We know that the open data managed by the public sector in the exercise of its functions is an invaluable resource for promoting transparency, driving innovation and stimulating economic development. At the global level, in the last 15 years this idea has led to the creation of data portals that serve as a single point of access for public information both in a country, a region or city.

However, we sometimes find that the full exploitation of the potential of open data is limited by problems inherent in its quality. Inconsistencies, lack of standardization or interoperability, and incomplete metadata are just some of the common challenges that sometimes undermine the usefulness of open datasets and that government agencies also point to as the main obstacle to AI adoption.

When we talk about the relationship between open data and artificial intelligence, we almost always start from the same idea: open data feeds AI, that is, it is part of the fuel for models. Whether it's to train foundational models like ALIA, to specialize small language models (SLMs) versus LLMs, or to evaluate and validate their capabilities or explain their behavior (XAI), the argument revolves around the usefulness of open data for artificial intelligence, forgetting that open data was already there and has many other uses.

Therefore, we are going to reverse the perspective and explore how AI itself can become a powerful tool to improve the quality and, therefore, the value of open data itself. This approach, which was already outlined by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) in its pioneering 2022 Machine Learning for Official Statistics report , has become more relevant since the explosion of generative AI. We can now use the artificial intelligence available to increase the quality of datasets that are published throughout their entire lifecycle: from capture and normalization to validation, anonymization, documentation, and follow-up in production.

With this, we can increase the public value of data, contribute to its reuse and amplify its social and economic impact. And, at the same time, to improve the quality of the next generation of artificial intelligence models.

Common challenges in open data quality

Data quality has traditionally been a Critical factor for the success of any open data initiative, which is cited in numerous reports such as that of the European Commission "Improving data publishing by open data portal managers and owners”. The most frequent challenges faced by data publishers include:

-

Inconsistencies and errors: Duplicate data, heterogeneous formats, or outliers are common in datasets. Correcting these small errors, ideally at the data source itself, was traditionally costly and greatly limited the usefulness of many datasets.

-

Lack of standardization and interoperability: Two sets that talk about the same thing may name columns differently, use non-comparable classifications, or lack persistent identifiers to link entities. Without a common minimum, combining sources becomes an artisanal work that makes it more expensive to reuse data.

- Incomplete or inaccurate metadata: The lack of clear information about the origin, collection methodology, frequency of updating or meaning of the fields, complicates the understanding and use of the data. For example, knowing with certainty if the resource can be integrated into a service, if it is up to date or if there is a point of contact to resolve doubts is very important for its reuse.

- Outdated or outdated data: In highly dynamic domains such as mobility, pricing, or environmental data, an outdated set can lead to erroneous conclusions. And if there are no versions, changelogs, or freshness indicators, it's hard to know what's changed and why. The absence of a "history" of the data complicates auditing and reduces trust.

- Inherent biases: sometimes coverage is incomplete, certain populations are underrepresented, or a management practice introduces systematic deviation. If these limits are not documented and warned, analyses can reinforce inequalities or reach unfair conclusions without anyone noticing.

Where Artificial Intelligence Can Help

Fortunately, in its current state, artificial intelligence is already in a position to provide a set of tools that can help address some of these open data quality challenges, transforming your management from a manual and error-prone process to a more automated and efficient one:

- Automated error detection and correction: Machine learning algorithms and AI models can automatically and reliably identify inconsistencies, duplicates, outliers, and typos in large volumes of data. In addition, AI can help normalize and standardize data, transforming it for example into common formats and schemas to facilitate interoperability (such as DCAT-AP), and at a fraction of the cost it was so far.

- Metadata enrichment and cataloging: Technologies associated with natural language processing (NLP), including the use of large language models (LLMs) and small language models (SLMs), can help analyze descriptions and generate more complete and accurate metadata. This includes tasks such as suggesting relevant tags, classification categories, or extracting key entities (place names, organizations, etc.) from textual descriptions to enrich metadata.

- Anonymization and privacy: When open data contains information that could affect privacy, anonymization becomes a critical, but sometimes costly, task. Artificial Intelligence can contribute to making anonymization much more robust and to minimize risks related to re-identification by combining different data sets.

Bias assessment: AI can analyze the open datasets themselves for representation or historical biases. This allows publishers to take steps to correct them or at least warn users about their presence so that they are taken into account when they are to be reused. In short, artificial intelligence should not only be seen as a "consumer" of open data, but also as a strategic ally to improve its quality. When integrated with standards, processes, and human oversight, AI helps detect and explain incidents, better document sets, and publish trust-building quality evidence. As described in the 2024 Artificial Intelligence Strategy, this synergy unlocks more public value: it facilitates innovation, enables better-informed decisions, and consolidates a more robust and reliable open data ecosystem with more useful, more reliable open data with greater social impact.

In addition, a virtuous cycle is activated: higher quality open data trains more useful and secure models; and more capable models make it easier to continue raising the quality of data. In this way, data management is no longer a static task of publication and becomes a dynamic process of continuous improvement.

Content created by Jose Luis Marín, Senior Consultant in Data, Strategy, Innovation & Digitalisation. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a central technology in people's lives and in the strategy of companies. In just over a decade, we've gone from interacting with virtual assistants that understood simple commands, to seeing systems capable of writing entire reports, creating hyper-realistic images, or even writing code.

This visible leap has made many wonder: is it all the same? What is the difference between what we already knew as AI and this new "Generative AI" that is so much talked about?

In this article we are going to organize those ideas and explain, with clear examples, how "Traditional" AI and Generative AI fit under the great umbrella of artificial intelligence.

Traditional AI: analysis and prediction

For many years, what we understood by AI was closer to what we now call "Traditional AI". These systems are characterized by solving concrete, well-defined problems within a framework of available rules or data.

Some practical examples:

-

Recommendation engines: Spotify suggests songs based on your listening history and Netflix adjusts its catalog to your personal tastes, generating up to 80% of views on the platform.

-

Prediction systems: Walmart uses predictive models to anticipate the demand for products based on factors such as weather or local events; Red Eléctrica de España applies similar algorithms to forecast electricity consumption and balance the grid.

- Automatic recognition: Google Photos classifies images by recognizing faces and objects; Visa and Mastercard use anomaly detection models to identify fraud in real time; Tools like Otter.ai automatically transcribe meetings and calls.

In all these cases, the models learn from past data to provide a classification, prediction, or decision. They do not invent anything new, but recognize patterns and apply them to the future.

Generative AI: content creation

The novelty of generative AI is that it not only analyzes, but also produces (generates) from the data it has.

In practice, this means that:

-

You can generate structured text from a couple of initial ideas.

-

You can combine existing visual elements from a written description.

-

You can create product prototypes, draft presentations, or propose code snippets based on learned patterns.

The key is that generative models don't just classify or predict, they generate new combinations based on what they learned during their training.

The impact of this breakthrough is enormous: in the development world, GitHub Copilot already includes agents that detect and fix programming errors on their own; in design, Google's Nano Banana tool promises to revolutionize image editing with an efficiency that could render programs like Photoshop obsolete; and in music, entirely AI-created bands like Velvet Velvet Sundown they already exceed one million monthly listeners on Spotify, with songs, images and biography fully generated, without real musicians behind them.

When is it best to use each type of AI?

The choice between Traditional and Generative AI is not a matter of fashion, but of what specific need you want to solve. Each shines in different situations:

Traditional AI: the best option when...

-

You need to predict future behaviors based on historical data (sales, energy consumption, predictive maintenance).

-

You want to detect anomalies or classify information accurately (transaction fraud, imaging, spam).

-

You are looking to optimize processes to gain efficiency (logistics, transport routes, inventory management).

-

You work in critical environments where reliability and accuracy are a must (health, energy, finance).

Use it when the goal is to make decisions based on real data with the highest possible accuracy.

Generative AI: the best option when...

-

You need to create content (texts, images, music, videos, code).

-

You want to prototype or experiment quickly, exploring different scenarios before deciding (product design, R+D testing).

-

You are looking for more natural interaction with users (chatbots, virtual assistants, conversational interfaces).

-

You require large-scale personalization, generating messages or materials adapted to each individual (marketing, training, education).

-

You are interested in simulating scenarios that you cannot easily obtain with real data (fictitious clinical cases, synthetic data to train other models).

Use it when the goal is to create, personalize, or interact in a more human and flexible way.

An example from the health field illustrates this well:

-

Traditional AI can analyze thousands of clinical records to anticipate the likelihood of a patient developing a disease.

-

Generative AI can create fictional scenarios to train medical students, generating realistic clinical cases without exposing real patient data.

