driven decision-making.

In relation, scientific coordinator Bastiaan van Loenen presented the findings of the project he is working on, ODECO of Horizon 2020, focusing on the creation of sustainable open data ecosystems. As van Loenen explained, the research, which has been conducted over four years by 15 researchers, has explored user needs and governance structures for seven different groups, highlighting how circular, inclusive and skills-based approaches can provide economic and social value to open data ecosystems.

In addition, artificial intelligence was at the forefront throughout the event. Assistant Professor Anastasija Nikiforova from the University of Tartu offered a revealing insight into how artificial intelligence can transform government open data ecosystems. In his presentation, "Data for AI or AI for data" he explored eight different roles that AI can play. For example, AI can serve as a open data portal 'cleanser' and even retrieve data from the ecosystem, providing valuable insights for policymakers and researchers on how to effectively leverage AI in open data initiatives.

Also using AI-powered tools, we find the EU Open Research Repository launched by Zenodo in 2024, an open science initiative that provides a tailored research repository for EU research funding recipients. Lars Holm Nielsen's presentation dhighlighted how AI-driven tools and high-quality open datasets reduce the cost and effort of data cleaning, while ensuring adherence to the FAIR principles.

The day continued with a speech by Maroš Šefčovič, European Commissioner for Trade and Economic Security, Inter-institutional Relations and Transparency, who underlined the European Commission's commitment to open data as a key pillar for transparency and innovation in the European Union.

Interoperability and data quality

After a break, Georges Lobo and Pavlina Fragkou, programme and project coordinator of SEMIC respectively, explained how the Semantic Interoperability Centre Europe (SEMIC) improves interoperable data exchange in Europe through theData Catalogue Vocabulary Application Profile (DCAT-AP) and Linked Data Event Streams (LDES). His presentation highlighted how these standards facilitate the efficient publication and consumption of data, with case studies such as the Rijksmuseum and the European Union Railway Agency demonstrating their value in fostering interoperable and sustainable data ecosystems.

Barbara Šlibar from the University of Zagreb then provided a detailed analysis of metadata quality in European open datasets, revealing significant disparities in five key dimensions. His study, based on random samples from data.europa.eu, underlined the importance of improving metadata practices and raising awareness among stakeholders to improve the usability and value of open data in Europe.

Then, Bianca Sammer, from Bavarian Agency for Digital Affairs shared her experience creating Germany's open data portal in just one year. His presentation "Unlocking the Potential" highlighted innovative solutions to overcome challenges in open data management. For example, they achieved an automated improvement of metadata quality, a reusable open source infrastructure and participation strategies for public administrations and users.

Open data today and on the horizon

The second day started with interventions by Rafał Rosiński, Undersecretary of State at the Ministry of Digital Affairs of Poland, who presented the Polish Presidency's perspective on open data and digital transformation, and Roberto Viola, Director General of the European Commission's Directorate-General for Communication Networks, Content and Technology, who spoke about the European path to digital innovation.

After the presentation of the day, the presentations on use cases and innovative proposals in open databegan. First, Stefaan Verhulst, co-founder of the New York governance lab GovLab, dubbed the historic moment we are living through as the "fourth wave of open data" characterised by the integration of generative artificial intelligence with open data to address social challenges.. His presentation raised crucial questions about how AI-based conversational interfaces can improve accessibility, what it means for open data to be "AI-ready" and how to build sustainable data-driven solutions that balance openness and trust.

Christos Ellinides, Director General for Translation at the European Commission, then highlighted the importance of language data for AI on the continent. With 25 years of data spanning multiple languages and the expertise to develop multilingual services based on artificial intelligence, the Commission is at the forefront in the field of linguistic data spaces and in the use of European high-performance computing infrastructures to exploit data and AI.

Open data re-use use cases

Reuse brings multiple benefits. Kjersti Steien, from the Norwegian digitisation agency, presented Norway's national data portal, data.norge.no, which employs an AI-powered search engine to improve data discoverability. Using Google Vertex, the engine allows users to find relevant datasets without needing to know the exact terms used by data providers, demonstrating how AI can improve data reuse and adapt to emerging language models.

