As part of the European Cybersecurity Awareness Month, the European data portal, data.europa.eu, has organized a webinar focused on the protection of open data.This event comes at a critical time when organisations, especially in the public sector, face the challenge of balancing data transparency and accessibility with the need to protect against cyber threats.

The online seminar was attended by experts in the field of cybersecurity and data protection, both from the private and public sector.

The expert panel addressed the importance of open data for government transparency and innovation, as well as emerging risks related to data breaches, privacy issues and other cybersecurity threats. Data providers, particularly in the public sector, must manage this paradox of making data accessible while ensuring its protection against malicious use.

During the event, a number of malicious tactics used by some actors to compromise the security of open data were identified. These tactics can occur both before and after publication. Knowing about them is the first step in preventing and counteracting them.

Pre-publication threats

Before data is made publicly available, it may be subject to the following threats:

-

Supply chain attacks: attackers can sneak malicious code into open data projects, such as commonly used libraries (Pandas, Numpy or visualisation modules), by exploiting the trust placed in these resources. This technique allows attackers to compromise larger systems and collect sensitive information in a gradual and difficult to detect manner.

- Manipulation of information: data may be deliberately altered to present a false or misleading picture. This may include altering numerical values, distorting trends or creating false narratives. These actions undermine the credibility of open data sources and can have significant consequences, especially in contexts where data is used to make important decisions.

- Envenenamiento de datos (data poisoning): attackers can inject misleading or incorrect data into datasets, especially those used for training AI models. This can result in models that produce inaccurate or biased results, leading to operational failures or poor business decisions.

Post-publication threats

Once data has been published, it remains vulnerable to a variety of attacks:

-

Compromise data integrity: attackers can modify published data, altering files, databases or even data transmission. These actions can lead to erroneous conclusions and decisions based on false information.

- Re-identification and breach of privacy: data sets, even if anonymised, can be combined with other sources of information to reveal the identity of individuals. This practice, known as 're-identification', allows attackers to reconstruct detailed profiles of individuals from seemingly anonymous data. This represents a serious violation of privacy and may expose individuals to risks such as fraud or discrimination.

- Sensitive data leakage: open data initiatives may accidentally expose sensitive information such as medical records, personally identifiable information (emails, names, locations) or employment data. This information can be sold on illicit markets such as the dark web, or used to commit identity fraud or discrimination.

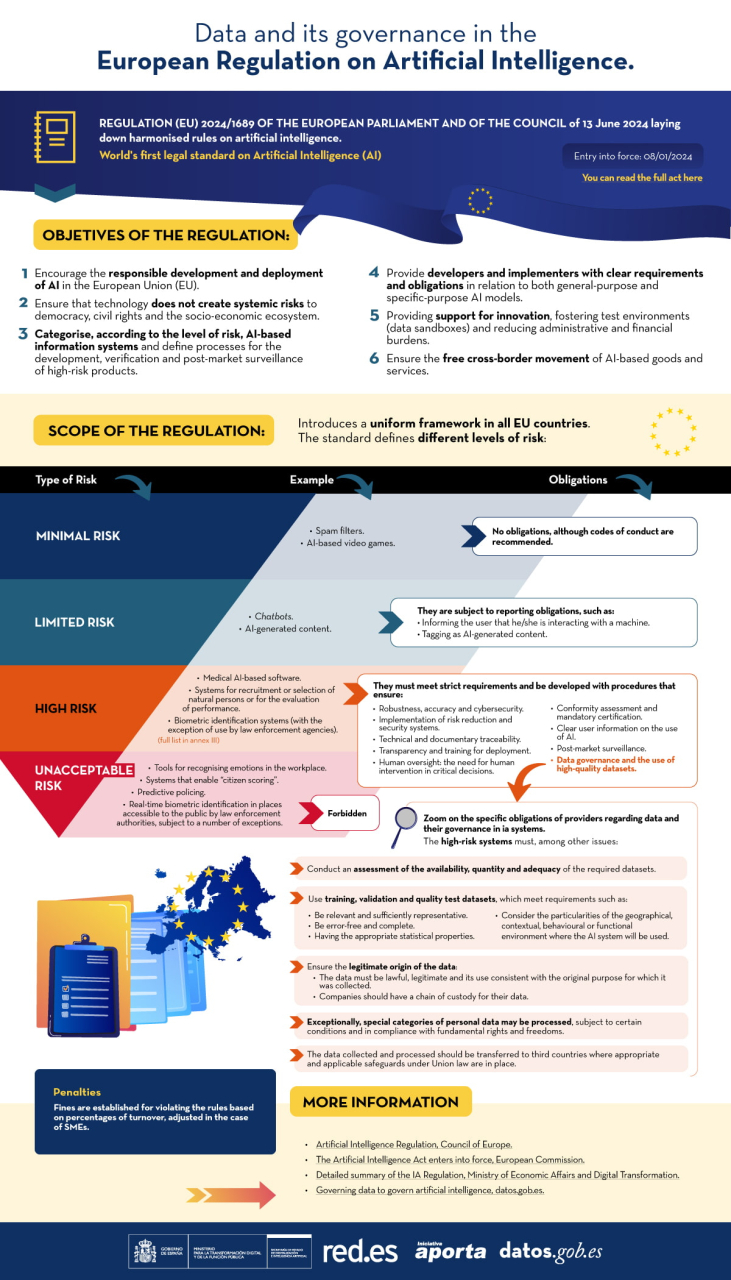

Following on from these threats, the webinar presented a case study on how cyber disinformation exploited open data during the energy and political crisis associated with the Ukraine war in 2022. Attackers manipulated data, generated false content with artificial intelligence and amplified misinformation on social media to create confusion and destabilise markets.

Figure 1. Slide from the webinar presentation "Safeguarding open data: cybersecurity essentials and skills for data providers".

Data protection and data governance strategies

In this context, the implementation of a robust governance structure emerges as a fundamental element for the protection of open data. This framework should incorporate rigorous quality management to ensure accuracy and consistency of data, together with effective updating and correction procedures. Security controls should be comprehensive, including:

- Technical protection measures.

- Integrity check procedures.

- Access and modification monitoring systems.

Risk assessment and risk management requires a systematic approach starting with a thorough identification of sensitive and critical data. This involves not only the cataloguing of critical information, but also a detailed assessment of its sensitivity and strategic value. A crucial aspect is the identification and exclusion of personal data that could allow the identification of individuals, implementing robust anonymisation techniques where necessary.

For effective protection, organisations must conduct comprehensive risk analyses to identify potential vulnerabilities in their data management systems and processes. These analyses should lead to the implementation of robust security controls tailored to the specific needs of each dataset. In this regard, the implementation of data sharing agreements establishes clear and specific terms for the exchange of information with other organisations, ensuring that all parties understand their data protection responsibilities.

Experts stressed that data governance must be structured through well-defined policies and procedures that ensure effective and secure information management. This includes the establishment of clear roles and responsibilities, transparent decision-making processes and monitoring and control mechanisms. Mitigation procedures must be equally robust, including well-defined response protocols, effective preventive measures and continuous updating of protection strategies.

In addition, it is essential to maintain a proactive approach to security management. A strategy that anticipates potential threats and adapts protection measures as the risk landscape evolves. Ongoing staff training and regular updating of policies and procedures are key elements in maintaining the effectiveness of these protection strategies. All this must be done while maintaining a balance between the need for protection and the fundamental purpose of open data: its accessibility and usefulness to the public.

Legal aspects and compliance

In addition, the webinar explained the legal and regulatory framework surrounding open data. A crucial point was the distinction between anonymization and pseudo-anonymization in the context of the GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation).

On the one hand, anonymised data are not considered personal data under the GDPR, because it is impossible to identify individuals. However, pseudo-anonymisation retains the possibility of re-identification if combined with additional information. This distinction is crucial for organisations handling open data, as it determines which data can be freely published and which require additional protections.

To illustrate the risks of inadequate anonymisation, the webinar presented the Netflix case in 2006, when the company published a supposedly anonymised dataset to improve its recommendation algorithm. However, researchers were able to "re-identify" specific users by combining this data with publicly available information on IMDb. This case demonstrates how the combination of different datasets can compromise privacy even when anonymisation measures have been taken.

In general terms, the role of the Data Governance Act in providing a horizontal governance framework for data spaces was highlighted, establishing the need to share information in a controlled manner and in accordance with applicable policies and laws. The Data Governance Regulation is particularly relevant to ensure that data protection, cybersecurity and intellectual property rights are respected in the context of open data.

The role of AI and cybersecurity in data security

The conclusions of the webinar focused on several key issues for the future of open data. A key element was the discussion on the role of artificial intelligence and its impact on data security. It highlighted how AI can act as a cyber threat multiplier, facilitating the creation of misinformation and the misuse of open data.

On the other hand, the importance of implementing Privacy Enhancing Technologies (PETs ) as fundamental tools to protect data was emphasized. These include anonymisation and pseudo-anonymisation techniques, data masking, privacy-preserving computing and various encryption mechanisms. However, it was stressed that it is not enough to implement these technologies in isolation, but that they require a comprehensive engineering approach that considers their correct implementation, configuration and maintenance.