Do they compete or complement each other?

In 2019, Gartner introduced the concept of Composite AI to describe hybrid solutions that combined different AI approaches to solve a problem more comprehensively. Although it was a term that was not very widespread then, today it is more relevant than ever thanks to the emergence of Generative AI.

Generative AI does not replace Traditional AI, but rather complements it. When you integrate both approaches into a single workflow, you achieve much more powerful results than if you used each technology separately.

Although, according to Gartner, Composite AI is still in the Innovation Trigger phase, where an emerging technology begins to generate interest, and although its practical use is still limited, we already see many new trends being generated in multiple sectors:

-

In retail: A traditional system predicts how many orders a store will receive next week, and generative AI automatically generates personalized product descriptions for customers of those orders.

-

In education: a traditional model assesses student progress and detects weak areas, while generative AI designs exercises or materials tailored to those needs.

-

In industrial design: a traditional algorithm optimizes manufacturing logistics, while a generative AI proposes prototypes of new parts or products.

Ultimately, instead of questioning which type of AI is more advanced, the right thing to do is to ask: what problem do I want to solve, and which AI approach is right for it?

Content created by Juan Benavente, senior industrial engineer and expert in technologies related to the data economy. The content and views expressed in this publication are the sole responsability of the author.

From today, September 15, registration is open for one of the most important events in the geospatial sector in the Iberian Peninsula. The XVI Iberian Conference on Spatial Data Infrastructures (JIIDE 2025) will be held in Oviedo from 12 to 14 November 2025. This annual meeting represents a unique opportunity to explore the latest trends in spatial data reuse, especially in the context of the application of artificial intelligence to territorial knowledge.

Since its first edition in 2011, the JIIDEs have evolved as a result of collaboration between the Direção-Geral do Território de Portugal, the National Geographic Institute of Spain through the National Center for Geographic Information, and the Government of Andorra. In this sixteenth edition, the Ministry of Territorial Planning, Urban Planning, Housing and Citizens' Rights of the Principality of Asturias and the University of Oviedo also join, thus consolidating an initiative that brings together hundreds of professionals from the Public Administration, the private sector and the academic field every year.

For three days, experts with proven experience and technical knowledge in geographic information will share their most innovative developments, work methodologies and success stories in the management and reuse of spatial data.

Two axes: artificial intelligence and the INSPIRE and HVDS regulatory framework

The central theme of this edition, "AI and territory: exploring the new frontiers of spatial knowledge", reflects the natural evolution of the sector towards the incorporation of emerging technologies. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and advanced analytics algorithms are radically transforming the way we process, analyze, and extract value from geospatial data.

This orientation towards AI is not accidental. The publication and use of geospatial data makes it possible to harness one of the most valuable digital assets for economic development, environmental monitoring, competitiveness, innovation and job creation. When this data is combined with artificial intelligence techniques, its potential multiplies exponentially.

The conference takes place at a particularly relevant time for the open data ecosystem. The INSPIRE Directive, together with Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on open data and re-use of public sector information, has established a regulatory framework that explicitly recognises the economic and social value of digital geospatial data.

The evolution in the publication of high-value datasets marks an important milestone in this process. These sets, characterized by their great potential for reuse, should be available free of charge, in machine-readable formats and through application programming interfaces (APIs). Geospatial data occupies a central position in this categorisation, underlining its strategic importance for the European open data ecosystem.

JIIDE 2025 will devote particular attention to presenting practical examples of re-use of these high-value datasets , both through the new OGC APIs and through traditional download services and established interoperable formats. This practical approach will allow attendees to learn about real cases of implementation and their tangible results.

Miscellaneous Program: Use Cases, AI, and Geospatial Data Reuse

You can also check the program here. Among the planned activities, there are sessions ranging from fundamental technical aspects to innovative applications that demonstrate the transformative potential of this data. The activities are organized into five main themes:

Spatial data structure and metadata.

Data management and publication.

Development of spatial software.

Artificial intelligence.

Cooperation between agents.

Some of the highlighted topics are project management and coordination, where corporate systems such as the SIG of the Junta de Andalucía or the SITNA of the Government of Navarra will be presented. Earth observation will also feature prominently, with presentations on the evolution of the National Plan for Aerial Orthophotography (APNOA) programme and advanced deep learning image processing techniques.

On the other hand, thematic visualisers also represent another fundamental axis, showing how spatial data can be transformed into accessible tools for citizens. From eclipse visualizers to tools for calculating the solar potential of rooftops, developments will be presented that demonstrate how the creative reuse of data can generate services of high social value.

Following the annual theme, the application of AI to geospatial data will be approached from multiple perspectives. Use cases will be presented in areas as diverse as the automatic detection of sports facilities, the classification of LiDAR point clouds, the identification of hazardous materials such as asbestos, or the optimization of urban mobility.

One of the most relevant sessions for the open data community will focus specifically on "Reuse and Open Government". This session will address the integration of spatial data infrastructures into open data portals, spatial data metadata according to the GeoDCAT-AP standard, and the application of data quality regulations.

Local governments play a key role in the generation and publication of spatial data. For this reason, the JIIDE 2025 will dedicate a specific session to the publication of local data, where municipalities such as Barcelona, Madrid, Bilbao or Cáceres will share their experiences and developments.

In addition to the theoretical sessions, the conferences include practical workshops on specific tools, methodologies and technologies. These workshops, lasting 45 minutes to an hour, allow attendees to experiment directly with the solutions presented. Some of them address the creation of custom web geoportals and others, for example, the implementation of OGC APIs, through advanced visualization techniques and metadata management tools.

Participate in person or online

The JIIDEs maintain their commitment to open participation, inviting both researchers and professionals to present their tools, technical solutions, work methodologies and success stories. In addition, the JIIDE 2025 will be held in hybrid mode, allowing both face-to-face participation in Oviedo and virtual monitoring.

This flexibility, maintained from the experiences of recent years, ensures that professionals throughout the Iberian territory and beyond can benefit from shared knowledge. Participation remains free, although prior registration is required for each session, roundtable or workshop.

Starting today, you can sign up and take advantage of this opportunity to learn and exchange experiences on geospatial data. Registration is available on the official website of the event: https://www.jiide.org/web/portal/inicio

Synthetic images are visual representations artificially generated by algorithms and computational techniques, rather than being captured directly from reality with cameras or sensors. They are produced from different methods, among which the antagonistic generative networks (Generative Adversarial NetworksGAN), the Dissemination models, and the 3D rendering techniques. All of them allow you to create images of realistic appearance that in many cases are indistinguishable from an authentic photograph.

When this concept is transferred to the field of Earth observation, we are talking about synthetic satellite images. These are not obtained from a space sensor that captures real electromagnetic radiation, but are generated digitally to simulate what a satellite would see from orbit. In other words, instead of directly reflecting the physical state of the terrain or atmosphere at a particular time, they are computational constructs capable of mimicking the appearance of a real satellite image.

The development of this type of image responds to practical needs. Artificial intelligence systems that process remote sensing data require very large and varied sets of images. Synthetic images allow, for example, to recreate areas of the Earth that are little observed, to simulate natural disasters – such as forest fires, floods or droughts – or to generate specific conditions that are difficult or expensive to capture in practice. In this way, they constitute a valuable resource for training detection and prediction algorithms in agriculture, emergency management, urban planning or environmental monitoring.