Beyond Norway, use cases from other cities and countries were also discussed. Sam Hawkins, Ember's UK Data Programme Manager, underlined the importance of open energy data in advancing the clean energy transition and ensuring system flexibility.

Another case was presented by Marika Eik from the University of Estonia, which leverages urban data and cross-sector collaboration to improve sustainability and community impact. His session examined a city-level approach to sustainability metrics and CO2 footprint calculations, drawing on data from municipalities, real estate operators, research institutions and mobility analysts to provide replicable models for improving environmental responsibility.

Raphaël Kergueno of Transparency International EU explained how Integrity Watch EU leverages open data to improve transparency and accountability in the Union. This initiative re-uses datasets such as the EU Transparency Register and the European Commission's meeting records to increase public awareness of lobbying activities and improve legislative oversight, demonstrating the potential of open data to strengthen democratic governance.

Also, Kate Larkin of the European Marine Observatory, presented the European Marine Observation and Data Network, highlighting how pan-European marine data services, which adhere to the FAIR principles contribute to initiatives such as the European Green Pact, maritime spatial planning and the blue economy. His presentation showed practical use cases demonstrating the integration of marine data into wider data ecosystems such as the European Digital Twin Ocean.

Data visualisation and communication

In addition to use cases, the EU Open Data Days 2025 highlighted data visualisation as a mechanism to bring open data to the people. In this vein, Antonio Moneo, CEO of Tangible Data, explored how transforming complex datasets into physical sculptures fosters data literacy and community engagement.

On the other hand, Jan Willem Tulp, founder of TULP interactive, examined how visual design influences the perception of data. His session explored how design elements such as colour, scale and focus can shape narratives and potentially introduce bias, highlighting the responsibilities of data visualisers to maintain transparency while crafting compelling visual narratives.

Education and data literacy

Davide Taibi, researcher at the Italian National Research Council, shared experiences on the integration of data literacy and AI in educational pathways, based on EU-funded projects such as DATALIT, DEDALUS and SMERALD. These initiatives piloted digitally enhanced learning modules in higher education, secondary schools and vocational training in several EU Member States, focusing on competence-oriented approaches and IT-based learning systems.

Nadieh Bremer, founder of Visual Cinnamon, explored how creative approaches to data visualisation can reveal the intricate bonds between people, cultures and concepts. Examples included a family tree of 3,000 European royals, relationships in UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage and cross-cultural constellations in the night sky, demonstrating how iterative design processes can uncover hidden patterns in complex networks.

Digital artist Andreas Refsgaard closed the presentations with a reflection on the intersection of generative AI, art and data science. Through artistic and engaging examples, he invited the audience to reflect on the vast potential and ethical dilemmas arising from the growing influence of digital technologies in our daily lives.

In summary, the EU Open Data Day 2025 has once again demonstrated the importance of these meetings in driving the evolution of the open data ecosystem in Europe. The discussions, presentations and case studies shared during these two days have highlighted not only the progress made, but also the remaining challenges and emerging opportunities. In a context where artificial intelligence, sustainability and citizen participation are transforming the way we use and value data, events like this one are essential to foster collaboration, share knowledge and develop strategies that maximise the social and economic value of open data. The continued engagement of European institutions, national governments, academia and civil society will be essential to build a more robust, accessible and impactful open data ecosystem that responds to the challenges of the 21st century and contributes to the well-being of all European citizens.

You can return to the recordings of each lecture here.

Geospatial data has driven improvements in a number of sectors, and energy is no exception. This data allows us to better understand our environment in order to promote sustainability, innovation and informed decision-making.

One of the main providers of open geospatial data is Copernicus, the European Union's Earth observation programme. Through a network of satellites called Sentinel and data from ground, sea and airborne sources, Copernicus provides geospatial information freely accessible through various platforms.