The importance of training

The webinar also emphasised the critical importance of developing specific cybersecurity skills. ENISA's cyber skills framework, presented during the session, identifies twelve key professional profiles, including the Cybersecurity Policy and Legal Compliance Officer, the Cybersecurity Implementer and the Cybersecurity Risk Manager. These profiles are essential to address today's challenges in open data protection.

Figure 2. Slide presentation of the webinar " Safeguarding open data: cybersecurity essentials and skills for data providers".

In summary, a key recommendation that emerged from the webinar was the need for organisations to take a more proactive approach to open data management. This includes the implementation of regular impact assessments, the development of specific technical competencies and the continuous updating of security protocols. The importance of maintaining transparency and public confidence while implementing these security measures was also emphasised.

Today, digital technologies are revolutionising various sectors, including the construction sector, driven by the European Digital Strategy which not only promotes innovation and the adoption of digital technologies, but also the use and generation of potentially open data. The incorporation of advanced technologies has fostered a significant transformation in construction project management, making information more accessible and transparent to all stakeholders.

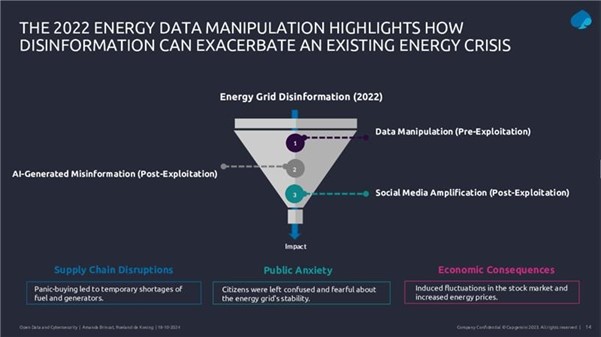

One of the key elements in this transformation are Digital Building Permits and Digital Building Logs, concepts that are improving the efficiency of administrative processes and the execution of construction projects, and which can have a significant impact on the generation and management of data in the municipalities that adopt them.

Digital Building Permits (DBP) and Digital Building Logs (DBL) not only generate key information on infrastructure planning, execution and maintenance, but also make this data accessible to the public and other stakeholders. The availability of this open data enables advanced analysis, academic research, and the development of innovative solutions for building more sustainable and safer infrastructure.

What is the Digital Building Permit?

The Digital Building Permit is the digitalisation of traditional building permit processes. Traditionally, this process was manual, involving extensive exchange of physical documents and coordination between multiple stakeholders. With digitisation, this procedure is simplified and made more efficient, allowing for a faster, more transparent and less error-prone review. Furthermore, thanks to this digitisation, large amounts of valuable data are proactively generated that not only optimise the process, but can also be used to improve transparency and carry out research in the sector. This data can be harnessed for advanced analytics, contributing to the development of smarter and more sustainable infrastructures. It also facilitates the integration of technologies such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) and digital twins, which are essential for the development of smart infrastructures.

- BIM allows the creation of detailed digital representations of infrastructure, incorporating precise information about each building component. This digital model facilitates not only the design, but also the management and maintenance of the building throughout its life cycle. In Spain, the legislation related to the use of Building Information Modeling (BIM) is mainly governed by the Law 9/2017 on Public Sector Contracts. This law establishes the possibility to require the use of BIM in public works projects. This regulation aims to improve efficiency, transparency and sustainability in the procurement and execution of public works and services in Spain.

- Digital twins are virtual replicas of physical infrastructures that allow the behaviour of a building to be simulated and analysed in real time thanks to the data generated. This data is not only crucial for the functioning of the digital twin, but can also be used as open data for research, public policy improvement and transparency in the management of infrastructures. These digital twins are essential to anticipate problems before they occur, optimise energy efficiency and proactively manage maintenance.

Together, these technologies can not only streamline the permitting process, but also ensure that buildings are safer, more sustainable and aligned with current regulations, promoting the development of smart infrastructure in an increasingly digitised environment.

What is a Digital Building Log?

The Digital Building Log is a tool for keeping a detailed and digitised record of all activities, decisions and modifications made during the life of a construction project. This register includes data on permits issued, inspections carried out, design changes, and any other relevant interventions. It functions as a digital logbook that provides a transparent and traceable overview of the entire construction process.

This approach not only improves transparency and traceability, but also facilitates monitoring and compliance by keeping an up-to-date register accessible to all stakeholders.

Figure 1. What are Digital Building Permits and Digital Building Logs? Own elaboration.

Key Projects and Objectives in the Sector

Several European projects are incorporating Digital Building Permits and Digital Building Logs as part of their strategy to modernise the construction sector. Some of the most innovative projects in this field are highlighted below:

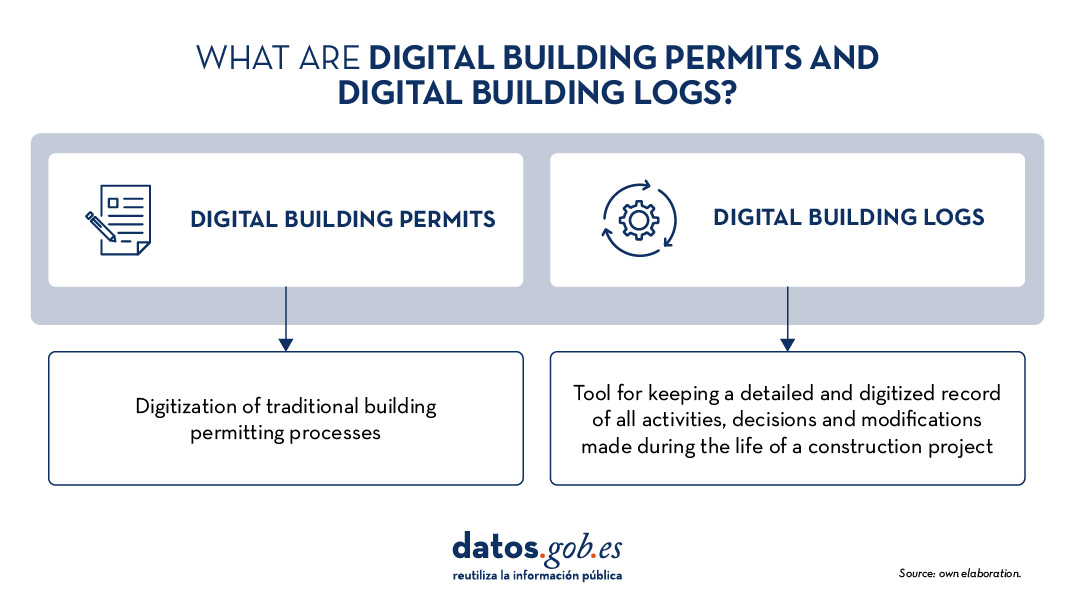

ACCORD

The ACCORD Project (2022-2025) is an European initiative that aims to transform the process of obtaining and managing construction permits through digitisation. ACCORD, which stands for"Automated Compliance Checking and Orchestration of Building Projects", aims to develop a semantic framework to automatically check compliance, improve efficiency and ensure transparency in the building sector. In addition, ACCORD will develop:

- A rule formalisation tool based on semantic web technologies.

- A semantic rules database.

- Microservices for compliance verification in construction.

- A set of open and standardised APIs to enable integrated data flow between building permit, compliance and other information services.

Figure 2. ACCORD project process.Source: Proyecto ACCORD.

The ACCORD Project focuses on several demonstrations in various European countries, each with a specific focus facilitated by the analysis and use of the data:

- In Estonia and Finland, ACCORD focuses on improving accessibility and safety in urban spaces through the automation of building permits. In Estonia, work is being done on automatic verification of compliance with planning and zoning regulations, while in Finland, the focus is on developing healthy and safe urban spaces by digitising the permitting process and integrating urban data.

- In Germany, ACCORD focuses on automated verification for land use permits and green building certification. The project aims to automate the verification of regulatory compliance in these areas by integrating micro-services that automatically verify whether construction projects comply with sustainability and land use regulations before permits are issued.

- In the UK, ACCORD focuses on ensuring the design integrity of structural components of steel modular homes by using BIM modelling and finite element analysis (FEA). This approach allows automatic verification of the compliance of structural components with safety and design standards prior to their implementation in construction. The project facilitates the early detection of potential structural failures, thus improving safety and efficiency in the construction process.

- In Spain, ACCORD focuses on automating urban planning compliance in Malgrat de Martown council using BIM and open cadastral data. The aim is to improve efficiency in the design and construction phase, ensuring that projects comply with local regulations before they start. This includes automatic verification of urban regulations to facilitate faster and more accurate building permits.