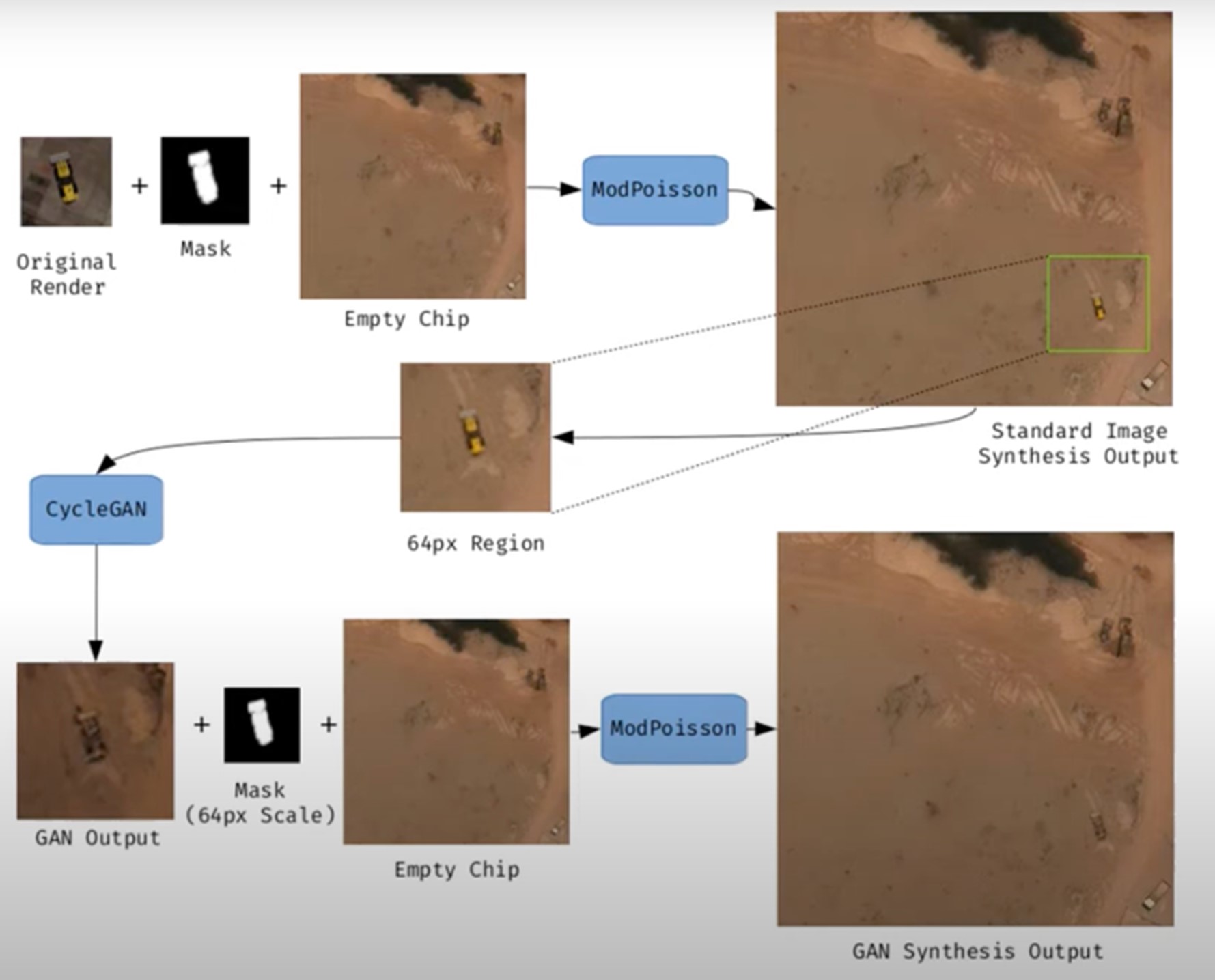

Figure 1. Example of synthetic satellite image generation.

Its value is not limited to model training. Where high-resolution images do not exist – due to technical limitations, access restrictions or economic reasons – synthesis makes it possible to fill information gaps and facilitate preliminary studies. For example, researchers can work with approximate synthetic images to design risk models or simulations before actual data are available.

However, synthetic satellite imagery also poses significant risks. The possibility of generating very realistic scenes opens the door to manipulation and misinformation. In a geopolitical context, an image showing non-existent troops or destroyed infrastructure could influence strategic decisions or international public opinion. In the environmental field, manipulated images could be disseminated to exaggerate or minimize the impacts of phenomena such as deforestation or melting ice, with direct effects on policies and markets.

Therefore, it is convenient to differentiate between two very different uses. The first is use as a support, when synthetic images complement real images to train models or perform simulations. The second is use as a fake, when they are deliberately presented as authentic images in order to deceive. While the former uses drive innovation, the latter threatens trust in satellite data and poses an urgent challenge of authenticity and governance.

Risks of satellite imagery applied to Earth observation

Synthetic satellite imagery poses significant risks when used in place of images captured by real sensors. Below are examples that demonstrate this.

A new front of disinformation: "deepfake geography"

The term deepfake geography has already been consolidated in the academic and popular literature to describe fictitious satellite images, manipulated with AI, that appear authentic, but do not reflect any existing reality. Research from the University of Washington, led by Bo Zhao, used algorithms such as CycleGAN to modify images of real cities—for example, altering the appearance of Seattle with non-existent buildings or transforming Beijing into green areas—highlighting the potential to generate convincing false landscapes.

One OnGeo Intelligence (OGC) platform article stresses that these images are not purely theoretical, but real threats affecting national security, journalism and humanitarian work. For its part, the OGC warns that fabricated satellite imagery, AI-generated urban models, and synthetic road networks have already been observed, and that they pose real challenges to public and operational trust.

Strategic and policy implications

Satellite images are considered "impartial eyes" on the planet, used by governments, media and organizations. When these images are faked, their consequences can be severe:

- National security and defense: if false infrastructures are presented or real ones are hidden, strategic analyses can be diverted or mistaken military decisions can be induced.

- Disinformation in conflicts or humanitarian crises: An altered image showing fake fires, floods, or troop movements can alter the international response, aid flows, or citizens' perceptions, especially if it is spread through social media or media without verification.

- Manipulation of realistic images of places: not only the general images are at stake. Nguyen et al. (2024) showed that it is possible to generate highly realistic synthetic satellite images of very specific facilities such as nuclear plants.

Crisis of trust and erosion of truth

For decades, satellite imagery has been perceived as one of the most objective and reliable sources of information about our planet. They were the graphic evidence that made it possible to confirm environmental phenomena, follow armed conflicts or evaluate the impact of natural disasters. In many cases, these images were used as "unbiased evidence," difficult to manipulate, and easy to validate. However, the emergence of synthetic images generated by artificial intelligence has begun to call into question that almost unshakable trust.

Today, when a satellite image can be falsified with great realism, a profound risk arises: the erosion of truth and the emergence of a crisis of confidence in spatial data.

The breakdown of public trust

When citizens can no longer distinguish between a real image and a fabricated one, trust in information sources is broken. The consequence is twofold:

- Distrust of institutions: if false images of a fire, a catastrophe or a military deployment circulate and then turn out to be synthetic, citizens may also begin to doubt the authentic images published by space agencies or the media. This "wolf is coming" effect generates skepticism even in the face of legitimate evidence.

- Effect on journalism: traditional media, which have historically used satellite imagery as an unquestionable visual source, risk losing credibility if they publish doctored images without verification. At the same time, the abundance of fake images on social media erodes the ability to distinguish what is real and what is not.

- Deliberate confusion: in contexts of disinformation, the mere suspicion that an image may be false can already be enough to generate doubt and sow confusion, even if the original image is completely authentic.

The following is a summary of the possible cases of manipulation and risk in satellite images:

|

Ambit |

Type of handling |

Main risk |

Documented example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Armed conflicts | Insertion or elimination of military infrastructures. | Strategic disinformation; erroneous military decisions; loss of credibility in international observation. | Alterations demonstrated in deepfake geography studies where dummy roads, bridges or buildings were added to satellite images. |

| Climate change and the environment | Alteration of glaciers, deforestation or emissions. | Manipulation of environmental policies; delay in measures against climate change; denialism. | Studies have shown the ability to generate modified landscapes (forests in urban areas, changes in ice) by means of GANs. |

| Gestión de emergencias | Creation of non-existent disasters (fires, floods). | Misuse of resources in emergencies; chaos in evacuations; loss of trust in agencies. | Research has shown the ease of inserting smoke, fire or water into satellite images. |

| Mercados y seguros | Falsification of damage to infrastructure or crops. | Financial impact; massive fraud; complex legal litigation. | Potential use of fake images to exaggerate damage after disasters and claim compensation or insurance. |

| Derechos humanos y justicia internacional | Alteration of visual evidence of war crimes. | Delegitimization of international tribunals; manipulation of public opinion. | Risk identified in intelligence reports: Doctored images could be used to accuse or exonerate actors in conflicts. |

| Geopolítica y diplomacia | Creation of fictitious cities or border changes. | Diplomatic tensions; treaty questioning; State propaganda | Examples of deepfake maps that transform geographical features of cities such as Seattle or Tacoma. |

Figure 2. Table showing possible cases of manipulation and risk in satellite images

Impact on decision-making and public policies

The consequences of relying on doctored images go far beyond the media arena:

- Urbanism and planning: decisions about where to build infrastructure or how to plan urban areas could be made on manipulated images, generating costly errors that are difficult to reverse.

- Emergency management: If a flood or fire is depicted in fake images, emergency teams can allocate resources to the wrong places, while neglecting areas that are actually affected.