Although Copernicus data is useful in many areas, such as fighting climate change, urban planning or agriculture, in this article we will focus on its role in driving sustainability and energy efficiency. The availability of high quality open data fosters innovation in this sector by promoting the development of new tools and applications that improve energy management and use. Here are some examples.

Climate prediction to improve production

Geospatial data provide detailed information on weather conditions, air quality and other factors, which are essential for understanding and predicting environmental phenomena, such as storms or droughts, that affect energy production and distribution.

One example is this project which provides high-resolution wind forecasts to serve the oil and gas, aviation, shipping and defence sectors. It uses data from satellite observations and numerical models, including information on ocean currents, waves and sea surface temperature from the "Copernicus Marine Service". Thanks to its granularity, it can provide an accurate weather forecasting system at a very local scale, allowing a higher level of accuracy in the behaviour of extreme weather and climate phenomena.

Optimisation of resources

The data provided by Copernicus also allows the identification of the best locations for the installation of energy generation centres, such as solar and wind farms, by facilitating the analysis of factors such as solar radiation and wind speed. In addition, they help monitor the efficiency of these facilities, ensuring that they are operating at maximum capacity.

In this regard, a project has been developed to find the best site for a combined floating wind and wave energy system (i.e. based on wave motion). By obtaining both energies with a single platform, this solution saves space and reduces the impact on the ground, while improving efficiency. Wind and waves arrive at different times at the platform, so capturing both elements helps reduce variability and smoothes overall electricity production. Thanks to the Copernicus data (obtained from the Atlantic Service - Biscay Iberia Ireland - Ocean Wave Reanalysis), the provider of this situation was able to obtain separate components of wind and wave waves, which allowed a more complete understanding of the directionality of both elements. This work led to the selection of Biscay Marine Energy Platform (BiMEP). for the deployment of the device.

Another example is Mon Toit Solaire, an integrated web-based decision support system for the development of rooftop photovoltaic power generation. This tool simulates and calculates the energy potential of a PV project and provides users with reliable technical and financial information. It uses solar radiation data produced by the "Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service", together with three-dimensional urban topographic data and simulations of tax incentives, energy costs and prices, allowing the return on investment to be calculated.

Environmental monitoring and impact assessment.

Geospatial information allows for improved environmental monitoring and accurate impact assessments in the energy sector. This data allows energy companies to identify environmental risks associated with their operations, design strategies to mitigate their impact and optimise their processes towards greater sustainability. In addition, they support environmental compliance by providing objective data-driven reporting, encouraging more responsible and environmentally friendly energy development.

Among the challenges posed by the conservation of ocean biodiversity, man-made underwater noise is recognised as a serious threat and is regulated at European level. In order to assess the impact on marine life of wind farms along the southern coast of France, this project uses high-resolution statistical sound maps, which provide a detailed view of coastal processes, with an hourly time frequency and a high spatial resolution of up to 1.8 km. In particular, they use information from the "Mediterranean Sea Physics Analysis and Forecasting" and "World Ocean Hourly Sea Surface Wind and Stress" services.

Emergency and environmental disaster management.

In disaster situations or extreme weather events, geospatial data can help quickly assess damage and coordinate emergency responses more efficiently.

They can also predict how spills will behave. This is the aim of the Marine Research Institute of the University of Klaipeda, which has developed a system for monitoring and forecasting chemical and microbiological pollution episodes using a high-resolution 3D operational hydrodynamic model. They use the Copernicus "Physical Analysis and Forecasts of the Baltic Sea". The model provides real-time, five-day forecasts of water currents, addressing the challenges posed by shallow waters and port areas. It aims to help manage pollution incidents, particularly in pollution-prone regions such as ports and oil terminals.

These examples highlight the usefulness of geospatial data, especially those provided by programmes such as Copernicus. The fact that companies and institutions can freely access this data is revolutionising the energy sector, contributing to a more efficient, sustainable and resilient system.

Housing is one of the main concerns of Spanish citizens, according to the January 2025 barometer of the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS). In order to know the real situation of access to housing, it is necessary to have public, updated and quality data, which allows all the actors in this ecosystem to carry out analyses and make informed decisions.