CHEK

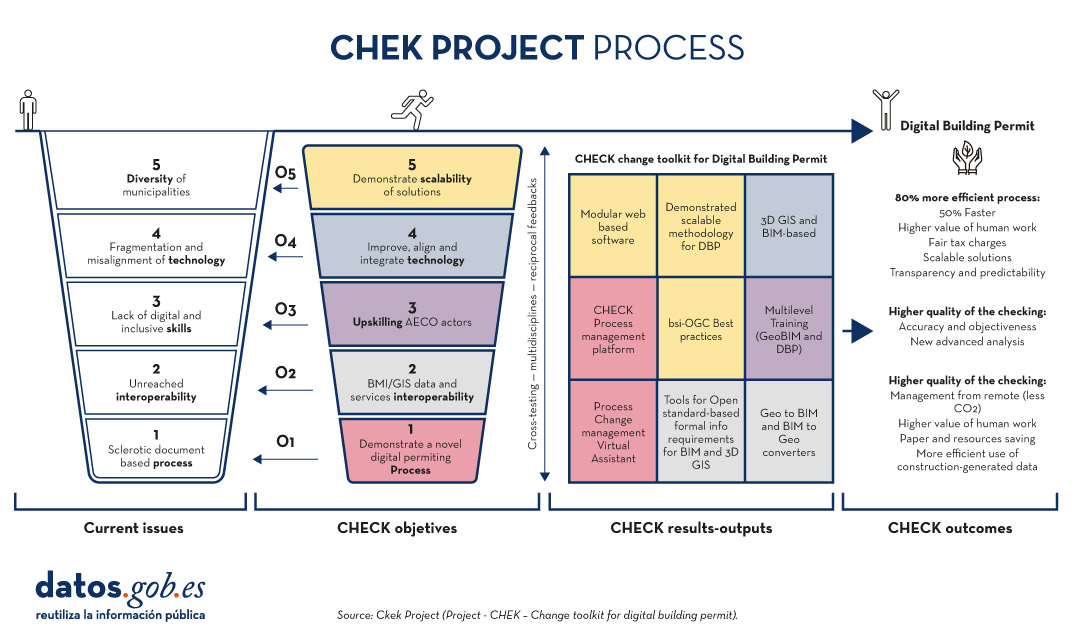

The CHEK Project (2022-2025) which stands for"Change Toolkit for Digital Building Permit" is a European initiative that aims to remove the barriers municipalities face in adopting the digitisation of building permit management processes.

CHEK will develop scalable solutions including open standards and interoperability (geospatial and BIM), educational tools to bridge knowledge gaps and new technologies for permit digitisation and automatic compliance verification. The objective is to align digital technologies with municipal-level administrative processing, improve accuracy and efficiency, and demonstrate scalability in European urban areas, achieving a tRL 7E technology maturity level.

Figure 3. CHEK Project Process. Source: Proyecto CHEK.

This requires:

- Adapt available digital technologies to municipal processes, enabling new methods and business models.

- Develop open data standards, including building information modelling (BIM), 3D urban modelling and reciprocal integration (GeoBIM).

- Improve training for public employees and users.

- Improving, adapting and integrating technology.

- Realise and demonstrate scalability.

CHEK will provide a set of methodological and technological tools to fully digitise building permits and partially automate building design compliance checks, leading to a 60% efficiency improvement and the adoption of DBP by 85% of European municipalities.

The future of construction and the contribution to open data

The implementation of Digital Building Permits and Digital Building Logs is transforming the building landscape. As these tools are integrated into construction processes, future scenarios on the horizon include:

- Digitised construction: In the not too distant future, construction projects could be managed entirely digitally, from permit applications to ongoing project monitoring. This will eliminate the need for physical documents and significantly reduce errors and delays.

- Real-time digital cufflinks: Digital Building Logs will feed digital twins in real time, enabling continuous and predictive monitoring of projects. This will allow developers and regulators to anticipate problems before they occur and make informed decisions quickly.

- Global data interoperability: With the advancement of data spaces, building systems are expected to become globally interoperable. This will facilitate international collaboration and allow standards and best practices to be widely shared and adopted.

Digital Building Permits and Digital Building Logs are not only tools for process optimisation in the building sector, but also vehicles for the creation of open data that can be used by a wide range of actors. The implementation of these systems not only generates technical data on the progress of works, but also provides data that can be reused by authorities, developers and citizens, thus fostering an open collaborative environment. This data can be used to improve urban analysis, assist in public infrastructure planning and optimise monitoring and transparency in project implementation.

The use of open data through these platforms also facilitates the development of innovative applications and technological services that improve efficiency, promote sustainability and contribute to more efficient resource management in cities. Such open data can, for example, allow citizens to access information on building conditions in their area, while giving governments a clearer, real-time view of how projects are developing, enabling data-driven decision-making.

Projects such as ACCORD and CHECK demonstrate how these technologies can integrate digitalisation, automation and open data to transform the European construction sector.

Content prepared by Mayte Toscano, Senior Consultant in Data Economy Technologies. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

In an increasingly information-driven world, open data is transforming the way we understand and shape our societies. This data are a valuable source of knowledge that also helps to drive research, promote technological advances and improve policy decision-making.

In this context, the Publications Office of the European Union organises the annual EU Open Data Days to highlight the role of open data in European society and all the new developments. The next edition will take place on 19-20 March 2025 at the European Conference Centre Luxembourg (ECCL) and online.

This event, organised by the data.europa.eu, europe's open data portal, will bring together data providers, enthusiasts and users from all over the world, and will be a unique opportunity to explore the potential of open data in various sectors. From success stories to new initiatives, this event is a must for anyone interested in the future of open data.

What are EU Open Data Days?

EU Open Data Days are an opportunity to exchange ideas and network with others interested in the world of open data and related technologies. This event is particularly aimed at professionals involved in data publishing and reuse, analysis, policy making or academic research.However, it is also open to the general public. After all, these are two days of sharing, learning and contributing to the future of open data in Europe.

What can you expect from EU Open Data Days 2025?

The event programme is designed to cover a wide range of topics that are key to the open data ecosystem, such as:

- Success stories and best practices: real experiences from those at the forefront of data policy in Europe, to learn how open data is being used in different business models and to address the emerging frontiers of artificial intelligence.

- Challenges and solutions: an overview of the challenges of using open data, from the perspective of publishers and users, addressing technical, ethical and legal issues.

- Visualising impact: analysis of how data visualisation is changing the way we communicate complex information and how it can facilitate better decision-making and encourage citizen participation.

- Data literacy: training to acquire new skills to maximise the potential of open data in each area of work or interest of the attendees.

An event open to all sectors

The EU Open Data Days are aimed at a wide audience: the public, the media, the general public and the general public.

- Private sector: data analytics specialists, developers and technology solution providers will be able to learn new techniques and trends, and connect with other professionals in the sector.

- Public sector: policy makers and government officials will discover how open data can be used to improve decision-making, increase transparency and foster innovation in policy design.

- Academia and education: researchers, teachers and students will be able to engage in discussions on how open data is fuelling new research and advances in areas as diverse as social sciences, emerging technologies and economics.

- Journalism and media: Data journalists and communicators will learn how to use data visualisation to tell more powerful and accurate stories, fostering better public understanding of complex issues.

Submit your proposal before 22 October

Would you like to present a paper at the EU Open Data Days 2025? You have until Tuesday 22 October to send your proposal on one of the above-mentioned themes. Papers that address open data or related areas are sought, such as data visualisation or the use of artificial intelligence in conjunction with open data.

The European data portal is looking for inspiring cases that demonstrate the impact of open data use in Europe and beyond. The call is open to participants from all over the world and from all sectors: from international, national and EU public organisations, to academics, journalists and data visualisation experts. Selected projects will be part of the conference programme, and presentations must be made in English.

Proposals should be between 20 and 35 minutes in length, including time for questions and answers. If your proposal is selected, travel and accommodation expenses (one night) will be reimbursed for participants from the academic sector, the public sector and NGOs.

For further details and clarifications, please contact the organising team by email: EU-Open-Data-Days@ec.europa.eu.

- Deadline for submission of proposals: 22 October 2024.

- Notification to selected participants: November 2024.

- Delivery of the draft presentation: 15 January 2025.

- Delivery of the final presentation: 18 February 2025.

- Conference dates: 19-20 March 2025.

The future of open data is now. The EU Open Data Days 2025 will not only be an opportunity to learn about the latest trends and practices in data use, but also to build a stronger and more collaborative community around open data. Registration for the event will open in late autumn 2024, we will announce it through our social media channels on TwitterlinkedIn and Instagram.

Data literacy has become a crucial issue in the digital age. This concept refers to the ability of people to understand how data is used, how it is accessed, created, analysed, used or reused, and communicated.

We live in a world where data and algorithms influence everyday decisions and the opportunities people have to live well. Its effect can be felt in areas ranging from advertising and employment provision to criminal justice and social welfare. It is therefore essential to understand how data is generated and used.

Data literacy can involve many areas, but we will focus on its relationship with digital rights on the one hand and Artificial Intelligence (AI) on the other. This article proposes to explore the importance of data literacy for citizenship, addressing its implications for the protection of individual and collective rights and the promotion of a more informed and critical society in a technological context where artificial intelligence is becoming increasingly important.