- Climate change and the environment: Doctored images of glaciers, deforestation or polluting emissions could manipulate political debates and delay the implementation of urgent measures.

- Markets and insurance: Insurers and financial companies that rely on satellite imagery to assess damage could be misled, with significant economic consequences.

In all these cases, what is at stake is not only the quality of the information, but also the effectiveness and legitimacy of public policies based on that data.

The technological cat and mouse game

The dynamics of counterfeit generation and detection are already known in other areas, such as video or audio deepfakes: every time a more realistic generation method emerges, a more advanced detection algorithm is developed, and vice versa. In the field of satellite images, this technological career has particularities:

- Increasingly sophisticated generators: today's broadcast models can create highly realistic scenes, integrating ground textures, shadows, and urban geometries that fool even human experts.

- Detection limitations: Although algorithms are developed to identify fakes (analyzing pixel patterns, inconsistencies in shadows, or metadata), these methods are not always reliable when faced with state-of-the-art generators.

- Cost of verification: independently verifying a satellite image requires access to alternative sources or different sensors, something that is not always available to journalists, NGOs or citizens.

- Double-edged swords: The same techniques used to detect fakes can be exploited by those who generate them, further refining synthetic images and making them more difficult to differentiate.

From visual evidence to questioned evidence

The deeper impact is cultural and epistemological: what was previously assumed to be objective evidence now becomes an element subject to doubt. If satellite imagery is no longer perceived as reliable evidence, it weakens fundamental narratives around scientific truth, international justice, and political accountability.

- In armed conflicts, a satellite image showing possible war crimes can be dismissed under the accusation of being a deepfake.

- In international courts, evidence based on satellite observation could lose weight in the face of suspicion of manipulation.

- In public debate, the relativism of "everything can be false" can be used as a rhetorical weapon to delegitimize even the strongest evidence.

Strategies to ensure authenticity

The crisis of confidence in satellite imagery is not an isolated problem in the geospatial sector, but is part of a broader phenomenon: digital disinformation in the age of artificial intelligence. Just as video deepfakes have called into question the validity of audiovisual evidence, the proliferation of synthetic satellite imagery threatens to weaken the last frontier of perceived objective data: the unbiased view from space.

Ensuring the authenticity of these images requires a combination of technical solutions and governance mechanisms, capable of strengthening traceability, transparency and accountability across the spatial data value chain. The main strategies under development are described below.

Robust metadata: Record origin and chain of custody

Metadata is the first line of defense against manipulation. In satellite imagery, they should include detailed information about:

- The sensor used (type, resolution, orbit).

- The exact time of acquisition (date and time, with time precision).

- The precise geographical location (official reference systems).

- The applied processing chain (atmospheric corrections, calibrations, reprojections).

Recording this metadata in secure repositories allows the chain of custody to be reconstructed, i.e. the history of who, how and when an image has been manipulated. Without this traceability, it is impossible to distinguish between authentic and counterfeit images.

EXAMPLE: The European Union's Copernicus program already implements standardized and open metadata for all its Sentinel images, facilitating subsequent audits and confidence in the origin.

Digital signatures and blockchain: ensuring integrity

Digital signatures allow you to verify that an image has not been altered since it was captured. They function as a cryptographic seal that is applied at the time of acquisition and validated at each subsequent use.

Blockchain technology offers an additional level of assurance: storing acquisition and modification records on an immutable chain of blocks. In this way, any changes in the image or its metadata would be recorded and easily detectable.

EXAMPLE: The ESA – Trusted Data Framework project explores the use of blockchain to protect the integrity of Earth observation data and bolster trust in critical applications such as climate change and food security.

Invisible watermarks: hidden signs in the image

Digital watermarking involves embedding imperceptible signals in the satellite image itself, so that any subsequent alterations can be detected automatically.

- It can be done at the pixel level, slightly modifying color patterns or luminance.

- It is combined with cryptographic techniques to reinforce its validity.

- It allows you to validate images even if they have been cropped, compressed, or reprocessed.

EXAMPLE: In the audiovisual sector, watermarks have been used for years in the protection of digital content. Its adaptation to satellite images is in the experimental phase, but it could become a standard verification tool.

Open Standards (OGC, ISO): Trust through Interoperability

Standardization is key to ensuring that technical solutions are applied in a coordinated and global manner.

- OGC (Open Geospatial Consortium) works on standards for metadata management, geospatial data traceability, and interoperability between systems. Their work on geospatial APIs and FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) metadata is essential to establishing common trust practices.

- ISO develops standards on information management and authenticity of digital records that can also be applied to satellite imagery.

EXAMPLE: OGC Testbed-19 included specific experiments on geospatial data authenticity, testing approaches such as digital signatures and certificates of provenance.

Cross-check: combining multiple sources

A basic principle for detecting counterfeits is to contrast sources. In the case of satellite imagery, this involves:

- Compare images from different satellites (e.g. Sentinel-2 vs. Landsat-9).

- Use different types of sensors (optical, radar SAR, hyperspectral).

- Analyze time series to verify consistency over time.

EXAMPLE: Damage verification in Ukraine following the start of the Russian invasion in 2022 was done by comparing images from several vendors (Maxar, Planet, Sentinel), ensuring that the findings were not based on a single source.

AI vs. AI: Automatic Counterfeit Detection

The same artificial intelligence that allows synthetic images to be created can be used to detect them. Techniques include:

- Pixel Forensics: Identify patterns generated by GANs or broadcast models.

- Neural networks trained to distinguish between real and synthetic images based on textures or spectral distributions.

- Geometric inconsistencies models: detect impossible shadows, topographic inconsistencies, or repetitive patterns.

EXAMPLE: Researchers at the University of Washington and other groups have shown that specific algorithms can detect satellite fakes with greater than 90% accuracy under controlled conditions.

Current Experiences: Global Initiatives

Several international projects are already working on mechanisms to reinforce authenticity:

- Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA): A partnership between Adobe, Microsoft, BBC, Intel, and other organizations to develop an open standard for provenance and authenticity of digital content, including images. Its model can be applied directly to the satellite sector.

- OGC work: the organization promotes the debate on trust in geospatial data and has highlighted the importance of ensuring the traceability of synthetic and real satellite images (OGC Blog).

- NGA (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) in the US has publicly acknowledged the threat of synthetic imagery in defence and is driving collaborations with academia and industry to develop detection systems.

Towards an ecosystem of trust

The strategies described should not be understood as alternatives, but as complementary layers in a trusted ecosystem:

|

Id |

Layers |

Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Robust metadata (source, sensor, chain of custody) |

Traceability guaranteed |

| 2 | Digital signatures and blockchain (data integrity) |

Ensuring integrity |

| 3 | Invisible watermarks (hidden signs) |

Add a hidden level of protection |

| 4 | Cross-check (multiple satellites and sensors) |

Validates independently |

| 5 | AI vs. AI (counterfeit detector) |

Respond to emerging threats |

| 6 | International governance (accountability, legal frameworks) |

Articulate clear rules of liability |

Figure 3. Layers to ensure confidence in synthetic satellite images

Success will depend on these mechanisms being integrated together, under open and collaborative frameworks, and with the active involvement of space agencies, governments, the private sector and the scientific community.

Conclusions

Synthetic images, far from being just a threat, represent a powerful tool that, when used well, can provide significant value in areas such as simulation, algorithm training or innovation in digital services. The problem arises when these images are presented as real without proper transparency, fueling misinformation or manipulating public perception.

The challenge, therefore, is twofold: to take advantage of the opportunities offered by the synthesis of visual data to advance science, technology and management, and to minimize the risks associated with the misuse of these capabilities, especially in the form of deepfakes or deliberate falsifications.

In the particular case of satellite imagery, trust takes on a strategic dimension. Critical decisions in national security, disaster response, environmental policy, and international justice depend on them. If the authenticity of these images is called into question, not only the reliability of the data is compromised, but also the legitimacy of decisions based on them.

The future of Earth observation will be shaped by our ability to ensure authenticity, transparency and traceability across the value chain: from data acquisition to dissemination and end use. Technical solutions (robust metadata, digital signatures, blockchain, watermarks, cross-verification, and AI for counterfeit detection), combined with governance frameworks and international cooperation, will be the key to building an ecosystem of trust.

In short, we must assume a simple but forceful guiding principle:

"If we can't trust what we see from space, we put our decisions on Earth at risk."

Content prepared by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Artificial intelligence (AI) assistants are already part of our daily lives: we ask them the time, how to get to a certain place or we ask them to play our favorite song. And although AI, in the future, may offer us infinite functionalities, we must not forget that linguistic diversity is still a pending issue.