In this article we will review some examples of available open data, as well as tools and solutions that have been created based on them to bring this information closer to citizens.

Examples of housing data Open data can have several uses in this sector:

- Enable public bodies to understand citizens' needs and develop policies accordingly.

- Helping individuals to find homes to rent or buy.

- Providing information to builders and companies so that they can develop housing that responds to these needs.

Therefore, in this field, the most used data include those referring to housing, but also to demographic and social aspects, often with a high geospatial component. Some of the most popular datasets in this sense are the Housing and Consumer Price Indexes of the National Statistics Institute (INE) or the Cadastre data.

Different public bodies have made available to the public spaces where they gather various data related to housing. This is the case of Barcelona City Council and its portal "Housing in data", an environment that centralises access to information and data from various sources, including datasets from its open data portal.

Another example is the Madrid City Council data visualisation portal, which includes dashboards with information on the number of residential properties by district or neighbourhood, as well as their cadastral value, with direct access to download the data used.

Further examples of bodies that also provide access to this type of information are the Junta de Castilla y León, the Basque Government or the Comunidad Valenciana. In addition, those who wish to do so can find a multitude of data related to housing in the National Catalogue of Open Data, hosted here, at datos.gob.es.

It should also be noted that it is not only public bodies that open data related to this subject. A few months ago, the real estate portalidealistareleased a dataset with detailed information on thousands of properties in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia. It is available as a package in R via Github.

Tools and solutions to bring this data closer to citizens

Data such as the above can be reused for multiple purposes, as we showed in previous articles and as we can see in this new approach to the various use cases:

Data journalism

The media use open housing data to provide a more accurate picture of the housing market situation, helping citizens understand the dynamics affecting prices, supply and demand. By accessing data on price developments, housing availability or related public policies, the media can generate reports and infographics that explain in an accessible way the situation and how these factors impact on people's daily lives. These articles provide citizens with relevant information, in a simple way, to make decisions about their housing situation.

One example is this article which allows us to visualise, neighbourhood by neighbourhood, the price of rent and access to housing according to income, for which open data from the Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda, the Cadastre and the INE, among others, were used. Along the same lines is this article on the percentage of income to be spent on rent.

Reporting and policy development

Open data on housing is used by public bodies such as the Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda in its Housing and Land Observatory, where electronic statistical bulletins are generated that integrate data available from the main official statistical sources. The aim is to monitor the sector from different perspectives and throughout the different phases of the process (land market, built products, accessibility and financing, etc.). The Ministry of Housing and Urban Agenda also uses data from various sources, such as the Tax Agency, the Cadastre or the INE, for its State Reference System of Housing Rental Prices, which defines ranges of rental price values for housing in areas declared as stressed.

Offer of real estate services

Open data can be valuable for the construction sector: open information on land use and permits is consulted before excavation work is undertaken and new construction starts.

In addition, some of the companies using open data are real estate websites. These portals reuse open data sets to provide users with comparable property prices, neighbourhood crime statistics or proximity to public educational, health and recreational facilities. This is helped, for example, by tools such as Location intelligence, which provides access to census data, rental prices, housing characteristics or urban planning. Public bodies can also help in this field with their own solutions, such as Donde Vivo, from the Government of Aragon, which allows you to obtain an interactive map and related information of the nearest points of interest, educational and health centres as well as geostatistical information of the place where you live.

There are also tools that help to forecast future costs, such as Urban3r, where users can visualise different indicators that help them to know the energy demand data of residential buildings in their current state and after undergoing energy refurbishment, as well as the estimated costs of these interventions.This is a field where data-driven disruptive technologies, such as artificial intelligence, will play an increasingly important role, optimising processes and facilitating decision-making for both home buyers and suppliers. By analysing large volumes of data, AI can predict market trends, identify areas of high demand or provide personalised recommendations based on the needs of each user. Some companies have already launched chatbots, which answer users' questions, but AI can even help create projects for the development of affordable and sustainable housing.