The context of digital rights

More and more studies studies increasingly indicate that effective participation in today's data-driven, algorithm-driven society requires data literacy indicating that effective participation in today's data-driven, algorithm-driven society requires data literacy. Civil rights are increasingly translating into digital rights as our society becomes more dependent on digital technologies and environments digital rights as our society becomes more dependent on digital technologies and environments. This transformation manifests itself in various ways:

- On the one hand, rights recognised in constitutions and human rights declarations are being explicitly adapted to the digital context. For example, freedom of expression now includes freedom of expression online, and the right to privacy extends to the protection of personal data in digital environments. Moreover, some traditional civil rights are being reinterpreted in the digital context. One example of this is the right to equality and non-discrimination, which now includes protection against algorithmic discrimination and against bias in artificial intelligence systems. Another example is the right to education, which now also extends to the right to digital education. The importance of digital skills in society is recognised in several legal frameworks and documents, both at national and international level, such as the Organic Law 3/2018 on Personal Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights (LOPDGDD) in Spain. Finally, the right of access to the internet is increasingly seen as a fundamental right, similar to access to other basic services.

- On the other hand, rights are emerging that address challenges unique to the digital world, such as the right to be forgotten (in force in the European Union and some other countries that have adopted similar legislation1), which allows individuals to request the removal of personal information available online, under certain conditions. Another example is the right to digital disconnection (in force in several countries, mainly in Europe2), which ensures that workers can disconnect from work devices and communications outside working hours. Similarly, there is a right to net neutrality to ensure equal access to online content without discrimination by service providers, a right that is also established in several countries and regions, although its implementation and scope may vary. The EU has regulations that protect net neutrality, including Regulation 2015/2120, which establishes rules to safeguard open internet access. The Spanish Data Protection Act provides for the obligation of Internet providers to provide a transparent offer of services without discrimination on technical or economic grounds. Furthermore, the right of access to the internet - related to net neutrality - is recognised as a human right by the United Nations (UN).

This transformation of rights reflects the growing importance of digital technologies in all aspects of our lives.

The context of artificial intelligence

The relationship between AI development and data is fundamental and symbiotic, as data serves as the basis for AI development in a number of ways:

- Data is used to train AI algorithms, enabling them to learn, detect patterns, make predictions and improve their performance over time.

- The quality and quantity of data directly affect the accuracy and reliability of AI systems. In general, more diverse and complete datasets lead to better performing AI models.

- The availability of data in various domains can enable the development of AI systems for different use cases.

Data literacy has therefore become increasingly crucial in the AI era, as it forms the basis for effectively harnessing and understanding AI technologies.

In addition, the rise of big data and algorithms has transformed the mechanisms of participation, presenting both challenges and opportunities. Algorithms, while they may be designed to be fair, often reflect the biases of their creators or the data they are trained on. This can lead to decisions that negatively affect vulnerable groups.

In this regard, legislative and academic efforts are being made to prevent this from happening. For example, the EuropeanArtificial Intelligence Act (AI Act) includes safeguards to avoid harmful biases in algorithmic decision-making. For example, it classifies AI systems according to their level of potential risk and imposes stricter requirements on high-risk systems. In addition, it requires the use of high quality data to train the algorithms, minimising bias, and provides for detailed documentation of the development and operation of the systems, allowing for audits and evaluations with human oversight. It also strengthens the rights of persons affected by AI decisions, including the right to challenge decisions made and their explainability, allowing affected persons to understand how a decision was reached.

The importance of digital literacy in both contexts

Data literacy helps citizens make informed decisions and understand the full implications of their digital rights, which are also considered, in many respects, as mentioned above, to be universal civil rights. In this context, data literacy serves as a critical filter for full civic participation that enables citizens to influence political and social decisions full civic participation that enables citizens to influence political and social decisions. That is,those who have access to data and the skills and tools to navigate the data infrastructure effectively can intervene and influencepolitical and social processes in a meaningful way , something which promotes the Open Government Partnership.

On the other hand, data literacy enables citizens to question and understand these processes, fostering a culture of accountability and transparency in the use of AI. There arealso barriers to participation in data-driven environments. One of these barriers is the digital divide (i.e. deprivation of access to infrastructure, connectivity and training, among others) and, indeed, lack of data literacy. The latter is therefore a crucial concept for overcoming the challenges posed by datification datification of human relations and the platformisation of content and services.

Recommendations for implementing a preparedness partnership

Part of the solution to addressing the challenges posed by the development of digital technology is to include data literacy in educational curricula from an early age.

This should cover:

- Data basics: understanding what data is, how it is collected and used.

- Critical analysis: acquisition of the skills to evaluate the quality and source of data and to identify biases in the information presented. It seeks to recognise the potential biases that data may contain and that may occur in the processing of such data, and to build capacity to act in favour of open data and its use for the common good.

- Rights and regulations: information on data protection rights and how European laws affect the use of AI. This area would cover all current and future regulation affecting the use of data and its implication for technology such as AI.

- Practical applications: the possibility of creating, using and reusing open data available on portals provided by governments and public administrations, thus generating projects and opportunities that allow people to work with real data, promoting active, contextualised and continuous learning.

By educating about the use and interpretation of data, it fosters a more critical society that is able to demand accountability in the use of AI. New data protection laws in Europe provide a framework that, together with education, can help mitigate the risks associated with algorithmic abuse and promote ethical use of technology. In a data-driven society, where data plays a central role, there is a need to foster data literacy in citizens from an early age.

1The right to be forgotten was first established in May 2014 following a ruling by the Court of Justice of the European Union. Subsequently, in 2018, it was reinforced with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)which explicitly includes it in its Article 17 as a "right of erasure". In July 2015, Russia passed a law allowing citizens to request the removal of links on Russian search engines if the information"violates Russian law or if it is false or outdated". Turkey has established its own version of the right to be forgotten, following a similar model to that of the EU. Serbia has also implemented a version of the right to be forgotten in its legislation. In Spain, the Ley Orgánica de Protección de Datos Personales (LOPD) regulates the right to be forgotten, especially with regard to debt collection files. In the United Statesthe right to be forgotten is considered incompatible with the Constitution, mainly because of the strong protection of freedom of expression. However, there are some related regulations, such as the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970, which allows in certain situations the deletion of old or outdated information in credit reports.

2Some countries where this right has been established include Spain, regulated by Article 88 of Organic Law 3/2018 on Personal Data Protection; France, which, in 2017, became the first country to pass a law on the right to digital disconnection; Germany, included in the Working Hours and Rest Time Act(Arbeitszeitgesetz); Italy, under Law 81/201; and Belgium. Outside Europe, it is, for example, in Chile.

Content prepared by Miren Gutiérrez, PhD and researcher at the University of Deusto, expert in data activism, data justice, data literacy and gender disinformation. The contents and views reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author.

Digital transformation has become a fundamental pillar for the economic and social development of countries in the 21st century. In Spain, this process has become particularly relevant in recent years, driven by the need to adapt to an increasingly digitalised and competitive global environment. The COVID-19 pandemic acted as a catalyst, accelerating the adoption of digital technologies in all sectors of the economy and society.

However, digital transformation involves not only the incorporation of new technologies, but also a profound change in the way organisations operate and relate to their customers, employees and partners. In this context, Spain has made significant progress, positioning itself as one of the leading countries in Europe in several aspects of digitisation.

The following are some of the most prominent reports analysing this phenomenon and its implications.

State of the Digital Decade 2024 report

The State of the Digital Decade 2024 report examines the evolution of European policies aimed at achieving the agreed objectives and targets for successful digital transformation. It assesses the degree of compliance on the basis of various indicators, which fall into four groups: digital infrastructure, digital business transformation, digital skills and digital public services.

Figure 1. Taking stock of progress towards the Digital Decade goals set for 2030, “State of the Digital Decade 2024 Report”, European Commission.

In recent years, the European Union (EU) has significantly improved its performance by adopting regulatory measures - with 23 new legislative developments, including, among others, the Data Governance Regulation and the Data Regulation- to provide itself with a comprehensive governance framework: the Digital Decade Policy Agenda 2030.

The document includes an assessment of the strategic roadmaps of the various EU countries. In the case of Spain, two main strengths stand out:

- Progress in the use of artificial intelligence by companies (9.2% compared to 8.0% in Europe), where Spain's annual growth rate (9.3%) is four times higher than the EU (2.6%).

- The large number of citizens with basic digital skills (66.2%), compared to the European average (55.6%).

On the other hand, the main challenges to overcome are the adoption of cloud services ( 27.2% versus 38.9% in the EU) and the number of ICT specialists ( 4.4% versus 4.8% in Europe).

The following image shows the forecast evolution in Spain of the key indicators analysed for 2024, compared to the targets set by the EU for 2030.

Figure 2. Key performance indicators for Spain, “Report on the State of the Digital Decade 2024”, European Commission.

Spain is expected to reach 100% on virtually all indicators by 2030. 26.7 billion (1.8 % of GDP), without taking into account private investments. This roadmap demonstrates the commitment to achieving the goals and targets of the Digital Decade.

In addition to investment, to achieve the objective, the report recommends focusing efforts in three areas: the adoption of advanced technologies (AI, data analytics, cloud) by SMEs; the digitisation and promotion of the use of public services; and the attraction and retention of ICT specialists through the design of incentive schemes.