In Spain, where Spanish coexists with co-official languages such as Basque, Catalan, Valencian and Galician, this issue is especially relevant. The survival and vitality of these languages in the digital age depends, to a large extent, on their ability to adapt and be present in emerging technologies. Currently, most virtual assistants, automatic translators or voice recognition systems do not understand all the co-official languages. However, did you know that there are collaborative projects to ensure linguistic diversity?

In this post we tell you about the approach and the greatest advances of some initiatives that are building the digital foundations necessary for the co-official languages in Spain to also thrive in the era of artificial intelligence.

ILENIA, the coordinator of multilingual resource initiatives in Spain

The models that we are going to see in this post share a focus because they are part of ILENIA, a state-level coordinator that connects the individual efforts of the autonomous communities. This initiative brings together the projects BSC-CNS (AINA), CENID (VIVES), HiTZ (NEL-GAITU) and the University of Santiago de Compostela (NÓS), with the aim of generating digital resources that allow the development of multilingual applications in the different languages of Spain.

The success of these initiatives depends fundamentally on citizen participation. Through platforms such as Mozilla's Common Voice, any speaker can contribute to the construction of these linguistic resources through different forms of collaboration:

- Spoken Read: Collecting different ways of speaking through voice donations of a specific text.

- Spontaneous speech: creates real and organic datasets as a result of conversations with prompts.

- Text in language: collaborate in the transcription of audios or in the contribution of textual content, suggesting new phrases or questions to enrich the corpora.

All resources are published under free licenses such as CC0, allowing them to be used free of charge by researchers, developers and companies.

The challenge of linguistic diversity in the digital age

Artificial intelligence systems learn from the data they receive during their training. To develop technologies that work correctly in a specific language, it is essential to have large volumes of data: audio recordings, text corpora and examples of real use of the language.

In other publications of datos.gob.es we have addressed the functioning of foundational models and initiatives in Spanish such as ALIA, trained with large corpus of text such as those of the Royal Spanish Academy.

Both posts explain why language data collection is not a cheap or easy task. Technology companies have invested massively in compiling these resources for languages with large numbers of speakers, but Spanish co-official languages face a structural disadvantage. This has led to many models not working properly or not being available in Valencian, Catalan, Basque or Galician.

However, there are collaborative and open data initiatives that allow the creation of quality language resources. These are the projects that several autonomous communities have launched, marking the way towards a multilingual digital future.

On the one hand, the Nós en Galicia Project creates oral and conversational resources in Galician with all the accents and dialectal variants to facilitate integration through tools such as GPS, voice assistants or ChatGPT. A similar purpose is that of Aina in Catalonia, which also offers an academic platform and a laboratory for developers or Vives in the Valencian Community. In the Basque Country there is also the Euskorpus project , which aims to constitute a quality text corpus in Basque. Let's look at each of them.

Proyecto Nós, a collaborative approach to digital Galician

The project has already developed three operational tools: a multilingual neural translator, a speech recognition system that converts speech into text, and a speech synthesis application. These resources are published under open licenses, guaranteeing their free and open access for researchers, developers and companies. These are its main features:

- Promoted by: the Xunta de Galicia and the University of Santiago de Compostela.

- Main objective: to create oral and conversational resources in Galician that capture the dialectal and accent diversity of the language.

- How to participate: The project accepts voluntary contributions both by reading texts and by answering spontaneous questions.

- Donate your voice in Galician: https://doagalego.nos.gal

Aina, towards an AI that understands and speaks Catalan

With a similar approach to the Nós project, Aina seeks to facilitate the integration of Catalan into artificial intelligence language models.

It is structured in two complementary aspects that maximize its impact:

- Aina Tech focuses on facilitating technology transfer to the business sector, providing the necessary tools to automatically translate websites, services and online businesses into Catalan.

- Aina Lab promotes the creation of a community of developers through initiatives such as Aina Challenge, promoting collaborative innovation in Catalan language technologies. Through this call , 22 proposals have already been selected with a total amount of 1 million to execute their projects.

The characteristics of the project are:

- Powered by: the Generalitat de Catalunya in collaboration with the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC-CNS).

- Main objective: it goes beyond the creation of tools, it seeks to build an open, transparent and responsible AI infrastructure with Catalan.

- How to participate: You can add comments, improvements, and suggestions through the contact inbox: https://form.typeform.com/to/KcjhThot?typeform-source=langtech-bsc.gitbook.io.

Vives, the collaborative project for AI in Valencian

On the other hand, Vives collects voices speaking in Valencian to serve as training for AI models.

- Promoted by: the Alicante Digital Intelligence Centre (CENID).

- Objective: It seeks to create massive corpora of text and voice, encourage citizen participation in data collection, and develop specialized linguistic models in sectors such as tourism and audiovisual, guaranteeing data privacy.

- How to participate: You can donate your voice through this link: https://vives.gplsi.es/instruccions/.

Gaitu: strategic investment in the digitalisation of the Basque language

In Basque, we can highlight Gaitu, which seeks to collect voices speaking in Basque in order to train AI models. Its characteristics are:

- Promoted by: HiTZ, the Basque language technology centre.

- Objective: to develop a corpus in Basque to train AI models.

- How to participate: You can donate your voice in Basque here https://commonvoice.mozilla.org/eu/speak.

Benefits of Building and Preserving Multilingual Language Models

The digitization projects of the co-official languages transcend the purely technological field to become tools for digital equity and cultural preservation. Its impact is manifested in multiple dimensions:

- For citizens: these resources ensure that speakers of all ages and levels of digital competence can interact with technology in their mother tongue, removing barriers that could exclude certain groups from the digital ecosystem.

- For the business sector: the availability of open language resources makes it easier for companies and developers to create products and services in these languages without assuming the high costs traditionally associated with the development of language technologies.

- For the research fabric, these corpora constitute a fundamental basis for the advancement of research in natural language processing and speech technologies, especially relevant for languages with less presence in international digital resources.

The success of these initiatives shows that it is possible to build a digital future where linguistic diversity is not an obstacle but a strength, and where technological innovation is put at the service of the preservation and promotion of linguistic cultural heritage.

In the field of data science, the ability to build robust predictive models is fundamental. However, a model is not just a set of algorithms; it is a tool that must be understood, validated, and ultimately useful for decision-making.

Thanks to the transparency and accessibility of open data, we have the unique opportunity to work in this exercise with real, updated, and institutional-quality information that reflects environmental issues. This democratization of access not only allows for the development of rigorous analyses with official data but also contributes to informed public debate on environmental policies, creating a direct bridge between scientific research and societal needs.

In this practical exercise, we will dive into the complete lifecycle of a modeling project, using a real case study: the analysis of air quality in Castile and León. Unlike approaches that focus solely on the implementation of algorithms, our methodology focuses on:

- Loading and initial data exploration: identifying patterns, anomalies, and underlying relationships that will guide our modeling.

- Exploratory analysis for modeling: building visualizations and performing feature engineering to optimize the model.

- Development and evaluation of regression models: building and comparing multiple iterative models to understand how complexity affects performance.

- Model application and conclusions: using the final model to simulate scenarios and quantify the impact of potential environmental policies.

Access the data laboratory repository on Github.

Run the data pre-processing code on Google Colab.

Analysis Architecture

The core of this exercise follows a structured flow in four key phases, as illustrated in Figure 1. Each phase builds on the previous one, from initial data exploration to the final application of the model.

Figure 1. Phases of the predictive modeling project.

Development Process

1. Loading and Initial Data Exploration

The first step is to understand the raw material of our analysis: the data. Using an air quality dataset from Castile and León, spanning 24 years of measurements, we face common real-world challenges:

- Missing Values: variables such as CO and PM2.5 have limited data coverage.

- Anomalous Data: negative and extreme values are detected, likely due to sensor errors.

Through a process of cleaning and transformation, we convert the raw data into a clean and structured dataset, ready for modeling.

2. Exploratory Analysis for Modeling

Once the data is clean, we look for patterns. Visual analysis reveals a strong seasonality in NO₂ levels, with peaks in winter and troughs in summer. This observation is crucial and leads us to create new variables (feature engineering), such as cyclical components for the months, which allow the model to "understand" the circular nature of the seasons.

Figure 2. Seasonal variation of NO₂ levels in Castile and León.

3. Development and Evaluation of Regression Models

With a solid understanding of the data, we proceed to build three linear regression models of increasing complexity:

- Base Model: uses only pollutants as predictors.

- Seasonal Model: adds time variables.

- Complete Model: includes interactions and geographical effects.