In short, we are in a field where new technologies are going to make it easier and easier for citizens to find out about the supply of housing, but this supply must be aligned with the needs of users. It is therefore necessary to continue promoting the opening up of quality data, which will help to understand the situation and promote public policies and solutions that facilitate access to housing.

The concept of data commons emerges as a transformative approach to the management and sharing of data that serves collective purposes and as an alternative to the growing number of macrosilos of data for private use. By treating data as a shared resource, data commons facilitate collaboration, innovation and equitable access to data, emphasising the communal value of data above all other considerations. As we navigate the complexities of the digital age - currently marked by rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and the continuing debate about the challenges in data governance- the role that data commons can play is now probably more important than ever.

What are data commons?

The data commons refers to a cooperative framework where data is collected, governed and shared among all community participants through protocols that promote openness, equity, ethical use and sustainability. The data commons differ from traditional data-sharing models mainly in the priority given to collaboration and inclusion over unitary control.

Another common goal of the data commons is the creation of collective knowledge that can be used by anyone for the good of society. This makes them particularly useful in addressing today's major challenges, such as environmental challenges, multilingual interaction, mobility, humanitarian catastrophes, preservation of knowledge or new challenges in health and health care.

In addition, it is also increasingly common for these data sharing initiatives to incorporate all kinds of tools to facilitate data analysis and interpretation , thus democratising not only the ownership of and access to data, but also its use.

For all these reasons, data commons could be considered today as a criticalpublic digital infrastructure for harnessing data and promoting social welfare.

Principles of the data commons

The data commons are built on a number of simple principles that will be key to their proper governance:

- Openness and accessibility: data must be accessible to all authorised persons.

- Ethical governance: balance between inclusion and privacy.

- Sustainability: establish mechanisms for funding and resources to maintain data as a commons over time.

- Collaboration: encourage participants to contribute new data and ideas that enable their use for mutual benefit.

- Trust: relationships based on transparency and credibility between stakeholders.

In addition, if we also want to ensure that the data commons fulfil their role as public domain digital infrastructure, we must guarantee other additional minimum requirements such as: existence of permanent unique identifiers , documented metadata , easy access through application programming interfaces (APIs), portability of the data, data sharing agreements between peers and ability to perform operations on the data.

The important role of the data commons in the age of Artificial Intelligence

AI-driven innovation has exponentially increased the demand for high-quality, diverse data sets a relatively scarce commodityat a large scale that may lead to bottlenecks in the future development of the technology and, at the same time, makes data commons a very relevant enabler for a more equitable AI. By providing shared datasets governed by ethical principles, data commons help mitigate common risks such as risks, data monopolies and unequal access to the benefits of AI.

Moreover, the current concentration of AI developments also represents a challenge for the public interest. In this context, the data commons hold the key to enable a set of alternative, public and general interest-oriented AI systems and applications, which can contribute to rebalancing this current concentration of power. The aim of these models would be to demonstrate how more democratic, public interest-oriented and purposeful systems can be designed based on public AI governance principles and models.

However, the era of generative AI also presents new challenges for data commons such as, for example and perhaps most prominently, the potential risk of uncontrolled exploitation of shared datasets that could give rise to new ethical challenges due to data misuse and privacy violations.

On the other hand, the lack of transparency regarding the use of the data commons by the AI could also end up demotivating the communities that manage them, putting their continuity at risk. This is due to concerns that in the end their contribution may be benefiting mainly the large technology platforms, without any guarantee of a fairer sharing of the value and impact generated as originally intended".

For all of the above, organisations such as Open Future have been advocating for several years now for Artificial Intelligence to function as a common good, managed and developed as a digital public infrastructure for the benefit of all, avoiding the concentration of power and promoting equity and transparency in both its development and its application.

To this end, they propose a set of principles to guide the governance of the data commons in its application for AI training so as to maximise the value generated for society and minimise the possibilities of potential abuse by commercial interests:

- Share as much data as possible, while maintaining such restrictions as may be necessary to preserve individual and collective rights.