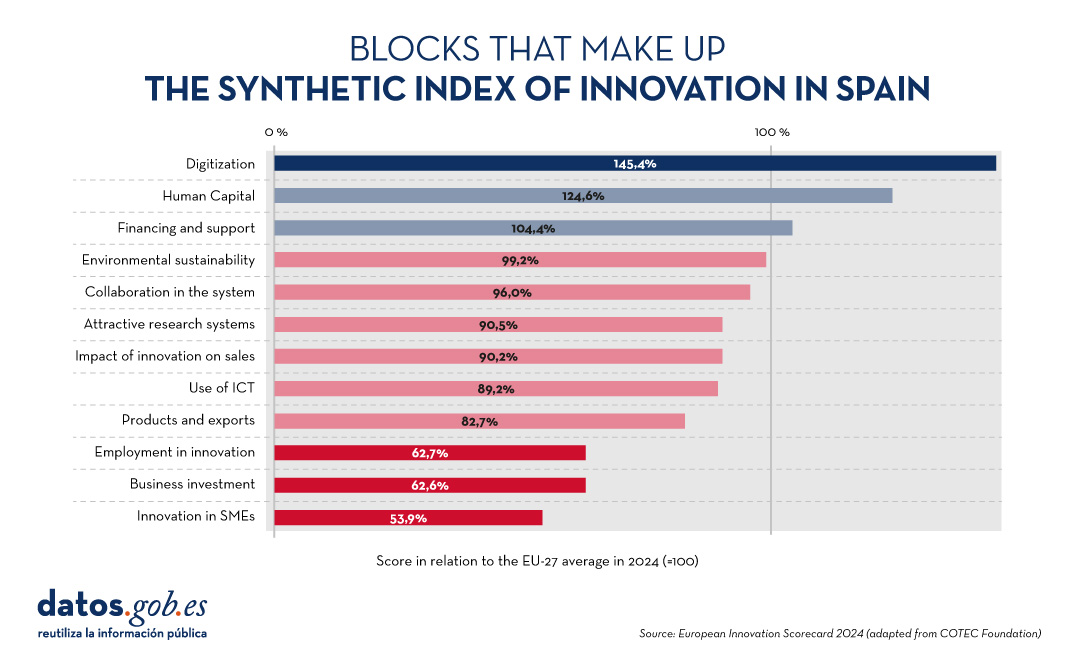

European Innovation Scoreboard 2024

The European Innovation Scoreboard carries out an annual benchmarking of research and innovation developments in a number of countries, not only in Europe. The report classifies regions into four innovation groups, ranging from the most innovative to the least innovative: Innovation Leaders, Strong Innovators, Moderate Innovators and Emerging Innovators.

Spain is leading the group of moderate innovators, with a performance of 89.9% of the EU average. This represents an improvement compared to previous years and exceeds the average of other countries in the same category, which is 84.8%. Our country is above the EU average in three indicators: digitisation, human capital and financing and support. On the other hand, the areas in which it needs to improve the most are employment in innovation, business investment and innovation in SMEs. All this is shown in the following graph:

Figure 3. Blocks that make up the synthetic index of innovation in Spain, European Innovation Scorecard 2024 (adapted from the COTEC Foundation).

Spain's Digital Society Report 2023

The Telefónica Foundation also periodically publishes a report which analyses the main changes and trends that our country is experiencing as a result of the technological revolution.

The edition currently available is the 2023 edition. It highlights that "Spain continues to deepen its digital transformation process at a good pace and occupies a prominent position in this aspect among European countries", highlighting above all the area of connectivity. However, digital divides remain, mainly due to age.

Progress is also being made in the relationship between citizens and digital administrations: 79.7% of people aged 16-74 used websites or mobile applications of an administration in 2022. On the other hand, the Spanish business fabric is advancing in its digitalisation, incorporating digital tools, especially in the field of marketing. However, there is still room for improvement in aspects of big data analysis and the application of artificial intelligence, activities that are currently implemented, in general, only by large companies.

Artificial Intelligence and Data Talent Report

IndesIA, an association that promotes the use of artificial intelligence and Big Data in Spain, has carried out a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the data and artificial intelligence talent market in 2024 in our country.

According to the report, the data and artificial intelligence talent market represents almost 19% of the total number of ICT professionals in our country. In total, there are 145,000 professionals (+2.8% from 2023), of which only 32% are women. Even so, there is a gap between supply and demand, especially for natural language processing engineers. To address this situation, the report analyses six areas for improvement: workforce strategy and planning, talent identification, talent activation, engagement, training and development, and data-driven culture .

Other reports of interest

The COTEC Foundation also regularly produces various reports on the subject. On its website we can find documents on the budget execution of R&D in the public sector, the social perception of innovation or the regional talent map.

For their part, the Orange Foundation in Spain and the consultancy firm Nae have produced a report to analyse digital evolution over the last 25 years, the same period that the Foundation has been operating in Spain. The report highlights that, between 2013 and 2018, the digital sector has contributed around €7.5 billion annually to the country's GDP.

In short, all of them highlight Spain's position among the European leaders in terms of digital transformation, but with the need to make progress in innovation. This requires not only boosting economic investment, but also promoting a cultural change that fosters creativity. A more open and collaborative mindset will allow companies, administrations and society in general to adapt quickly to technological changes and take advantage of the opportunities they bring to ensure a prosperous future for Spain.

Do you know of any other reports on the subject? Leave us a comment or write to us at dinamizacion@datos.gos.es.

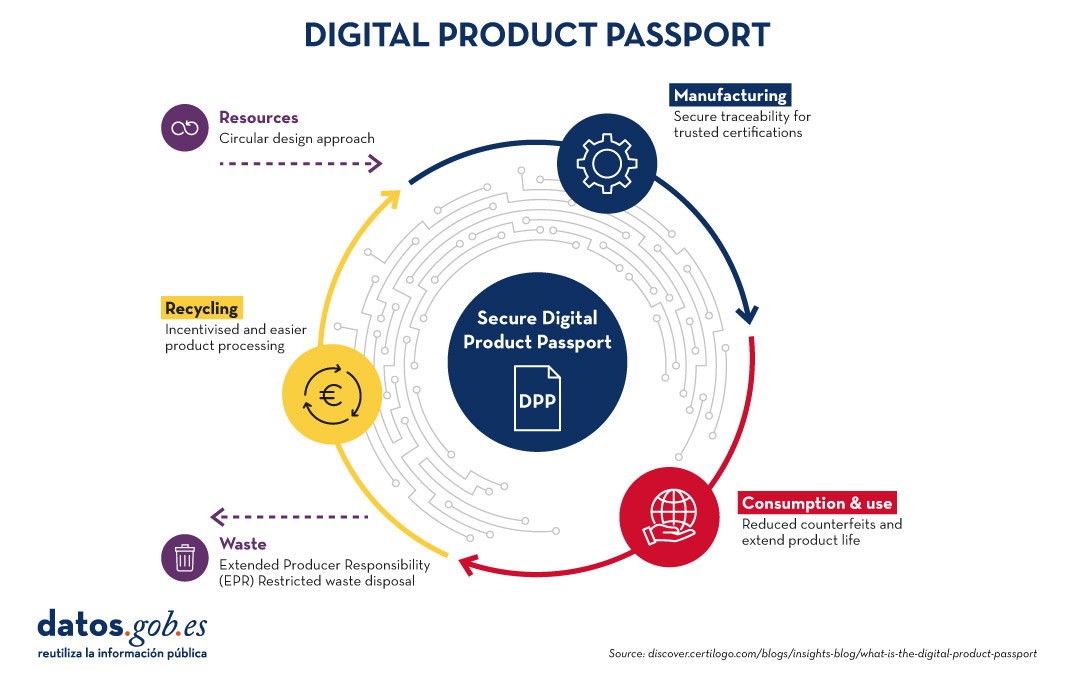

Digital transformation has reached almost every aspect and sector of our lives, and the world of products and services is no exception. In this context, the Digital Product Passport (DPP) concept is emerging as a revolutionary tool to foster sustainability and the circular economy. Accompanied by initiatives such as CIRPASS (Circular Product Information System for Sustainability), the DPP promises to change the way we interact with products throughout their life cycle. In this article, we will explore what DPP is, its origins, applications, risks and how it can affect our daily lives and the protection of our personal data.

What is the Digital Product Passport (DPP)? Origin and importance

The Digital Product Passport is a digital collection of key information about a product, from manufacturing to recycling. This passport allows products to be tracked and managed more efficiently, improving transparency and facilitating sustainable practices. The information contained in a DPP may include details on the materials used, the manufacturing process, the supply chain, instructions for use and how to recycle the product at the end of its life.

The DPP has been developed in response to the growing need to promote the circular economy and reduce the environmental impact of products. The European Union (EU) has been a pioneer in promoting policies and regulations that support sustainability. Initiatives such as the EU's Circular Economy Action Plan have been instrumental in driving the DPP forward. The objectives of this plan are as follows:

- Greater Transparency: Consumers no longer have to guess about the origin of their products and how to dispose of them correctly. With a machine-readable DPP (e.g. QR code or NFC tag) attached to end products, consumers can make informed purchasing decisions and brands can eliminate greenwashing with confidence.