Comparing these models allows us to quantify the improvement in predictive capability. The Seasonal Model emerges as the optimal choice, explaining almost 63% of the variability in NO₂, a remarkable result for environmental data.

4. Model Application and Conclusions

Finally, we subject the model to a rigorous diagnosis and use it to simulate the impact of environmental policies. For example, our analysis estimates that a 20% reduction in NO emissions could translate into a 4.8% decrease in NO₂ levels.

Figure 3. Performance of the seasonal model. The predicted values align well with the actual values.

What can you learn?

This practical exercise allows you to learn:

- Data project lifecycle: from cleaning to application.

- Linear regression techniques: construction, interpretation, and diagnosis.

- Handling time-series data: capturing seasonality and trends.

- Model validation: techniques like cross-validation and temporal validation.

- Communicating results: how to translate findings into actionable insights.

Conclusions and Future

This exercise demonstrates the power of a structured and rigorous approach in data science. We have transformed a complex dataset into a predictive model that is not only accurate but also interpretable and useful.

For those interested in taking this analysis to the next level, the possibilities are numerous:

- Incorporation of meteorological data: variables such as temperature and wind could significantly improve accuracy.

- More advanced models: exploring techniques such as Generalized Additive Models (GAM) or other machine learning algorithms.

- Spatial analysis: investigating how pollution patterns vary between different locations.

In summary, this exercise not only illustrates the application of regression techniques but also underscores the importance of an integrated approach that combines statistical rigor with practical relevance.

Citizen participation in the collection of scientific data promotes a more democratic science, by involving society in R+D+i processes and reinforcing accountability. In this sense, there are a variety of citizen science initiatives launched by entities such as CSIC, CENEAM or CREAF, among others. In addition, there are currently numerous citizen science platform platforms that help anyone find, join and contribute to a wide variety of initiatives around the world, such as SciStarter.

Some references in national and European legislation

Different regulations, both at national and European level, highlight the importance of promoting citizen science projects as a fundamental component of open science. For example, Organic Law 2/2023, of 22 March, on the University System, establishes that universities will promote citizen science as a key instrument for generating shared knowledge and responding to social challenges, seeking not only to strengthen the link between science and society, but also to contribute to a more equitable, inclusive and sustainable territorial development.

On the other hand, Law 14/2011, of 1 June, on Science, Technology and Innovation, promotes "the participation of citizens in the scientific and technical process through, among other mechanisms, the definition of research agendas, the observation, collection and processing of data, the evaluation of impact in the selection of projects and the monitoring of results, and other processes of citizen participation."

At the European level, Regulation (EU) 2021/695 establishing the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation "Horizon Europe", indicates the opportunity to develop projects co-designed with citizens, endorsing citizen science as a research mechanism and a means of disseminating results.

Citizen science initiatives and data management plans

The first step in defining a citizen science initiative is usually to establish a research question that requires data collection that can be addressed with the collaboration of citizens. Then, an accessible protocol is designed for participants to collect or analyze data in a simple and reliable way (it could even be a gamified process). Training materials must be prepared and a means of participation (application, web or even paper) must be developed. It also plans how to communicate progress and results to citizens, encouraging their participation.

As it is an intensive activity in data collection, it is interesting that citizen science projects have a data management plan that defines the life cycle of data in research projects, that is, how data is created, organized, shared, reused and preserved in citizen science initiatives. However, most citizen science initiatives do not have such a plan: this recent research article found that only 38% of the citizen science projects consulted had a data management plan.

Figure 1. Data life cycle in citizen science projects Source: own elaboration – datos.gob.es.

On the other hand, data from citizen science only reach their full potential when they comply with the FAIR principles and are published in open access. In order to help have this data management plan that makes data from citizen science initiatives FAIR, it is necessary to have specific standards for citizen science such as PPSR Core.

Open Data for Citizen Science with the PPSR Core Standard

The publication of open data should be considered from the early stages of a citizen science project, incorporating the PPSR Core standard as a key piece. As we mentioned earlier, when research questions are formulated, in a citizen science initiative, a data management plan must be proposed that indicates what data to collect, in what format and with what metadata, as well as the needs for cleaning and quality assurance from the data collected by citizens. in addition to a publication schedule.

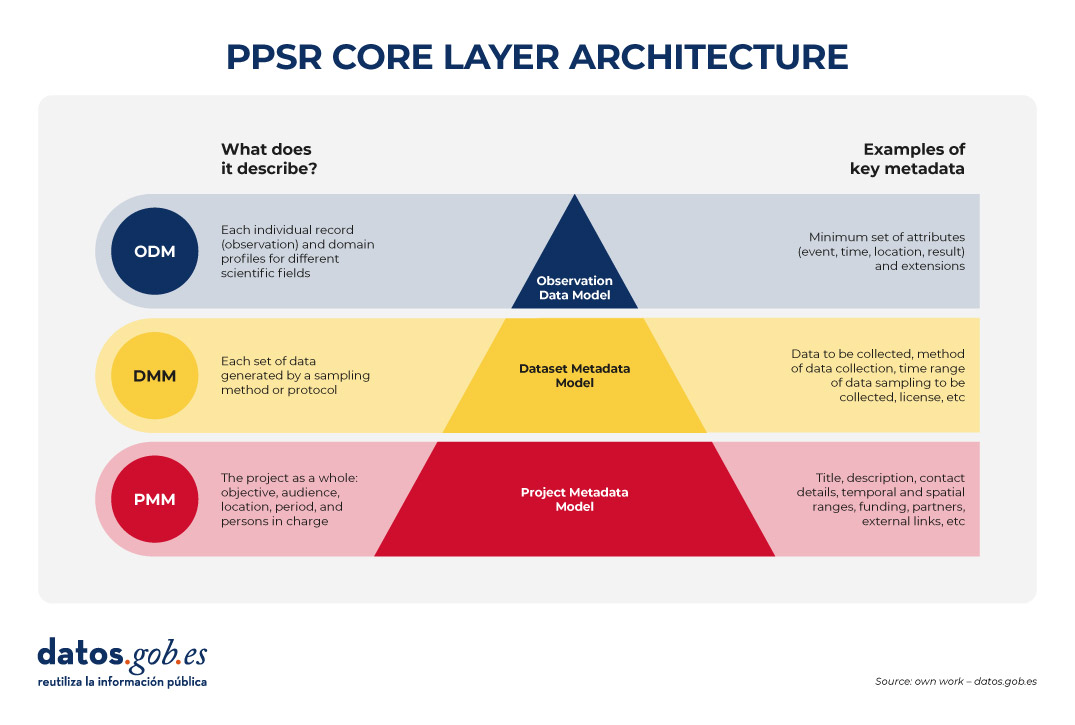

Then, it must be standardized with PPSR (Public Participation in Scientific Research) Core. PPSR Core is a set of data and metadata standards, specially designed to encourage citizen participation in scientific research processes. It has a three-layer architecture based on a Common Data Model (CDM). This CDM helps to organize in a coherent and connected way the information about citizen science projects, the related datasets and the observations that are part of them, in such a way that the CDM facilitates interoperability between citizen science platforms and scientific disciplines. This common model is structured in three main layers that allow the key elements of a citizen science project to be described in a structured and reusable way. The first is the Project Metadata Model (PMM), which collects the general information of the project, such as its objective, participating audience, location, duration, responsible persons, sources of funding or relevant links. Second, the Dataset Metadata Model (DMM) documents each dataset generated, detailing what type of information is collected, by what method, in what period, under what license and under what conditions of access. Finally, the Observation Data Model (ODM) focuses on each individual observation made by citizen science initiative participants, including the date and location of the observation and the result. It is interesting to note that this PPSR-Core layer model allows specific extensions to be added according to the scientific field, based on existing vocabularies such as Darwin Core (biodiversity) or ISO 19156 (sensor measurements). (ODM) focuses on each individual observation made by participants of the citizen science initiative, including the date and place of the observation and the outcome. It is interesting to note that this PPSR-Core layer model allows specific extensions to be added according to the scientific field, based on existing vocabularies such as Darwin Core (biodiversity) or ISO 19156 (sensor measurements).

Figure 2. PPSR CORE layering architecture. Source: own elaboration – datos.gob.es.

This separation allows a citizen science initiative to automatically federate the project file (PMM) with platforms such as SciStarter, share a dataset (DMM) with a institutional repository of open scientific data, such as those added in FECYT's RECOLECTA and, at the same time, send verified observations (ODMs) to a platform such as GBIF without redefining each field.