- Be fully transparent and provide all existing documentation on the data, as well as on its use, and clearly distinguish between real and synthetic data.

- Respect decisions made about the use of data by persons who have previously contributed to the creation of the data, either through the transfer of their own data or through the development of new content, including respect for any existing legal framework.

- Protect the common benefit in the use of data and a sustainable use of data in order to ensure proper governance over time, always recognising its relational and collective nature.

- Ensuring the quality of data, which is critical to preserving its value as a common good, especially given the potential risks of contamination associated with its use by AI.

- Establish trusted institutions that are responsible for data governance and facilitate participation by the entire data community, thus going a step beyond the existing models for data intermediaries.

Use cases and applications

There are currently many real-world examples that help illustrate the transformative potential of data commons:

- Health data commons : projects such as the National Institutes of Health's initiative in the United States - NIH Common Fund to analyse and share large biomedical datasets, or the National Cancer Institute's Cancer Research Data Commons , demonstrate how data commons can contribute to the acceleration of health research and innovation.

- AI training and machine learning: the evaluation of AI systems depends on rigorous and standardised test data sets. Initiatives such as OpenML or MLCommons build open, large-scale and diverse datasets, helping the wider community to deliver more accurate and secure AI systems.

- Urban and mobility data commons : cities that take advantage of shared urban data platforms improve decision-making and public services through collective data analysis, as is the case of Barcelona Dades, which in addition to a large repository of open data integrates and disseminates data and analysis on the demographic, economic, social and political evolution of the city. Other initiatives such as OpenStreetMaps itself can also contribute to providing freely accessible geographic data.

- Culture and knowledge preservation: with such relevant initiatives in this field as Mozilla's Common Voice project to preserve and revitalise the world's languages, or Wikidata, which aims to provide structured access to all data from Wikimedia projects, including the popular Wikipedia.

Challenges in the data commons

Despite their promise and potential as a transformative tool for new challenges in the digital age, the data commons also face their own challenges:

- Complexity in governance: Striking the right balance between inclusion, control and privacy can be a delicate task.

- Sustainability: Many of the existing data commons are fighting an ongoing battle to try to secure the funding and resources they need to sustain themselves and ensure their long-term survival.

- Legal and ethical issues: addressing challenges relating to intellectual property rights, data ownership and ethical use remain critical issues that have yet to be fully resolved.

- Interoperability: Ensuring compatibility between datasets and platforms is a persistent technical hurdle in almost any data sharing initiative, and the data commons were to be no exception.

The way forward

To unlock their full potential, the data commons require collective action and a determined commitment to innovation. Key actions include:

- Develop standardised governance models that strike a balance between ethical considerations and technical requirements.

- Apply the principle of reciprocity in the use of data, requiring those who benefit from it to share their results back with the community.

- Protection of sensitive data through anonymisation, preventing data from being used for mass surveillance or discrimination.

- Encourage investment in infrastructure to support scalable and sustainable data exchange.

- Promote awareness of the social benefits of data commons to encourage participation and collaboration.

Policy makers, researchers and civil society organisations should work together to create an ecosystem in which the data commons can thrive, fostering more equitable growth in the digital economy and ensuring that the data commons can benefit all.

Conclusion

The data commons can be a powerful tool for democratising access to data and fostering innovation. In this era defined by AI and digital transformation, they offer us an alternative path to equitable, sustainable and inclusive progress. Addressing its challenges and adopting a collaborative governance approach through cooperation between communities, researchers and regulators will ensure fair and responsible use of data.

This will ensure that data commons become a fundamental pillar of the digital future, including new applications of Artificial Intelligence, and could also serve as a key enabling tool for some of the key actions that are part of the recently announced European competitiveness compass, such as the new Data Union strategy and the AI Gigafactories initiative.

Content prepared by Carlos Iglesias, Open data Researcher and consultant, World Wide Web Foundation. The contents and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Open data portals are an invaluable source of public information. However, extracting meaningful insights from this data can be challenging for users without advanced technical knowledge.