- Simplified Compliance: By creating an audit of events and transactions in a product's value chain, the DPP provides the brand and its suppliers with the necessary data to address compliance demands efficiently.

- Sustainable Production: By tracking and reporting the social and environmental impacts of a product from source to disposal, brands can make data-driven decisions to optimise sustainability in product development.

- Circular Economy: The DPP facilitates a circular economy by promoting eco-design and the responsible production of durable products that can be reused, remanufactured and disposed of correctly.

The following image summarises the main advantages of the digital passport at each stage of the digital product manufacturing process:

CIRPASS as a facilitator of DPP implementation

CIRPASS is a platform that supports the implementation of the DPP. This European initiative aims to standardise the collection and exchange of data on products, facilitating their traceability and management throughout their life cycle. CIRPASS plays a crucial role in creating an interoperable digital framework that connects manufacturers, consumers and recyclers.

DPP applications in various sectors

On 5 March 2024, CIRPASS, in collaboration with the European Commission, organised an event on the future development of the Digital Product Passport. The event brought together various stakeholders from different industries and organisations, who, with an eminently practical approach presented and discussed various aspects of the upcoming regulation and its requirements, possible solutions, examples of use cases, and the obstacles and opportunities for the affected industries and businesses.

The following are the applications of DPP in various sectors as explained at the event:

- Textile industry: It allows consumers to know the origin of the garments, the materials used and the working conditions in the factories.

- Electronics: Facilitates recycling and reuse of components, reducing electronic waste.

- Automotive: It assists in tracking parts and materials, promoting the repair and recycling of vehicles.

- Power supply: It provides information on food traceability, ensuring safety and sustainability in the supply chain.

The impact of the DPP on citizens' lives

But what impact will the use of this kind of novel paradigm have on our daily lives? And how does this impact on us as end users of multiple products and services such as those mentioned above? We will focus on four base cases: informed consumers in any field, ease of product repair, trust and transparency, and efficient recycling.

The DPP provides consumers with access to detailed information about the products they buy, such as their origin, materials and production practices. This allows consumers to make more informed choices and opt for products that are sustainable and ethical. For example, a consumer can choose a garment made from organic materials and produced under fair labour conditions, thus promoting responsible and conscious consumption.

Similarly, one of the great benefits of the DPP is the inclusion of repair guides within the digital passport. This means that consumers can easily access detailed instructions on how to repair a product instead of discarding it when it breaks down. For example, if an appliance stops working, the DPP can provide a step-by-step repair manual, allowing the user to fix it himself or take it to a technician with the necessary information. This not only extends the lifetime of products, but also reduces e-waste and promotes sustainability.

Also, access to detailed and transparent product information through the DPP can increase consumers' trust in brands. Companies that provide a complete and accurate DPP demonstrate their commitment to transparency and accountability, which can enhance their reputation and build customer loyalty. In addition, consumers who have access to this information are better able to make responsible purchasing decisions, thus encouraging more ethical and sustainable consumption habits.

Finally, the DPP facilitates effective recycling by providing clear information on how to break down and reuse the materials in a product. For example, a citizen who wishes to recycle an electronic device can consult the DPP to find out which parts can be recycled and how to separate them properly. This improves the efficiency of the recycling process and ensures that more materials are recovered and reused instead of ending up in landfill, contributing to a circular economy.

Risks and challenges of the DPP

Similarly, as a novel technology and as part of the digital transformation that is taking place in the product sectors, the DPP also presents certain challenges, risks and challenges such as:

- Data Protection: The collection and storage of large amounts of data can put consumers' privacy at risk if not properly managed.

- Security: Digital data is vulnerable to cyber-attacks, which requires robust security measures.

- Interoperability: Standardisation of data across different industries and countries can be complex, making it difficult to implement the DPP on a large scale.

- Costs: Creating and maintaining digital passports can be costly, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Data protection implications

The implementation of the DPP and systems such as CIRPASS implies careful management of personal data. It is essential that companies and digital platforms comply with data protection regulations, such as the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Organisations must ensure that the data collected is used in a transparent manner and with the explicit consent of consumers. In addition, advanced security measures must be implemented to protect the integrity and confidentiality of the data.

Relationship with European Data Spaces

The European Data Spaces are an EU initiative to create a single market for data, promoting innovation and the digital economy. The DPP and CIRPASS are aligned with this vision, as they encourage the exchange of information between different actors in the economy. Data interoperability is essential for the success of the European Data Spaces, and the DPP can contribute significantly to this goal by providing structured and accessible product data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Digital Product Passport and the CIRPASS initiative represent a significant step towards a more circular and sustainable economy. Through the collection and exchange of detailed product data, these systems can improve transparency, encourage responsible consumption practices and reduce environmental impact. However, their implementation requires overcoming challenges related to data protection, security and interoperability. As we move towards a more digitised future, the DPP and CIRPASS have the potential to transform the way we interact with products and contribute to a more sustainable world.

Content prepared by Dr. Fernando Gualo, Professor at UCLM and Data Governance and Quality Consultant The content and the point of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

The European Parliament's tenth parliamentary term started on July, a new institutional cycle that will run from 2024-2029. The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, was elected for a second term, after presenting to the European Parliament her Political Guidelines for the next European Commission 2024-2029.

These guidelines set out the priorities that will guide European policies in the coming years. Among the general objectives, we find that efforts will be invested in:

- Facilitating business and strengthening the single market.

- Decarbonise and reduce energy prices.

- Make research and innovation the engines of the economy.

- Boost productivity through the diffusion of digital technology.

- Invest massively in sustainable competitiveness.

- Closing the skills and manpower gap.

In this article, we will explain point 4, which focuses on combating the insufficient diffusion of digital technologies. Ignorance of the technological possibilities available to citizens limits the capacity to develop new services and business models that are competitive on a global level.

Boosting productivity with the spread of digital technology

The previous mandate was marked by the approval of new regulations aimed at fostering a fair and competitive digital economy through a digital single market, where technology is placed at the service of people. Now is the time to focus on the implementation and enforcement of adopted digital laws.

One of the most recently approved regulations is the Artificial Intelligence (AI) Regulation, a reference framework for the development of any AI system. In this standard, the focus was on ensuring the safety and reliability of artificial intelligence, avoiding bias through various measures including robust data governance.

Now that this framework is in place, it is time to push forward the use of this technology for innovation. To this end, the following aspects will be promoted in this new cycle:

- Artificial intelligence factories. These are open ecosystems that provide an infrastructure for artificial intelligence supercomputing services. In this way, large technological capabilities are made available to start-up companies and research communities.

- Strategy for the use of artificial intelligence. It seeks to boost industrial uses in a variety of sectors, including the provision of public services in areas such as healthcare. Industry and civil society will be involved in the development of this strategy.

- European Research Council on Artificial Intelligence. This body will help pool EU resources, facilitating access to them.

But for these measures to be developed, it is first necessary to ensure access to quality data. This data not only supports the training of AI systems and the development of cutting-edge technology products and services, but also helps informed decision-making and the development of more accurate political and economic strategies. As the document itself states " Access to data is not only a major driver for competitiveness, accounting for almost 4% of EU GDP, but also essential for productivity and societal innovations, from personalised medicine to energy savings”.

To improve access to data for European companies and improve their competitiveness vis-à-vis major global technology players, the European Union is committed to "improving open access to data", while ensuring the strictest data protection.

The European data revolution

"Europe needs a data revolution. This is how blunt the President is about the current situation. Therefore, one of the measures that will be worked on is a new EU Data Strategy. This strategy will build on existing standards. It is expected to build on the existing strategy, whose action lines include the promotion of information exchange through the creation of a single data market where data can flow between countries and economic sectors in the EU.

In this framework, the legislative progress we saw in the last legislature will continue to be very much in evidence:

- Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on open data and re-use of public sector information, which establishes the legal framework for the re-use of public sector information, made available to the public as open data, including the promotion of high-value data.

- Regulation (EU) 2022/868 on European Data Governance (EDG), which regulates the secure and voluntary exchange of data sets held by public bodies over which third party rights concur, as well as data brokering services and the altruistic transfer of data.

- Regulation (EU) 2023/2854 on harmonised rules for fair access to and use of data (Data Act), which promotes harmonised rules on fair access and use of data in the framework of the European Strategy.

The aim is to ensure a "simplified, clear and coherent legal framework for businesses and administrations to share data seamlessly and at scale, while respecting high privacy and security standards".

In addition to stepping up investment in cutting-edge technologies, such as supercomputing, the internet of things and quantum computing, the EU plans to continue promoting access to quality data to help create a sustainable and solvent technological ecosystem capable of competing with large global companies. In this space we will keep you informed of the measures taken to this end.

The European Drug Report provides a current overview of the drug situation in the region, analysing the main trends and emerging threats. It is a valuable publication, with a high number of downloads, which is quoted in many media outlets.