In addition, the use of PPSR Core provides a number of advantages for the management of the data of a citizen science initiative:

- Greater interoperability: platforms such as SciStarter already exchange metadata using PMM, so duplication of information is avoided.

- Multidisciplinary aggregation: ODM profiles allow datasets from different domains (e.g. air quality and health) to be united around common attributes, which is crucial for multidisciplinary studies.

- Alignment with FAIR principles: The required fields of the DMM are useful for citizen science datasets to comply with the FAIR principles.

It should be noted that PPSR Core allows you to add context to datasets obtained in citizen science initiatives. It is a good practice to translate the content of the PMM into language understandable by citizens, as well as to obtain a data dictionary from the DMM (description of each field and unit) and the mechanisms for transforming each record from the MDG. Finally, initiatives to improve PPSR Core can be highlighted, for example, through a DCAT profile for citizen science.

Conclusions

Planning the publication of open data from the beginning of a citizen science project is key to ensuring the quality and interoperability of the data generated, facilitating its reuse and maximizing the scientific and social impact of the project. To this end, PPSR Core offers a level-based standard (PMM, DMM, ODM) that connects the data generated by citizen science with various platforms, promoting that this data complies with the FAIR principles and considering, in an integrated way, various scientific disciplines. With PPSR Core , every citizen observation is easily converted into open data on which the scientific community can continue to build knowledge for the benefit of society.

Jose Norberto Mazón, Professor of Computer Languages and Systems at the University of Alicante. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

In an increasingly complex world, public decisions need more than intuition: they require scientific evidence. This is where I+P (Innovation + Public Policy) initiatives come into play: an intersection between creativity, data-driven knowledge, and policy action.

In this article we will explain this concept, including examples and information about funding programs.

What is I+P?

I+P is not a mathematical formula, but a strategic practice that combines scientific knowledge, research, and citizen participation to improve the formulation, implementation, and evaluation of public policies. It is not only a matter of applying technology to the public sphere, but of rethinking how decisions are made, how solutions are formulated and how society is involved in these processes through the application of scientific methodologies.

This idea stems from the concept of "science for public policy", also known as "science for policy" or "Science for Policy" (S4P) and implies active collaboration between public administrations and the scientific community.

I+P initiatives promote empirical evidence and experimentation. To this end, they promote the use of data, emerging technologies, pilot tests, agile methodologies and feedback loops that help design more efficient and effective policies, focused on the real needs of citizens. This facilitates real-time decision-making and the possibility of making agile adjustments in situations that require quick responses. In short, it is about providing more creative and accurate responses to today's challenges, such as climate change or digital inequality, areas where traditional policies can fall short.

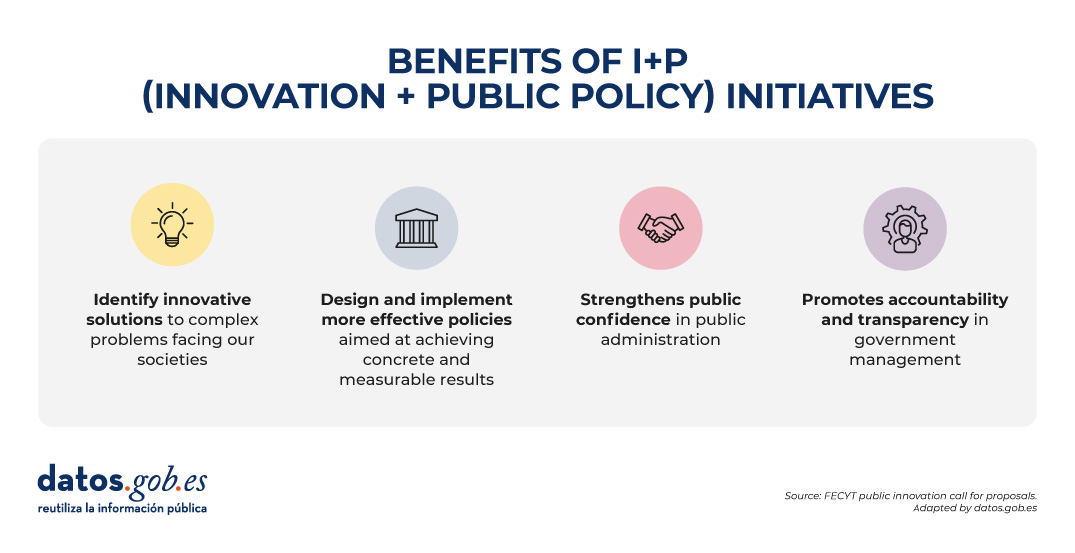

The following visual summarizes these and other benefits.

Source: FECYT Call for Public Innovation - adapted by datos.gob.es.

Examples of R+P initiatives

The use of data for political decision-making was evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, where policymakers were adapting the measures to be taken based on reports from institutions such as the World Health Organization (WHO). But beyond these types of extraordinary events, today we find consolidated initiatives that increasingly seek to promote innovation and decision-making based on scientific data in the public sphere on an ongoing basis. Let's look at two examples.

-

Periodic reports from scientific institutions to bring scientific knowledge closer to public decision-making

Scientific reports on topics such as climate change, bacterial resistance or food production are examples of how science can guide informed policy decisions.

The Science4Policy initiative of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) is an example of this. It is a collection of thematic reports that present solid evidence, generated in its research centers, on relevant social problems. Each report includes:

- An introduction to the problem and its social impact.

- Information on the research carried out by the CSIC on the subject.

- Conclusions and recommendations for public policies.

Its main objective is to transform scientific knowledge into accessible contributions for non-specialized audiences, thus facilitating informed decisions by public authorities.

-

Public innovation laboratories, a space for science-based creativity

Public innovation labs or GovLabs are experimental spaces that allow public employees, scientists, experts in various fields and citizens to co-create policies, prototype solutions and learn iteratively.

An example is the Public Innovation Laboratory (LIP) promoted by the National Institute of Public Administration (INAP), where pilots have been carried out on the use of technologies to promote the new generation of jobs, intermunicipal collaboration to share talent or the decentralization of selective tests. In addition, they have an Innovation Resources Catalogue where tools with open licences launched by various organisations are compiled and can be used to support public entrepreneurs.

It is also worth highlighting the Spanish Network for Public Innovation and Scientific Transfer, promoted by the NovaGob Foundation. It is a collaborative space that brings together professionals, public administrations, universities and third sector organisations with the aim of transforming public management in Spain. Through working groups and repositories of good practices, it promotes the use of artificial intelligence, administrative simplification and the improvement of citizen service.

We also find public innovation laboratories at the regional level, such as Govtechlab Madrid, a project led by the madri+d Foundation for Knowledge that connects startups and digital SMEs with public institutions to solve real challenges. During the 2023/2024 academic year, they launched 9 pilots, for example, to collect and analyse the opinion of citizens to make better decisions in the Alcobendas City Council, unify the collection and management of data in the registrations of the activities of the Youth Area of the Boadilla del Monte City Council or provide truthful and updated information digitally on the commercial fabric of Mostoles.

The role of governments and public institutions

Innovation in public policy can be driven by a diversity of actors: public administrations open to change, universities and research centres, civic startups and technology companies, civil society organisations or committed citizens.

The European Commission, for example, plays a key role in strengthening the science-for-policy ecosystem in Europe, promoting the effective use of scientific knowledge in decision-making at all levels: European, national, regional and local. Through programmes such as Horizon Europe and the European Research Area Policy Agenda 2025-2027, actions are promoted to develop capacities, share good practices and align research with societal needs.

In Spain we also find actions such as the recent call for funding from the Spanish Foundation for Science and Technology (FECYT), the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, and the National Office of Scientific Advice, whose objective is to promote:

- Research projects that generate new scientific evidence applicable to the design of public policies (Category A).

- Scientific advice and knowledge transfer activities between researchers and public officials (Category B).

Projects can receive up to €100,000 (Category A) or €25,000 (Category B), covering up to 90% of the total cost. Research organizations, universities, health entities, technology centers, R+D centers and other actors that promote the transfer of R+D can participate. The deadline to apply for the aid ends on September 17, 2025. For more information, you should visit the rules of the call or attend some training sessions that are being held.

Conclusion

In a world where social, economic and environmental challenges are increasingly complex, we need new ways of thinking and acting from public institutions. For this reason, R+P is not a fad, it is a necessity that allows us to move from "we think it works" to "we know it works", promoting a more adaptive, agile and effective policy.