In this practical exercise, we will explore the development of a web application that democratizes access to this data through the use of artificial intelligence, allowing users to make queries in natural language.

The application, developed using the datos.gob.es portal as a data source, integrates modern technologies such as Streamlit for the user interface and Google's Gemini language model for natural language processing. The modular nature allows any Artificial Intelligence model to be used with minimal changes. The complete project is available in the Github repository.

Access the data laboratory repository on Github.

Run the data preprocessing code on Google Colab.

In this video, the author explains what you will find both on Github and Google Colab.

Application Architecture

The core of the application is based on four main interconnected sections that work together to process user queries:

- Context Generation

- Analyzes the characteristics of the chosen dataset.

- Generates a detailed description including dimensions, data types, and statistics.

- Creates a structured template with specific guidelines for code generation.

- Context and Query Combination

- Combines the generated context with the user's question, creating the prompt that the artificial intelligence model will receive.

- Response Generation

- Sends the prompt to the model and obtains the Python code that allows solving the generated question.

- Code Execution

- Safely executes the generated code with a retry and automatic correction system.

- Captures and displays the results in the application frontend.

Figure 1. Request processing flow

Development Process

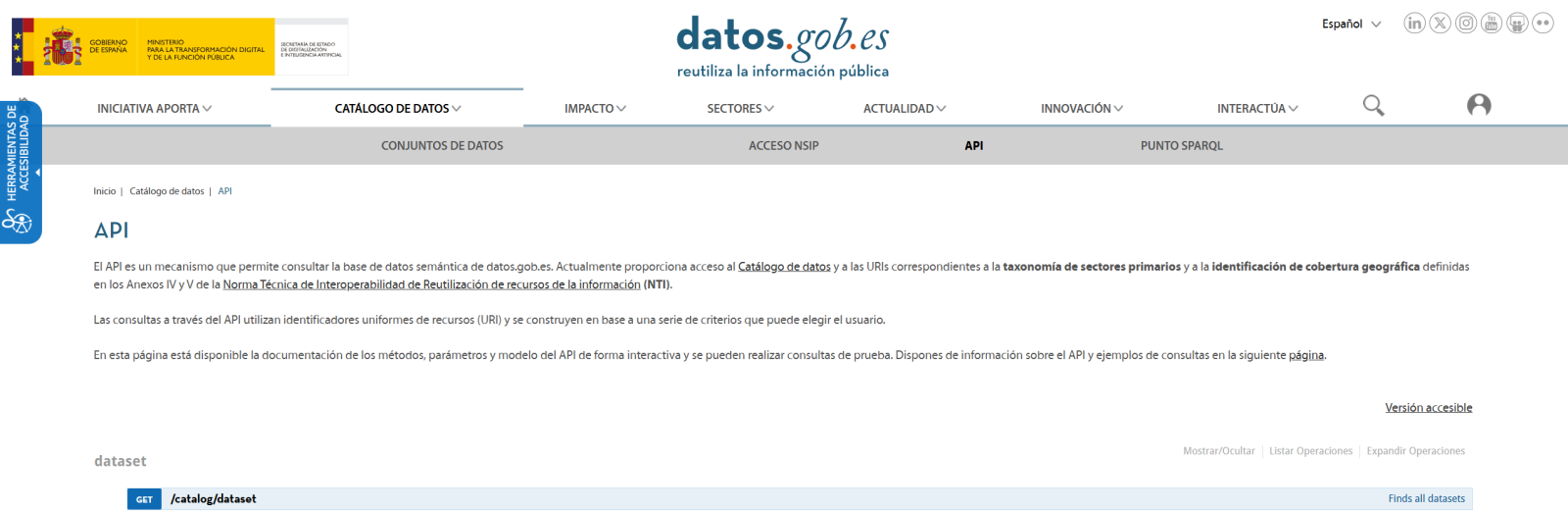

The first step is to establish a way to access public data. The datos.gob.es portal offers datasets via API. Functions have been developed to navigate the catalog and download these files efficiently.

Figura 2. API de datos.gob