The report is produced annually by the European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA), the current name of the former European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. It collects and analyses data from EU Member States, together with other partner countries such as Turkey and Norway, to provide a comprehensive picture of drug use and supply, drug harms and harm reduction interventions. The report contains comprehensive datasets on these issues disaggregated at the national level, and even, in some cases, at the city level (such as Barcelona or Palma de Mallorca).

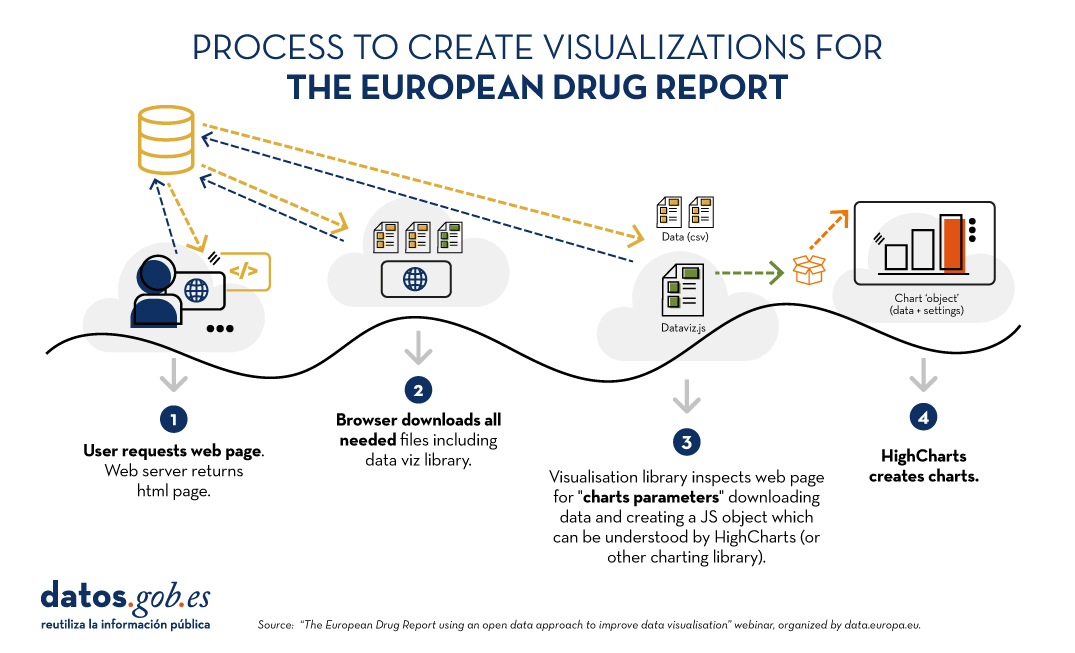

This study has been carried out since 1993 and translated into more than 20 official languages of the European Union. However, in the last two years it has introduced a new feature: a change in internal processes to improve the visualisation of the data obtained. A process they explained in the recent webinar "The European Drug Report: using an open data approach to improve data visualisation", organised by the European Open Data Portal (data.europa.eu) on 25 June. The following is a summary of what the Observatory's representatives had to say at this event.

The need for change

The Observatory has always worked with open data, but there were inefficiencies in the process. Until now, the European Drug Report has always been published in PDF format, with the focus on achieving a visually appealing product. The internal process leading up to the publication of the report consisted of several stages involving various teams:

- A team from the Observatory checked the format of the data received from the supplier and, if necessary, adapted it.

- A specialised data analysis team created visualisations from the data.

- A specialised drafting team drafted the report. The team that had created the visualisations could collaborate in this phase.

- An internal team validated the content of the report.

- The data provider checked that the Observatory had interpreted the data correctly.

Despite the good reception of the report and its format, in 2022 the Observatory decided to completely change the publication format for the following reasons:

- Once the various steps of the publication process had been initiated, the data were formatted and were no longer machine-readable. This reduced the accessibility of the data, e.g. for screen readers, and limited its reusability.

- If errors were detected in the different steps of the process, they were corrected directly on the format of the data in this step. In other words, if an error was detected in a chart during the revision phase, it was corrected directly on that chart. This procedure could cause errors and dull the traceability of data, limiting efficiency: the same static graph could be present several times in the document and each mention had to be corrected individually.

- At the end of the process, the format of the source data had to be adjusted due to changes in the publication procedure.

- Many of the users who consulted the report did so from a mobile device, for which the PDF format was not always suitable.

- Because they are neither accessible nor mobile-friendly, PDF documents did not usually appear as the first result in search engines. This point is important for the Observatory, as many users find the report through search engines.

A responsive web format was needed, which automatically adjusts a website to the size and layout of its users' devices. The aim was to:

- Improved accessibility.

- A more streamlined process for creating visualisations.

- An easier translation process.

- An increase in visitors from search engines.

- Greater modularity.

The process behind the new report

In order to completely transform the publication format of the report, an ad hoc visualisation process has been carried out, summarised in the following image:

Figure 1. Process for creating visualizations for the European Drug Report. Source EN: Webinar “The European Drug Report using an open data approach to improve data visualisation”, organized by data.europa.eu.

The main new feature is that visualisations are created dynamically from the source data. In this way, if something is changed in these data, it is automatically changed in all visualisations that feed on it. Using the Drupal content management system, on which much of the site is based, administrators can register changes that will automatically be reflected in the HTML and therefore in the displays. In addition, site administrators have a visualisation generator which, based on data and indications - equivalent to simple instructions such as "sort from highest to lowest" expressed in HTML - creates visualisations without the need to touch code.

The same dynamic update procedure applies to the PDF that the user can download. If there are changes in the data, in the visualisations or if typographical errors are corrected, the PDF is generated again through a compilation process that the Observatory has created specifically for this task.

The report after the change

The report is currently published in HTML version, with the possibility to download chapters or the full report in PDF format. It is structured by thematic modules and also allows the consultation of annexes.

Furthermore, the data are always published in CSV format and the licensing conditions of the data (CC-BY-4.0) are indicated on the same page. The reference to the source of the data is always made available to the reader on the same page as a visualisation.

With this change in procedure and format, benefits for all have been achieved. From the readers' point of view, the user experience has been improved. For the organisation, the publication process has been streamlined.

In terms of open data, this new approach allows for greater traceability, as the data can be consulted at any time in its current format. Moreover, according to the Observatory speakers, this new format of the report, together with the fact that the data and visualisations are always up-to-date, has increased the accessibility of the data for the media.

You can access the webinar materials here:

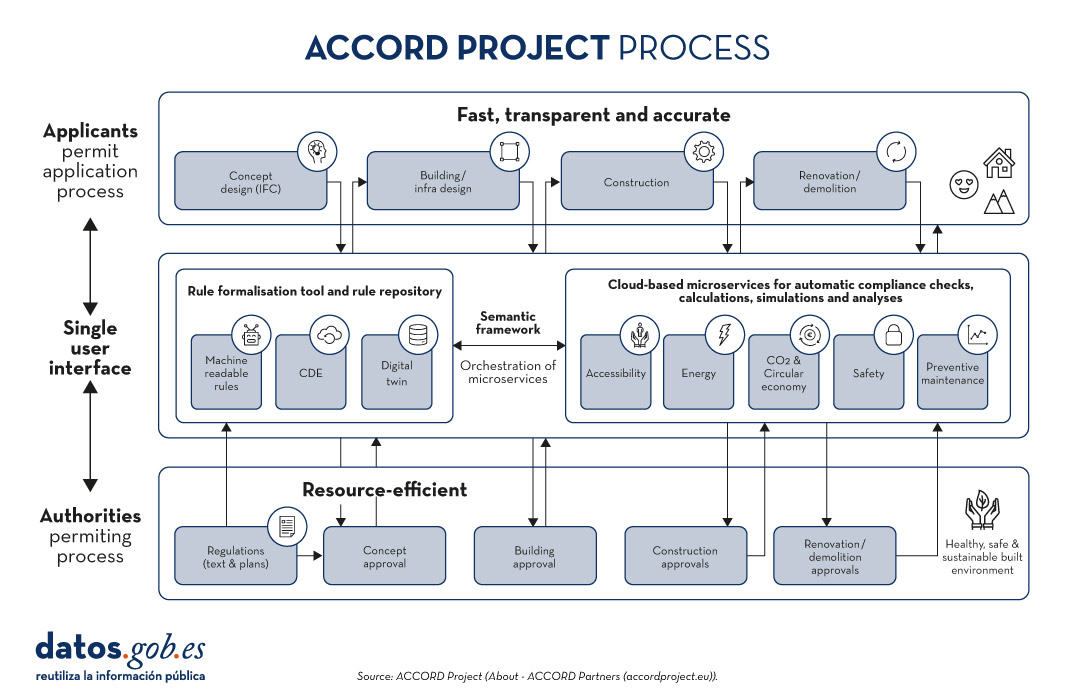

The publication on Friday 12 July 2024 of the Artificial Intelligence Regulation (AIA) opens a new stage in the European and global regulatory framework. The standard is characterised by an attempt to combine two souls. On the one hand, it is about ensuring that technology does not create systemic risks for democracy, the guarantee of our rights and the socio-economic ecosystem as a whole. On the other hand, a targeted approach to product development is sought in order to meet the high standards of reliability, safety and regulatory compliance defined by the European Union.