Over the last few years we have seen spectacular advances in the use of artificial intelligence (AI) and, behind all these achievements, we will always find the same common ingredient: data. An illustrative example known to everyone is that of the language models used by OpenAI for its famous ChatGPT, such as GPT-3, one of its first models that was trained with more than 45 terabytes of data, conveniently organized and structured to be useful.

Without sufficient availability of quality and properly prepared data, even the most advanced algorithms will not be of much use, neither socially nor economically. In fact, Gartner estimates that more than 40% of emerging AI agent projects today will end up being abandoned in the medium term due to a lack of adequate data and other quality issues. Therefore, the effort invested in standardizing, cleaning, and documenting data can make the difference between a successful AI initiative and a failed experiment. In short, the classic principle of "garbage in, garbage out" in computer engineering applied this time to artificial intelligence: if we feed an AI with low-quality data, its results will be equally poor and unreliable.

Becoming aware of this problem arises the concept of "AI Data Readiness" or preparation of data to be used by artificial intelligence. In this article, we'll explore what it means for data to be "AI-ready", why it's important, and what we'll need for AI algorithms to be able to leverage our data effectively. This results in greater social value, favoring the elimination of biases and the promotion of equity.

What does it mean for data to be "AI-ready"?

Having AI-ready data means that this data meets a series of technical, structural, and quality requirements that optimize its use by artificial intelligence algorithms. This includes multiple aspects such as the completeness of the data, the absence of errors and inconsistencies, the use of appropriate formats, metadata and homogeneous structures, as well as providing the necessary context to be able to verify that they are aligned with the use that AI will give them.

Preparing data for AI often requires a multi-stage process. For example, again the consulting firm Gartner recommends following the following steps:

- Assess data needs according to the use case: identify which data is relevant to the problem we want to solve with AI (the type of data, volume needed, level of detail, etc.), understanding that this assessment can be an iterative process that is refined as the AI project progresses.

- Align business areas and get management support: present data requirements to managers based on identified needs and get their backing, thus securing the resources required to prepare the data properly.

- Develop good data governance practices: implement appropriate data management policies and tools (quality, catalogs, data lineage, security, etc.) and ensure that they also incorporate the needs of AI projects.

- Expand the data ecosystem: integrate new data sources, break down potential barriers and silos that are working in isolation within the organization and adapt the infrastructure to be able to handle the large volumes and variety of data necessary for the proper functioning of AI.

- Ensure scalability and regulatory compliance: ensure that data management can scale as AI projects grow, while maintaining a robust governance framework in line with the necessary ethical protocols and compliance with existing regulations.

If we follow a strategy like this one, we will be able to integrate the new requirements and needs of AI into our usual data governance practices. In essence, it is simply a matter of ensuring that our data is prepared to feed AI models with the minimum possible friction, avoiding possible setbacks later in the day during the development of projects.

Open data "ready for AI"

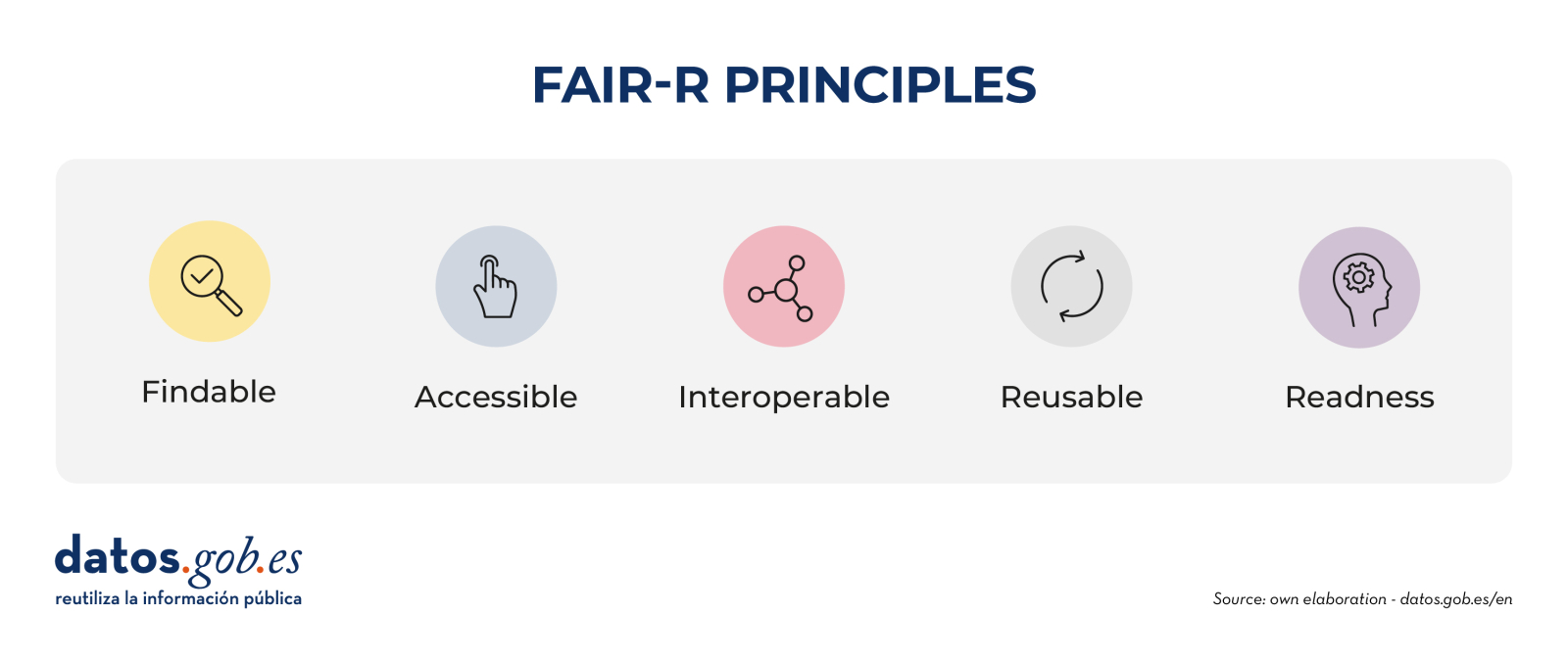

In the field of open science and open data, the FAIR principles have been promoted for years. These acronyms state that data must be locatable, accessible, interoperable and reusable. The FAIR principles have served to guide the management of scientific and open data to make them more useful and improve their use by the scientific community and society at large. However, these principles were not designed to address the new needs associated with the rise of AI.

Therefore, the proposal is currently being made to extend the original principles by adding a fifth readiness principle for AI, thus moving from the initial FAIR to FAIR-R or FAIR². The aim would be precisely to make explicit those additional attributes that make the data ready to accelerate its responsible and transparent use as a necessary tool for AI applications of high public interest

What exactly would this new R add to the FAIR principles? In essence, it emphasizes some aspects such as:

- Labelling, annotation and adequate enrichment of data.

- Transparency on the origin, lineage and processing of data.

- Standards, metadata, schemas and formats optimal for use by AI.

- Sufficient coverage and quality to avoid bias or lack of representativeness.

In the context of open data, this discussion is especially relevant within the discourse of the "fourth wave" of the open data movement, through which it is argued that if governments, universities and other institutions release their data, but it is not in the optimal conditions to be able to feed the algorithms, A unique opportunity for a whole new universe of innovation and social impact would be missing: improvements in medical diagnostics, detection of epidemiological outbreaks, optimization of urban traffic and transport routes, maximization of crop yields or prevention of deforestation are just a few examples of the possible lost opportunities.

And if not, we could also enter a long "data winter", where positive AI applications are constrained by poor-quality, inaccessible, or biased datasets. In that scenario, the promise of AI for the common good would be frozen, unable to evolve due to a lack of adequate raw material, while AI applications led by initiatives with private interests would continue to advance and increase unequal access to the benefit provided by technologies.

Conclusion: the path to quality, inclusive AI with true social value

We can never take for granted the quality or suitability of data for new AI applications: we must continue to evaluate it, work on it and carry out its governance in a rigorous and effective way in the same way as it has been recommended for other applications. Making our data AI-ready is therefore not a trivial task, but the long-term benefits are clear: more accurate algorithms, reduced unwanted bias, increased transparency of AI, and extended its benefits to more areas in an equitable way.

Conversely, ignoring data preparation carries a high risk of failed AI projects, erroneous conclusions, or exclusion of those who do not have access to quality data. Addressing the unfinished business on how to prepare and share data responsibly is essential to unlocking the full potential of AI-driven innovation for the common good. If quality data is the foundation for the promise of more humane and equitable AI, let's make sure we build a strong enough foundation to be able to reach our goal.