Scope of application of the standard

The standard allows differentiation between low-and medium-risk systems, high-risk systems and general-purpose AI models. In order to qualify systems, the AIA defines criteria related to the sector regulated by the European Union (Annex I) and defines the content and scope of those systems which by their nature and purpose could generate risks (Annex III). The models are highly dependent on the volume of data, their capacities and operational load.

AIA only affects the latter two cases: high-risk systems and general-purpose AI models. High-risk systems require conformity assessment through notified bodies. These are entities to which evidence is submitted that the development complies with the AIA. In this respect, the models are subject to control formulas by the Commission that ensure the prevention of systemic risks. However, this is a flexible regulatory framework that favours research by relaxing its application in experimental environments, as well as through the deployment of sandboxes for development.

The standard sets out a series of "requirements for high-risk AI systems" (section two of chapter three) which should constitute a reference framework for the development of any system and inspire codes of good practice, technical standards and certification schemes. In this respect, Article 10 on "data and data governance" plays a central role. It provides very precise indications on the design conditions for AI systems, particularly when they involve the processing of personal data or when they are projected on natural persons.

This governance should be considered by those providing the basic infrastructure and/or datasets, managing data spaces or so-called Digital Innovation Hubs, offering support services. In our ecosystem, characterised by a high prevalence of SMEs and/or research teams, data governance is projected on the quality, security and reliability of their actions and results. It is therefore necessary to ensure the values that AIA imposes on training, validation and test datasets in high-risk systems, and, where appropriate, when techniques involving the training of AI models are employed.

These values can be aligned with the principles of Article 5 of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and enrich and complement them. To these are added the risk approach and data protection by design and by default. Relating one to the other is ancertainly interesting exercise.

Ensure the legitimate origin of the data. Loyalty and lawfulness

Alongside the common reference to the value chain associated with data, reference should be made to a 'chain of custody' to ensure the legality of data collection processes. The origin of the data, particularly in the case of personal data, must be lawful, legitimate and its use consistent with the original purpose of its collection. A proper cataloguing of the datasets at source is therefore indispensable to ensure a correct description of their legitimacy and conditions of use.

This is an issue that concerns open data environments, data access bodies and services detailed in the Data Governance Regulation (DGA ) or the European Health Data Space (EHDS) and is sure to inspire future regulations. It is usual to combine external data sources with the information managed by the SME.

Data minimisation, accuracy and purpose limitation

AIA mandates, on the one hand, an assessment of the availability, quantity and adequacy of the required datasets. On the other hand, it requires that the training, validation and test datasets are relevant, sufficiently representative and possess adequate statistical properties. This task is highly relevant to the rights of individuals or groups affected by the system. In addition, they shall, to the greatest extent possible, be error-free and complete in view of their intended purpose. AIA predicates these properties for each dataset individually or for a combination of datasets.

In order to achieve these objectives, it is necessary to ensure that appropriate techniques are deployed:

- Perform appropriate processing operations for data preparation, such as annotation, tagging, cleansing, updating, enrichment and aggregation.

- Make assumptions, in particular with regard to the information that the data are supposed to measure and represent. Or, to put it more colloquially, to define use cases.

- Take into account, to the extent necessary for the intended purpose, the particular characteristics or elements of the specific geographical, contextual, behavioural or functional environment in which the high-risk AI system is intended to be used.

Managing risk: avoiding bias

In the area of data governance, a key role is attributed to the avoidance of bias where it may lead to risks to the health and safety of individuals, adversely affect fundamental rights or give rise to discrimination prohibited by Union law, in particular where data outputs influence incoming information for future operations. To this end, appropriate measures should be taken to detect, prevent and mitigate possible biases identified.

The AIA exceptionally enables the processing of special categories of personal data provided that they offer adequate safeguards in relation to the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons. But it imposes additional conditions:

- the processing of other data, such as synthetic or anonymised data, does not allow effective detection and correction of biases;

- that special categories of personal data are subject to technical limitations concerning the re-use of personal data and to state-of-the-art security and privacy protection measures, including the pseudonymisation;

- that special categories of personal data are subject to measures to ensure that the personal data processed are secured, protected and subject to appropriate safeguards, including strict controls and documentation of access, to prevent misuse and to ensure that only authorised persons have access to such personal data with appropriate confidentiality obligations;

- that special categories of personal data are not transmitted or transferred to third parties and are not otherwise accessible to them;

- that special categories of personal data are deleted once the bias has been corrected or the personal data have reached the end of their retention period, whichever is the earlier;

- that the records of processing activities under Regulations (EU) 2016/679 and (EU) 2018/1725 and Directive (EU) 2016/680 include the reasons why the processing of special categories of personal data was strictly necessary for detecting and correcting bias, and why that purpose could not be achieved by processing other data.

The regulatory provisions are extremely interesting. RGPD, DGA or EHDS are in favour of processing anonymised data. AIA makes an exception in cases where inadequate or low-quality datasets are generated from a bias point of view.

Individual developers, data spaces and intermediary services providing datasets and/or platforms for development must be particularly diligent in defining their security. This provision is consistent with the requirement to have secure processing spaces in EHDS, implies a commitment to certifiable security standards, whether public or private, and advises a re-reading of the seventeenth additional provision on data processing in our Organic Law on Data Protection in the area of pseudonymisation, insofar as it adds ethical and legal guarantees to the strictly technical ones. Furthermore, the need to ensure adequate traceability of uses is underlined. In addition, it will be necessary to include in the register of processing activities a specific mention of this type of use and its justification.

Apply lessons learned from data protection, by design and by default

Article 10 of AIA requires the documentation of relevant design decisions and the identification of relevant data gaps or deficiencies that prevent compliance with AIA and how to address them. In short, it is not enough to ensure data governance, it is also necessary to provide documentary evidence and to maintain a proactive and vigilant attitude throughout the lifecycle of information systems.

These two obligations form the keystone of the system. And its reading should even be much broader in the legal dimension. Lessons learned from the GDPR teach that there is a dual condition for proactive accountability and the guarantee of fundamental rights. The first is intrinsic and material: the deployment of privacy engineering in the service of data protection by design and by default ensures compliance with the GDPR. The second is contextual: the processing of personal data does not take place in a vacuum, but in a broad and complex context regulated by other sectors of the law.

Data governance operates structurally from the foundation to the vault of AI-based information systems. Ensuring that it exists, is adequate and functional is essential. This is the understanding of the Spanish Government's Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2024 which seeks to provide the country with the levers to boost our development.

AIA makes a qualitative leap and underlines the functional approach from which data protection principles should be read by stressing the population dimension. This makes it necessary to rethink the conditions under which the GDPR has been complied with in the European Union. There is an urgent need to move away from template-based models that the consultancy company copies and pastes. It is clear that checklists and standardisation are indispensable. However, its effectiveness is highly dependent on fine tuning. And this calls particularly on the professionals who support the fulfilment of this objective to dedicate their best efforts to give deep meaning to the fulfilment of the Artificial Intelligence Regulation.

You can see a summary of the regulations in the following infographic:

Content prepared by Ricard Martínez, Director of the Chair of Privacy and Digital Transformation. Professor, Department of Constitutional Law, Universitat de València. The contents and points of view reflected in this publication are the sole responsibility of its author.

For some time now we have been hearing about high-value dataset, those datasets whose re-use is associated with considerable benefits for society, the environment and the economy. They were announced in Directive (EU) 2019/1024 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on open data and the re-use of public sector information, and subsequently defined in Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/138 of 21 December 2022 establishing a list of specific high-value datasets and modalities for publication and re-use.

In particular, six categories of dataset are concerned: geospatial, Earth observation and environment, meteorology, statistics, companies and company ownership, and mobility. The detail of these categories and how these datasets should be opened is summarised in the following infographic:

Click on the image or here to expand and access the accessible version

For years, even before the publication of Directive (EU) 2019/1024,Spanish organisations have been working to make this type of datasets available to developers, companies and any citizen who wants to use them, with technical characteristics that facilitate their reuse. However, the Regulation has laid down a number of specific requirements to be met. Below is a summary of the progress made in each category.

Geospatial data

For geospatial data, the implementing regulation (EU) 2023/138 takes into account the categories indicated in Directive 2007/2/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 March 2007 establishing an Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community (INSPIRE), with the exception of agricultural and reference parcels, for which Regulation (EU) 2021/2116 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 2 December 2021applies.

Spain has complied with the INSPIRE Directive for years, thanks to the Law 14/2010 of 5 July 2010 on geographic information infrastructures and services in Spain (LISIGE), which transposes the Directive. Citizens have at their disposal the Official Catalogue of INSPIRE Data and Services of Spain, as well as the catalogues of the Spatial Data Infrastructures of the Autonomous Communities. This has resulted in comprehensive geographical coverage, with exhaustive metadata, which complies with European requirements.

- You can see the dataset currently published by our country in this category on the INSPIRE Geoportal. You can read more about it in this post.

Earth observation and environmental data